The History of New Mexico

Collapse

Expand

-

Chapter 11: Resistance & Resilience in Territorial New Mexico

- Resistance & Resilience in Territorial New Mexico

- Las Gorras Blancas: Millitant Resistance

- Conflict over Language in Schools

- Blackdom: African American Settler Communities

- References & Further Reading

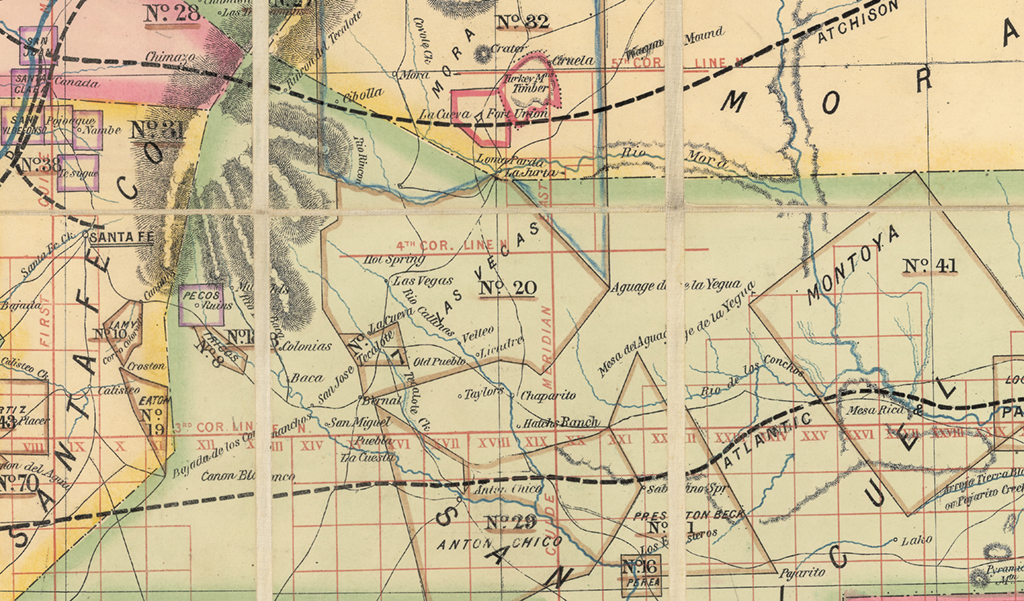

On the heels of railroad development and the arrival of an increasing number of Anglo American migrants from the East, Las Vegas, seat of San Miguel County, rivaled Santa Fe and Albuquerque for the title of the territory’s economic center. As tourists flocked to the Castañeda Hotel and other Fred Harvey Company attractions, speculators also arrived. They hoped to make a fortune by capitalizing on the lands of the Las Vegas Land Grant. In an effort to transfer the communally held land and resources of the grant to private property, they erected barbed wire fences and filed litigation with the Office of the Land Surveyor.

Under the U.S. legal regime, community or corporate land holding held little weight. Time and time again, lawyers and speculators (sometimes one and the same, as in the case of Thomas B. Catron) utilized their knowledge of American jurisprudence to whittle away at the land grants. Despite the guarantees of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, by the late 1880s mercedarios faced an increasingly uphill battle. As San Miguel County gained political, social, and economic prominence in the territory, it also led other counties in terms of stock raising.

Many homesteaders and speculators arrived in San Miguel County with the intention of staking out claims of their own based on the 1862 Homestead Act. Despite the Act’s guarantee of 160 acres to those who settled unimproved lands and remained on them for a period of five years, the unresolved status of the Las Vegas Land Grant complicated matters. As it stood at the time of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the grant included nearly 500,000 acres, and nearly three decades later court cases had yet to resolve its status.

Unwilling to wait for a resolution of its legal boundaries, speculators erected fences, homes, and barns on lands within the grant. Lush grasslands, timber, and a central location amenable to rail connections attracted them to the area. In a dramatic turn of events, in 1887 mercedarios led by the Padilla brothers erected fences of their own in order to protect lands that, from their perspective, should have remained a commons for all land grant heirs. Shortly thereafter, the Las Vegas Land and Cattle Company filed a lawsuit against the Padillas to challenge their claims to communal access to land and resources within the grant.

Courtesy of Nebraska State Historical Society

Chief Justice of the New Mexico Supreme Court, Elisha Long, heard the case, titled Milhiser v. Padilla. The usual suspects were represented in the courtroom: representatives of a powerful American corporation against the heirs of a Mexican land grant. To better understand the issues of the case, Long appointed a special agent to act as an arbitrator. When the arbitrator found Padilla’s actions to be justified, Long failed to act immediately. The case remained in limbo for over a year before Long finally issued a decision in favor of the mercedarios in November of 1889.

The Las Vegas Land Grant case came to a head within the context of systematic political and economic fraud. As a result of the activities of speculators and the machinations of members of the Santa Fe Ring, homesteading protocols were routinely violated in San Miguel County. An 1885 investigation under Democratic Governor Edmund G. Ross, an avowed enemy of the Ring, discovered collusion between the district attorney in San Miguel County, Miguel Salazar, and Max Frost, registrar of the Santa Fe Land Office. With the aid of Salazar and Frost, speculators and cattle ranchers rapidly gained access to the best grazing lands, watering holes, and timber resources. A tax assessment completed in 1890 showed that two small groups of Anglo newcomers controlled about half of San Miguel County’s total cattle operations.

Courtesy of Fray Angélico Chávez History Library

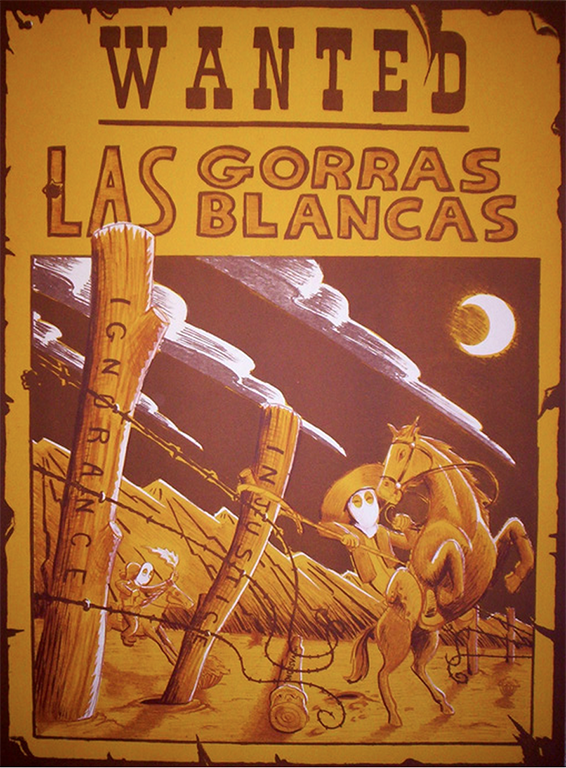

Chief Justice Long’s delay in deciding the Las Vegas Land Grant case created an opportunity for speculators to erect fences and make improvements on plots of land that they claimed as their private property under the provisions of the Homestead Act. In the spring of 1889, in response to unauthorized speculation, Las Gorras Blancas emerged. Riding at night, they cut fences that speculators had erected. Their efforts targeted the markers of dispossession: barbed wire, barns, and railroad ties.

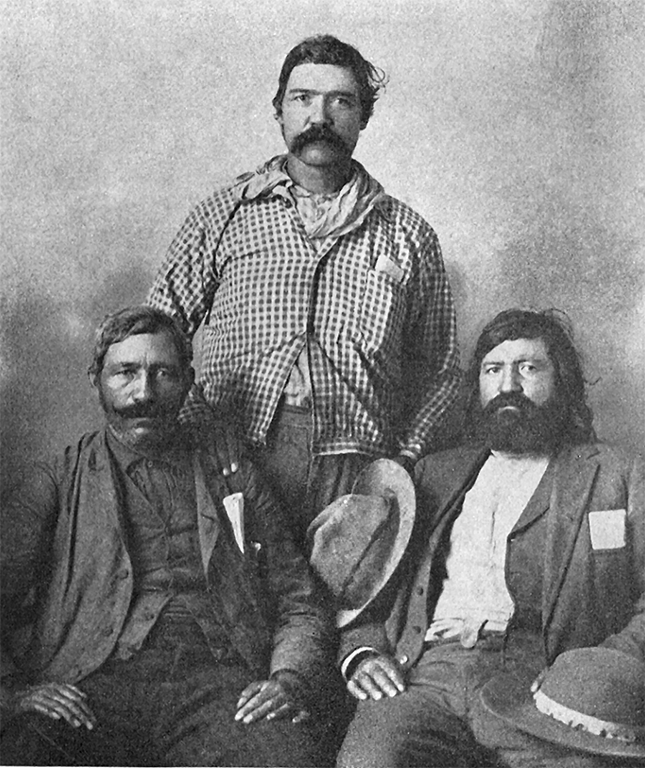

Members of Las Gorras Blancas wore white hoods to protect their identities, taking their cues from previous vigilante White Cap movements that had developed in Indiana and other places in the Midwest. Officials in Santa Fe and Las Vegas believed that Juan José Herrera and his brothers, Pablo and Nicanor, spearheaded the group’s organization in rural communities like El Salitre, El Burro, Ojitos Fríos, and San Gerónimo. Juan José was deeply involved with labor organization in San Miguel County. He had traveled to Utah, Colorado, Wyoming, and Kansas where he began to work in unionization movements. He supported several local chapters of the Knights of Labor which were composed primarily of Spanish-speaking people. Accordingly, those chapters used the Spanish translation of the Union’s name, Caballeros del Trabajo.

Courtesy of Charles A. Siringo

Herrera emphatically denied any involvement with Las Gorras Blancas, although his alleged participation later became a point of pride for members of his family. In an oral history interview late in her life, his daughter Rosa Herrera de McAdams proudly confirmed that Juan José Herrera had, in fact, organized Las Gorras Blancas. Whatever the actual circumstances of the group’s organization, the masked night riders directly addressed the nuevomexicano community’s most pressing problems in San Miguel County.

Near the end of April of 1889, Las Gorras Blancas took their first public action when they uprooted four miles of newly erected fence line that belonged to two British ranchers near San Gerónimo. They not only took the fences down, they reduced the fence posts to splinters and cut barbed wire into small pieces, rendering the material unusable. Additionally, the group targeted rico nuevomexicano and Anglo squatters alike. At San Ignacio, for example, riders relentlessly attacked José Ignacio Luján’s sawmill in June and July of 1889.

Courtesy of Eric J. Garcia

San Miguel County and Santa Fe officials scrambled to investigate the Gorras’ destructive actions, although they were unwilling to address any of the political or land issues that the masked night riders hoped to alleviate. In August, Las Gorras Blancas destroyed miles of fencing and crops that belonged to Sheriff Lorenzo López. Much to the chagrin of local officials, the sheriff bowed to the demand that he remove remaining sections of fence himself. As historian Anselmo Arellano has shown, extended family ties existed between the Herreras and López.1 Their kinship illustrates the practice of compadrazgo and helps to explain López’s compliance with, and later support of, Las Gorras Blancas.

Las Gorras Blancas generally avoided direct attacks on individuals. Their primary targets were the symbols of legal corruption and land dispossession. Yet, in a few cases, their actions nearly resulted in direct physical harm to their targets. In November of 1889, the railroad agent at Rowe determined to prevent the destruction of rail property and he confronted a group of Gorras with a loaded shotgun in hand. The result was a brief gun battle that forced him to flee “into his house to save his life.”2 In another instance, Las Gorras Blancas set the homes of the surveyor general and militia captain ablaze. All narrowly escaped with their lives.

At about the same time that Chief Justice Long issued his decision in the Las Vegas Land Grant case, Los Caballeros del Trabajo and Las Gorras Blancas dominated the political conversation in San Miguel County. In an effort to rein in both groups’ increasing popularity, District Attorney Salazar ramped up efforts to discover and prosecute members of the clandestine organization. Based on thin evidence, Salazar attempted to bring accused members of Las Gorras Blancas to trial. On November 1, 1889, as the date of the first trials neared, a group of sixty-three Gorras surrounded the Las Vegas Courthouse and then journeyed to the jail in a show of solidarity with those who had been imprisoned.

Although figures like Salazar and probate judge Manuel C. de Baca feared open hostilities from Las Gorras Blancas, no attacks materialized. Instead, the jury in the case returned a verdict of not guilty. As historian Anselmo Arellano characterized the case, “the defendants had successfully argued in court that the charges were not related to Gorras Blancas activities; their problem had stemmed from a land dispute.”3 Still, the final day of district court saw twenty-six more indictments against accused Gorras. This time, Juan José and Nicanor Herrera were included in the group that was charged with the destruction of fences.

Perhaps connected to his positive decision for Las Vegas mercedarios, Chief Justice Long reduced bail for the group from $500 to $250. All of those indicted were able to post bond with the support of community members favorable to the activities of Las Gorras Blancas. When district court reconvened in the spring of 1890, all of the defendants presented themselves to honor their bonds. Once again, the Herreras and all others were cleared of any wrongdoing.

In early March of 1890, just prior to the trial, a group of nearly 300 Gorras posted copies of what they called the group’s “Platform and Principles.” The manifesto was quite lengthy, and was distributed in the form of handbills and published in the Las Vegas Optic and La Voz del Pueblo in both English and Spanish. The Gorras made it clear that they did not oppose lawyers or economic development. Nuevomexicanos, Native Americans, and Anglo Americans alike considered modernization to be an unstoppable, and even welcome, force. Instead, Las Gorras Blancas wished to promote the rights of all to access their living from the land. Among the group’s proclamations:

Our purpose is to protect the rights and interests of the people in general; especially those of the helpless classes.

We want the Las Vegas Grant settled to the benefit of all concerned, and this we hold is the entire community within the grant. . . .

We are down on race issues, and will watch race agitators. We are all human brethren, under the same glorious flag.

We favor irrigation enterprises, but will fight any scheme that tends to monopolize the supply of water courses to the detriment of residents living on lands watered by the same streams. . . .

We do not care how much you get so long as you do so fairly and honestly. . . .

Las Gorras Blancas, 1,500 Strong and Growing Daily4

As also indicated in the final section of the declaration, members of Las Gorras Blancas initiated their militant actions as a response to speculators’ and politicians’ efforts to intimidate them into giving up their rights to common land and resource usage.

In repeated shows of solidarity with local communities in San Miguel County, as well as in the Gorras’ political and social agenda, Las Gorras Blancas emerged as a broad social movement that stood in direct opposition to the burgeoning economic and political order. Local power brokers and officials in Santa Fe considered their activities to be a significant threat. Miguel Salazar and Manuel C. de Baca derisively characterized them as “anarchical, revolutionary, and communistic” in communications to Governor L. Bradford Prince.5

The most intense period of fence cutting activities spanned the period between March and November of 1890. No major ranching or land development corporation in San Miguel County escaped the attention of Las Gorras Blancas. In the spring of 1890, the Gorras expanded their activities from fence cutting to the destruction of railroad tracks, telegraph lines, and some buildings. In August, railroad workers arrived at the job to find a notice that read, “you are advised to leave here at once otherwise you will not be able to do so.”6 Attacks on the railroad also included actions that prevented local teamsters from delivering new materials for reconstruction.

As they prohibited them from delivering rails and ties, Las Gorras Blancas also demanded that the teamsters protest for higher wages. To further prevent new rail construction, as well as the further depredation of local timber resources, Gorras posted notices in strategic locations at the edge of forests that advised people to abstain from harvesting trees for lumber or railroad ties unless the price was preapproved by Las Gorras Blancas. The handbills also advised locals against contracting work unless the wages were approved by members of the group. At the bottom, each notice was signed, “White Caps, Fence Cutters, and Death.”7

Support for Las Gorras Blancas remained strong among mercedarios and poorer inhabitants of San Miguel County. The Spanish-language La Voz del Pueblo and the bilingual Las Vegas Daily Optic both declared their support for the group as well. Editor Enrique H. Salazar explained that he relocated La Voz del Pueblo to Las Vegas in order to publish reports in support of nuevomexicanos struggles to maintain their land grants in the face of corrupt dealings. In the summer of 1890, La Voz reported that the accusations against alleged Gorras were clearly unjust because they were dismissed time and again in the courts.

The Las Vegas Daily Optic also issued favorable, although non-incendiary, reports on Las Gorras Blancas. The paper’s editors did not go so far as to condone fence cutting and other destruction, “yet we do not wholly condemn their course.” The editors encouraged residents of San Miguel County to unite to “preserve and protect this great property [the Las Vegas Land Grant] from all further depredation, that it may be kept intact and held for the common benefit of all our citizens.”8

For his part, Governor L. Bradford Prince maintained a cautious approach toward the developments in San Miguel County. He received numerous letters from land speculators and Las Vegas officials that condemned Las Gorras Blancas for committing “outrages” and “depredations” against private property. Prior to his affiliation with the Gorras, Sheriff López requested rifles and ammunition from the governor in order to combat potential violence. His request for weapons from Santa Fe was one of many.

Secretary of the Interior James Noble also pressured Prince to “enforce private rights” as Las Gorras Blancas increased their activities in 1890.9 In turn, members of the U.S. Congress and Benjamin F. Butler, a Washington, D.C., lawyer who owned land in New Mexico, constantly lobbied Noble to take some sort of action. Butler hired his own agent to investigate the situation in San Miguel County, and he made his appeals for the suppression of Las Gorras Blancas based on what scholar David Correia has characterized as “racialized arguments to suggest that only labor agitators could be responsible for the campaign.” Butler advised Noble to remember “that these are Mexicans; that the Mexicans in New Mexico, with the exception of perhaps five per cent, are the most ignorant people on the face of the earth.”10

The governor received just as many letters in favor of Las Gorras Blancas. Many residents of San Miguel County reported that the real root of the problem were the large-scale ranching enterprises that encroached on communal lands, timber, and water. Several correspondents told Governor Prince that ranchers prevented mercedarios and others from gaining access to grazing lands and water sources that family members had used for generations. Even the district judge who dismissed charges against accused Gorras reported that unrest was due to dispossession of lands and resources by large ranching interests. Based on such reports, Prince concluded that “there is much exaggeration about the matter and that every kind of wrongdoing however committed is now very naturally attributed to the so-called White Caps.”11

Perceived ties between Las Gorras Blancas, Los Caballeros del Trabajo, and a new third political party, El Partido del Pueblo Unido (the United People’s Party), also served to bring the situation in San Miguel County to national attention. Juan José Herrera vigorously promoted Los Caballeros del Trabajo to help poor farmers and ranchers, many of whom were partidarios (recipients of partido arrangements) or wage laborers on the lands of others. Nuevomexicano members of Los Caballeros tended to stand behind Las Gorras Blancas, but the national-level Knights of Labor and local Anglo-dominated chapters did not. To resolve the conflict between chapters, Herrera met with national union leaders and reiterated his claim that Los Caballeros del Trabajo and Las Gorras Blancas were in no way connected.

As tensions between the local chapters and the national Knights of Labor continued, Los Caballeros del Trabajo maintained a high political profile in Las Vegas. For the July 4 celebrations in 1890, Los Caballeros prepared a series of processions, speeches, and other festivities. On the night of July 3, about 1,000 men on horseback paraded through town to celebrate vespers. The next day, the horsemen once again rode through town, this time led by Sheriff López. The riders and others carried banners and slogans in Spanish that declared their goals as members of the organization. Among the messages on the banners: “Free schools for our children,” “He who touches one of us answers to all,” and “We seek protection for the worker against the monopolist.”12

Among the speakers at the Old Town Plaza that day were Nestor Montoya, a Caballero and editor of La Voz del Pueblo. Mayor Edward Henry from Las Vegas’ New Town also offered a speech in which he commended the Caballeros’ successful organization campaigns. Juan José, Pablo, and Nicanor Herrera led a group of speakers that explained the mission and goals of the organization, and Governor Prince also made a short speech to mark the occasion.

Following the July 4 celebrations, the rising prominence of the Caballeros and the increasing activities of Las Gorras Blancas seemed to have a positive correlation. Increasing pressure from all sides led Governor Prince to personally investigate charges levied against the Gorras in August 1890. Again, a group of Caballeros, led by Nestor Montoya, asserted the claim that their organization was in no way associated with the fence cutters. Following his inquiries, Prince concluded that at least half of the county supported Las Gorras Blancas and he issued a proclamation that warned all guilty parties to cease and desist the destruction of property.

In many ways the governor’s words only fanned the flames of conflict. An editorial in La Voz del Pueblo, for example, argued that Prince should have also issued a proclamation against illegal land and resource speculation. At his behest, county commissioners initiated their own efforts to bring community members together to resolve the conflict. An open meeting led by the district judge only seemed to promote the idea that efforts to find a solution were decidedly one-sided. A large group of those present at the meeting abruptly left in a rage when the judge appointed a committee to create a plan to resolve land and resource disputes. Many of the townspeople believed that the committee should have been elected rather than appointed.

Leaders of Los Caballeros del Trabajo also tried to resolve their estrangement from the Knights of Labor by sending a lengthy letter to the organization’s national leader, Terence V. Powderly. In addition to repeated assurances that local chapters were not affiliated with Las Gorras Blancas, the letter laid out the reasons for which Caballeros opposed the actions of men like Thomas B. Catron and Benjamin F. Butler. The authors of the message characterized them as architects of political and economic intrigues that dispossessed laborers.

Their message was offset by letters that English-speaking Knights of Labor from San Miguel County also sent to Powderly. In racialized terms, they made the case that “ignorant Mexicans” fomented violence and destruction in the county. By August of 1890 even the Las Vegas Daily Optic, often sympathetic to mercedarios’ claims, levied the same types of racialized charges against Las Gorras Blancas.

The clandestine activities of Las Gorras Blancas decreased markedly by the late fall of 1890 as figures like Juan José Herrera focused their attention on expanding the Partido del Pueblo Unido, a third party connected to the rise of the Populist Party in the Midwest. Because Herrera’s work with the Partido coincided with the end of Las Gorras Blancas, the idea that he was behind the clandestine group gained further credence. As Correia points out, however, “by the fall of 1890 every single fence that had enclosed the Las Vegas Land Grant had been cut, and none had survived reconstruction.”13 Perhaps Las Gorras Blancas had simply completed their work by that time.

In November 1890, Partido del Pueblo Unido candidates made a strong showing at the ballot box in San Miguel County. Their entire ticket won election to territorial- and county-level posts. As the new year dawned in 1891, it seemed that the activities of Las Gorras Blancas had translated into an effective political movement.

By February 1891, however, the Partido del Pueblo Unido suffered serious setbacks that prevented the realization of lasting political change. As the first territorial legislative session came to a close that month, Pablo Herrera resigned from the territorial legislature and the party itself. After one session in Santa Fe, he reported that “there is more honesty in the halls of the Territorial prison than in the halls of the legislature.”14 He returned to San Miguel County to resume his labor organization efforts, but territorial officials feared that his work might lead to the resurgence of Las Gorras Blancas. Shortly after he returned to Las Vegas, a sheriff’s deputy shot him down as he walked unarmed down the street in front of the courthouse. The deputy was never indicted.

Not long thereafter, unidentified shooters targeted the offices of Thomas B. Catron. Governor Prince responded by hiring Pinkerton detectives to investigate the Partido del Pueblo and Los Caballeros del Trabajo. Detective Charles Siringo made his sensationalized findings public knowledge, much to the governor’s chagrin. Siringo claimed to have infiltrated the ranks of Las Gorras Blancas, forged a friendship with Nicanor Herrera, and located evidence that Las Gorras Blancas, Los Caballeros del Trabajo, and the Partido del Pueblo Unido were actually closely tied together. His stories created a strong reaction against the Partido, but Prince refused to take legal action due to Siringo’s flimsy evidence.

The United Protection Association in San Miguel County succeeded in dismantling resistance efforts at all levels, however. In print and on the street its members, which included prominent merchants and ranchers, denounced anyone that spoke against commercial interests. The territorial press picked up on their activities, and by the mid-1890s barbed wire fences once again marked off the commons of the Las Vegas Land Grant.

Despite such setbacks, mercedarios and other poor nuevomexicanos in San Miguel County maintained their political activism. Former Sheriff Lorenzo López gained the title “el amo de los pobres” (“the overseer of the poor”) due to his generosity and support of the county’s poorer classes. Félix Martínez, who purchased La Voz del Pueblo, continued to promote the Partido del Pueblo Unido and he won election to the territorial legislature on the third-party ticket in 1892. Resistance and an appeal to the political system thus remained an essential part of nuevomexicano efforts to maintain the commons in San Miguel County.