Learning Objectives

- Explain how and when schemas and attitudes do and do not change as a result of the operation of [glossary_exclude]accommodation[/glossary_exclude] and [glossary_exclude]assimilation[/glossary_exclude].

- Outline the ways that schemas are likely to be maintained through processes that create [glossary_exclude]assimilation[/glossary_exclude].

Human beings have very large brains and highly developed cognitive capacities. Thus it will come as no surprise that we meet the challenges that we face in everyday life largely by thinking about them and then planning what to do about them. Over time, people develop a huge amount of knowledge about the self, other people, social relationships, and social groups. This knowledge guides our responses to the people we interact with every day.

Schemas as Social Knowledge

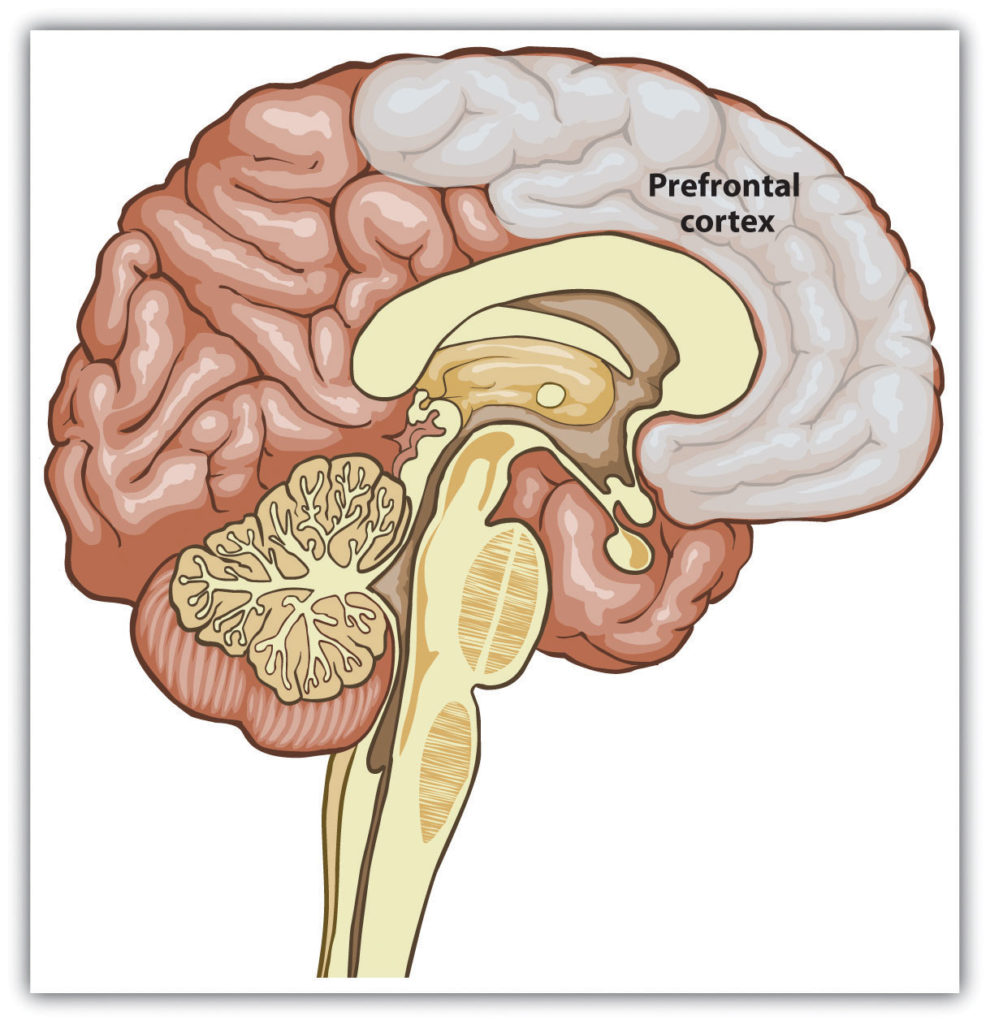

The outcome of learning is knowledge, and this knowledge is organized and stored in schemas. In the brain, our schemas reside primarily in the prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain that lies in front of the motor areas of the cortex and that helps us remember the characteristics and actions of other people, plan complex social behaviors, and coordinate our behaviors with those of others (Mitchell, Mason, Macrae, & Banaji, 2006). The prefrontal cortex is the “social” part of the brain. It is also the newest part of the brain, evolutionarily speaking, and has enlarged as the social relationships among humans have become more frequent, important, and complex. Demonstrating its importance in social behaviors, people with damage to the prefrontal cortex are likely to experience changes in social behaviors, including memory, personality, planning, and morality (Koenigs et al., 2007).

How Schemas Develop: Accommodation and Assimilation

Because they represent our past experience, and because past experience is useful for prediction, our schemas serve as expectations about future events. For instance, if you have watched Italian movies or if you have visited Italy, you might have come to the conclusion that Italians frequently gesture a lot with their hands when they talk—that they are quite expressive. This knowledge will be contained in your group schema about Italians. Therefore, when you meet someone who is Italian, or even when you meet someone who reminds you of an Italian person, you may well expect that they will gesture when they talk.

Having a database of social knowledge to draw on is obviously extremely useful. If we didn’t know or couldn’t remember anything about anyone or about anything that we had encountered in the past, our life would be difficult indeed because we would continually have to start our learning over again. Our schemas allow us to better understand people and help us make sense of information, particularly when the information is unclear or ambiguous. They also allow us to “fill in the blanks” by making guesses about what other people are probably like or probably going to do in cases where things are uncertain. Furthermore, the fact that different people have different past experiences—and thus that their schemas and attitudes are different—helps explain why different people draw different conclusions about the same events.

Once they have developed, schemas influence our subsequent learning, such that the new people and situations we encounter are interpreted and understood in terms of our existing knowledge (Piaget & Inhelder, 1966; Taylor & Crocker, 1981). Imagine, for instance, that you have a schema—and thus an expectation—that Italians are very expressive, and you now meet Bianca, who has arrived at your school directly from Rome, Italy. You immediately expect her to be outgoing and expressive. However, as you get to know Bianca, you discover that she is not at all expressive and does not “talk with her hands.” In fact, she is quite shy and reserved. How does existing information influence how we react to the new information that we receive?

One possibility is that the new information simply updates our existing expectations. We might decide, for instance, that there is more variation among Italians in terms of expressiveness than we had previously realized, and we might resolve that Italians can sometimes be very shy and thoughtful. Or perhaps we might note that although Bianca is Italian, she is also a woman. This might lead us change our schema such that we now believe that although Italian men are expressive, Italian women are not. When existing schemas change on the basis of new information, we call the process accommodation.

In other cases, however, we engage in assimilation, a process in which our existing knowledge influences new conflicting information to better fit with our existing knowledge, thus reducing the likelihood of schema change. If we used assimilation, instead of changing our expectations about Italians, we might try to reinterpret Bianca’s unexpected behavior to make it more consistent with our expectations. For instance, we might decide that Bianca’s behavior is actually more expressive than we thought it was at first, or that she is acting in a more shy and reserved manner because she is trying to impress us with her thoughtfulness or because she is not yet comfortable at the new school. Or we might assume that she is expressive at home with her family but not around us. In these cases, the process of assimilation has led us to process the new information about Bianca in a way that allows us to keep our existing expectations about Italians more generally intact.

How Schemas Maintain Themselves: The Power of Assimilation

As we have seen in our earlier discussion, accommodation (i.e., the changing of beliefs on the basis of new information) does occur—it is the process of learning itself. Our beliefs about Italians may well change through our encounters with Bianca. However, there are many factors that lead us to assimilate information to our expectations rather than to accommodate our expectations to fit new information. In fact, we can say that in most cases, once a schema is developed, it will be difficult to change it because the expectation leads us to process new information in ways that serve to strengthen it rather than to weaken it.

The tendency toward assimilation is so strong that it has substantial effects on our everyday social cognition. One outcome of assimilation is the confirmation bias—the tendency for people to favor information that confirms their expectations, regardless of whether the information is true.

Consider the results of a research study conducted by Ross, Lepper, and Hubbard (1975) that demonstrated the confirmation bias. In this research, high school students were asked to read a set of 25 pairs of cards, in which each pair supposedly contained one real and one fake suicide note. The students’ task was to examine both cards and to decide which of the two notes was written by an actual suicide victim. After the participants read each card and made their decision, the experimenter told them whether their decision was correct or incorrect. However, the feedback was not at all based on the participants’ responses. Rather, the experimenters arranged the feedback so that, on the basis of random assignment, different participants were told either that they were successful at the task (they got 24 out of 25 correct), average at the task (they got 17 out of 25 correct), or poor at the task (they got 10 out of 25 correct), regardless of their actual choices.

At this point, the experimenters stopped the experiment and completely explained to the participants what had happened, including how the feedback they had received was predetermined so that they would learn that they were either successful, average, or poor at the task. They were even shown the schedule that the experimenters had used to give them the feedback. Then the participants were asked, as a check on their reactions to the experiment, to indicate how many answers they thought they would get correct on a subsequent—and real—series of 25 card pairs.

As you can see in the following figure, the results of this experiment showed a clear tendency for expectations to be maintained in the face of information that should have discredited them. Students who had been told that they were successful at the task indicated that they thought they would get more responses correct in a real test of their ability than those who thought they were average at the task, and students who thought they were average thought they would do better than those told they were poor at the task. In short, once students had been convinced that they were either good or bad at the task, they really believed it. It then became very difficult to remove their beliefs, even by providing information that should have effectively done so.

In this demonstration of the power of assimilation, participants were given initial feedback that they were good, average, or poor on a task but then told that the feedback was entirely false. The feedback, which should have been discounted, nevertheless continued to influence participants’ estimates of how well they would do on a future task. Data are from Ross, Lepper, and Hubbard (1975).

In this demonstration of the power of assimilation, participants were given initial feedback that they were good, average, or poor on a task but then told that the feedback was entirely false. The feedback, which should have been discounted, nevertheless continued to influence participants’ estimates of how well they would do on a future task. Data are from Ross, Lepper, and Hubbard (1975).

Why do we tend to hold onto our beliefs rather than change them? One reason that our beliefs often outlive the evidence on which they are supposed to be based is that people come up with reasons to support their beliefs. People who learned that they were good at detecting real suicide notes probably thought of a lot of reasons why this might be the case—“Geez, I predicted that Suzy would break up with Billy” or “I knew that my Mom was going to be sad after I left for college”—whereas the people who learned that they were not good at the task probably thought of the opposite types of reasons—“I had no idea that Jean was going to drop out of high school.” You can see that these tendencies will produce assimilation—the interpretation of our experiences in ways that support our existing beliefs. Indeed, research has found that one way to reduce our tendencies to assimilate information into our existing belief is to explicitly force people to think about exactly the opposite belief (Anderson & Sechler, 1986).

In some cases, our existing knowledge acts to direct our attention toward information that matches our expectations and prevents us from attempting to attend to or acknowledge conflicting information (Fiske & Neuberg, 1990). To return to our example of Bianca from Rome, when we first meet her, we may immediately begin to look for signs of expressiveness in her behavior and personality. Because we expect people to confirm our expectations, we frequently respond to new people as if we already know what they are going to be like. Yaacov Trope and Erik Thompson (1997) found in their research that individuals addressed fewer questions to people about whom they already had strong expectations and that the questions they did ask were likely to confirm the expectations they already had. Because we believe that Italians are expressive, we expect to see that behavior in Bianca, we preferentially attend to information that confirms those beliefs, and we tend to ignore any dis-confirming information. The outcome is that our expectations resist change (Fazio, Ledbetter, & Towles-Schwen, 2000).

Our reliance on schemas can also make it more difficult for us to “think outside the box.” Peter Wason (1960) asked college students to determine the rule that was used to generate the numbers 2-4-6 by asking them to generate possible sequences and then telling them if those numbers followed the rule. The first guess that students made was usually “consecutive ascending even numbers,” and they then asked questions designed to confirm their hypothesis (“Does 102-104-106 fit?” “What about 434-436-438?”). Upon receiving information that those guesses did fit the rule, the students stated that the rule was “consecutive ascending even numbers.” But the students’ use of the confirmation bias led them to ask only about instances that confirmed their hypothesis and not about those that would disconfirm it. They never bothered to ask whether 1-2-3 or 3-11-200 would fit; if they had, they would have learned that the rule was not “consecutive ascending even numbers” but simply “any three ascending numbers.” Again, you can see that once we have a schema (in this case, a hypothesis), we continually retrieve that schema from memory rather than other relevant ones, leading us to act in ways that tend to confirm our beliefs.

Because expectations: influence what we attend to, they also influence what we remember. One frequent outcome is that information that confirms our expectations is more easily processed, is more easily understood, and thus has a bigger impact than does information that disconfirms our expectations. There is substantial research evidence indicating that when processing information about social groups, individuals tend to particularly remember information better that confirms their existing beliefs about those groups (Fyock & Stangor, 1994; Van Knippenberg & Dijksterhuis, 1996). If we have the (statistically erroneous) stereotype that women are bad drivers, we tend to remember the cases where we see a woman driving poorly but to forget the cases where we see a woman driving well. This of course strengthens and maintains our beliefs and produces even more assimilation. And our schemas may also be maintained because when people get together, they talk about other people in ways that tend to express and confirm existing beliefs (Ruscher & Duval, 1998; Schaller & Conway, 1999).

Darley and Gross (1983) demonstrated how schemas about social class could influence memory. In their research, they gave participants a picture and some information about a fourth-grade girl named Hannah. To activate a schema about her social class, Hannah was pictured sitting in front of a nice suburban house for one half of the participants and was pictured in front of an impoverished house in an urban area for the other half. Then the participants watched a video that showed Hannah taking an intelligence test. As the test went on, Hannah got some of the questions right and some of them wrong, but the number of correct and incorrect answers was the same in both conditions. Then the participants were asked to remember how many questions Hannah got right and wrong. Demonstrating that stereotypes had influenced memory, the participants who thought that Hannah had come from an upper-class background judged that she had gotten more correct answers than those who thought she was from a lower-class background.

This is not to say that we only remember information that matches our expectations. Sometimes we encounter information that is so extreme and so conflicting with our expectations that we cannot help but attend to and remember it (Srull & Wyer, 1989). Imagine that you have formed an impression of a good friend of yours as a very honest person. One day you discover, however, that he has taken some money from your wallet without getting your permission or even telling you. It is likely that this new information—because it is so personally involving and important—will have a dramatic effect on your perception of your friend and that you will remember it for a long time. In short, information that is either consistent with, or very inconsistent with, an existing schema or attitude is likely to be well remembered.

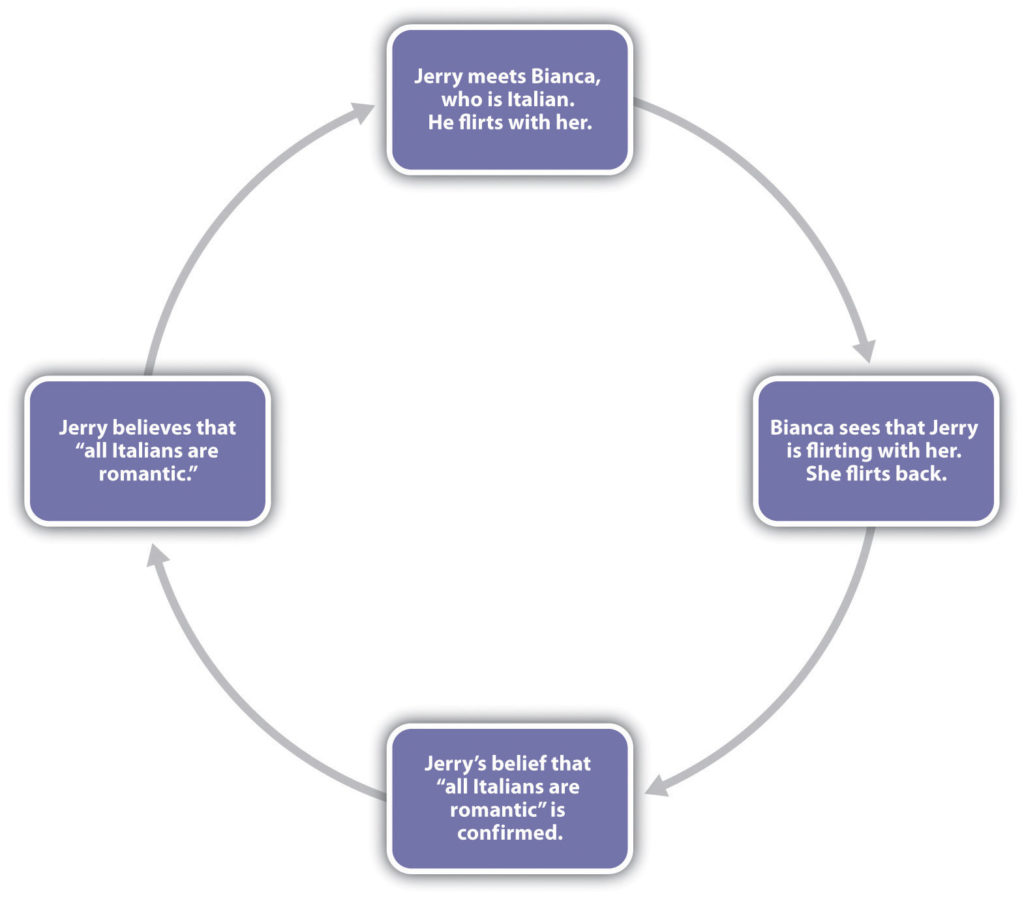

Still another way that our expectations tend to maintain themselves is by leading us to act toward others on the basis of our expectations, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy. A self-fulfilling prophecy is a process that occurs when our expectations about others lead us to behave toward those others in ways that make those expectations come true. If I have a stereotype that Italians are fun, then I may act toward Bianca in a friendly way. My friendly behavior may be reciprocated by Bianca, and if many other people also engage in the same positive behaviors with her, in the long run she may actually become a friendlier person, thus confirming our initial expectations. Of course, the opposite is also possible—if I believe that short people are boring or that women are overly emotional, my behavior toward short people and women may lead me to maintain those more negative, and probably inaccurate, beliefs as well.

We can now begin to see why an individual who initially makes a judgment that a person has engaged in a given behavior (e.g., an eyewitness who believes that they saw a given person commit a crime) will find it very difficult to change his or her mind about that decision later. Even if the individual is provided with evidence that suggests that he or she was wrong, that individual will likely assimilate that information to the existing belief. Assimilation is thus one of many factors that help account for the inaccuracy of eyewitness testimony.

Research Focus: Schemas as Energy Savers

If schemas serve in part to help us make sense of the world around us, then we should be particularly likely to use them in situations where there is a lot of information to learn about, or when we have few cognitive resources available to process information. Schemas function like energy-savers, to help us keep track of things when information processing gets complicated.

Stangor and Duan (1991) tested the hypothesis that people would be more likely to develop schemas when they had a lot of information to learn about. In the research, participants were shown information describing the behaviors of people who supposedly belonged to different social groups, although the groups were actually fictitious and were labeled only as the “red group,” the “blue group,” the “yellow group,” and the “green group.” Each group engaged in behaviors that were primarily either honest, dishonest, intelligent, or unintelligent. Then, after they had read about the groups, the participants were asked to judge the groups and to recall as much information that they had read about them as they could.

Stangor and Duan found that participants remembered more stereotype-supporting information about the groups, when they were required to learn about four different groups than when they only needed to learn about one group or two groups. This result is consistent with the idea that we use our stereotypes more when “the going gets rough”—that is, when we need to rely on them to help us make sense of new information.

Bodenhausen (1990) presented research participants with information about court cases in jury trials. Furthermore, he had obtained self-reports from the participants about whether they considered themselves to be primarily “morning people” (those who feel better and are more alert in the morning) or “evening people” (those who are more alert in the evening). Bodenhausen (1990) found that participants were more likely to make use of their stereotypes when they were judging the guilt or innocence of the individuals on trial at the time of day when the participants acknowledged that they were normally more fatigued. People who reported being most alert in the morning stereotyped more at night, and vice versa. This experiment thus provides more support for the idea that schemas—in this case, those about social groups—serve, in part, to make our lives easier and that we rely on them when we need to rely on cognitive efficiency—for instance, when we are tired.

Adapted from “Chapter 2.1: Sources of Social Knowledge” of Principles of Social Psychology, 2015, used according to creative commons CC BY-NC-SA 4.0