“The human brain is special. Just not that special.” —Peter Aldhous

“The only thing that separates us from the animals is our ability to accessorize.” —Clairee Belcher in Steel Magnolias

James Wide or “Jumper,” was a South African railman who had the habit of jumping between railway cars. One day things didn’t go as planned and he lost his legs. Jumper decided to look for a service animal to push his wheelchair and to help with his job as a signalman. That’s when he discovered Jack, a male chacma baboon (Papio ursinus). Jumper taught Jack to operate the railway signals, and the baboon performed his duties admirably until one day a passenger looked out the train window and saw a baboon operating the switches. An investigation ensued, and Jack was temporarily relieved of his duties. Desperate, Jumper managed to arrange a demonstration of Jack’s abilities to railway officials. After watching Jack operate the signals, the railway authorities hired him and put him on the payroll. It is said that he was paid in beer and food, and he never made an error.

Compared to other species, humans stand out as being a highly successful in terms of our technology, our ability to communicate, and our propensity to adapt to all sorts of environments. Philosophers and scholars have long discussed and debated exactly how our species is different. Sometimes though, there is a hidden assumption that humans are better than other species, given our particular suite of talents. This point of view where all species are judged based on a human standard is called anthropocentrism. Rather than focus on who is better, a completely subjective endeavor, anthropologists are more interested in figuring out how we came to be such a successful species.

Anthropology, with its holistic approach and emphasis on biology and culture, past and present, is well-suited to investigating the question of human uniqueness. We know that humans share the same basic building blocks of life with other organisms, namely the DNA molecule (and RNA). Within DNA are genes that code for amino acids, which in turn combine to build proteins, which instruct cells on what to do. Very different species share many genes in common. Homo sapiens and the fruit fly, for instance (National Human Genome Research Institute 2012). For this reason, genetic research on the “lowly” fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) is shedding light on a wide variety of human diseases—from neurological disorders to cancer to drug abuse. In this sense, the fundamental chemistry of life is not at all unique to humans.

On the contrary, our genetic code serves as the basis for all plant and animal life on Earth. The question then becomes what other features might have given humans the upper hand?

We have about 60 percent of our genes in common with the fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster).

Tool Use

One early feature that anthropologists pointed to as uniquely human is tool use. Archaeologist Kenneth Oakley’s 1959 book Man the Toolmaker was influential in characterizing tool use as being quintessentially human. Though there are gray areas, a tool can be generally defined as an object used to modify the shape, condition, or location of another object. The term tool typically refers to an object that is not permanently attached, so a monkey using its tail to grab an object does not qualify. There is also debate about whether bird nests and hermit crab shells are tools. There are other nebulous examples: When an ape throws its own feces at unsuspecting zoo-goers, is that tool use? Despite some ambiguity in definition, a tool doesn’t have to be something as complex as an electric drill or a sewing machine, and tools don’t even require hands.

Jane Goodall’s famous work in Gombe Stream National Park in Tanzania disproved the notion that tools were uniquely human. Goodall discovered that chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) modified plant stems and inserted them into termite nests to extract the insects, a source of protein for the chimps. Termite fishing, as it is sometimes called, qualifies as tool use. Following Goodall’s discovery, paleoanthropologist Louis Leakey famously quipped, “Now we must redefine tool, redefine Man, or accept chimpanzees as humans.” Since Goodall’s groundbreaking work, numerous examples of animal tool use have come to light. Chimpanzees use several different tools in addition to termite sticks: logs and anvils to crack nuts, leaf sponges, and more recently a kind of spear, which are large modified sticks used to hunt smaller primates. Gorillas use tools in captive contexts, and recently one wild female gorilla used a stick to test the depth of a watering hole. Kanzi, a captive bonobo chimpanzee, the subject of study by psychologist Sue Savage-Rumbaugh, has been taught to create sharp stone flakes to cut a rope and retrieve a hidden snack. Capuchin monkeys in Brazil and macaques in Thailand use rocks to crack open nuts. Otters use rocks to open shellfish, dolphins use sea sponges to scrounge for food on the seafloor, and crows have been shown to use sticks to access difficult-to-reach food and even make wire hooks. All of these examples qualify as tools.

While other animals use simple tools, human tools are astonishingly complex. We can, for example, make tools to make other tools. Our capacity for tool innovation lies in our ability to put together old ideas in new ways. As Steve Jobs famously said in his Stanford commencement speech, “Creativity is just connecting things. When you ask creative people how they did something, they feel a little guilty because they didn’t really do it, they just saw something. It seemed obvious to them after a while.” Plus, human technology is cumulative, in that we can build on previous innovations. As one CNM student eloquently put it, “Humans have the ability to build on the strengths of others.”

Thomas Edison is credited for inventing the light bulb, but as Steven Johnson’s book and PBS series How We Got to Now makes clear, there were many patented versions of the light bulb before Edison perfected it. Edison thought of himself as a “sponge” of ideas more than an inventor. All sorts of discoveries and innovations had to be made before the lightbulb or smartphone was possible—mining, metallurgy, batteries, plastics, glass-making, and countless others. In this light, the invention of the iPhone started when someone sparked the first fire hundreds of thousands of years ago. Because technology is cumulative and many people make small contributions over time, there’s probably no single person alive today that can make an iPhone from raw materials from start to finish. one. This concept of cumulative technology is captured in Thomas Thwaites’ TED talk where he describes how he attempted to build a toaster from scratch. The capacity to build upon prior discoveries, combine tools, and pass along knowledge to the next generation is an incredibly useful and powerful characteristic of humans.

Culture

Culture is very typically thought of as inherently human and only human. After all, anthropologist E.B. Tylor defined culture as that complex whole acquired by “Man.” The definition of culture as shared traditions, beliefs, and values that are transmitted through learning allows us to ask whether humans are the only cultural species. With this definition of culture, we can ask whether non-human animals have anything that resembles learned behaviors.

The story of animal culture begins with monkeys. In the 1950s on the Japanese island of Koshima, researchers were studying Japanese macaques (Macaca fuscata). Sweet potatoes were put out to entice the macaques into the study area. One day a female monkey named Imo (“Potato” in Japanese) got fed up with all the sand on her potatoes and began washing them in the salty sea. The water not only cleaned off the annoying sandy grit but also seasoned them with salt. Thus, a monkey “life hack” was born. Other monkeys soon followed suit until virtually all the macaques were washing the potatoes; the youngest were the “early adopters” and adult males were the last to adopt the practice. Even in the next generation of macaques, the practice of potato washing continued, indicating that the practice was transmitted through learning. While it might not seem much of a feat compared to the complexity of making a toaster, it can be considered a form of culture nonetheless.

Chimpanzees also have learned tool traditions. Young chimpanzees observe their mothers using termite sticks and other tools, and over time become adept at making and using the tools themselves. What’s more, different populations of chimps have different tool traditions that are passed down and maintained. Primatologists like Martin Muller of the University of New Mexico and co-director of the Kibale Chimpanzee Project study chimpanzee tool traditions or “cultures.”

Robert Sapolsky, a primatologist and neuroscientist who studies baboons in east Africa, experienced a sad but interesting case of culture among olive baboons (Papio anubis). Male baboons in his study group were visiting a garbage dump at an African tourist lodge in Kenya called Olemelepo. Parts of cattle sick with tuberculosis were discarded in the dump where the baboons fed. As a result of feeding patterns, the more aggressive males in the troop died from the disease, leaving behind male baboons that were less aggressive. The deaths also left far more adult females than adult males overall.

This led to what Sapolsky (2004) describes as a “pacific culture” or peaceful culture among the baboons. There was more grooming, the dominant males were more tolerant of lower-ranking males, and there were lower stress levels as measured by cortisol in lower-ranking baboons. Even when new males immigrated into the troop, the “culture of peace” persisted, indicating that this “hippie” baboon culture was learned.

Rescued orangutans released in Borneo learned to use soap from local villagers and have been known to steal soap to wash up. More surprising is that this tradition was spread to wild orangutans who have been known to steal soap to wash up, creating a culture of cleanliness.

Other traditions in the animal world seem more bizarre than functional, and in that regard even more like human culture. Anthropologist Susan Perry, director of the Lomas Barbudal Monkey Project in Costa Rica, has studied an interesting cultural tradition in white-faced capuchin monkeys.

One group of capuchins has developed a propensity for probing the eyeballs of other monkeys with their fingers up to the first knuckle. These odd eye-poking sessions can last up to an hour.

The practice appears to be uncomfortable for the recipient, but the monkey makes no attempt to remove their buddy’s finger. Perry suggests the behavior may be a kind of test of friendship, like a monkey “trust-fall.” The reason for this bizarre cultural tradition, however, remains an open question.

Women in a circle clapping; they got into trance. The next day, I interviewed the women and said, “Why do you do this?” They gave me the answer, “Because it gives us meaning.” Their answer has been my answer for culture since that time.

For many anthropologists, culture is not just about learned traditions, but rather the assignment of meaning and value to those traditions. We pass along beliefs, values, stories, and social traditions that are loaded with meaning. Our beliefs are connected to how we interpret things or how we assign meaning to objects and behaviors. An enormous amount of importance, for instance, is placed on how people dress, speak, eat, act, and pray because we assign these things meaning. Even small things that we do are loaded with meaning, like whether we greet with a handshake, a hug, two kisses on the cheek, or a bow. And sometimes we even things with meaning where there really is none. There’s an old story about a family cutting the ends off the pot roast because that’s how it was always done. When the family finally asked great-grandma, she explained that the old stovepipe oven she used just wasn’t big enough, so she cut off the ends. Cultural meanings are inter-connected such that they form a kind of web that we become entangled in as we are enculturated. The famous cellist, Yo Yo Ma studied anthropology and got some insight into both music and meaning. He explains (Marchese 2020),

The bushmen of the Kalahari desert — I actually studied them, and I loved that group. I spent time there. And the thing — I’ll give you the fast takeaway — is that they did trance dancing. They did this dance for hours. Women in a circle clapping; they got into trance. The next day, I interviewed the women and said, “Why do you do this?” They gave me the answer, “Because it gives us meaning.” Their answer has been my answer for culture since that time.

Other species don’t seem to have these deeply held values and meaning embedded in actions and objects. As one CNM student put it, “I doubt that monkeys have strong feelings about abortion and helicopter parenting.” Looking cross-culturally, beliefs and values are incredibly varied. As Robert Sapolsky puts it, “Human nature is extraordinarily malleable, and I think that’s the most defining thing about our nature” (Illing 2017). It is a primary goal of cultural anthropology to recognize and understand these incredibly diverse cultural webs of meaning.

Human belief is quite powerful and often hard to change. The placebo effect demonstrates this nicely. In one study, 13 boys who reported being highly allergic to Japanese lacquer trees were told that their arms were being brushed by the poison-ivy-like leaves. In reality, those leaves were from a harmless plant. And yet all 13 boys experienced a reaction to the harmless plant. What’s more, the irritating lacquer leaves were rubbed on the other arm, and only two boys experienced a reaction. Such is the power of human belief. Our cultural beliefs are even stronger and are reinforced daily. Think about your own beliefs about subjects like wearing clothes, gun control, or how children should be raised. People can live their entire lives without recognizing that their unshakeable beliefs come from their culture, and are continuously reinforced by stories, rituals, and interacting with like-minded people. Even businesses have their own mini-cultures. As management consultant and author Peter Drucker Cultural puts it, “Culture eats strategy for breakfast,” meaning businesspeople ignore their company’s culture at their own peril. Beliefs are so strong that people sometimes kill or are willing to die for them, and sometimes they are willing to put their own children in jeopardy for them. It is only when you look outside your own culture that you see outside the small box of belief and meaning that is your culture. Indeed, many people never step foot outside the box.

Cooperation and Reciprocity

An African proverb says that if you want to go quickly, go alone, if you want to go far, go with others. All of us are familiar with reciprocity, the equal exchange of favors, in our daily lives. If you help a friend move, you expect that friend to come help you if your car suddenly breaks down and you can’t get to your anthropology class. this ability to cooperate with others is extremely important for humans and other primates.

Primatologist Frans de Waal explains that reciprocity makes cooperation possible in monkey and ape species. Experiments with captive primates have shown that a pair of chimpanzees can coordinate efforts to pull in a heavy object with a treat on top. Elephants are able to perform a similar task. In another experiment, capuchin monkeys are shown to reject unequal pay. When one is paid in cucumbers and another is paid in grapes for the same task, the cucumber monkey rejects the cucumber payment.

Chimpanzee life in the wild is likewise full of reciprocal favors and cooperation. Chimpanzee grooming is not purely for hygiene but is a means to create bonds and alliances with other chimpanzees. In the chimpanzee world, there is a pecking order or social hierarchy for both male and female chimpanzees, but males tend to be dominant overall. For males to rise through the ranks, they need to make friends and have social backing. Male chimps groom each other and return the favor—reciprocate—by backing each other up in male-male contests. No matter how strong a chimp you are, you need influential friends to get to the top. The politically savvy chimps, not necessarily the strongest chimps, get promoted. Moreover, when fights do break out between friends, chimps will come together and hug to reconcile, highlighting the importance of maintaining the reciprocal partnership. Because cooperation is based on reciprocity, chimps tend to cooperate with other chimps that they know and see regularly. This cooperation extends to perhaps 60 to 100 individuals—the size of a chimpanzee troop.

Non-primates are also known to cooperate, sometimes on huge scales. Ants, for instance, cooperate to the point where a colony is considered a single organism. They can be remarkably inflexible, though, by human standards. Biologist E.O. Wilson famously painted oleic acid onto the bodies of select ants. Oleic acid signals that an ant is dead. Thus, perfectly healthy ants would be carted off to the dead ant pile, despite the kicking and thrashing of the unfortunate pheromone-coated ant. This rigid cooperation is quite different than the cooperation based on reciprocity common in primates.

So very often, we hear news stories about humans not cooperating. But compared with many other animals, we are a remarkably cooperative species. Psychologist and co-founder of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Michael Tomasello points out that humans have what he calls “shared intentionality,” understanding each other’s intentions and working toward a common goal. Humans can “put our heads together” and solve problems that alone we could not solve.

Even babies want to share their experiences by pointing to objects before they can talk. Small children will help out adults when they appear to be struggling. Tomasello notes that children also want to know the right way of doing something, and once learned, will enforce those social norms, also known as “tattling.”

Humans can be remarkably violent, as our World Wars have shown. And yet, we can be remarkably social in the most unexpected of circumstances. During World War I, British and German troops were in a standoff, dug into trenches along the Western Front. During the day, the soldiers would be trying to kill each other. In the evening, informal truces arose such that the enemy could retrieve the dead from the “No Man’s land” between the military positions. During Christmas of 1914, enemy soldiers shouted Christmas greetings to each other, sang carols together, and even exchanged small gifts of food and tobacco.

The extent of human cooperation is vast. People cooperate in sports teams, churches, classrooms, workplaces, and millions of humans can come together for a common political cause or raise money for people they have never met. Instead of cooperating with the expectation of return, we often cooperate under a common cultural value or practice. A classroom full of strange chimps would be utter chaos, not to mention incredibly dangerous. But every semester, perfect strangers come together at CNM to take a course in anthropology or Spanish, or psychology without a problem. We can do this because we share common goals, shared values about how to treat each other, and shared ideas about what to do in a classroom setting. Yes, humans can be nasty, but we can also cooperate on a grand scale based on culture alone. Today, the Internet allows us to form virtual cooperative communities with millions of people we rarely see or have never even met. Chimps, on the other hand, don’t cooperate based on culture—either they know you personally, or you are an outsider, and therefore, a potential threat.

Intelligences

“Intelligence” is a term people use daily, but they don’t always have a good working definition. In Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are? Primatologist Frans de Waal defines “cognition” as the ability to take sensory input from the environment, convert that input into knowledge, and then apply that knowledge. The ability to complete this process successfully can be thought of as intelligence. Co-founder of the Future of Life Institute, Max Tegmark (2017), defines intelligence simply as “the ability to achieve complex goals”. French philosopher and scientist Rene Descartes (1629–1649) thought that while humans were governed by reason, animals were more like “flesh machines” responding to stimuli in a mechanistic way. Today, we know that chimpanzees excel at solving certain types of problems, sometimes even out-competing humans. In one test, chimpanzees were given a clear tube with a peanut at the bottom. Some chimpanzees figured out that if you add water, the peanut will float to the top. Try this test on your favorite human and see how long it takes them to figure it out.

In another interesting case, Ayumu, a chimpanzee raised in captivity at Japan’s Primate Research Institute. Ayumu’s study involved remembering a sequence of numbers to get a treat. Ayumu was able to perform this task with lightning speed, whereas human subjects failed miserably even after training. You can try a version of this game here: https://scratch.mit.edu/projects/213935354/ As primatologist Nick Newton-Fisher sensibly explains, “the apes are better at doing chimps things, and we’re are better at doing human things.” It is also possible that Ayumu simply has practiced all his life and has little else to worry about. This can happen in humans as well. László Polgár thought that children could be taught anything if they started young and focused on it completely. He immersed his three daughters in chess–Zsuzsa, Zsófia, and Judit–and they all three became Grandmasters or International Masters in chess. Judit is considered the best female player ever. And yet, when it comes to intelligence, it is very hard to compare different species because they all apply knowledge to solve problems in their environments but do so differently. Because of this dilemma, Frans de Waal argues that it is not useful to compare species on a single scale, but rather to speak of intelligences.

Frans de Waal writes: “Many people think that animals are trapped in the present, but there is increasing evidence that they think ahead and plan for the future. Not just in an instinctive manner, the way squirrels do when they collect nuts for the winter (the squirrels do not know about winter, certainly not the first-year juveniles, but still show the behavior).” Ravens have been shown to select a token from a series of objects that they can barter with for a treat (Cabadayi and Osvath 2017). Even if the treat is delayed by a day, the ravens will go for the token and not other distracting objects. A captive chimpanzee at the Furuvik Zoo in Sweden stockpiled stones that he would later hurl at unsuspecting zoo-goers. He even took straw from his bedding to hide the stones for future attacks.

But maybe there is something special about the human brain. After all, our ability to solve technical problems is unparalleled, and we can plan years in the future, even long after we are gone. For example, The Long Now 10,000 Year Clock, currently under construction, is intended to last 10,000 years. If we look at sheer brain size, humans are not even close to the top of the heap. Sperm whales have the largest brains overall and elephants have the largest brains of terrestrial animals. But we humans have a larger than expected brain given our body size—about seven times bigger than expected compared to other mammals, and three times bigger compared to other primates. This measure is called the encephalization quotient. But comparing humans to other mammals in terms of expected brain size is not straightforward, as brain size and number of neurons is not always linear.

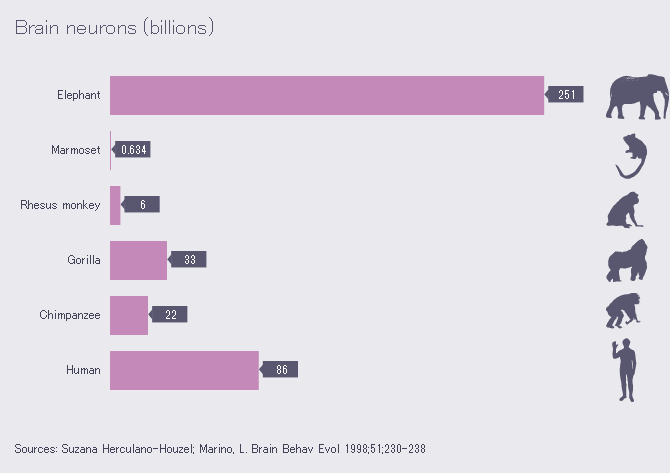

According to Brazilian neuroscientist Suzana Herculano-Houzel, the number of neurons and where they are in the brain are more significant than overall size. Humans have, by Herculano-Houzel’s (2012) estimate, 86 billion neurons, and we have a large number of neurons in our expanded cerebral cortex (16 billion), the wrinkled outer rind of the brain and the seat of complex cognition.

Humans rank second for neurons in the cerebral cortex, sandwiched between different species of whales. Even though we are not in the lead for cerebral cortex neurons, Herculano-Houzel thinks these brain cells may be a significant contributing factor in our flexible intelligence.

How many neurons there are and where they are in the brain are more important than brain size.

Mirror, Mirror: Self Recognition

Visual anthropologist Edmund Carpenter introduced mirrors to remote Papua New Guineans in the 1960s. This was the first time the Papua New Guineans had ever seen their own image. He writes in Oh What a Blow that Phantom Gave Me! “They were paralyzed. After their first started response— covering their mouths and ducking their heads—they stood transfixed, staring at their images, only their stomach muscles betraying great tension. In a matter of days, however, they groomed themselves openly before mirrors” (1976:112). Carpenter also took Polaroid photos of Papua New Guineans. Initially, people did not recognize the photos for what they were, but when Carpenter pointed out features of human faces, they realized what was happening. Men would slip away to study it alone. In no time though, villagers were taking photos of each other and men began to wear their photos on their foreheads. Carpenter later wondered if bringing these items to the Papua New Guineans was a mistake, wondering if he had helped to create a new sense of “the private individual” and social alienation (1976:120).

Humans can recognize themselves and spend an extraordinary amount of time and energy embellishing their bodies with makeup, tattoos, clothing, and hats. Clairee Belcher in Steel Magnolias advised, “What separates us from the beasts is our ability to accessorize.” She has a point, given our obsession with outward appearances and the amount of money we spend on clothing, cosmetics, tattoos, jewelry, and braces.

And yet, some animals can recognize themselves in mirrors as well. This is demonstrated through the mark test or the mirror test. First, a colored mark is secretly placed on the animal’s face. When the animal sees itself in the mirror, it touches the mark. Chimpanzees, orangutans, some gorillas, Eurasian magpies, dolphins, and an Asian elephant have been shown to pass the mark test, while monkeys, dogs, and cats all fail. This ability is called bodily self-recognition and indicates that those animals are aware that the image in the mirror represents them.

The mark test, however, has been criticized because it is geared toward animals that rely heavily on vision as opposed to other senses like hearing or smell. As Ed Yong points out in Immense World, other species’ perceptual worlds are vastly different from our own. Birds can sense the earth’s magnetic field. bees see ultraviolet light, pit vipers can sense infrared radiation, and mosquitos can detect carbon dioxide which they use to locate you and suck your blood. Also, bodily recognition is not the same as mental self-awareness—understanding oneself as an “I.” Any casual familiarity with social media makes it clear that humans are interested and sometimes even obsessed with their identity, the values and beliefs they project to the world.

Chimps have been known to do something akin to human bodily adornment, for no obvious reason. At the Chimfunshi Wildlife Reserve in Zambia, a chimpanzee named Julie one day stuck a piece of grass in her ear and kept it there (Main 2014). She continued with this strange behavior until one day other chimps began to do the same. This “fashion statement” is interesting because it doesn’t have an obvious function.

Human bodily decoration appears to be a bit different from chimp fashion or bower bird nesting building, in that our embellishments are also loaded with meaning. Engagement and wedding rings are a symbol, as are tattoos and clothing styles. They send signals about the identity of the person, and people form communities very often with people sending similar signals. Researcher Michelle Langley (2018) writes “Some choices are conscious, others not so much – but everything we wear is telling a story…This process of agreeing amongst ourselves that a certain thing can stand for something completely different is what makes us human.” Langley argues that early humans used these external symbols, bodily decoration, to expand their communities beyond the people they saw daily.

Art

Art is all around us every day: poetry, literature, music, paintings, murals, television, films, dance, and even something as simple as a tattoo. Some animals do create images that are symmetrical or aesthetically pleasing from a color point of view. Satin bower birds famously create bowers decorated with bright blue objects to allure female bower birds. Pufferfish create symmetrical designs with their fins on the sea floor to attract females. He even decorates his creation with shells. Some chimps even paint and appear to enjoy the process. Birds sing beautiful melodies to attract mates and defend territories.

Humans though, take art to another level to provoke an emotional or mental response. We decorate our bodies with meaningful designs and images as well as our environment. We create patterned sounds that evoke emotion and often tell a story, which we call music. Sometimes our art is representational, depicting things in our environment or even imaginary beings and settings. In many ways, we create our own reality, new worlds using art—in how we present ourselves, in how we craft our environment, and in the music we immerse ourselves in. And art is intimately tied to the web of meaning that is human culture. As Nathan Letts (2017) writes, “Without culture, there really can’t be art, as we know it, because art cannot exist separate from culture. Art reflects culture, transmits culture, shapes culture, and comments on culture.” Human art does more than attract a mate, it creates and transmits worlds.

“Art reflects culture, transmits culture, shapes culture, and comments on culture.”

Emotion

One of the most interesting lines of inquiry in recent years into the question of animal cognition is their emotional lives. But it was once thought that animals had no emotion. Philosopher Nicolas Malebranche (1638–1713) put it this way: “animals eat without pleasure, cry without pain, grow without knowing it: they desire nothing, fear nothing, know nothing.” By the mid-1900s, anthropomorphizing, meaning assigning human qualities to an entity, was seen as unscientific among the behaviorist school (which focused on behavior rather than the mind), because animal emotion was impossible to measure quantitatively. All that could be documented unquestioningly was behavior. In the 1960s, Jane Goodall’s work paved the way for a reconsideration of animal emotion. Unaware of the prevailing behaviorist paradigm (a paradigm is a school of thought) in animal studies, she happily assigned all the chimpanzees she encountered personalized names like Flo, David Graybeard, and Mike, completely unaware that other researchers were labeling their animal subjects with numbers. Likewise, Goodall did not hesitate to use words like “jealous” and “angry” to describe chimpanzee emotional states and wrote about chimpanzees as if they had individual personalities. Goodall had no idea that these practices were viewed as unscientific among behaviorists and she was vilified for her methods.

Behaviorists were especially skeptical about whether animals could experience emotions more complex than fear or anger. One area that was off-limits to research was compassion or empathy. Today, empathy in animals is being actively studied. We know, for example, that mammals share the neural seat of emotion—the brain’s limbic system—with humans. And the Internet is full of anecdotal stories and video evidence of animals saving other animals from harm. Controlled experiments by psychologist Russell Church show similar results. In a laboratory experiment, a rat would inadvertently deliver an electric shock to another rat in a separate cage when they pressed the lever to get a treat. Once the lever-pressing rats learned of this correspondence, they denied themselves the treat. Church’s article entitled “Emotional Reactions of Rats to the Pain of Others” met the same skepticism from behaviorists as Jane Goodall’s work with chimpanzees. More recently, rats have been shown to free other rats even in the presence of a chocolate treat. In this case, rats free the other rat as often as they go straight for the chocolate (Ferber 2011).

The tide has turned on animal emotion. Jane Goodall writes in “Life and Death at Gombe”, “Those who have worked closely with chimpanzees agree that their emotions—pleasure, sadness, curiosity, alarm, rage—seem very similar to our own, though this is difficult to prove.” In his article “Animal Spirits” philosopher Stephen T. Asma points out that fear, lust, and care are what allow animals to flee predators, mate, and care for their young. He writes, “We share a rich emotional life with our animal brethren because emotions helped us all survive in a hostile world. Indeed, the more we understand what mammals have in common, the more we have to rethink everything about even our specifically human intelligence.”

Other more subtle emotions, like grief, are becoming of interest to animal researchers and anthropologists alike. How Animals Grieve by Barbara King describes how cats and dogs will alter their routines, refuse to eat, and undergo a change in personality after a companion dies. Animals in the wild also alter their behavior following the death of a family member. There are numerous examples of elephants returning to the site of a deceased family member or even returning bones that have been removed by humans to their original location. There is anecdotal evidence (unconfirmed stories) of elephants covering their dead with dirt.

Kaeli Swift has documented numerous crows converging upon a dead crow, then launching into a series of caws followed by silence (Marshall-Chalmers 2020). These are sometimes referred to as “crow funerals.” Swift has even evoked “crow funerals” with taxidermied crows.

Language

Language in animals is a source of fierce debate, and like so many other terms, it depends on how you define it. Scholars like Jane Goodall, Frans de Waal, and Noam Chomsky do not think animals have language in the way that humans have language. Language seems to be a specialization of humans. At the same time, some features of language can be seen in animal species in both captive environments and in the wild. Apes like Washoe the chimpanzee, Kanzi the bonobo, and Koko the gorilla have been taught to use words in American Sign Language or symbols called lexigrams to communicate with humans. Their ability to use signs to refer to things in their environment is remarkable. Yet other key aspects of language, like grammar, are not well developed in animal communication. We will look at this subject and the signing apes in more detail in a later chapter.

Awe, Spirituality, and Meaning

Of all the comparisons between non-human animals and humans, spirituality seems the most uniquely human. Psychologist Jonathan Haidt likes to refer to humans, not as Homo sapiens (thinking man), but Homo spiritualis (spiritual man). For Haidt, it is our spiritual life and not our rational, calculating minds that make us stand out in the animal crowd. In many ways, we are decidedly non-rational.

Recently, Jane Goodall has expressed the idea that chimps can feel, but not analyze, a sense of awe and wonder (Jane Goodall Institute 2011). She defines awe as amazement at things outside ourselves and says that chimpanzees experience awe and wonder during something called a waterfall display. At Gombe National Park, waterfall displays consist of tossing in stones, rhythmically swaying, and swinging from nearby branches over the falls while vocalizing. Goodall suggests that the display is a kind of dance or an emotional state that the chimps can’t analyze. I experienced something similar when studying mantled howler monkeys (Alouatta palliata) in Costa Rica. Not only would the monkeys howl when threatened by other male monkeys, but they would howl at the sound of thunder and an oncoming rain storm. Low-pitched frequencies in general seemed to elicit a howling response.

In West Africa, chimps throw stones at certain trees, leaving behind numerous caches of stones around the tree (Kuhl et al. 2016). The chimps who throw stones tend to be males, (though some females do as well) and also exhibit behavior seen during aggressive displays—hair erect, pant hooting, and bipedal stance. It is not clear why chimpanzees would engage in this behavior around a particular tree, but it could be an extension of the foot drumming which is a normal part of a male dominance display. The rock throwing may serve to amplify the sound and heighten the effect of the display. The behavior may also be learned, as it only appears in West African populations. Some news reports enthusiastically labeled the behavior as “chimpanzee religion,” “chimp temples,” or, perhaps worst of all, “sacred monkey trees.” While there is still much debate about what the rock-throwing behavior and waterfall displays mean, the arena of religion, ritual, and spirituality seems if not unique to humans, then the least well-represented feature in non-human animals. But, as we will see in Chapter 10, there are other species in the fossil record, like Homo naledi, that quite possibly had a sense of spirituality and may have even deliberately deposited their dead in caves for ritual purposes.

Discussion

By comparing humans and their behavior to other species, we can get a better idea of what it means to be human. Though we share the basic ingredients of all life on earth, DNA, we can see that humans overlap in many features with other organisms including tool use, emotion, cooperation, reciprocity, bodily self-recognition, reasoning and intelligence, and perhaps even some aspects of culture, language and the spiritual. We now turn to a fundamental activity of all species, getting food.

Lesson Quiz here