What does Santa Claus have to do with marriage? Saint Nicholas was a Greek bishop who lived in the 4th century. In those times, and in many places today, dowry was needed to marry a daughter to a suitor. Dowry is paid by the bride’s family to the groom’s family. A story goes that a man with three daughters could not afford a dowry for them, and they were likely to be forced into prostitution. Santa Claus decided to do something. In order not to shame the family, he came at night and threw a bag of gold through the window for the first daughter’s dowry. The next night, he threw another bag of gold through the window for the second daughter. The father wanted to know who was helping them and so stayed up all night at the window. On the third night, Santa threw the bag of gold down the chimney to avoid being noticed. It is said that in this way, Saint Nick became the patron saint of prostitutes (although he is admittedly the patron saint of a lot of professions). Saint Nicholas is often portrayed with three golden balls representing the bags of gold. So if you celebrate Christmas, this year, remember Saint Nick and his acts of kindness.

What Is Marriage?

Marriage consists of a publicly, socially, or legally recognized relationship between partners. What makes marriage different than other formally recognized relationships is that it organizes sex, child care, inheritance, economic tasks, and social ties. The marriage ritual—the wedding— is typically marked by exchange of goods and services between families. Like language, ritual, and kinship, marriage is a cultural universal—virtually all cultures have some kind of marriage. However, the form that marriage takes differs markedly from culture to culture.

There are several general kinds of marriage, though these don’t cover the full range of possibilities that exist. Monogamy refers to having a single mate for life (and sometimes even beyond life), while serial monogamy means having one mate at a time. Serial monogamy is a pattern of marriage and divorce that many Westerners are familiar with. Polygamy is a general term meaning having more than one spouse at a time. Anthropologists usually refer to two varieties of polygamy called polygyny and polyandry. Polygyny occurs when males have more than one female spouse (gyno is the root for woman). Polyandry (andro means man) occurs when females have more than one male spouse. A particular form of polyandry is called fraternal polyandry, in which brothers share a wife.

The majority of traditional non-Western human societies permit polygyny, where men have multiple wives. This can be misleading, however, in that the majority of marriages in the world are monogamous, even where polygyny is socially and legally permitted. Polygynous marriage requires wealth to support multiple wives and their children, and not all men are wealthy enough to be able to support multiple wives and children.

As we will see, marriage can take many unexpected forms and vary greatly between cultures. In agricultural and pastoral societies, marriage is often a way to designate an heir to land, animals, or other property or rights. In forager societies, where there is little property to inherit, relationships can function to improve survivorship. Marriages with multiple partners, same-sex marriages, arranged marriages, and marriage to deceased persons are well-known and have been historically documented. Changing economics and ideas about personal happiness borne out of the Age of Enlightenment resulted in marriages based more on affection and companionship than practical matters like inheritance and offspring survival.

Polygyny

Polygyny is a form of marriage most commonly found in Africa and some Muslim countries. For example, South African political leader Nelson Mandela’s father had four wives. Politician Mitt Romney’s great-grandfather had four wives and 30 children, fleeing to Mexico when the Mormon Church outlawed the practice in 1890. Likewise, Barack Obama’s great-grandfather, Obama Opiyo of the Luo tribe of Kenya, had five wives.

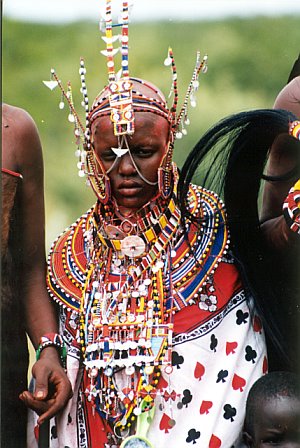

Polygyny is more common when there are differences in wealth and status among men. In traditional Maasai society of Kenya and Tanzania, women are married to older men and cannot divorce except in extreme cases. The marriages are arranged not by the couple, but by the village male elders. A woman must marry because she relies entirely on her husband for sustenance. There is no option to remain single. When a woman marries, she is given cattle, a form of wealth, to watch over, but they are not owned by her. Indeed, women cannot own anything. Instead, a woman passes along rights over cattle to her sons when they are older. A woman must have a son to inherit the cattle because when she is older she will leave her husband’s house and be taken care of by her son. If she fails to have sons, she will become reliant on the generosity of anyone who will help her.

Polyandry

Polyandry, where multiple men share a single wife, is a very rare form of marriage and is illegal in most parts of the world. This form of marriage is most commonly practiced by Tibetans in Nepal where farmland is scarce. Brothers may marry a single woman, called fraternal polyandry, to limit the number of children they have—a form of birth control.

This is important because if there are too many heirs (children that inherit), then the land will become divided and unable to support the family. The children are considered the offspring of all the brothers. In addition to preserving the estate, multiple husbands can increase the family’s standard of living by providing more paternal care, by the fathers working in the city, taking care of domesticated herds, and tending to the farm (Goldstein 1987).

Another variation on polyandry is called partible paternity. Partible paternity is practiced in lowland South America. In these systems, it is thought that the fetus is formed from the semen of more than one man. According to anthropologist Steve Beckerman, women have sex with multiple male partners to ensure that their offspring will have the best qualities of those men. When the child is born, the men acknowledge that they are one of the fathers. The men are then obligated to provide gifts like fish and meat for the child as well as provisioning for the pregnant mother. Having a “backup dad” ensures that children will have better access to food and protection from violence (Beckerman and Valentine 2002). For instance, a secondary father improves child survivorship among the Barí of Venezuela, where child mortality is high. The odds of young Barí women being widowed were so high, that men who allowed their wives to take a lover were providing a kind of insurance policy for their children (Small 2003).

Monogamy and Serial Monogamy

Marriage patterns are influenced by subsistence and economy. Monogamy is practiced in societies where family alliances are important and establishing an heir, usually male, to inherit the wealth and land is paramount. In monogamous marriages, it is not just the couple that is brought together, but also the families of the bride and groom. In these societies, divorce and extramarital affairs are severely punished as they affect the alliance and the status of not just the couple, but the two affiliated families.

Male inheritance as regulated through marriage has been very common throughout history. Historically, in Western European society, the eldest male would typically inherit the estate and women generally could not inherit. Having few other options, women had to marry, much like Maasai women, to survive. The premise of the PBS series Downton Abbey set in England in the early 1900s revolves around this very problem. Lady Mary cannot inherit her father’s estate and so a marriage with her third cousin is arranged to pass along the wealth. Oftentimes, first or second cousin marriage was ideal because this allowed the estate to be kept within the family, and titles were retained. The television program prompted a bill, the “Downton Law”, requiring equal inheritance for titles for males and females (it didn’t pass). Because so much depends on the success of marriage, divorce, especially for the wife, is difficult.

Serial monogamy (one legal spouse at a time) is very common among foragers and industrialized nations. In both cases, people tend to move to resources whether it’s a job or a mongongo nut grove in the Kalahari Desert. Less emphasis is placed on family alliances and inheritance, and so permanent marriage bonds become less important and carry fewer economic consequences. In mainstream American culture, once women entered the workforce in significant numbers, they were better able to provide for themselves and their children, and divorce, while still scandalous at the time, became increasingly possible. While some see divorce as a sign of moral decline, divorce is connected strongly to economic patterns. Divorce in general is correlated with women’s economic security.

Other Forms of Marriage

In Sudan, there is a practice called Nuer woman-woman marriage. If a man has no son, and therefore no heir, his daughter may take a female bride. The bride then chooses a man to have sex with, like a sperm donor, and the children of that union are considered the offspring of the female husband and the female wife. The female wife can also help with household chores. This union, while not a sexual one, ensures the continuation of the family name, established a cooperative economic unit, and provides an heir for the family’s wealth. Again, we see that marriage is an arrangement for purely practical reasons, in this case, the establishment of a suitable heir to the property. In this case, marriage does not regulate sex, but rather organizes family inheritance, economics, and child care.

Another Nuer practice is ghost marriage. If a Nuer woman is widowed, her husband’s brother may step in as a substitute. This system where the brother steps in and marries his brother’s widow is called the levirate. The woman, however, is still officially married to her deceased husband (the “ghost”), and any children produced by her and her husband’s brother are considered the offspring of her deceased husband. Nuer women traditionally have no significant wealth—it belongs solely to their husbands. By substituting her husband’s brother for her deceased husband, she can hold onto her husband’s wealth and pass it along to her sons when they mature. Again, we see that the marriage organizes child care and inheritance of wealth. The sororate is a similar system where the widower man marries his dead wife’s sister. This system is not unknown in Western societies. For instance, surrealist artist Salvador Dali’s father married his deceased wife’s sister making his aunt his step-mother.

Walking Marriages are practiced in the Mosuo culture of southern China. The people raise crops and livestock and live in large extended families. The families are matrilineal, meaning that inheritance flows through the female line. And so, women do not move out of their birth family (natal family) as they often do in patrilineal societies. Instead, a young woman will invite a man to come to her bedroom at night. He then leaves in the morning and has little to do with supporting his children. Instead, it is the female’s extended family, especially the woman’s brothers support her children. These unions are often referred to as walking marriages because the man walks to the woman’s house. Women may have multiple partners throughout their life, but often the couple forms a long-term relationship. Mosuo women also do much of the labor and the most important person in the household is the grandmother. One Mosuo woman describes Mosuo culture as “the most progressive in the world.” This lies in stark contrast to other parts of China where a woman must marry before the age of thirty. Women not married by this time are called “leftover” and their Shanghai parents sometimes advertise their daughters on umbrellas at a place called the “matchmaking corner.”

Arranged Marriages

The system that mainstream Americans practice where we can choose our mates is unusual among the world’s cultures. In traditional societies, marriages were arranged by parents, families, or male elders, with the bride and groom having little say in the matter. These marriages are of course called arranged marriages, a practice which continues today in many cultures and countries. This practice has roots in European as well, where the groom asks the woman’s father for his consent.

Arranged marriages often affect not just the people in the marriage, but their families as well. This is because jobs, houses, and social circles are gained through family connections bonded through marriage. In her article “Arranging a Marriage in India,” anthropologist Serena Nanda found that young women were largely accepting of the idea of arranged marriage. One young woman explained, “My marriage is too important to be arranged by such an inexperienced person as myself.”

When marriages are arranged, it is also common practice for the bride to move into the house of the husband’s family and leave her natal family. This is called patrilocal residence. In mainstream American culture, the newlyweds often live apart from their natal families in a practice called neolocal residence. Because of the wage labor economy, the couple often moves far away from their natal families. Rather than rely on family alliances for jobs and social networks, the newlyweds form their own path.

In arranged marriages, a dowry is often transferred from the bride’s family to the groom’s family. Dowries can include things like cash, jewelry, appliances, and even furniture. Dowries typically occur in stratified societies in which women can marry above their status if their dowry is sufficient. The better the dowry, the better the match a woman can make, at least in economic terms. In theory, a dowry is a way to ensure that one’s daughter is financially supported in her new home. In India, dowry can lead to harassment, burning, and dowry death. Because of patrilocal residence, brides are more vulnerable to abuse in the groom’s house, not having the protection of her natal family. Brides have been harassed to extort more dowry from her family. “Bride burning” also occurs where the woman is intentionally burned by the groom’s family and later is disguised as an accident. Sometimes the family claims that the bride committed suicide by poison or some other means, and sometimes the abuse leads to suicide. In addition, girls are sometimes seen as a financial burden that they are neglected or killed before birth. One study found that when gold prices increased, infant girls were less likely to survive (Ratcliffe 2018). As a result of the problem, compulsory dowries were outlawed in India by the Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961. And yet, the practice continues. In 2010, there were more than 8,000 cases of dowry death reported in India.

In other cultures, there are prenuptial agreements to protect brides financially in the case of death or divorce. The ketubah is a Jewish tradition that outlines the responsibilities of the groom toward his bride and includes financial contingencies in the case of divorce. Today, ketubah not only acts as a prenuptial agreement but is also a kind of decoration as well as a symbol of commitment (Sheinbaum 2019).

Bridewealth is a gift or money from the groom’s family or descent group to the bride’s family. There are various forms of bridewealth. In one form, bridewealth is compensation for the work that women do for the household. That is, the bride’s family demands payment for the work the bride would have done for the family as well as the children she would produce. Among the Igbo, bridewealth is seen as payment for the rights over children. If a woman is unable to have children the bridewealth must be returned. Alternatively, bridewealth is sometimes seen as compensation for the time and energy it took to raise the girl to a woman.

In another form of bridewealth, a groom’s elders—fathers, uncles, and older brothers—help him assemble a standardized amount of wealth to obtain a bride. The groom must then devote time and energy to his seniors instead of his wife. The arrangers of the marriage then get benefits beyond marriage alliances or the organization of inheritance. In this gerontocratic society, where older males hold all the power, younger males become indebted to older males.

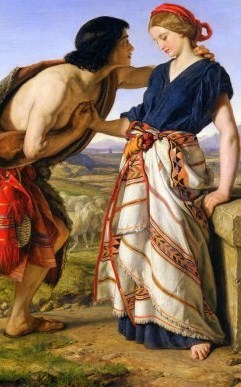

Brideservice involves the groom serving the wife’s family for several years. In the Biblical story of Jacob and Rachel (his first cousin), Jacob works for several years for the right to marry Rachel. After seven years of service, a veiled Leah is substituted for Rachel at the wedding. The sisters’ father, Laban, indicates that Jacob can marry Rachel for another seven years of brideservice. When Rachel cannot bear children, she has her handmaiden sleep with Jacob to act as a surrogate and produce children for her. This is similar to the Maasai women giving away their children so that women with none will be able to raise children.

Child Marriage

Child marriage is a very common form of arranged marriage. Where the competition to find suitable mates is intense, child betrothals can take place. Child betrothals occur when young children are promised in marriage to be consummated when they mature. This practice ensures a match early in life. Mohandas “Mahatma” Gandhi, born in 1869, was married at the age of 13 in a match arranged by his parents. Child betrothals and child marriage, especially for girls, continue today in many parts of the world including Africa, Asia, and Central Asia.

Parents sometimes give away their daughters to older foreigners and sell their daughters to repay debts (Motley 2014). Activist Memory Banda describes in her TED talk how young Malawian girls are sent to initiation camps, where they are taught to please men and sometimes get pregnant. One initiate Grace Mwase explained, “They taught us only how you can handle a man. So you should be dancing for the man. The man should be on top of you and you should be dancing for him, making him happy” (Ahmed 2014). Sometimes men called “hyenas” are paid to have sex with the girls. Sexually transmitted diseases and complicated pregnancies can result. Often people are secretive about the initiation rites because they do not want outside interference or judgment from missionaries. Yet, there is a movement of change from within. The Girls Empowerment Network encourages girls not to have sex during the initiation and to stay in school. Memory Banda has worked to end these practices in her home country of Malawi and successfully lobbied to amend the constitution to raise the legal age of marriage to 18. In Zambia, girls produced a song called “We are Girls, Not Brides” to bring attention to the problem of child marriage.

Unfortunately, child marriage is sometimes used as a way to buy a person’s labor for life–more like a form of slavery than marriage. As one Afghani girl bride explained (VOA 2018), “I kept telling them that I wanted to go to school. But my in-laws told me, ‘If you go to school, who will do the house chores? We bought you.’” There are many examples where girls are married off young and abandoned by their natal families. If they escape their marriage and try to return home, they are sent back because of the shame they are bringing to the family name.

“I kept telling them that I wanted to go to school. But my in-laws told me, ‘If you go to school, who will do the house chores? We bought you.’”

Child marriage also has health negative effects. The World Health Organization reports that childbirth and pregnancy complications are the leading cause of death for girls globally aged 15 to 19. In addition, babies of adolescents are more likely to suffer from neonatal conditions. Unfortunately, the pandemic has increased economic strain and school closures, causing an increase in the incidence of child marriage. As one sixteen-year-old girl from Cameroon recently explained (Funyuy 2020),

“My father complained [that] instead of me eating his food and occupying his space, I better get married,” Inna* told The New Humanitarian in April at her home near Ngaoundéré, in the Adamawa region. “My father told me that marriage is my ticket to heaven – not education.”

And the pressure to be married and to find a decent husband can be intense. To find a suitable husband, Maasai girls are circumcised and Mauritanian girls are force-fed 9,000 calories or more a day because fat is a sign of beauty. And in the Western world, there is intense pressure for girls to be thin to be accepted and avoid fat shaming. The Universal Declaration of Humans Rights (1948) stands in opposition to child marriage, stating, “Marriage shall be entered into only with the free and full consent of the intending spouses.” In the United States, teen marriage is associated with low education, lower wages, and higher unemployment (Dahl 2010). Teen girls who marry are 50% more likely to drop out of high school.

Traditional Marriage and Love, Actually

With the rise of industrialization, urbanization, and wage-labor economics, people became more and more independent from large extended families associated with intensive agriculture. Likewise, the significance of inheritance diminished. The concept of marriage as about companionship and love emerged from this development. With the eighteenth century’s Age of Enlightenment’s focus on individuality (captured in the Constitution’s “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness), people began marrying for more individualistic reasons and choosing their own mates.

Sometimes people, especially, politicians, will bring up the idea of traditional marriage, with the intent to restore traditional marriage in American society. In these cases, traditional marriages mean monogamy between a man and a woman. For the anthropologist, as we have seen, traditional marriage means something quite different. For anthropologists, traditional marriage conjures up practices of cousin marriage, polygamy, polygyny, partible paternity, dowry, levirate, and so forth.

As discussed, marriage regulates several things—childcare, inheritance, procreation, sex, and labor. But we have also seen that marriage takes many forms around the world. What’s more, is that definitions of what constitutes a legitimate marriage can change over time. Anthropologist Rosemary Joyce (2013) discusses Supreme arguments against same-sex marriages that took place in the United States in 2013.

The counsel against same-sex marriage proposed that marriage is about producing children, and same-sex marriages should therefore not be considered valid in the eyes of the state. Joyce points out that marriage has no “singular, stable history”, but rather takes a wide variety of forms. Ultimately, the argument against same-sex marriage failed, and it is today legal in all states in the U.S. According to the Pew Research Center (2019), 30 countries legally recognize same-sex unions including most countries in North and South America and western Europe.

Polyamory has recently received much media attention. It is not technically a marriage arrangement, but rather refers to consensual romantic relationships with more than one person. Polyamorists stress that polyamory differs from cheating because the relationships are consensual. It also sometimes goes by the unwieldy name “consensual non-monogamy”. Polyamorists argue that it is not mere promiscuity, but rather a commitment to more than one person. Polyamory seems to focus more on Western ideals of love and companionship than do traditional marriages. Polyamorists point out that there are many forms of love romantic, passionate, and companionate and they can be expressed toward different people. Philosopher Carrie Ichikawa Jenkins, who has both a husband and a boyfriend, thinks that a broader definition of love is needed (Weigel 2017). Anthropologist Barbara King suggests that polyamory is a good example of just how flexible human behavior can be (King 2017).

Lesson Quiz Here