Despite the fact that peace establishments never worked in the ways that the Spaniards had envisioned, they did succeed in creating friendlier relations with Apache peoples. The period between 1786 and 1821 was characterized by peace in the larger New Mexico region. Significantly, Comanches, Utes, Navajos, and Apaches made peace with the Spaniards in a piecemeal fashion—Anza’s efforts meant that New Mexico was at peace with various nomadic peoples. Other provinces had to manage their own relations with the nomadic peoples that surrounded them. Tejanos never forged a lasting peace like that enjoyed in New Mexico. Trade goods and even captives taken in raids on Texas continued to trickle into Taos and Pecos (although by the end of the eighteenth century, the importance of Pecos as a trade site had waned).

In New Mexico, the Bourbon Reforms, in all their local manifestations, seemed to be a great success. Along with peace with native peoples, trade restrictions had been loosened. The combined result was an increase in trade, a heightened sense of security, and cultural blossoming during the late colonial era. In this context, distinctly nuevomexicano art forms took shape. Most of this artwork was based on religious imagery, in the form of three-dimensional bultos, two-dimensional retablos, and altar screens for regional chapels. These forms of santero artistry continue to the present day.

How does Santero artistry continue today?

One of these patrons was Antonio José Ortíz, a wealthy trader who had been born in 1734. His family traced its heritage to Vargas’ reconquest, and participated in the colonial government in various capacities. Between 1790 and 1806, Ortíz established a pattern of making regular financial donations in support of Catholic artwork and chapel construction. His patronage facilitated the restoration of the Rosario Chapel in Santa Fe and the restoration of the Conquistadora Chapel and the aging church at San Miguel. Additionally, he financed the construction of his own private chapel on his hacienda near Pojoaque Pueblo. All of this work was carried out by local artisans and craftsmen and it impacted New Mexico in two important ways. First, the new and restored churches exhibited a unique nuevomexicano style and flair based in the region’s folk Catholicism. Second, the local economy grew as money and resources were reinvested in such projects.

Many local artisans were known as santeros and held in reverence by their local communities. Their ability to create sacred bultos, retablos, and altar screens set them apart as holy men. Santeros were expected to serve their communities and to set good examples of daily living. José Aragón was among the most prolific santeros of the late colonial period. He utilized a variety of color schemes and formats in his artwork, and he also ran a taller (workshop where other santeros were trained) with his brother José Rafael Aragón. Although unknown by name, the Laguna Santero was another of the most well-known artisans of the era. This artist was known for his work on the altar screen of the chapel at Laguna Pueblo.

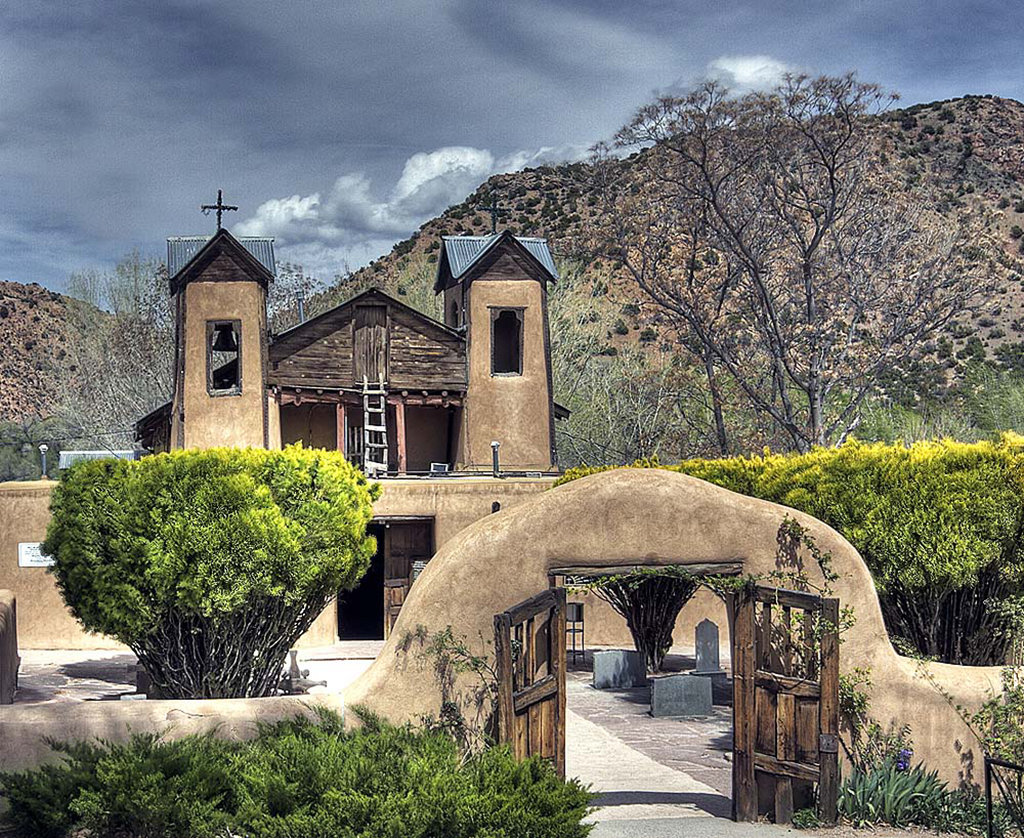

San Jose de la Laguna

At Laguna Pueblo inside San Jose Mission is an altar screen from an anonymous santero. Learn more from a National Park Service series about this piece of art as well as other New Mexico historical sites.

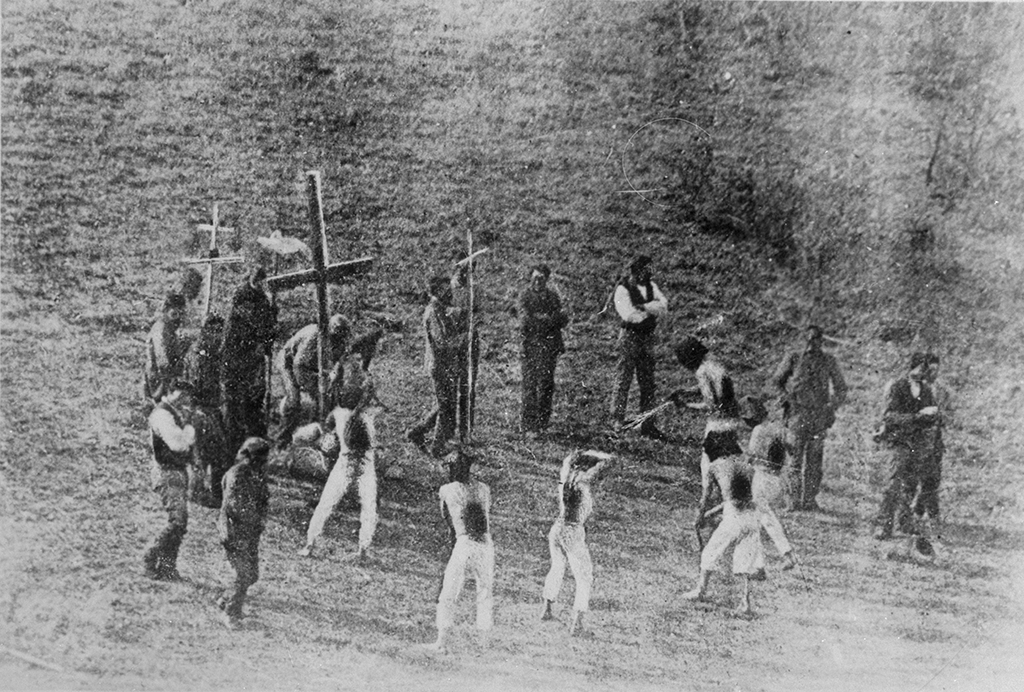

Some santeros, although not all, also participated in the Penitente Brotherhood (Hermandad de Nuestro Padre Jesús el Nazareno). This lay Catholic fraternity was created in the tradition of other such organizations that dated back to reconquest Iberia. Although there are several conflicting stories of the brotherhood’s advent in New Mexico, it is likely that Bernardo Abeyta founded the nuevomexicano Penitente order after his arrival from Durango around the turn of the nineteenth century. Abeyta is also credited with the construction of the fabled Santuario at Chimayó. Penitentes abided by their own set of bylaws and initiation ceremonies, but their main purpose was to serve their local communities and to purify themselves spiritually. Some practiced self-flagellation as part of this process. During a time frame in which Catholic leadership rarely visited New Mexico (the colony was part of the Bishopric of Durango, headquartered hundreds of miles to the south), Penitentes filled an important spiritual void in the lives of nuevomexicano Catholics.

The deeply folk-Catholic artistic traditions and cultural practices that expanded in New Mexico during the late colonial period aided in the adoption of Mexican national identity after independence in 1821. Specifically, the adoption of vecino identity allowed most nuevomexicanos to accept their place as citizens of the Mexican nation.14 Yet Mexico’s independence from Spain also created political and economic disarray in central Mexico, resulting in the breakdown of peace with nomadic peoples in New Mexico and the further isolation of the province from Mexico City. During New Mexico’s tenure as a Mexican province, its people increasingly found themselves in an untenable position between the expansionist United States and other citizens of the Mexican nation. Unique cultural forms, methods of devotion, and artistic production aided in the transition from colonial status, but were later portrayed as evidence of New Mexico’s “backward” status following the U.S. takeover of the Southwest in 1848.