The First Invasion: Texan-Santa Fe Expedition

In 1841 an ill-advised Texan expedition to Santa Fe provided Manuel Armijo with another opportunity to enhance his personal reputation for Mexican patriotism. The independent Texas Republic had hoped for annexation to the United States that was not forthcoming, and its officials also sought to make the claim that their territory stretched to the Rio Grande (called the Rio Bravo del Norte in Mexico). According to the most audacious claim (later asserted by the Polk administration following U.S. annexation), Texas not only included lands along the southern section of the Rio Grande but stretched northward to the river’s headwaters.

Had the Texan argument been legitimated, Santa Fe would have been located within Texas. Of course, nuevomexicanos and other Mexicans contested and dismissed the Texans’ territorial pursuits. Despite the secret Treaty of Velasco signed by Santa Anna after the Battle of San Jacinto in 1836, the Mexican government never recognized Texas as an independent republic. Instead, they considered it a province in rebellion. Economic complications, political infighting, and the need to fend off British and French incursions to force the payment of debts, meant that Mexican forces were never able to attempt a military reconquest. Officially, the Mexican government held that the Nueces River was the actual southern boundary of Texas.

President Mirabeau B. Lamar sidestepped the Texas Congress and commissioned a group of 270 men to travel to Santa Fe in the summer of 1841. Ostensibly, their mission was to establish trade connections. The party set out from Brushy Creek, fifteen miles north of Austin, on June 19, 1841, under the command of Colonel Hugh McLeod. Members of the debacle that became known as the Texan-Santa Fe Expedition, or the Texas Invasion of New Mexico, generally understood that the real mission was to assert possession of territory all the way to the Rio Grande boundary. A former secretary to General Sam Houston and one of the expeditionaries, Peter Gallagher, summarized the group’s purpose: “This ‘wild goose chase’ was sponsored by President Lamar for the express purpose of territorial expansion, of acquiring control of New Mexico—by peaceful means if possible; by military force if necessary.”1

Masquerading as traders along the Santa Fe-Chihuahua trail, the Texans encountered problems from the beginning. Their supplies and equipment proved insufficient for their journey, and they were unable to ward off Kiowa attacks. Due to scarcity of water and food, they plotted a circuitous route along the Brazos River, into the center of Comanche territory, westward across the Llano Estacado, and along the Red River. As they slowly attempted to traverse the 1,300-mile route, sweltering temperatures, aggravated by meager supplies, caused intense suffering. By the time they reached the Red River, they had shed most of their carts and baggage in an effort to more easily pass through thick woodlands and deep gorges.

The men were reduced to eating “frogs, lizards, roots, and ‘every living and creeping thing.'”

The last leg of the journey was a grisly nightmare as the adventurers attempted to cope with starvation, dehydration, and repeated incursions of Kiowa bands. One survivor recounted that the men were reduced to eating “frogs, lizards, roots and ‘every living and creeping thing.’”2 Another committed suicide, a few endured intense fevers, and still others were killed by Kiowa marauders.

Governor Armijo dispatched a military brigade as soon as he learned of the Texan expedition and its intentions (it had been well-publicized throughout the region). On September 17, the New Mexican force located the Texans and saved them from certain death. Lieutenant Colonel Juan Andrés Archuleta outlined their terms of surrender. First, they were to lay down their weapons. Second, Archuleta guaranteed their lives, liberty, and personal property. Third, he explained that he would escort them to San Miguel. Under the belief that there they would once again receive their weapons, the group surrendered.

Despite the Texans’ belief that they were to be taken to San Miguel and released, Governor Armijo had other plans for them. He had correctly characterized the group as an invasion force when he ordered Archuleta’s party to intercept it. At one point, he threatened to execute every member of the Texan expedition, but eventually the governor decided to hold them prisoner and transport them southward to Ciudad Chihuahua and then on to Mexico City. Along the way, many of them lost their lives. Those who were unable to walk of their own accord met execution. Others died under the harsh conditions of their long march to the Mexican capital. All along the way, compassionate locals provided the suffering Texans with water and food when possible.

n Mexico City, most of the Texas expeditionaries were held for a brief period and then released. A few were charged with treason and imprisoned at the San Lázaro leper hospital just outside the capital, the Acordada prison inside the city, or in the notorious San Juan de Ulúa prison on an island in Veracruz harbor. As historian Andrés Reséndez noted, San Juan de Ulúa “was rapidly acquiring a reputation akin to the Count of Monte Cristo’s Chateaux d’If as described by contemporary novelist Alexandre Dumas.”3 As the only tejano to accompany the expedition, José Antonio Navarro received the harshest sentence for treason. He was held for two years at the Acordada and then two more at San Juan de Ulúa. In 1845, Navarro escaped the stronghold with help from sympathetic army officers and he returned to Galveston via Havana. From Texas, he used his family’s wealth to aid the U.S. cause in the war against his former nation.

As Navarro languished in prison, Governor Armijo’s star ascended due to his harsh castigation of the Texan-Santa Fe expedition. In early November of 1841, Armijo distributed a broadside throughout New Mexico to clarify and justify his actions. He explained that it was necessary to treat the Texans harshly because their intent had been to challenge the territorial integrity of New Mexico, and by extension, the Mexican nation. Although George W. Kendall, a Louisiana newspaper man who had accompanied the expedition, published a series of scathing articles that attacked Armijo as an overly cruel barbarian, the governor received nothing but praise from his superiors and fellow citizens for his actions against the Texans.

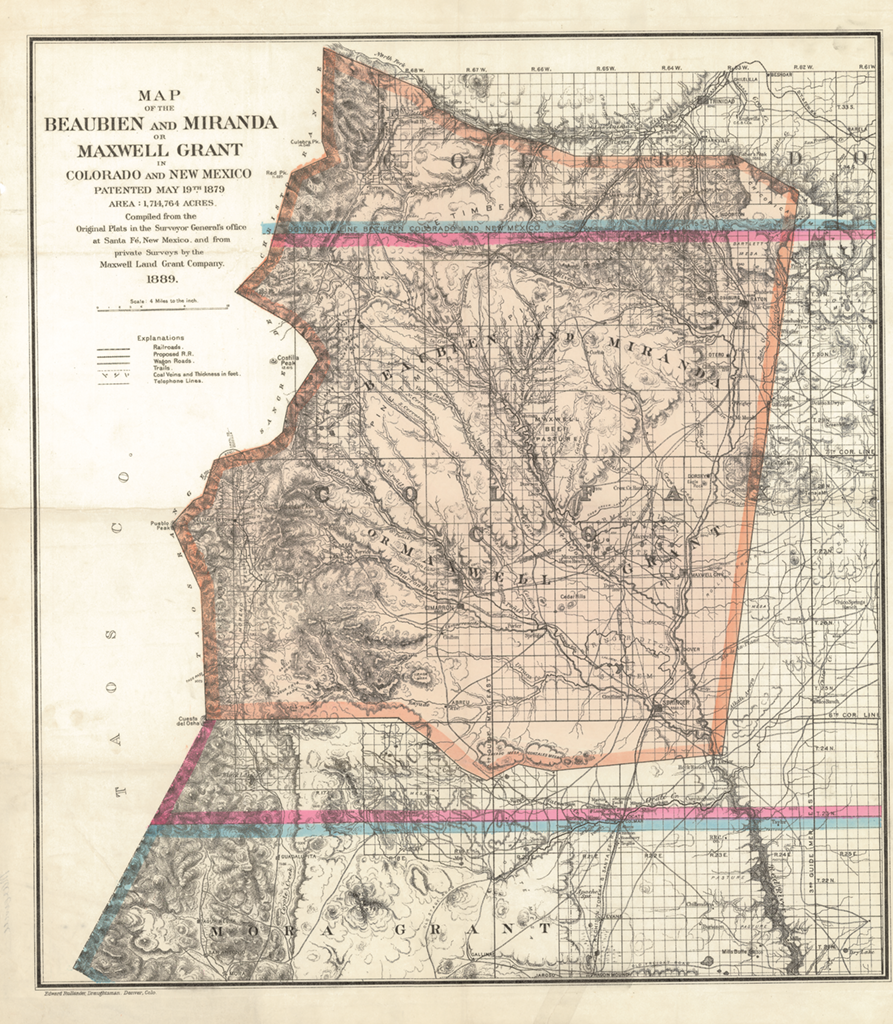

Armijo’s land-grant policies were another issue entirely. Combined with reports like Kendall’s, the critiques of his countrymen helped to weaken his strong reputation for Mexican patriotism. Especially damaging was Padre Martínez’s vocal complaint that Armijo had handed the territory over to Americans. Between 1837 and 1846, the governor granted about 16 million acres of land. The year of his successful handling of the Texan-Santa Fe Expedition, he approved the massive Maxwell Land Grant. Initially awarded to Guadalupe Miranda and Charles Beaubien, the parcel included prime lands for the cultivation of cotton, timber harvesting, cattle ranching, and prospective mining. When Beaubien’s son-in-law Lucien Maxwell took charge of the land grant, he claimed that it encompassed almost two million acres east of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains along the Cimarron and Canadian Rivers in present-day northeastern New Mexico and southeastern Colorado. Following the U.S. conquest, the Maxwell Land Grant came to symbolize the land grabbing excesses of Anglo newcomers to the region.

Such divisions among New Mexico’s people intensified when war broke out between the United States and Mexico. Those, mostly ricos, connected to the Santa Fe Trade benefitted most from the American takeover of the territory. Many of them maintained their positions of influence and authority. Poorer nuevomexicanos who already chafed under the introduction of capitalist modes of exchange had little, if anything, to gain under U.S. rule. Despite differences in economic standing, however, most nuevomexicanos resisted American occupation in one way or another.