The History of New Mexico

Collapse

Expand

-

Chapter 11: Resistance & Resilience in Territorial New Mexico

- Resistance & Resilience in Territorial New Mexico

- Las Gorras Blancas: Millitant Resistance

- Conflict over Language in Schools

- Blackdom: African American Settler Communities

- References & Further Reading

One of the primary concerns of the supporters of groups like Los Caballeros del Labor was the education of their children. Among the banners held up at the July 4 procession in Las Vegas was one that read, “Free schools for our children.” Although researchers have translated slogans such as this one into English, we must remember that the actual signs held up that day contained messages in Spanish.

Despite claims made by opponents of statehood and proponents of English-only policies, nuevomexicanos considered the education of their children one of the most important issues of the late nineteenth century. The same was true of Pueblo and Navajo parents. In striking contrast to the situation for Anglo Americans during the same time frame, New Mexican parents faced the troubling question of whether or not compulsory education programs would challenge, and even possibly destroy, their cultural traditions. Language was a central component of indigenous and nuevomexicano cultures.

One of the legacies of New Mexico’s multiple periods of colonialism is that indigenous peoples were continuously left out of important political and social deliberations. Public debates about what languages would be allowed for use in New Mexico’s schools focused on Spanish and English. Many Navajos and Pueblos spoke either English or Spanish by the late nineteenth century. Yet they also continued to preserve their own languages as a means of maintaining their cultural identities in the face of colonization efforts that had been at play in one form or another for almost three centuries.

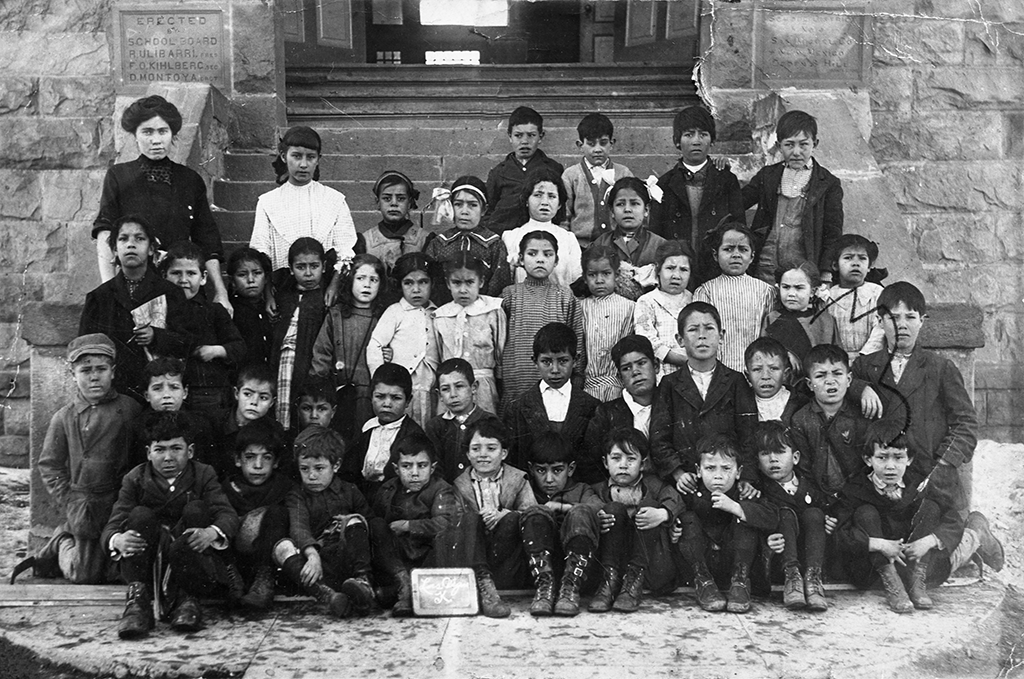

Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 070248

Following the intense violence and devastation of the Long Walk, English language education became a controversial subject among Navajos. The Treaty of 1868 included provisions for compulsory education for their children. Despite the support of some headmen, such as Manuelito, most Navajos ignored the sections of the treaty dealing with education. Based on his commitment to education in the English language and reluctant embrace of Anglo-American ideals, Manuelito sent all three of his sons to the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania. Tragically, all three of them died in connection to their travels to and from the school.

In fact, the longer that boarding schools for native children operated, Navajos became more and more resistant to their methods of eradicating Diné traditions in favor of assimilation into Anglo American modes of thinking. During the 1925 academic year, for example, only 35% of Navajo children were enrolled in school. The percentage further declined by 1948 when just 25% of eligible students enrolled in classes.

Pueblo children were also targets of efforts to place them in boarding schools by the late-nineteenth century. In contrast to the great distances traveled by Navajo children to reach boarding schools far from their family homes in the Dinétah, however, Pueblo students generally attended schools that were much closer to home. Several schools were established on Pueblo lands, such as the one at Santa Clara Pueblo, and the Albuquerque and Santa Fe Indian Schools were relatively close to New Mexico’s nineteen Pueblo communities.

W.H. Cobb (Photographer). Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 136390

Despite the relative advantages offered by proximity and close-knit communities, Pueblo students still faced efforts to eradicate their cultural traditions in the Indian Schools. As historian Margaret Connell Szasz has argued, the experiences of Native American children in boarding school settings were strikingly similar across time and space. The case of a five-year-old San Juan Pueblo girl is illustrative of the humiliation that most students endured. On her first day at the Santa Fe Indian School, the principal indicated a clock on the wall and asked her to tell other students the time. As she recounted, “I just looked at it and I didn’t know what to say. I didn’t know how to tell time, so I just covered my face [with my shawl] and the students laughed.”15

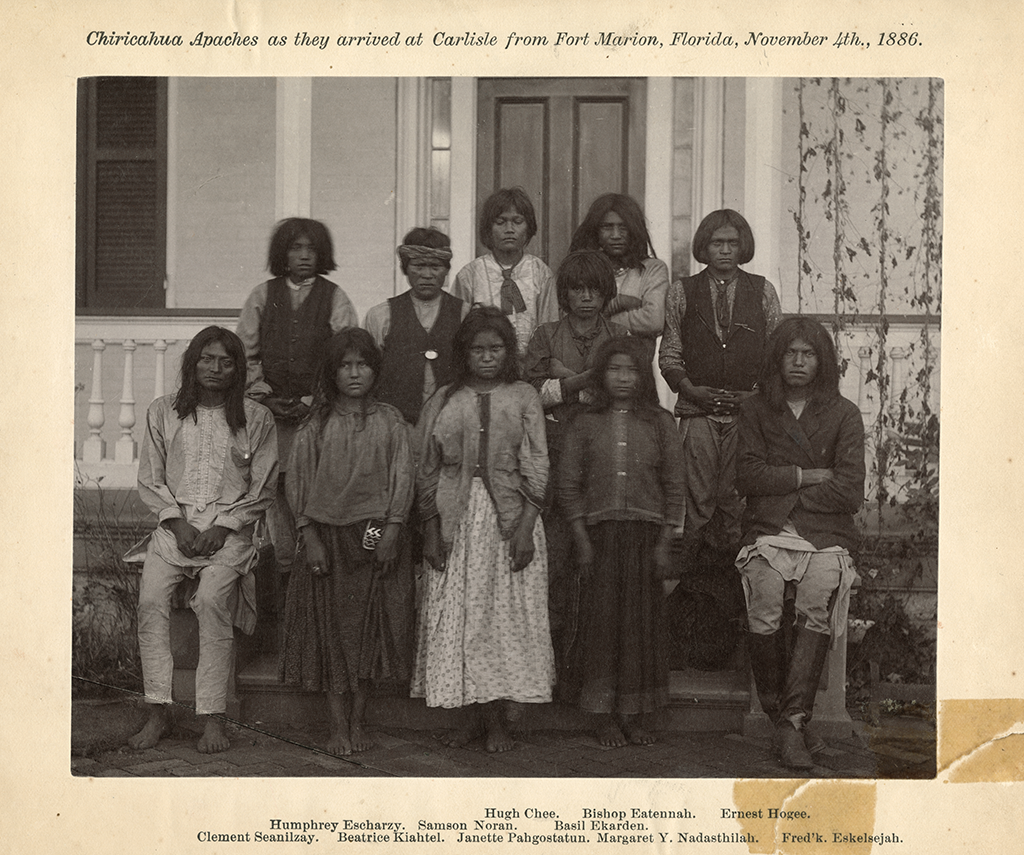

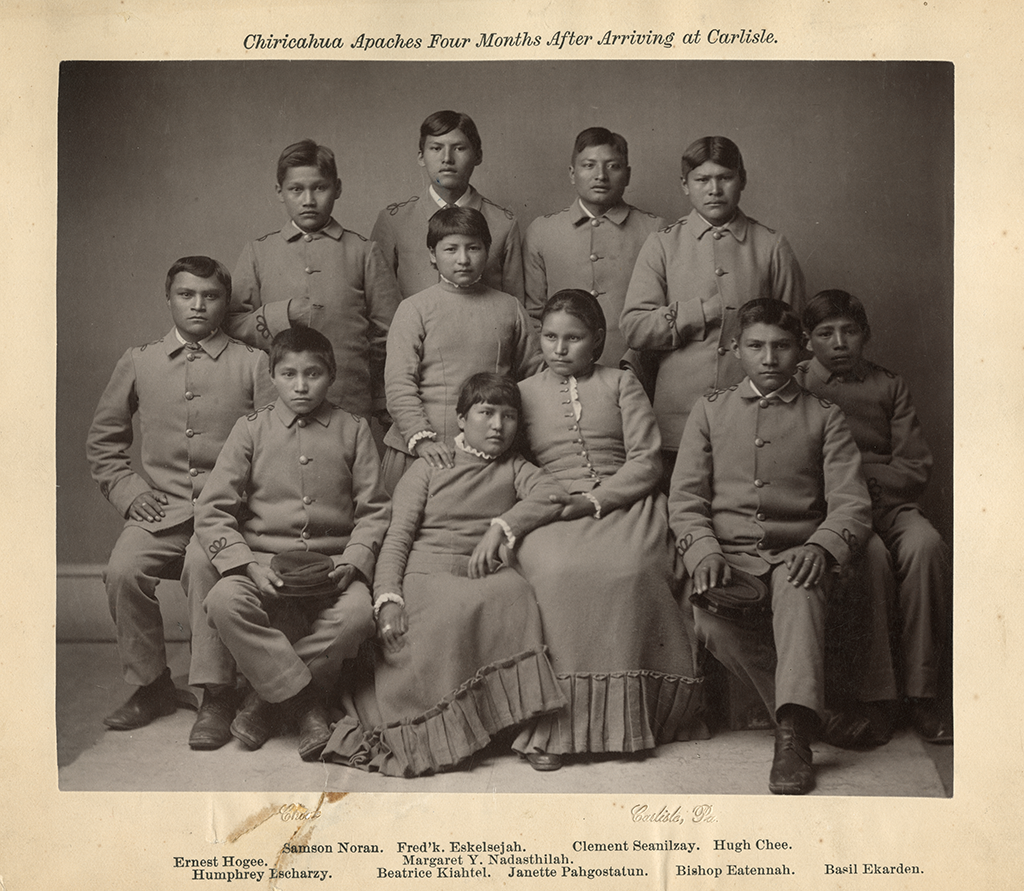

J.H. Choate (Photographer). Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 002113

The methods of cultural assimilation employed at boarding schools have been widely documented. As Captain Richard H. Pratt, founder of the infamous Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, stated, the goal of boarding schools was to “kill the Indian and save the man.” Pratt meant that indigenous peoples should assimilate to white American ways of dressing, speaking, thinking, and acting. In so doing, they were to completely set aside their former traditions, ideals, and languages. Boarding schools were intended as workshops of assimilation.

For young native students, life at boarding schools was a traumatizing experience. Mortification, such as that experienced by the young San Juan Pueblo girl, stemmed not only from ignorance of white American ways of doing things. Pueblo children were forced to cut their long hair, dress in modern styles of clothing worn by white children, answer to new names, and, at times, to participate in drills reminiscent of military routines. They were expressly forbidden to speak their native languages, typically at the risk of corporal punishment.

J.H. Choate (Photographer). Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 002112

As adults, many of those who had attended boarding schools worked tirelessly to bring better educational facilities to their home communities on their various reservations. Suzy Marmon of Laguna Pueblo, for example, attended both the Menaul School in Albuquerque (where her indigenous name was changed to Suzy) and Carlisle. After completing her education in the boarding school system, she worked as a teacher at Isleta Pueblo and then in her own community, “because I felt it was my duty to help my people if I could.”16

Although the schools’ assimilation project was never fully realized, boarding schools had an impact on indigenous languages. The use of Pueblo and Navajo languages was not an option in school settings, and many former students failed to pass along their knowledge of their native language to their children. The eradication of indigenous languages was never up for public debate, in contrast with the use of Spanish in educational settings. Spanish-language usage in New Mexican schools was a point of contention in the years leading up to and following the turn of the twentieth century. The drive to protect the use of Spanish in primary education united nuevomexicanos that had opposed one another in the struggle for social and economic justice led by Las Gorras Blancas, Los Caballeros del Trabajo, and el Partido del Pueblo Unido.

Manuel C. de Baca, who had vehemently opposed the activities of Las Gorras Blancas in his capacity as probate judge, used his position as a member of the territorial Public Education department in the later 1890s to advocate for Spanish in the schools. Amado Chaves led the charge as Superintendent of Public Education in the same time frame. Both men publicly argued against the prevalent notion among Anglo Americans that their use of Spanish made nuevomexicanos unfit for American citizenship.

The pair framed their arguments in two different ways. First, they focused on the beauty of Spanish speech and prose. According to Chaves, Spanish was a “highly important, interesting and sonorous language, and that our territorial institutions should require their graduates to attend a complete course of the same.”17 Much of the Spanish-language press throughout New Mexico supported his arguments with their regular installments of poetry and stories that reflected the elegance of Spanish prose and also helped to preserve local histories and folklore.

Charles F. Lummis (Photographer). Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 065718

Second, proponents of Spanish-language education defended the use of their native tongue based on its functional value. As Chaves also noted, “it is a crime against nature and humanity to try and rob the children of New Mexico of this right, their natural advantage, of the language which is theirs by birthright, to deprive them unjustly of the advantages, great and numerous, which those have who command two languages.”18

When C. de Baca followed up on the utilitarian line of reasoning in the 1899 Territorial Superintendent’s Annual Report, it became clear that claims about the usefulness of Spanish had become more prominent than those focused on its inherent beauty. C. de Baca refuted claims that Spanish usage disqualified nuevomexicanos from citizenship with the idea that New Mexico was unique due to the necessity of bilingualism. He asserted that, “the arguments and declamations of theorists concerning the patriotism manifested by an exclusive use of the English language have little weight when placed beside the fact that a busy world is making an urgent and increasing demand for more young men and young women competent to use fluently both English and Spanish.”19

During the first decade of the twentieth century, the office of Territorial Superintendent of Public Education was filled by an Anglo American, Hiram Hadley, rather than a nuevomexicano. The department’s focus was decidedly different, illustrating the reality that the battle for language usage in the classroom was drawn along ethnic lines. Hadley and his supporters deemphasized the validity of the Spanish language for New Mexican students and offered a line of reasoning paralleling the Progressive Era school of thought. By 1907, Hadley’s education department issued a statement that explicitly stated the importance of training all students in English to help nuevomexicano students discontinue their reliance on Spanish.

In 1910, when the Enabling Act for New Mexico’s statehood finally passed through Congress, the issue of language in the classroom became even more contentious. In the end, through creative writing of the state constitution and careful readings of national-level legislation, nuevomexicano politicians ensured the presence of Spanish in the new state’s primary classrooms. It bears repeating that the concerns of Pueblo and Navajo parents for the preservation of their own languages and traditions were not considered at either the territorial (then state after 1912) or national levels.

Although most New Mexicans were willing to accept almost any terms in order to finally gain statehood by 1910, Article 21 of the Enabling Act was particularly onerous to Spanish-speaking residents. It read: “[the] ability to read, write, speak, and understand English sufficiently without the aid of an interpreter shall be a necessary qualification for all State officers and members of the State legislature.”20 The article did not preclude Spanish in the classroom, but it did threaten to limit political participation to only those who spoke English.

As was so often the case in this time period, the Spanish-language press immediately responded, publishing articles and opinion pieces that refuted the logic of Article 21. As Aurora Lucero wrote in the Santa Fe Daily New Mexican, the idea held by most Anglo Americans in Congress was that nuevomexicanos’ continued use of Spanish illustrated that they were ill-prepared for citizenship. On the contrary, she argued, “the Spanish-Americans of New Mexico have never been bad citizens. They have more than once proved their loyalty to the government and their love for the ‘Stars and Stripes,’ as their conduct in the Civil and Spanish-American wars, and in many of the Indian wars, abundantly testifies.”21

Those involved in the drafting of the state constitution struck out the offensive clause contained in Article 21, “in what was no less than a coup against the national mandate,” according to historian Erlinda Gonzales-Berry.22 In its place, they inserted a provision that called for the use of both Spanish and English in the state legislature and in the publication of legal notices. In this regard, nuevomexicano legislators scored a victory. Their article was in effect for twenty years, then renewed in 1931 and again in 1943. Eventually, the provision dropped from the state constitution because the English language became so pervasive by the mid-twentieth century.

The legislature also protected the voting rights of nuevomexicanos who spoke Spanish as their primary language. Hearkening back to the promises of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, they asserted that nuevomexicanos had been guaranteed full citizenship rights in the U.S. nation—a provision that included the right to vote.

Despite such assertions, New Mexican lawmakers gave in to the demands of the U.S. Congress on the specific point of which language would be used in primary education. In so doing, however, they drafted vague legislation akin to the final wording of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. In creating a relatively vague education provision, nuevomexicano lawmakers “meant to create a space, albeit an ambiguous one, for the inclusion of Spanish in the classroom[.]”23 They understood the harsh reality that many Eastern politicians would not support New Mexico’s statehood unless the English-only educational statue remained in place.

By creating room for the continuance of Spanish in the classroom, nuevomexicano legislators refused to capitulate in the face of political pressure. They did not want to do anything that might prevent statehood—especially after Congress had approved an Enabling Act for the first time—so they had few other options besides political slight-of-hand. In Article 12, section 8, of New Mexico’s state constitution, ambiguous language allowed for Spanish-language instruction in classrooms where the texts were written in English. That article read:

The legislature shall provide for the training of teachers in the normal schools or otherwise so that they may become proficient in both the English and Spanish languages to qualify them to teach Spanish speaking pupils and students in the public schools and educational institutions of the State, and shall provide proper means and methods to facilitate the teaching of the English language and other branches of learning to such pupils and students.

As New Mexico achieved statehood in 1912, Americans were preoccupied to at least some extent with the acquisition of the Panama Canal. Due to the economic importance of the canal, some Eastern-U.S. lawmakers echoed earlier nuevomexicano arguments about the utility of the Spanish language. Some argued that Spanish should be studied by U.S. students in order to prepare them for business relations with Latin American nations afforded by the canal.

Acceptance of Spanish as a subject for primary education was highly conditional. Congressmen made a strong distinction between the idea of native-English speakers taking classes in Spanish and native-Spanish speakers continuing to receive instruction in their native language. The result was the continued categorization of Spanish as a foreign language.

The debate over Spanish language instruction in New Mexico’s classrooms sheds light on the struggle for statehood (the subject of the next chapter) and the inclination of some nuevomexicanos to resist assimilation impulses. Elites who adopted the Spanish-American Ethnic Identity argued that Spanish was on par with English due to its roots as a language of European conquerors. Poorer nuevomexicanos also benefitted from such claims because their children were also able to receive instruction in Spanish in their classrooms.

Although the provision that struck Article 21 from the Enabling Act ceased to be part of the state constitution after the 1940s, scholars and other residents of New Mexico continue to hold it up as evidence of the state’s genesis as a bilingual entity. Despite the important gains achieved through the push for Spanish-language instruction in New Mexico’s schools, deeper issues of colonialism and poverty were not addressed. Most nuevomexicanos remained impoverished and the cultural legacies of indigenous peoples were given no attention at the political and legal levels. Anglo politicians viewed Spanish-speaking New Mexicans as inferior to themselves, while those who spoke Spanish continued to tout their superiority to indigenous peoples. Such was—and is—an unfortunate consequence of New Mexico’s legacy of multiple conquests.