The Human Revolution

In the previous chapters, we have discussed human features that appear in the paleoanthropological record: bipedalism, big brains, hunting, stone-tool making, fire and cooking, and even the rise of sweat glands and furlessness. We now turn to the question of when and where other humans features first appeared—storytelling, music, bodily decoration, and belief in the supernatural. That is, when, where, and why did we become truly human?

Anatomically modern humans (AMH’s) appear in the fossil record around 200,000 years ago in Africa. Evidence for the full spectrum of human behavior, however, doesn’t appear in the record until around 40,000 years ago. The shift to modern human behavior, with our interest in art, ritual, games, stories, music, language, and symbolic thought, is sometimes called the Human Revolution, the emergence of the modern human mind. The lag between physical modernity and cognitive modernity is likely due in part to problems of preservation and the sparseness of early human populations. Thus, the emergence of the modern human mind probably occurred long before we see it in the archaeological record.

The Upper Paleolithic

All people living in the Pleistocene (2.8 mya —12 kya), the last ice ages, were hunter-gatherers, living off wild non-domesticated foods. No one was farming or herding in the Pleistocene. While the philosopher Hobbes characterized the hunter-gatherer lifestyle (man in a state of nature) as “poor, nasty, brutish, and short”, life during the Pleistocene may have been one of relative abundance and health, especially compared with some later farming communities. They may have been the original, original affluent society.

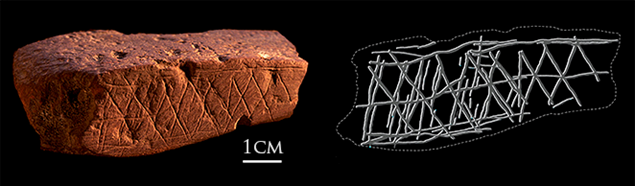

The very earliest glimmers of modern human behavior and thought occur in Africa. Fittingly, one of the earliest pieces of evidence of a modern human mind is a kind of crayon. The decorated block of red ocher, a mineral pigment, was discovered at Blombos Cave in South Africa and dates to 75,000 years ago. More recently, abalone shells filled with red ocher have been found at Blombos dating to ca. 100,000 years ago—perhaps the remains of an early artist’s palette. People were likely painting, scarring, and tattooing their bodies long before we find evidence for it in the archaeological record given the vagaries of preservation.

While the earliest examples of modern behavior occur in Africa, some of the most spectacular preservation of early modern humans occurs during an archaeological time period called the Upper Paleolithic (ca. 40 kya-12 kya), or Upper Old Stone Age, in Europe. (Note that the Upper Paleolithic describes a human time period, whereas the Pleistocene describes a geological one).

The reasons for this are several. First, modern archaeology was born in Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries. Europe was where the archaeologists were and they studied sites in that region because they were available. Secondly, there are numerous caves and rock shelters (rocky overhangs) in Europe; these are perfect containers to protect and preserve archaeological remains. Finally, environmentally, the European subcontinent was in a climate zone during the last ice age that supported vast herds of grazing animals. These animals in turn supported a relatively dense population of humans, who in turn left a plentiful archaeological record.

Several innovations become apparent in the Upper Paleolithic archaeological record that indicate the full spectrum of totally modern human mind. These include art, elaborate burial, sewn clothing, jewelry, and ritual. These are the hallmarks of modern behavior. These features indicate that these were people like us, not only in their physical appearance, but intellectually, behaviorally, and emotionally.

During the Pleistocene, Europe was inhabited by very large animals, or megafauna, including mammoths, woolly rhinos, giant cave bears, bison, along with wild horses, caribou, cattle, and lions. Upper Paleolithic people were hunting some of these animals and were reliant on terrestrial and aquatic animal protein. There is less evidence of plant consumption, though plants were likely a part of the diet as well.

Technological Innovations

Neanderthals and even Homo erectus had fairly sophisticated tools and were able to hunt and make fire. But with modern humans, there was an explosion of creativity. An innovation that became prevalent in the Upper Paleolithic was the atlatl or spear thrower. This weapon is essentially a stick that propels a long dart. This technology allowed humans to increase the force behind their weaponry as well as get some distance between themselves and their prey. The atlatls of the Upper Paleolithic were sometimes beautifully decorated with Pleistocene megafauna. The atlatl proved to be a useful weapon and its use lasted into the modern age. Spanish conquistadors, for example, encountered Aztecs equipped with obsidian-edged atlatl darts.

While “cave people” are often depicted wearing simple animal skins and furs, needles found on Upper Paleolithic sites indicate that people wore tailored clothing. Having to live and survive in the colder temperatures of the Pleistocene, people were by necessity highly skilled at making clothing from animal skin. Some figurines that date to this time also suggest sewn clothing. A series of burials at Sungir (ca. 28,000 B.P.) in Russia were covered in tens of thousands of mammoth ivory beads, which appear to have been sewn onto garments that did not survive. At other Upper Paleolithic sites dating around 25,000 BP, people were buried wearing necklaces of arctic fox teeth and shells. Like people today, Upper Paleolithic people were concerned about their appearance and very likely used symbolic markings, body decoration, and clothing to differentiate between people of different groups, just as we do today. Julia the chimpanzee may be making a fashion statement with her “grass-in-ear” behavior, but humans take personal adornment to another level.

Art and Music 1101

Einstein said “I often think in music. I live my daydreams in music. I see my life in terms of music.” The instinct to express oneself musically is very old. Early bone and ivory flutes have been found in European caves dating to 30,000 BP. Recently, a replica of one of these flutes was made, giving us a sense of what these instruments might have sounded like. Considering that these instruments were found in caves, the sound of the flutes would have been amplified by sound waves bouncing off the cave walls. Bullroarers have also been discovered in Upper Paleolithic contexts. These are instruments consisting of a thick piece of shaped wood attached to a cord. When swung in a circle, the bullroarer makes a haunting sound that can travel long distances. Historically bullroarers have been used around the world—in Australia, Ireland, North America, and elsewhere—for ceremonies and entertainment. In traditional societies, music is not just entertainment but tied to ritual. By making music together and dancing, people often develop a sense of collective effervescence and unity.

Cave Art of the Upper Paleolithic

While the first indications of decorative art occur much earlier and there are even a few possible Neanderthal examples (Davidson 2014), representational art appears for the first time in the Upper Paleolithic and equivalent time periods in Asia. In contrast to purely decorative art, representational art resembles something in the physical world. Caves of southern France and northern Spain contain images of Pleistocene horses, ibex, mammoths, rhinos, lions, bears, and even a great auk.

The most famous of these caves is Lascaux (pronounced Las-CO) in southern France dating to around 17,000 years ago. Like so many archaeological sites, it was not found by archaeologists but by curious teenagers exploring the countryside. With 600 paintings and 1,500 engravings, Lascaux contains the largest collection of ice-age art anywhere.

For that reason, and for the delicacy and beauty of the images, it was placed on the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) list of World Heritage Sites. These are cultural sites around the world that are considered to have universal value for humanity. New Mexico has two cultural sites and one natural site on the list. Can you name them?

Another famous Upper Paleolithic site, discovered by a young girl named Maria de Sautuola, is Altamira in Spain. Though Maria de Sautuola’s father argued that the paintings dated to the ice age, the site wasn’t accepted by the French archaeological establishment until French Upper Paleolithic cave art was discovered. Archaeology, as it turns out, is political. One of the panels is 45 feet in length. These panels were not one-time paintings, but “touched up” and added to with overlapping images over time. This layering effect is called a palimpsest. The term palimpsest is often used to refer to paper that has been reused, a common practice in Medieval times. Upper Paleolithic artists used the contrast between dark and light pigments (charcoal, ocher, and hematite) to create a sense of three-dimensionality. This effect is called chiaroscuro. The paintings are so surprisingly sophisticated for their time that when the Spanish artist Pablo Picasso looked upon the paintings at Lascaux he remarked, “We have invented nothing.”

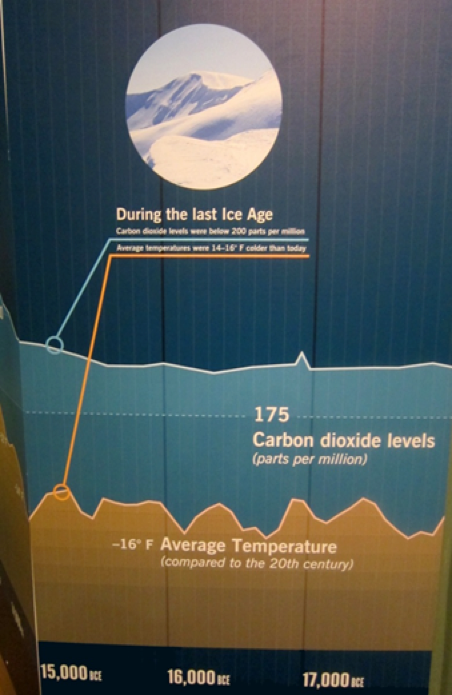

Both Lascaux and Altamira were opened to the public in the mid-1900s. Tourists, however, increased the temperature of the cave as their exhalations contained both water vapor and carbon dioxide. Carbon dioxide is of course the greenhouse gas that we are all familiar with that traps heat and causes atmospheric temperatures to rise.

Trapped inside the cave, these gasses led to a kind of “caval warming”, ripe for the growth of mold, algae, and bacteria. Both caves were closed to large numbers of visitors and they have since stabilized. Replicas of parts of both caves called Lascaux II and Altamira II have been created to give tourists a sense of the actual site.

We are so used to electricity that it is easy to forget that these were completely pitch black caves. Lascaux alone contained 150 animal fat lamps that were used to light the interiors of the caves. Remember, control of fire had occurred long before, at least by 350,000 B.P. in Europe by Neanderthals and much earlier elsewhere. The light in the cave would have flickered, perhaps giving the animals a sense of motion. One creative soul has put together overlapping images of Upper Paleolithic art that is much like a cartoon flip book, giving life and motion to these ancient creatures. That is, these images could potentially have acted as early movies, probably accompanied by that quintessentially human compunction—storytelling.

Paintings are not just located on the walls of the caves, but also the ceilings. People would have had to build some kind of scaffolding, much like Michelangelo’s work on the Sistine Chapel. Indeed, there are indentations in the walls of the caves that likely held support for the scaffolding.

Upper Paleolithic cave art sites continue to be discovered as the mouths of some of these caves have been long obscured. Chauvet Cave in France, discovered in 1994 was the subject of Werner Herzog’s film Cave of Forgotten Dreams and may be the oldest example of an Upper Paleolithic cave dating to around 35,000 years. The subject matter of the cave is also unusual, depicting dangerous animals like lions, bears, rhinos, and mammoths compared to the predominance of horses at Lascaux. Another cave called Cosquer has its opening beneath the waters of the Mediterranean. As the ice sheets of the Pleistocene melted, ocean levels rose, submerging the once-dry entrance. In the submerged portion of the cave, there are no paintings and only engravings. Presumably, the paintings have been washed away by rising sea levels. In the portion of the cave that is not submerged, there are paintings of horses, possible jellyfish, and a Great Auk, a species of penguin. Sadly, four divers died when they lost their way in the cave. It was this event that brought the cave to public attention.

Portable Art

In addition to cave art, portable art is abundant. These, of course, qualify as artifacts, being transportable from place to place. Upper Paleolithic artists excelled at depicting animals in all their earthy glory. In one instance, an herbivore (chamois) is either defecating or perhaps giving birth as a bird perches near its behind. Another very famous example of portable art is the lion-man/woman. The artifact combines both human elements (like bipedalism or walking on two legs) and lion elements, embodying the human ability to create new realities.

While portraits, or depictions of actual people, are uncommon, there are about 200 known “Venus figurines” or woman figures (Thurman 2015). (The term Venus figurine is not used in some circles to avoid assuming that the figurines represented goddesses).

These are voluptuous female bodies made from clay, ivory, and stone. There is little attention paid to the face, head, and extremities. The interest is in the body—the breasts, buttocks, and belly. Several of these figurines appear to be pregnant with an everted navel. The earliest representational art in Europe is a Venus of Hohle Fels in Germany dated to ca. 35–45 thousand years ago. There are also woman figures in cave art that use the natural topography of the cave to indicate the pregnant belly and vulva.

But what do these figures mean? Some Venus figurines, like the Venus of Hohle Fels, contain traces of red ocher, a red mineral pigment, possibly suggesting a ritual rather than functional nature. Others have suggested that the figurines are an effort to cope with the dangers of childbirth or were a fertility fetish. Still, others suggest they depict an early European goddess.

Venus figurines, however, span thousands of years and a wide area from Western Europe to Siberia. Determining the meaning of something that spans that kind of time and space is challenging. We know that symbols in our own culture can change in meaning over just a few generations, so imagine the possible varied meanings Venus figurines might have had over thousands of years.

Meaning of Upper Paleolithic Art

Some types of questions in archaeology are truly difficult to answer even with an abundance of remains. The nature of Upper Paleolithic art is one of them. There are some reasonable ideas though. Many have noticed that the horses at Lascaux are large-bodied and pregnant looking, not unlike Venus figurines, suggesting a concern with fertility or an interest in the origins of life. Several cultures have ideas about humans emerging from caves to this world, and it is possible that Upper Paleolithic people viewed caves in a similar light. In addition to depictions of robust animals, there are also very clear indications of atlatl darts flying towards animals. As mentioned, Abbe Henri Breuil argued that these images represent hunting magic, a kind of sympathetic magic where like affects like, in which symbolically killing the animals or imitating the kill helps in the actual hunt.

Other images suggest an abiding interest in seasonal changes in the animal world. One bison appears to be shedding his wool for the summer. Another image at Lascaux shows just the head of caribou, which some have argued looks like annual migrations of caribou as they cross rivers.

We know from excavating open-air sites—sites not in cave or rockshelter contexts—that Upper Paleolithic people targeted and killed caribou at vulnerable points along rivers so they would have seen these crossings. In an example of portable art on a long bone, one side of the bone depicts mating European vipers, a spring event, while the other depicts salmon, which run in the spring.

Others have argued that the caves served as a kind of temple to indoctrinate members into the group through a rite of passage. The interiors of caves were not used as living spaces, as the refuse of everyday life does not occur there, lending some support to this idea. The images, it has been argued may have served as mnemonic devices for important stories which convey the values, symbols, and ancestors of a culture. There is one famous painting in Lascaux that involves a humanoid and a bison that appears to depict a story.

Of course, some of the art might be “art for art’s sake”. Children love to paint and create for the sheer joy of creating and experimenting. Even chimpanzees have been known to paint in captivity. We know from measurements on finger traces on soft cave walls and footprints on ancient cave floors, that children were in the caves and also decorated the walls along with adults. Humans need to create, represent the world around them, and breathe meaning into symbols in a way that no other animal does. For thousands of years, we humans haven’t just lived in the world, we have created it as well.

Elaborate Burial

Another hallmark of the Upper Paleolithic is elaborate burial practices. Before this time, there is little scant or controversial evidence for ritualized burial (Sima de los Huesos and Rising Star). Again, it may be that the record simply hasn’t preserved the material traces of ritual burial and that it only becomes evident later as populations become larger and more stable. Neanderthals some 60,000 years ago buried their dead at Shanidar Cave in Iraq, but there are no grave goods, red ocher, or other indications of ritual.

Burial in the Upper Paleolithic becomes a far more elaborate affair. At Sungir, burials include one adult male and two children, who are buried head-to-head. The site dates to ca. 24,000 years ago, and the three burials include more than ten thousand ivory beads, along with mammoth ivory bracelets, beaded caps, decorated belts, ivory pendants, an ivory lance made from a straightened woolly mammoth tusk, and an animal pedant among other grave goods. Experimental archaeology often tries to replicate ancient technologies to gain insight into how tools were made, how long they took to make, and the types of skills that would have been required. Each bead, based on experimental archaeology, is thought to have taken an hour to make. The burials at Sungir indicate that Upper Paleolithic people were highly skilled artisans. Who among us today would even know where to begin to straighten an elephant tusk?

Another set of burials at a site called Dolni Vestonice in what is today the Czech Republic, like Sungir, indicate an interest in ritual and the afterlife. Three young people, two males and perhaps one female were buried together with careful positioning, perhaps a kind of visual story. The men on either side of the central figure both met violent deaths, with one having a wooden pole through his pelvis. His hands were placed on the central figure’s pelvis. The male on the right was lying on his stomach. The skeletons were covered in red ocher and fire lit atop the trio. As with the cave art and Venus figurines, several attempts have been made to interpret the meaning of this careful positioning—a birth gone wrong, human sacrifice for wrongdoing, and even evidence for homosexuality (known among some modern hunter-gatherers). Though we cannot say specifically what the burial positioning represents, it suggests an interest in what happens after death and possibly a belief in the afterlife. This behavior shows that Upper Paleolithic people were like us cognitively (mentally) and emotionally, fully capable of pondering the mysteries of life and death and acting on those beliefs with symbolic gestures.

Dog Domestication

Another important event associated with the Upper Paleolithic is dog domestication. Dogs were the first species to be domesticated by humans, plant, or animal. Dogs throughout the ages have provided much for humans including help in hunting, herding, guarding, warmth, food, hauling materials, sacrifices, and companionship. At the ice-age site of Predmosti, Moravia, a dog skull was found with a mammoth bone in its mouth suggesting dog domestication is very ancient. But what is domestication? Domestication has two meanings really, but both are defined with respect to humans. One simply means tame and friendly to humans. But it has a more technical meaning as well. Domestication means that traits are selected for by humans resulting in changes to the genome of an organism. Dogs were domesticated from wolves (Canis lupus). Some argue that wolves were kept as pets and the more docile ones bred. Others, like Ray Coppinger, disagree. Coppinger thinks that this manner of domestication was just not feasible for Paleolithic humans. Instead, he thinks more docile and “tame” wolves tended to hang around human settlements. The food these animals obtained provided them with a selective advantage, thereby allowing them to survive and reproduce at a greater rate than wolves who did not venture near human settlements. Coppinger says that in effect, dogs were self-domesticated. In this regard, dogs both experienced a change in the genome and also became more friendly to humans. Recent research has begun to pinpoint the genes that make dogs so sociable. The genetic area affected also interestingly is affected in people with Williams-Beuren Syndrome. People with this syndrome tend to be indiscriminately friendly.

What Does the Fox Say… About Domestication?

One of the most fascinating studies that reflects on dog domestication is the silver-fox experiment. In 1959, Dmitry Belyaev conducted a study on silver foxes of Siberia who were being bred for their fur. Belyaev bred the docile foxes (1% of the population) with each other, being careful not to inbreed them. After just a few generations, not only did Belyaev have very friendly, even pet-worthy foxes (though they can be unpredictable), but he noticed other morphological changes as well. The fox’s ears became floppier, their coats became patchier, their muzzles shortened, their teeth were smaller, their tails wagged, and they began to vocalize and play. In essence, they were retaining juvenile fox physical traits—called neoteny—just by selecting for friendly behavior. Other domesticated animals show similar neotenic, that is juvenile, traits in adulthood.

Something similar may have happened in dogs, whether the traits were selected by humans or a result of self-domestication. That is, dogs are essentially wolves that retain juvenile characteristics. Why are dogs so important to discuss in an anthropology class? Anthropologist Pat Shipman (2015) has argued that we humans owe dogs a lot. She proposes that it was dog domestication that allowed us to out-compete Archaic Humans like Neanderthals, who had complex tools, fire, and hunting prowess. What they lacked, she argues, was early dogs, “wolf dogs” as she calls them. Aside from companionship, dogs provide warmth, and protection, can haul items, help humans hunt, and in a pinch, can be eaten. Dogs would especially have been useful for hunting. Anthropologist Richard Lee noted that among the Bushmen, the man who owned a pack of dogs brought in 75 percent of the meat. Shipman describes humans (and their wolf dogs) as an invasive species, eventually out-competing the Archaics.

Not only do dogs provide a window into the success of early modern humans, but they might just be the key to understanding humans in a more general sense. Some scholars argue that humans, like dogs, self-domesticated. In effect, there was a selective advantage to neoteny in humans, retaining juvenile traits. Some think that it is our playful nature, our child-like curiosity that won the day over Archaic humans.

The Earliest New Mexicans

We know that people occupied Africa, the Middle East, Australia, and Asia during the Pleistocene. But what of the Western Hemisphere, the New World—a.k.a. the Americas? Were people here during the Pleistocene, or were the Americas empty continents? New Mexico, as it turns out, is famous for its pivotal role in answering this question.

Influential osteologist Aleš Hrdlička was certain that people had only been in the Americas for a few thousand years. This issue, like so many in archaeology, was not purely academic.

North American natives were depicted as relative newcomers to the Americas who cast out a former glorious “race”, who had built the earthen monuments that archaeologists encountered. You can see how this view of the recent peopling of the New World might fit nicely with the drive to colonize the American West.

The site that changed the face of American archaeology and ran directly counter to Hrdlička’s ideas is called the Folsom site of northeastern New Mexico. Like so many significant archaeological discoveries, the Folsom site was found not by an archaeologist, but by the keen eye of former slave turned cowboy, George McJunkin. Searching for lost cattle following a devastating flood near the town of Folsom in 1906, he discovered some odd-looking “cow” bones. These turned out to be a fossilized and extinct form of bison called Bison antiquus that lived during the Pleistocene.

Later, in the 1920s, excavation revealed humanly made dart points in direct association with the bison. Using the Principle of Association, it became clear that people were indeed in the Americas during the Pleistocene. The Principle of Association is that objects in the same soil layer date to the same time period. The Principle of Superposition means that older layers are at the bottom and younger ones are at the top. Other Folsom-aged sites were subsequently discovered, and Hrdlicka goes down in history as being completely wrong.

The Paleoindian Period

If you visit the New Mexico Museum of Natural History in Albuquerque, you can see a reconstruction of a Colombian mammoth, a camel, a saber cat, and dire wolves—Pleistocene mammals that were here in New Mexico. What is less obvious is the mural on the wall depicting people around a mammoth kill. In New Mexico there are numerous Paleoindian sites, referring to sites that date to the Pleistocene. Suffice it to say, people were here in the New World near the close of the Pleistocene.

The Paleoindian Period, as it’s called, is divided into segments based on changes in tools. Two Paleoindian periods are especially important. These are the Clovis period and the Folsom period, both named after towns in New Mexico.

Clovis age sites are about 13,000 years old and Folsom-aged sites are around 11,500 years old. A “Clovis site” is shorthand for “Clovis-aged site”, and refers to any site that dates to the Clovis period. The same is true for Folsom sites. Clovis-aged sites date to the time when mammoth, horses, camel, dire wolves, and other Pleistocene animals roamed North America.

Mammoth and bison, and to a lesser extent elk, were the primary targets of Clovis hunters. A distinct Clovis technology consisted of stone points that are grooved or fluted part way up the point. (Doric Greek columns are also fluted or grooved if that helps you remember the term). This fluted technology, as it is called, is unique to the Americas, and occurs nowhere else in the world. The bottom third of Clovis points are smoothed on the edges, likely because they were hafted onto an atlatl dart.

Clovis points are diagnostic of the Clovis period, meaning they were unique to this time period. If you find a Clovis point, it is on the order of 13,000 years old. It is also a very rare find. Collectors seek out Clovis points because of their rarity and also because they represent mastery in flint knapping, or making stone tools. Unfortunately, collecting these points without recording provenience information or context, strips away the information potential.

What Happened to the Big Beasts?

Clovis people lived alongside Pleistocene megafauna. But what happened to these creatures? There are two main schools of thought: climate change and human predation. There is evidence for a massive drought during Clovis times. According to a recent study by scientists at UNM, this mass extinction appears to have been caused by a drought so severe that nothing like it had occurred for at least 40,000 years that they examined. The site of Blackwater Draw in New Mexico also has the earliest human-made wells anywhere, associated with a prolonged drought during the Clovis period.

Climate-change proponents argue that vast mammoth steppe habitats of the giant grazing mammals shrank, became fragmented, and the herds eventually dwindled to extinction through lack of sufficient forage. During the extinction event, fully 3/4 of all mammalian genera (35 genera) in North America disappeared, including mammoths and mastodons, all camelids (camel species), and horses—all within 1000 years of each other. About 40 percent of small mammals like voles and other rodents, mink, martens, and weasels went extinct, as did about 40 percent of mollusk species.

Similar extinctions occurred in Europe, northern Asia, and Australia as well. Tropical areas like central Africa and south and Southeast Asia were much less affected—megafauna like elephants and rhinoceros still exist there, at least for the time being. Many larger Pleistocene mammals (including elephants in Africa) become smaller through time at the end of the Pleistocene, which is one adaptive response to a reduced food supply; this is also true of the Pleistocene bison in North America.

This massive drought in North America appears in the stratigraphy at Clovis sites and is called The Black Mat, which represents the mud at the bottom of a dried-out water source. You can see it clearly at the Murray Springs site in Arizona. Below the mat, there are mammoths, horses, and other Pleistocene megafauna, and above the mat, only bison remain. There is an informative exhibit in the New Mexico Museum of Natural History that discusses Pleistocene climate change.

Another hypothesis for the massive extinction is the overkill hypothesis. The overkill hypothesis holds that Paleoindians were hunting specialists that concentrated on a few large species which could provide a huge return in meat and fat. Evidence for megafauna specialization includes, for example, the fact that of 14 known Clovis kill sites in western and central North America, 11 contain the butchered bones of mammoth or mastodon. Archaeologist Todd Surovell argues that the number of Clovis elephant kill sites is exceptionally high if you look at elephant kill sites on a global scale. Surovell also argues that human colonization tracks mammoth extinction through human prehistory. Proponents of overkill also point to several other previously unoccupied land masses of the world where megafauna disappeared simultaneously with the colonization of humans. Australia, for example, was populated with a series of giant species of kangaroos and grazing marsupials that went extinct when humans first colonized the island-continent sometime between 40-60 kya. On Madagascar, the giant lemur Archaeoindris, about the size of a male gorilla, went extinct.

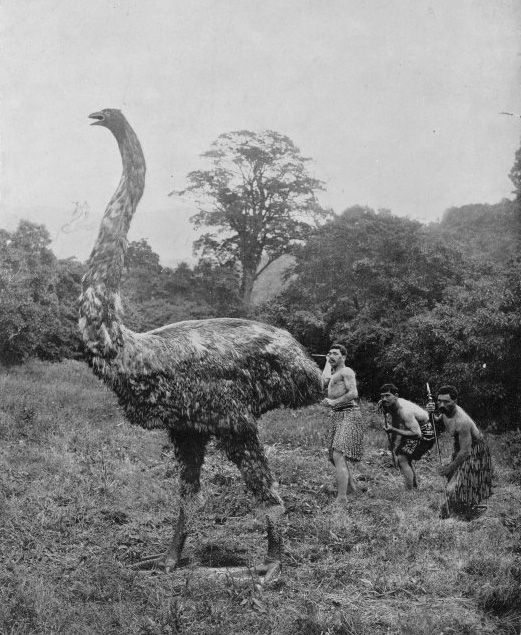

New Zealand is another case in point. Several species of giant flightless birds called moas (Dinornithiformes)—some stood up to 12 feet tall and weighed up to 500 pounds—existed on the islands before the arrival of the first humans from Polynesia around AD 1250-1300, then abruptly became extinct within 200 years of their arrival from over-hunting. One reason for the swift demise is that the native species had no defensive fear of humans and could be easily approached and killed. The overkill hypothesis is similar to Pat Shipman’s hypothesis about humans and dog companions being the invasive species that wiped out Archaic Humans. And today, we see that humans are the main threat to other primates today.

In the Americas, a combination of the two factors contributing to the demise of megafauna—climate and human predation—is quite possible. Habitat loss due to climate change would have fragmented the large, interconnected populations of steppe animals. Indeed, we know that habitat fragmentation is a key factor in species extinction today. Human hunters could have delivered the final blow by overhunting the dwindling populations of megafauna that remained.

Lesson Quiz Here