Although many portrayals of the early period of European conquest and colonization have been characterized as dichotomous contests between Spaniards and indigenous peoples, such was never strictly the case. Spaniards consistently relied upon indios amigos to achieve their goals and to build an American empire. Native peoples also became quite adept at playing different groups of Europeans against one another. For example, they noticed competition between French, British, and Spanish colonists in North America, and they used existing political divisions to their advantage. Similarly, natives recognized that Spanish bureaucrats, including governors and judges; clergymen, including Franciscan, Dominican, and Jesuit friars; and encomenderos were often at odds with one another. They astutely played one antagonistic faction against the other in order to improve their own situations.

Spanish conquistadores located and conquered the largest and wealthiest native civilizations in the early part of the sixteenth century. Because the Aztec and Inca Empires employed administrative systems that the Spaniards were able to relate to, they found the task of subduing such peoples to be relatively easy. This is not to say, of course, that there was not resistance to colonialism in those places. Indigenous peoples opposed Spanish attempts to stamp out their cultures and traditions no matter what type of lifeways they practiced. Some people from the Valley of Mexico and the province of Nueva Galicia, for example, joined the Coronado entrada in 1539 for the purpose of escaping to a land far to the north that lay beyond the control of European empires. Yet the fact remained that Spanish administrators preferred sedentary peoples with extensive bureaucratic establishments because such customs and practices were more legible to them. Nomadic groups beyond the Aztec frontier (or the territory formerly controlled by the Aztec Empire), on the other hand, were far more difficult to subdue. In most ways, the total colonization of indigenous peoples never came to fruition.

Cortés’ dreams of power and glory were shattered when the Spanish Crown appointed a viceroy from outside of the colony to rule the province of New Spain. In order to administer an empire that was far removed from (and far larger than) the mother country, Spanish kings created a system of overlapping jurisdictions to ensure the loyalty of their subjects. Since the king could not be present in his imperial holdings, it was in his best interests to ensure that ambitious figures like Cortés had checks on their authority. The viceroyalty of New Spain also included an audiencia (or judicial body), and a bishopric by the mid-1520s. The head of the audiencia often officiated over matters that were also the purview of the viceroy and the bishop. All three leaders might be in agreement about major decision, but more often they opposed each other in attempts to enhance their individual authority through appeals to the king himself. Despite the inefficiency of this type of system, the Spanish crown favored it because it required each leader to seek the approval of the king rather than going off on his (and such leaders were always male) own to challenge imperial control. Beltran Nuño de Guzmán, for example, challenged Cortés’ leadership early on in an attempt to garner the favor of the king. Much to the dismay of both men, the king replaced them with Antonio de Mendoza, the first viceroy of New Spain.

On the heels of the reports and rumors generated by Cabeza de Vaca and his companions’ harrowing experiences (recounted at the beginning of this chapter), many European residents of New Spain imagined the existence of another Aztec Empire in the far north. As the stories were told and retold, they were conflated with existing Spanish legends. By the time that Viceroy Mendoza commissioned Fray Marcos de Niza to lead a reconnaissance mission to the far north, the Spaniards believed that they would there find the Seven Cities of Cíbola. Their imaginations were stoked by legends that had originated during the Iberian reconquest. As early as the eighth century, the tale of the Seven Cities of the Antilles began to circulate. According to the legend, seven (or in some cases eight) Catholic bishops had escaped the Islamic conquest and fled to the Antilles with great wealth. Such legends perpetuated belief in European superiority because they assumed that if advanced societies existed in the world, they were the product of European-descended peoples.

Seven Cities of Cíbola

Native peoples consistently fed the Europeans’ desire to locate mythical cities of wealth. They may have misunderstood the types of items upon which Spaniards placed value because their own notions of ownership and wealth tended to be quite different from those of the explorers. More likely, however, indigenous peoples realized the ease with which they could send entire expeditions away from their homes and families. By the mid-1500s, as we will see in the case of the Coronado entrada, sending Spaniards on wild goose chases for wealth took on added risks of retributive violence. Yet even in the instances that Spaniards came up empty-handed, they never lost the hope that somewhere in the unknown interior of the continent, cities of grandeur did, in fact, exist.

Once Cabeza de Vaca and his three companions returned to Mexico City in the summer of 1536, it did not take long for rumors to circulate of a wondrous land in the far north. Viceroy Mendoza refused to be caught up in the wave of excitement. He lodged the four men in his own home and spent the better part of two months conversing with them about their experiences during their long foray across the deserts of present-day northern Mexico. Although the stories that they reported were highly provocative, they were based on hearsay and the existence of a single copper bell that the survivors had acquired through trade.

After much deliberation, Mendoza concluded that Cabeza de Vaca was “a person who should be relied upon,” and he initiated efforts to organize a reconnaissance party to investigate the rumors.9 Despite his caution, Mendoza wanted to act before other ambitious men undertook their own expeditions to the north. Potential competitors included Hernán Cortés and Beltrán Nuño de Guzmán, both of whom had spoken with Cabeza de Vaca and the others. Cabeza de Vaca himself balked at the proposition of leading the viceroy’s fact-finding mission. He had his own status in mind, asserting the idea that were he to engage in such a journey, he would require a royal appointment on par with that of Mendoza himself. He did not want to subordinate himself and potentially achieve glory for someone else at his own expense. Concerns for the well-being of the indigenous peoples that he encountered also crossed his mind. By not lending his support to Mendoza, he would not be responsible for the death and destruction that he thought would surely accompany the expedition.

In October of 1536, Cabeza de Vaca and Andrés Dorantes de Carranza set sail for Spain in an effort to curry favor through personal reports to the king himself. To ensure that someone with knowledge of the far north remained in New Spain, Mendoza purchased Esteban from Dorantes de Carranza. Esteban thus remained the only survivor “willing” to retrace the steps of their journeys.

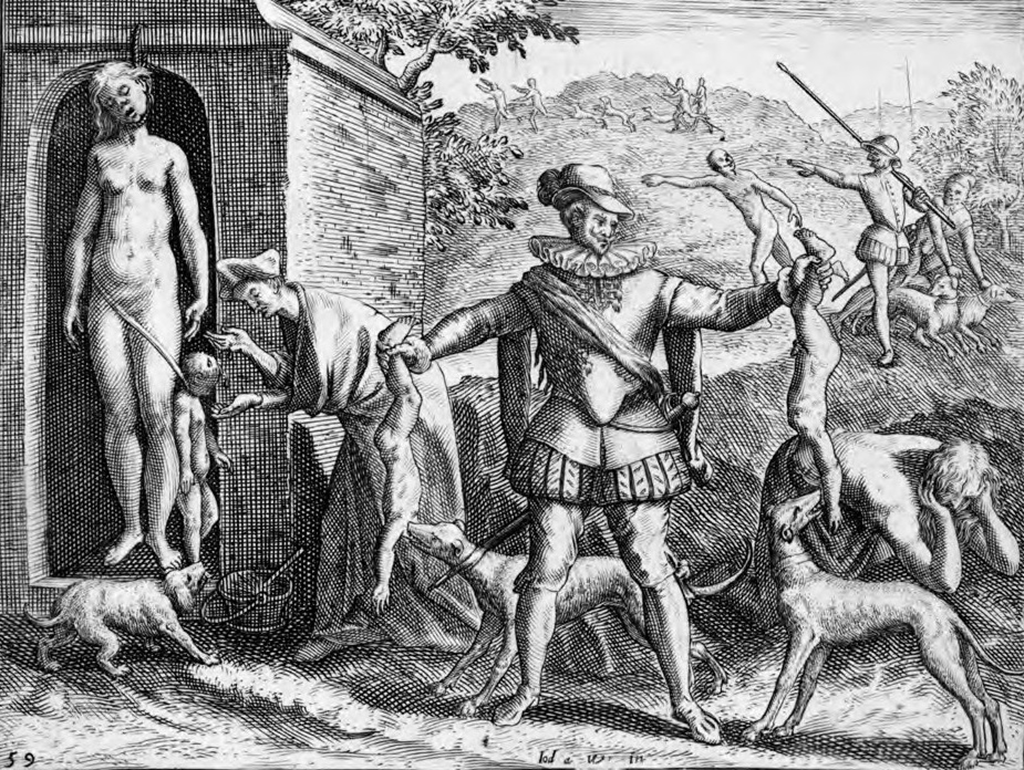

A slave, however, could not lead a royal mission. In order to find an acceptable alternate, Mendoza turned to the leadership of the Franciscan order in Mexico City. Franciscan missionaries had accompanied Cortés on his first mission to the Valley of Mexico, and they had established themselves as the ecclesiastical authorities in the young colony. Additionally, the efforts of two friars, Antonio de Montesinos and Bartolomé de las Casas, to refine royal policies regarding indigenous peoples were gaining traction in royal circles by the late 1530s. Las Casas had been an encomendero prior to his entry into the Dominican order. He and Montesinos wrote volumes on the types of violent abuse that the colonizers enacted against native peoples. Las Casas’ writings, in particular, conjured up images of constant blood baths and sadistic actions on the part of the Spaniards. Unwittingly, his work gave rise to the infamous Black Legend, which painted Spanish conquistadores as intensely violent. Many of the cases of which he wrote were based on rumor and hearsay, but the message that indigenous peoples needed royal protection did not go unheeded.

By 1542 King Carlos I issued a package of legislation known collectively as the “New Laws of the Indies for the Good Treatment and Preservation of the Indians” (or simply as the “New Laws”). The idea was to set a different tone for Spanish expansion in which religious orders were to play a more prominent role. Officials hoped that the participation of priests in new colonization ventures would curb the violence, but not all friars were of the same mindset as Las Casas or Montesinos. In New Spain, Franciscan prominence meant that missionaries would take the lead in keeping settlers and explorers in check. Missionaries, despite their general inclination to stand up for indigenous peoples’ right to live free of Spanish violence, had the goal of stamping out indigenous religious practices in favor of Catholicism. At times, they were willing to use violent means of coercion themselves.

Although the reconnaissance mission to the far north predated the New Laws by three years, Mendoza was already thinking in terms of carrying out “pacification” (not “conquest”) by protecting the lives and interests of “the good of the people of the land.” Under these circumstances, Mendoza chose Fray Marcos de Niza to lead the venture northward.

Niza came with the endorsement of Bishop Juan de Zumárraga, one of the most powerful ecclesiastical leaders in the early colonial period. Niza was among the Franciscans that accompanied Francisco Pizarro’s mission to subdue the Inca Empire in the Andes. He longed for another adventure and, like most other Franciscans, he wanted to open new mission fields. Although preparations for the journey began in November 1538, Francisco Vásquez de Coronado, acting in his role as the new governor of Nueva Galicia, was not able to escort the group to their launching point at Culiacán until the spring of 1539. Culiacán lay at the northernmost edge of Spanish settlement at the time. On March 7, 1539, Niza and Esteban set out, accompanied by a large contingent of indigenous allies that had been gathered from the surrounding areas.

Marcos de Nizas' Journey

Fray Marcos de Niza’s Journey North Route followed by Estevanico and Fray Marcos de Niza during their reconnaissance journey to locate the Seven Cities of Cíbola in 1539.

The party met with general success as it marched northward, finding native groups that received them with kindness, but also suspicion. When Niza paused to observe the Easter holiday at a native settlement known as Vacapa, Esteban pressed ahead. He was to send white crosses of different sizes back to the friar to indicate the types of societies he encountered. If he located settlements of little to moderate importance, he was to send a cross one palmo (about the width of four fingers) in proportion. The size of the crosses were to indicate the respective significance of the settlements, as well as their wealth. The largest crosses were reserved for sites that were “grander and better than New Spain.”10

Before Niza had departed Vacapa, Esteban’s messengers returned with a cross that was “the height of a man.” The messengers also reported that the advance party had received word that the Seven Cities of Cíbola lay just thirty-days’ journey beyond the point that they had reached. Niza departed once the Easter celebrations were completed, following about sixteen days behind Esteban’s group. All the while, messengers returned to the friar’s group with more news of great cities of wealth to the north, as well as crosses to indicate that they had located settlements of great substance. The messengers communicated Esteban’s faith in the validity of the reports that he had received from the natives, and Niza also wrote that he trusted the accounts he had received.

Then, on May 5, 1539, Esteban reached the first of the settlements that the Spaniards referred to as Cíbola. In reality, they arrived at the Zuni village of Hawikuh which was the westernmost of the six Zuni settlements. Zuni traditions tell of a “black Mexican” that arrived just outside of Hawikuh that fateful day. Rather than inviting him into their village, however, the Zuni people repulsed his advance with a barrage of arrows. In the skirmish, most of the advance party was killed, including Esteban himself. Two frightened survivors made their way back to Niza, reporting the tragedy at Cíbola.

Various accounts of Esteban’s death provided different explanations of the Zuni people’s reasoning. According to some, he had been treated as a “black god” during previous months, receiving gifts including turquoise, gourd rattles, clothing, and women. When he expected similar privileges of the Zunis, they turned on him. Another take is that Esteban sent his gourd rattle ahead to Hawikuh as he had done in previous peaceful encounters with new groups of people. When the one of the Zuni leaders received the rattle, he “flung it to the ground with much wrath and anger.”11 Apparently that particular gourd had originated from a group of people who were the Zuni’s enemies. By Zuni oral history accounts, Esteban was received initially at Hawikuh with great hospitality. Once inside, however, “his rude behavior toward the women and girls of the pueblo” caused the men to force him and his companions from the village.12 In his most recent biography, researcher Dennis Herrick reminds us that, “Ironically, the Zuni Indians who most writers accuse of killing Esteban are the ones who keep his memory alive in their oral history and through their ancient, traditional religion of kivas and katsinas.”13 Herrick argues that recognizing the Zuni relationship to Esteban’s memory suggests that they may not have killed him, although he apparently died somewhere near Hawikuh.

According to Fray Marcos de Niza’s official report, when the story of Esteban’s death reached him he pressed on until within sight range of Hawikuh but he made no attempts to enter the pueblo. Most scholars of the Niza reconnaissance mission, however, argue that the friar more likely turned and fled without attempting to see Cíbola. At best, he may have viewed the village of Hawikuh from a distance. Despite his lack of firsthand knowledge about the settlements that Spaniards still referred to as Cíbola, upon his return to Mexico City in late-August 1539 he reported the existence of the fabled cities. Although he did not expand on the specific types of wealth they possessed, neither did he attempt to dispel rumors that Cíbola indeed housed seven cities of gold that were of greater size and importance than Mexico City itself.