The flow of power and authority along the northernmost section of the Camino Real was reversed following the success of the 1680 Pueblo Revolt. Unified Pueblo warriors forced Spanish colonists into refuge at El Paso del Norte (present day Ciudad Juárez). As if the defeat endured in 1680 was not enough, the next two decades were marked by other indigenous revolts, and threats of uprising, all across the far-northern frontier of New Spain. The Spaniards referred to this time period as the Great Northern Rebellion. Unlike the case of the Pueblo Revolt, however, Spanish forces acted quickly and brutally to quash other potential uprisings.

Although a mission congregation of Manso and Suma peoples had been established in 1659 at the mission called Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe del Paso del Norte and a few Spanish families inhabited the area, the creation of the villa of El Paso del Norte did not take place until 1680 when Governor Antonio de Otermín arrived there with the refugees from New Mexico. The people settled in several different temporary camps until permanent homes were constructed. In 1683 a presidio was established to defend the settlement against attacks of nomadic natives in the region. It was initially built eighteen miles to the south of the mission, but relocated the following year to the mission itself due to a general uprising that occurred among various indigenous peoples in Nueva Vizcaya.

Other groups of refugees settled at a site called San Lorenzo, situated four miles downstream along the Rio Grande at the Pueblo of the same name. Additionally, two small groups of Piro Indians had relocated to the area from New Mexico. Isleta people fled with the lieutenant governor when hostilities broke out in August 1680. Their descendants continue to inhabit the area of Ysleta, Texas, near present-day El Paso. Despite the resolve of most of the refugees from New Mexico, a large number of them abandoned the colony after the Pueblo Revolt.

In evaluating the settlers’ decision of whether or not to abandon the colony, we must consider the fact that by 1680 most Spanish, Pueblo, and mestizo residents of New Mexico had grown up under the Spanish-colonial system. No matter their ethnic or cultural affiliation, they had lived their lives together. Most of the refugees at El Paso considered New Mexican properties to be the legacy of their families, as did, of course, Pueblo and mestizo peoples who remained behind. At least twelve families of Spanish descent remained among the Pueblo peoples after 1680, indicating the extent to which accommodations had defined the seventeenth century in the colony.

To understand the successful reconquest of New Mexico, orchestrated by Diego de Vargas, knowledge of the larger context of events that were taking place throughout the northern frontier of New Spain is crucial. In 1697, the mission of Nombre de Dios was established about 265 miles south of El Paso del Norte. The mission was initially founded to serve a congregation of Conchos people that inhabited the areas surrounding it, but in subsequent years, more and more people of Spanish descent arrived in the area due to the prospect of mining. By the early eighteenth century, Ciudad Chihuahua developed on the site immediately surrounding the mission due to the discovery of nearby silver deposits. The city was important to the reinvigorated New Mexico colony as a way station for trade along the Camino Real. Miners and farmers filtered slowly into the settlement throughout the 1700s.

El Paso Missions

El Paso became a thriving center with a diverse mix of people. See how El Paso was formed, and find out about the events before the Spanish came to El Paso.

Prior to the founding of Ciudad Chihuahua, however, the region of northern Nueva Vizcaya was the scene of general unrest in the wake of the Pueblo Revolt. Understandably, in the years following the revolt, Spanish inhabitants of Nueva Vizcaya feared that the desire for revenge had spread to virtually every native group in the northern section of New Spain. For the first time, the Concho, Janos, Jocome, Manso, and Suma peoples confederated. By and large, most indigenous peoples had maintained their independent identities even in the face of Spanish colonization. Now, various groups came together, through negotiated alliances and intermarriage, to stand against the colonizers—at least, such was the conclusion of Spanish officials. In the context of the Pueblo Revolt—the only successful indigenous rebellion against a European power—it is easy to understand why Spanish suspicion reached a crescendo.

Spanish colonists never forgot that native peoples were the first inhabitants of northern New Spain. The refugees at El Paso certainly could not neglect that fact. As seemingly consistent reports of native unrest filtered into El Paso del Norte, Spanish settlers lived in constant fear of retribution for the conquest. Rumors filtered in that a group of natives had attacked and burned to the ground the chapel at Janos. Sumas attacked Santa Gertrudís, mines were ruined, haciendas set ablaze, cattle and horses driven off.

Calamities that beset the region’s indigenous peoples only intensified their hostility toward the Spanish and continued the cycle of suspicion and rumors. The drought and famine that had plagued the New Mexico colony since the late 1660s also affected people in Nueva Vizcaya. To make matters worse, epidemics of smallpox, measles, and dysentery devastated indigenous communities. Such contagions hit newly established Jesuit missions particularly hard. By some estimates, approximately one-third of the entire native population died due to famine and disease.

With all of these factors multiplying, Spanish inhabitants of the area in and around El Paso del Norte heard a terrifying rumor that a knotted rope had been distributed among local native peoples. They fired off alarmed and desperate pleas to Mexico City for reinforcements and arms, but distance meant that such aid would not be quickly forthcoming. By the long, hot summer of 1699, colonists believed that a full-scale rebellion might break out any day. Their fears were not merely the product of rumor and apprehension. The Tarahumara people had a history of turning against friars at mission settlements in Nueva Vizcaya that dated back to the early 1600s. In 1652, for example, a widespread Tarahumara uprising ground Jesuit missionary work to a halt in the Sierra Madres. Their political cooperation with other tribes was a product of the crises of the era, as well as the growing practice of intermarriage between their peoples.

In what some historians termed the Great Northern Revolt, raids led by nomadic peoples intensified across the entire northern frontier. From the Spanish perspective, the Pueblo Revolt had created a drive for rebellion among all indigenous peoples in the north. There is some evidence that Pueblo peoples had been in contact with native groups in Nueva Vizcaya, but the fact also remains that raiding typically intensified during times of climatic and ecological crisis. Tarahumara groups orchestrated much of the cooperation between themselves and the other native groups of Nueva Vizcaya. Although no single, coordinated insurrection came together, several successful skirmishes against Spanish outposts and missions resulted. At Yepómera and Tutuaca, warriors killed Jesuit missionaries.

Throughout the 1690s, military officials made routine inspections of missions and indigenous settlements in the Sierra Madres in order to take preemptive action against potential uprisings. Such inspections involved the taking of a census in order to determine the movements of the native peoples. Generally, the Spanish were pleased that their presence seemed to generate the desired level of intimidation. They interrogated many of the prominent members of each community or band, and then admonished the people to live upright Catholic lives before moving on to the next settlement. In a few cases, however, inspectors found Tarahumara people guilty of treasonous actions and hung them on the spot.

Following this pattern, Spanish generals smothered a larger revolt near Casas Grandes that seemed to threaten Spain’s grip on the entire region. Summary executions, combined with violent military campaigns, quelled the specter of further revolution on the heels of the Pueblo Revolt. Intensified violence was the Spanish method of restoring peace to the northern frontier. Such a peace was always uneasy, however, because of its foundation in brutality and the Spanish drive for domination. Additionally, the rising prominence of Apache, and then Comanche, bands during the eighteenth century provided regular reminders of the tenuous position in which the colonists found themselves.

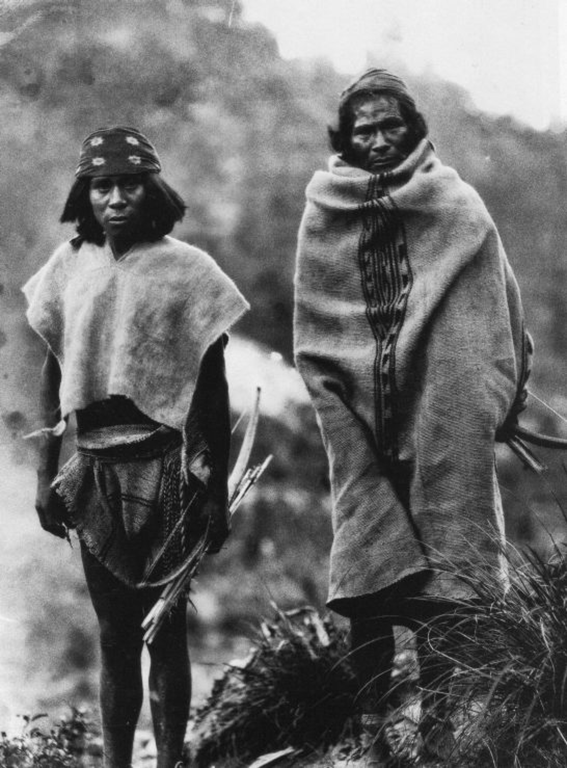

Meet the Tarahumara

Discover the traditions and ways of life for the Tarahumara. Their celebrations and events, such as “foot throwing,” make them famous for their unique way of life.

As in 1607-1608, at the time of Juan de Oñate’s resignation, the New Mexico colony once again found itself at a crossroads between 1680 and 1692. Royal officials again debated the viability of maintaining the isolated settlement, and some even considered abandoning the Rio Grande corridor altogether. Many of the New Mexico settlers deserted the colony after the harrowing and narrow escape from Santa Fe in late 1680. Only seventy families accompanied Governor Diego de Vargas when Santa Fe was resettled at the end of December 1693. For those who remained, the desire to reclaim their families’ homes and properties was strong. Most of the refugees had known no other life than that of the New Mexico colony.

Only a few months after the colonists’ flight from Santa Fe and the Rio Abajo settlements near Isleta Pueblo, Governor Antonio de Otermín attempted a reconquest. He had the added impetus of salvaging his reputation for leadership and strength. His return to New Mexico, however, was far from successful. Otermín’s party witnessed destruction at every site they visited. Piro peoples had completely abandoned the southern Pueblos and churches and kivas alike lay in ruin, suggesting that Apache attacks were to blame. Otermín forced the remaining Isletas to pledge their allegiance once again to Spain (many of the Isleta people had fled with Otermín’s lieutenant governor at the height of the uprising), and his troops engaged warriors at Sandia, Cochiti, Santo Domingo, and Santa Ana Pueblos. After destroying many Pueblo homes and inflicting casualties, Otermín’s forces returned to El Paso del Norte essentially empty handed.

While at Sandia, the group had conducted a small-scale investigation of the Pueblos’ motives for rising against them. Most of the survivors could not comprehend how and why the Pueblos had defeated them. Some, such as the surviving Franciscans, thought the Pueblo peoples were ungrateful. From their vantage point, they had only offered salvation and goodness. How could they reject such valuable gifts? Others among the refugees believed that the Pueblo Revolt was God’s punishment for the sins they had committed against the indigenous people. These colonists recognized their own excesses, and, at some level, seemingly wished to atone for them. The viceroy in Mexico City shared this opinion. Another group reached the exact opposite conclusion—that the revolt was the work of the devil who had possessed Pueblo leaders in order to thwart the work of God that the Spaniards had effected in New Mexico. Such people were unwilling to take responsibility for the misdeeds of late-seventeenth-century New Mexican society.

Pueblo peoples recall the interrogations somewhat differently in their collective memory. Jemez historian Joe S. Sando has suggested that their responses to the Spaniards are still considered a “legendary joke.” When Otermín demanded that a group of captive Pueblo men tell him who had orchestrated the revolt, one Keresan man replied, “Oh it was Payastiamo.” The governor persisted, asking more information about Payastiamo. The same man told Otermín that he lived “Over that way,” indicating a path toward the mountains. When asked the same set of questions, a Tewa prisoner recounted, “The leader’s name is Poheyemo. He lives up that way,” pointing to a separate mountain chain further to the north. A Towa man responded similarly, “His name is Payastiabo and he lives up that way.” The three names, Payastiamo, Poheyemo, and Payastiabo, are those of Pueblo deities who act as intermediaries between the people and the “One above the clouds.” He is generally said to live toward the north in the highest mountain peak or in the clouds. The joke was lost on the Spaniards, who believed that “Poheyemo must have been the revolt’s leader.”3

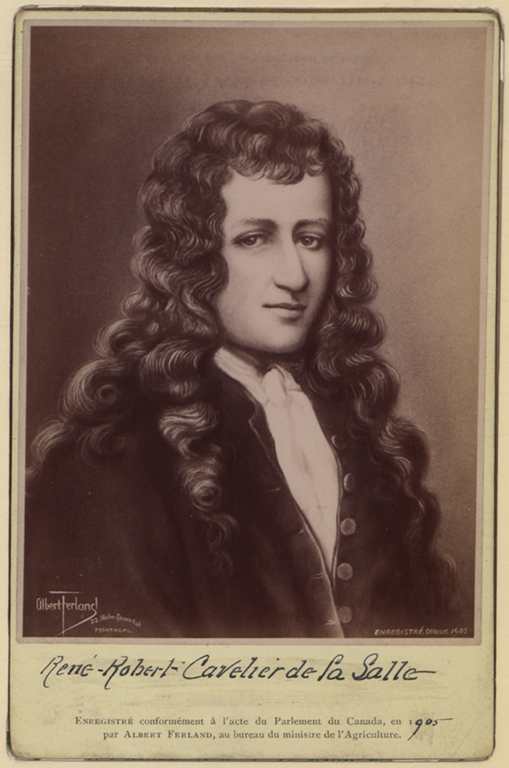

Whatever the perceptions of those involved, the King of Spain ultimately wanted New Mexico to remain as part of the empire due to geopolitical concerns. Carlos II issued the official order to resettle the colony in 1683, a full century following the initial settlement decree issued by Felipe II. Due to increased Apache raiding, Spanish officials believed that a buffer colony in the far north was more important than ever in order to protect the silver mines of Nueva Vizcaya and Zacatecas. Also, in 1682 French explorer René Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle successfully navigated the Mississippi River and laid claim to the delta region in the name of Louis XIV. The new French claim effectively drove a wedge between Spanish Florida and New Mexico, the two northernmost colonies of New Spain. Formerly imagined threats to Spain’s territorial claims all of a sudden became a reality, especially because La Salle pitched to Louis XIV the prospect of using the Mississippi River Valley as a springboard from which to invade New Spain. According to the French explorer, local native peoples would back the French due to their “deadly hatred for the Spaniards because they enslave them.”4

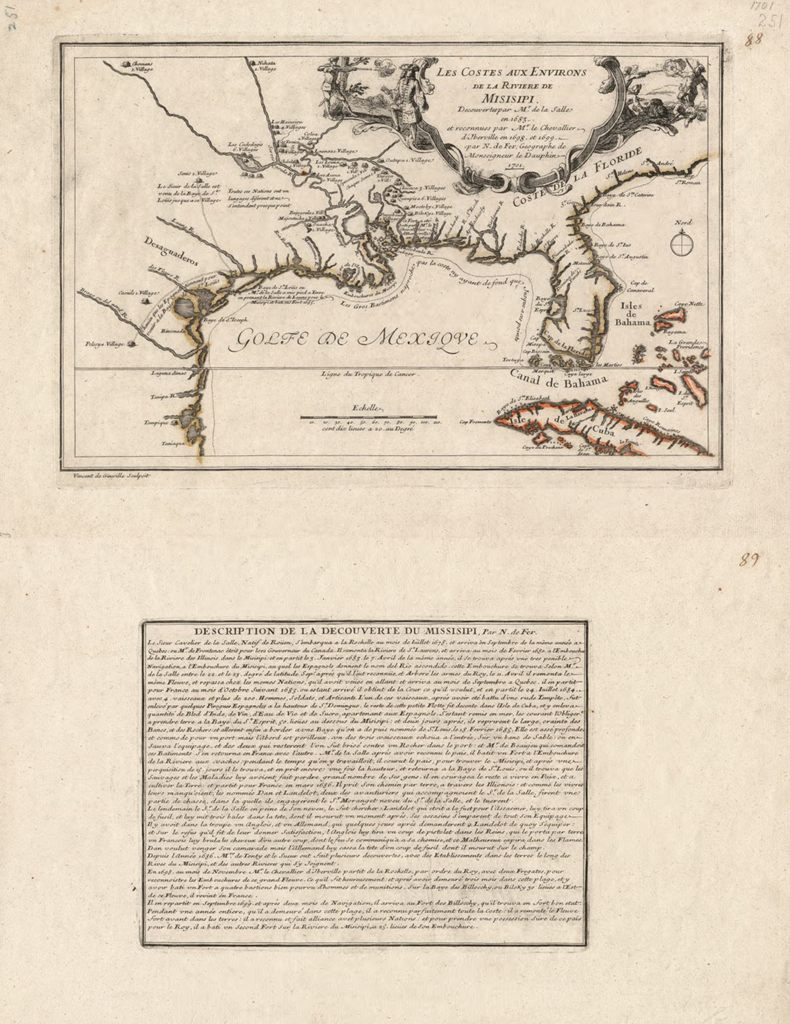

La Salle’s Cartography

In 1682, La Salle sailed down the Mississippi River, claiming all the land that he could see in the name of King Louis XIV of France. His attempt to bring French settlers to Louisiana ended in his own death in 1687, but Spanish authorities feared the incursion of French colonists not far to the east of the New Mexico colony.

These two maps illustrate the advances in cartography over the centuries. René Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle did not have the same types of technologies for map making as us. As a result, some maps displayed exaggerated or underrepresented areas. Starting in 1787, the modern theodolite, a precision surveying tools that measured angles in both horizontal and vertical planes, helped mapmakers create much more reliable maps.

A modern map of La Salle’s journey produced with data gathered by satellites.

New Mexico’s vital role as a buffer zone in the geographic imagination of royal officials dovetailed with the El Paso refugees’ desire to take back their former homes and to restore their honor. They had the distinction of being the only European people to have been forced to abandon a colony by its indigenous inhabitants. After Otermín’s efforts to salvage his own legacy failed, his successors made a few equally futile attempts to reestablish Spanish rule in Santa Fe. In 1687, for example, Governor Pedro Reneros de Posada led an expedition to Santa Ana Pueblo. His forces razed the pueblo, but returned to El Paso without reclaiming the former colonial capital.

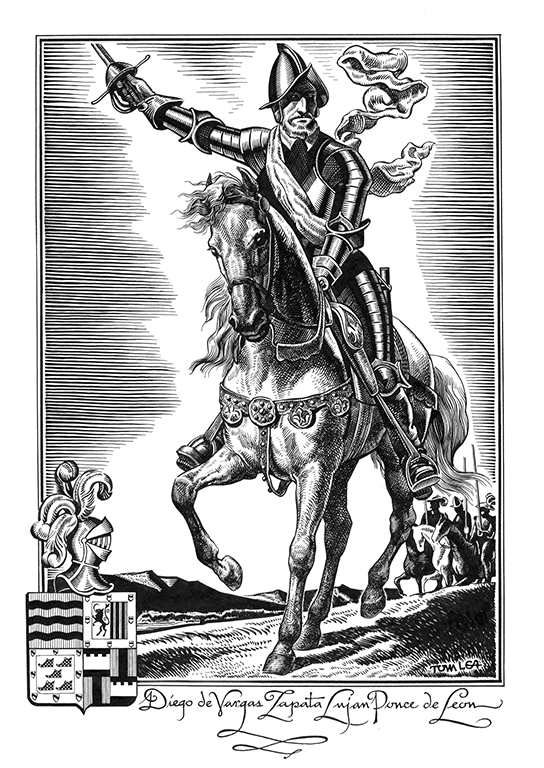

The following year, in exchange for a payment of 2,500 pesos, Diego de Vargas received the royal commission to become the next governor of the colony in exile. Preparations and travel time delayed his arrival at his new post in El Paso until February of 1691. Vargas was similar to Juan de Oñate in that he was very much a traditional conquistador in an era that no longer welcomed the former violence of conquest. Unlike Oñate, however, Vargas was more calculated and shrewd in his use of brutality and threats of violence. Vargas came to New Mexico at the age of forty-eight. A native of Madrid, he was raised by his grandmother and eventually left his wife and five children behind in Iberia in order to settle his father’s affairs in the Americas. Much like other noblemen, he possessed large tracts of land but very little liquid wealth. His time in the Americas did little to resolve that situation, although he served admirably in administrative posts in Oaxaca and Michoacán in southern New Spain. He hoped to enhance his family name and his personal fortune through service as New Mexico’s governor. First, however, he would have to reconquer the province.

Almost immediately after his arrival in El Paso, Vargas began to organize a reconnaissance mission of the Pueblo heartland. In the fall of 1692, he made his first foray northward along the Rio Grande with a small, but concentrated force of about sixty soldiers and one hundred indios amigos: Piros from Senecu and Socorro and Isleta people, comprised the bulk of the native allies. In his mind’s eye, he imagined precisely how the reconquest was to proceed. Vargas intended to retake the colony without so much as firing a single shot. As his group approached each Pueblo, they intentionally kept their weapons holstered. The first move was to simply announce their presence and then invite the Pueblo people to return to Spanish rule and the Catholic faith. Once the people consented, the Franciscans who also accompanied the mission would hear the natives’ confessions and baptize any children born during the Spaniards’ absence. Despite such principled hopes for the reconquest, all of the men in the expedition were armed and the group brought two cannons at its rear guard. Vargas understood that most Pueblos did not welcome the idea of their return.

As the group moved northward, they encountered numerous abandoned Pueblos. Due to the continuation of drought and famine, Apache raiding only intensified in the years between 1680 and 1692. Their skillful use of horses meant that the raids were swift and precise. Entire villages were deserted when Pueblo peoples attempted to find more defensible positions against the raids. Many also moved in search of more regular access to water. Due to these stresses, by the time of Vargas’ entry into the area, unity between the different Pueblo groups had all but evaporated.

Despite his ability to galvanize Pueblo resistance, Po’pay’s leadership style provides a good lens through which to consider the reasons that cooperation failed to outlive the revolt. In certain ways, he was willing to be just as brutal as the Spaniards had been. He reportedly orchestrated the murder of his son-in-law, Bua, to maintain the revolt’s secrecy. Once successful, he ordered Pueblo peoples to abandon all aspects of their lives that had come to New Mexico with the Spanish. He went so far as to tell them to stop using their Catholic names and to divorce spouses they had married under Franciscan authority. He also wanted them to give up firearms, horses, watermelons, cattle, and any other material items that had not existed in the Pueblo world before the Europeans’ arrival. Paradoxically, he also utilized syncretic religious concepts as a justification for his mandates. In his campaign against all things European, he claimed a connection to the trinity as well as to the devil, yet those concepts had not existed in the Pueblo world prior to 1540.

La Entrada de Diego de Vargas

Most Pueblo people found Po’pay’s directives to be extreme. As was the case for the Spanish refugees, by 1680 very few of them remembered a time before Spanish colonization. They relied on the tools, implements, animals, and seeds that Europeans had introduced to the region, and they saw no reason to abandon them. Indeed, as we saw in Chapter 4, acculturation and the use of Spanish technology were factors in the success of the Pueblo Revolt. Opposition to Po’pay’s leadership style, as well as differences in terms of how to reestablish each Pueblo’s traditional political, religious, and familial structures meant that by 1692 the various Pueblo groups had once again divided.

Isleta and Piro peoples had accompanied the Spanish during their retreat to El Paso, and more Isletas joined the refugees following Otermín’s failed reconquest venture. Some Pueblos reportedly welcomed the Spaniards’ return, if with trepidation. These people faced the harsh reality of continued famine and Apache raids without the advantage of European weapons and goods. By the early 1690s, their supplies of ammunition had dwindled to nearly nothing and, at any rate, the weapons had not allowed them to permanently repel nomadic raids. This group did not forget the abuses and excesses of the colonial past, but they apparently began to consider the Spanish presence preferable to their current situation.

One such Pueblo supporter accompanied the Vargas party as they made their way northward to Santa Fe. Their Zia informant, Bartolomé de Ojeda, decided to accompany the Spaniards back to El Paso following a 1689 excursion into the Pueblo world led by another governor in absentia, Domingo Jironza Pétriz de Cruzate. Jironza’s forces wrought havoc in Ojeda’s home of Zia, forcing most of its residents to take refuge at a site to the west of present-day Jemez Pueblo. Ojeda himself had participated in the Pueblo Revolt and the early resistance to the return of the Spaniards under Otermín and Jironza. In the course of battle, he was gravely wounded and left for dead. He survived and the Spaniards took him to El Paso. Despite (or, perhaps because of) the violence, Ojeda became a valuable informant to the refugees there. Historian John L. Kessell has posited that Ojeda began to support the Spanish return to New Mexico when he decided that further resistance was futile.5 Additionally, tribal traditions hold that a group of men from Jemez, Zia, Santa Ana, San Felipe, and Pecos travelled to El Paso in late 1691 or early 1692 to speak with Governor Vargas and other officials. Their purpose was to invite the Spaniards to return.

When Vargas’ party arrived outside of Santa Fe on September 12, 1692, they had received mixed signals about Pueblo intentions toward them. The villa was occupied by a recalcitrant group of Pueblos that refused to believe that the Spaniards were who they claimed to be. Instead, they figured that Vargas’ contingent was an Apache raiding party trying to trick their way inside the city’s walls. When they were finally convinced of the group’s true identity, they made it clear that the Spaniards were not welcome to enter. Despite their resistance, they surrendered to Vargas’ demands by twilight. The twin cannons trained on the town were one of the main reasons that the Pueblos changed their minds. Governor Vargas’ method of diplomacy through intimidation seemed to pay off.

Vargas later boasted of his success in retaking New Mexico “without wasting a single ounce of powder, unsheathing a sword, or without costing the Royal Treasury a single cent.”6 His comment was a deliberate cut at the failed methods of his predecessors. After he led his men into Santa Fe, he marched the same royal banner through the streets that had been carried to New Mexico by Oñate in 1598 and then by Otermín in retreat in 1680. The Pueblos present were organized into a procession behind the banner. As they paraded around the villa, they were instructed to chant “Long Live the King” each time the standard was raised.

Once again, public performance played a central role in the Spanish act of possessing the colony. After pledging loyalty to the Crown, the Pueblos received pardon for their sins from the Franciscans who accompanied the reconnaissance party.

Over a period of four months Vargas toured the Pueblo homeland, repeating similar acts of persuasion and possession. During that time frame, just over 2,200 Pueblo people, mostly children, received Catholic baptism and twenty-three different Pueblos pledged loyalty to Spain. Despite the veneer of success, signs of trouble remained. After touring the northern Pueblos, Vargas made his way back south and then moved west to the relocated Zia Pueblo, then on to Jemez Pueblo. There, warriors greeted the Spaniards by throwing dirt in their eyes. Due to the difficult state of affairs following seven years of sustained drought, however, they were unwilling to directly challenge Vargas. When pressed about their actions, they claimed that they had accidentally hit the Spaniards with dirt in an act of rejoicing at their return.

Suspicious but hopeful, Vargas returned to El Paso before the onset of winter to organize a full-scale resettlement expedition. Had the reconquest been completed at that point, the claim that it had been enacted without the shedding of blood would have been true. In reality, however, the reconquest had yet to begin. Vargas filed the necessary paperwork with the viceroy and earnestly worked to organize families to recolonize New Mexico. By October of 1693, Vargas had enlisted a group of one-hundred soldiers, seventy families, eighteen Franciscans, and a large contingent of indios amigos for the return journey to the Pueblo homeland. According to Spanish records, twenty-seven of the settlers were of African descent. They also prepared all of the livestock that the colony would need, including two-thousand horses, one-thousand mules, and nine-hundred head of cattle. And, this time, they brought three cannons instead of two.

Vargas was disappointed by the turnout. He had envisioned a group of at least five hundred settlers, and the smaller numbers left doubts in his mind about the future status of the villa de Santa Fe and its corresponding presidio. In 1694 the colony’s numbers were boosted when Fray Francisco Farfán led a caravan of an additional seventy-six families from the mining town of Parral (in present-day southern Chihuahua) to settle in New Mexico.

The main body of settlers moved at a sluggish pace due to the cattle and supplies they transported. Vargas led an advanced party to ascertain the general mood of the Pueblos before the rest of the group arrived. The governor was dismayed to find that during his absence of nearly a year, most of the Pueblos had become openly defiant toward Spanish rule once again. Ojeda traveled with the vanguard in order to act as an emissary to Pueblo peoples. Despite the maintenance of defiant attitudes, the unity Pueblos had achieved in 1680 had lapsed. Some people understood Ojeda’s support of the Spaniards, while others resolved to prevent Vargas’ reentry into their lands.

Men, women, and children alike suffered privation and hardship as they traversed the section of the Camino Real that they dubbed the Jornada del Muerto (Dead Man’s Journey). That stretch of the trail between present-day Rincon and San Marcial departs from the Rio Grande along a more passable course that is devoid of water. By the time the settlers reached Santa Fe on December 16, 1693, they were desperate to re-enter the city. The winter was fast approaching, and they wanted to get settled before deeper cold set in. As had occurred the year previously, however, the city was occupied by Pueblo people, and, once again, they refused to allow Vargas to enter. This time the threat of cannons was not enough to make them stand down. They offered fierce resistance to Vargas and his soldiers, forcing the Spaniards to erect a more permanent camp outside the town. As the group weathered the cold and snow over the next two weeks, twenty-one children died.

Jornada del Muerto

On December 30 the Spaniards initiated a relatively one-sided battle due to their superior weapons and artillery. Dwindling supplies and the toll of sustained drought left the Pueblos unable to mount an effective defense. Even with such advantages, however, Vargas was still forced to order a siege of Santa Fe to pressure the Pueblos to surrender. After a period of only a few days the Pueblos could no longer hold out. In the course of the various battles eighty-one Pueblos were killed. Another seventy were summarily executed by order of the governor as a show of Spanish might, and four hundred others were placed in captivity. Even though the capital city was back in the hands of the colonists, outlying areas had yet to submit to Spanish rule. Vargas’ dream of a bloodless reconquest was not to be.

“The reconquest would neither be bloodless nor quick.”

Over the next few years, Vargas led numerous military expeditions against various Pueblo peoples in order to assert his authority over New Mexico. Between 1693 and 1696, he realized that the reconquest would neither be bloodless nor quick. Instead, it was a slow and arduous process of warfare and negotiation. In many ways, Vargas’ efforts mirrored earlier patterns of Spanish conquest despite his intentions to deviate from them. As in the earlier episodes, the reconquest of New Mexico would not have been possible without Pueblo allies. Despite the presence of Franciscans and the desire to “pacify” the Pueblos rather than conquer them, violent action was necessary. And, in a step that could have arguably been avoided, Vargas used display violence in order to make an object lesson of Pueblo holdouts at Santa Fe.

It was perhaps no wonder that other Pueblo groups defied Spanish authority for as long as they possibly could. For a full nine months in 1694, northern Tiwa and Tewa groups allied with the Jemez people continually raided Santa Fe from their base at San Ildefonso. In the midst of such activity, disputes between some Pueblo peoples erupted into open hostility. Clashes between the Jemez people and their Keresan neighbors at Zia and Santa Ana intensified due to the Keresans’ renewed alliance with the Spaniards. In an effort to quell the dispute, Vargas personally visited Jemez in the company of several Franciscans. Despite superficially friendly relations and the baptism of over one hundred Jemez children, raids on the Keresans’ livestock continued. In mid-1694, following a raid in which four Zias and one Jemez man were killed, Vargas led a combined force comprised of 120 Spanish soldiers supported by Zia, San Felipe, and Santa Ana warriors against the Jemez people. Despite hopes for a rapid victory, the combined Spanish-Pueblo force only subdued Jemez after a frantic and bloody battle.

When the dust settled, eighty-four Jemez were killed (five of that number were burned to death and another seven pushed off of cliffs) and 361 women and children taken captive. According to Jemez oral traditions, many people jumped off of nearby cliffs to avoid capture. Not long thereafter, the image of San Diego materialized on one of the cliff faces. To this day, the likeness of San Diego is still visible on the ridges of the San Diego Mesa.

The victors remained upon the mesa for over two weeks following the battle in order to loot Jemez Pueblo and secure the captive women and children. Nearly five hundred bushels of corn were awarded the Spaniards’ Zia allies for their service. By mid-August 1694 Jemez leaders were able to negotiate the release of the prisoners. In exchange, they were to reconstruct the mission church at Jemez and join Spanish forces against Pueblos that had yet to submit to Vargas’ leadership. By September the prisoners had returned home and reconstruction began.

Saving La Conquistadora

During the Pueblo Revolt, Spanish survivors managed to rescue the wooden statue of La Conquistadora, originally brought to Santa Fe in 1625, seen here in the Cathedral.

Several northern Tewa peoples, including San Ildefonso, as well as the Zuni and Acoma people, remained opposed to the Spanish reoccupation of their homeland. By 1695, Fray Francisco de Jesús María Casano was appointed as the parish priest for Jemez at the newly reconstructed mission church. Despite efforts to maintain peace, on June 4, 1696, Jemez people rose against Fray Francisco and killed him. On that same day, several Tewa Pueblos as well as Zuni, and Acoma opened hostilities once again against the Spaniards. At San Cristóbal Pueblo and San Ildefonso Pueblo the mission friars also met their deaths. Widespread revolt continued until the end of July in what some scholars have termed a second Pueblo Revolt. The unrest is more appropriately understood, however, as a continuation of the reconquest.

In exchange for his successful reassertion of Spanish authority in New Mexico, Diego de Vargas hoped to receive the post of governor for life. Conflicts with the Santa Fe cabildo (or town council) and political intrigues required him to make his case before the viceroy and the king. By 1703, he had been reinstated as governor but he died shortly after his return to New Mexico. To honor his memory and foster a sense of community and cooperation, New Mexico officials initiated the Santa Fe Fiesta in 1712. Since that time, historical memories of the reconquest have split in two. The reconquest is both a historical event and an invention of the organizers of the annual Santa Fe Fiesta. The Fiesta was intended to provide Pueblo and Hispano residents of the colony with a point of convergence and unity. In doing so, its festivities ignored the violence and bloodshed of the years of conflict that characterized the reconquest between 1693 and 1696.

In the summer of 1696, Vargas engaged in a war of attrition with the aid of Pueblo allies. Spanish forces besieged those Pueblos that refused to recognize their authority, burning their lands and homes. Once again, Vargas relied on traditional patterns of conquest as he used existing conflicts between Pueblo groups to his advantage. By the end of 1696, most Pueblos except for Acoma, Zuni, and Hopi had once again submitted to Spanish authority. Luis de Tupatú led the people of Picuris to El Cuartelejo, an Apache ranchería (encampment) in order to elude submission to Vargas’ leadership. Additionally, the people of Sandia relocated to the Hopi village of Payupki until 1742 when Padre Menchero worked to secure their return to their homeland, secured by a royal land grant. And Tano Pueblos from San Cristóbal and San Lázaro occupied La Cañada, a site later elevated to La Villa de Santa Cruz de La Cañada. A large body of Jemez people also refused to accept Vargas’ leadership and they fled their homes to join Navajo communities to the northwest. Many scholars believe that it was at that time that Navajo women learned the practice of weaving from the Jemez refugees. The Hopi people were the only ones able to retain their autonomy until the American period.

Establishing a New Villa Santa Cruz de la Cañada was the second officially sanctioned villa in the New Mexico colony. In 1695, forty-four families from Santa Fe moved north to the Española Valley, where they established the new villa

Once the long and drawn-out reconquest efforts finally came to a close in the late 1690s, none of the factions involved had fully achieved what they had hoped. Vargas was unable to maintain his dream of a peaceful, bloodless reconquest of New Mexico and the overall Pueblo population was further reduced through his actions. The Spaniards did learn some valuable lessons during the period between 1680 and 1692, however. Never again did they attempt to reinstate the onerous encomienda system, although repartimiento and the practice of rescate (trade for native captives) did continue in altered forms. Franciscans no longer sought to annihilate Pueblo traditions, instead contenting themselves with the syncretic or compartmentalized religious practice with which the Pueblos themselves were comfortable. The result was 120 years of relative peace on both sides. Even with all of these concessions, it was the imposing threat of Comanche and Apache raids that forced Pueblos, Spaniards, and mestizos to come together in New Mexico. And, despite accommodations, Spanish political, economic, and religious systems dominated all others throughout the remainder of the colonial period.