This Workplace Communication course takes a genre-based approach to analyze the rhetorical situation of multiple genres of workplace writing. When writing for a workplace audience, a writer must consider the audience, context, and purpose of the texts they will publish for a wider workplace audience. The following chapter outlines requirements and best practices for memos, emails, letters, and employment materials.

Memos

Technical and Report Writing describes memos as a commonly accepted method of communication within a specific business, company, or institution. The fact that memos are only used internally means they are different from letters, emails, and texting, which can be used inside and outside of the workplace. The successful operation of a company depends on memos for communication between the employees and separate departments within the company. Types of memos include: inquiries, recommendations, problem-solution, progress, and others

A memo’s format provides employees with clear and easy access to information. The message is direct and it follows a specific format for consistency. All memos includes a heading block that identifies the recipient, the sender, the date, and the subject of the message.

However, the message has three parts, each of which is identified by a specific heading. The three parts are the introduction, the body, and the conclusion. The introduction references background information and informs the purpose of the message. The body is the message, and this section can include a simple paragraph or multiple paragraphs. The conclusion expresses what the writer expects the recipient to do. The conclusion could be one paragraph or several paragraphs, or the conclusion could be a simple sentence that asks for the recipient to contact the sender if there are questions.

Memo Purpose

A memo’s purpose is often to inform, but it occasionally includes an element of persuasion or a call to action. All organizations have informal and formal communication networks. The unofficial, informal communication network within an organization is often called the grapevine, and it is often characterized by rumor, gossip, and innuendo. On the grapevine, one person may hear that someone else is going to be laid off and start passing the news around. Rumors change and transform as they are passed from person to person, and before you know it, the word is that they are shutting down your entire department.

One effective way to address informal, unofficial speculation is to spell out clearly for all employees what is going on with a particular issue. If budget cuts are a concern, then it may be wise to send a memo explaining the changes that are imminent. If a company wants employees to take action, they may also issue a memorandum. For example, on February 13, 2009, upper management at the Panasonic Corporation issued a declaration that all employees should buy at least $1,600 worth of Panasonic products. The company president noted that if everyone supported the company with purchases, it would benefit all (Lewis, 2009).

While memos do not normally include a call to action that requires personal spending, they often represent the business or organization’s interests. They may also include statements that align business and employee interest, and underscore common ground and benefit.

Memo Format

A memo has a specific format; this format includes a header that clearly indicates who sent the document and identifies the intended recipients. Pay particular attention to the title of the individual(s) in this section. Date and subject lines are also present, followed by a message that contains a declaration, a discussion, and a summary.

In a standard writing format, readers might expect to see an introduction, a body, and a conclusion. All these are present in a memo, and each part has a clear purpose. The declaration in the opening uses a declarative sentence to announce the main topic. The discussion elaborates or lists major points associated with the topic, and the conclusion serves as a summary.

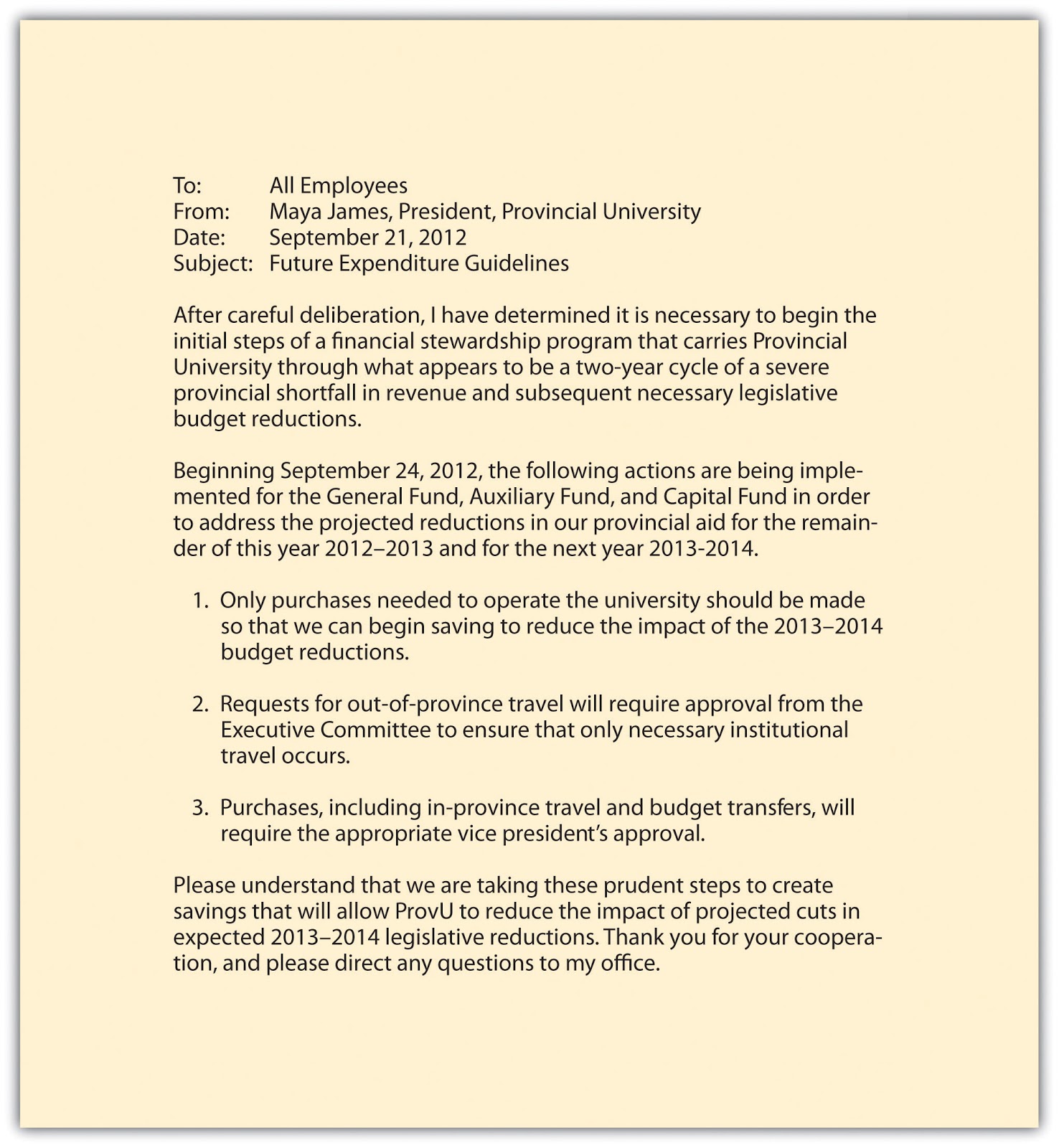

Let’s examine a sample memo.

Five Tips for Effective Business Memos

Audience Orientation

Always consider the audience and their needs when preparing a memo. An acronym or abbreviation that is known to management may not be known by all the employees of the organization, and if the memo is to be posted and distributed within the organization, the goal is clear and concise communication at all levels with no ambiguity.

Professional, Formal Tone

Memos are often announcements, and the person sending the memo speaks for a part or all of the organization. While it may contain a request for feedback, the announcement itself is linear, from the organization to the employees. The memo may have legal standing as it often reflects policies or procedures, and may reference an existing or new policy in the employee manual, for example.

Subject Emphasis

The subject is normally declared in the subject line and should be clear and concise. If the memo is announcing the observance of a holiday, for example, the specific holiday should be named in the subject line—for example, use “Thanksgiving weekend schedule” rather than “holiday observance”.

Direct Format

Some written business communication allows for a choice between direct and indirect formats, but memorandums are always direct. The purpose is clearly announced.

Objectivity

Memos are a place for just the facts, and should have an objective tone without personal bias, preference, or interest on display. Avoid subjectivity.

The following scenario provides examples of how different types of memos are utilized in a real world situation: You are a consultant for a construction company. The project manager of the company has charged you with following the progress of a job that the company has contracted. To keep the project manager informed of the progress of the job, you may send him/her one of three types of memos: A Projection Analysis Timeline Memo, which is sent before the job begins and details the expected beginning and ending dates of the job; a Progress Memo, which is sent during the progression of the job and details the progress of the job, and a Period Report Memo, which is sent after the completion of the job and details the completion dates of all phases of the job.

Emails

Electronic mail, usually called email, is quite familiar to most students and workers. It may be used like text, or synchronous chat, and it can be delivered to a cell phone. In business, it has largely replaced print hard copy letters for external (outside the company) correspondence, as well as taking the place of memos for internal (within the company) communication. Email can be useful for messages that have slightly more content than a text message, but it is still best used for fairly brief messages.

Many businesses use automated emails to acknowledge communications from the public, or to remind associates that periodic reports or payments are due. You may also be assigned to “populate” a form email in which standard paragraphs are used but you choose from a menu of sentences to make the wording suitable for a particular transaction.

Emails may be informal in personal contexts, but business communication requires attention to detail, awareness that your email reflects you and your company, and a professional tone so that it may be forwarded to any third party if needed. Email often serves to exchange information within organizations. Although email may have an informal feel, remember that when used for business, it needs to convey professionalism and respect. Never write or send anything that you wouldn’t want read in public or in front of your company president.

Tips for Effective Business Emails

- Proper salutations should demonstrate respect and avoid mix-ups in case a message is accidentally sent to the wrong recipient. For example, use a salutation like “Dear Ms. X” (external) or “Hi Barry” (internal).

- Subject lines should be clear, brief, and specific. This helps the recipient understand the essence of the message. For example, “Proposal attached” or “Your question of 10/25.”

- Close with a signature. Identify yourself by creating a signature block that automatically contains your name and business contact information.

- Avoid abbreviations. An email is not a text message, and the audience may not find your wit cause to ROTFLOL (roll on the floor laughing out loud).

- Be brief. Omit unnecessary words.

- Use accepted formatting. Include line breaks between sentences or divide your message into brief paragraphs for ease of reading. A good email should get to the point and conclude in three small paragraphs or less.

- Reread, revise, and review. Catch and correct spelling and grammar mistakes before you press “send.” It will take more time and effort to undo the problems caused by a hasty, poorly written email than to get it right the first time.

- Reply promptly. Watch out for an emotional response—never reply in anger—but make a habit of replying to all emails within twenty-four hours, even if only to say that you will provide the requested information in forty-eight or seventy-two hours.

- Use “Reply All” sparingly. Do not send your reply to everyone who received the initial email unless your message absolutely needs to be read by the entire group.

- Avoid using all caps. Capital letters are used on the Internet to communicate emotion or yelling and are considered rude.

- Test links. If you include a link, test it to make sure it is complete.

- Email ahead of time if you are going to attach large files (audio and visual files are often quite large) to prevent exceeding the recipient’s mailbox limit or triggering the spam filter.

- Give feedback or follow up. If you don’t receive a response in twenty-four hours, email or call. Spam filters may have intercepted your message, so your recipient may never have received it.

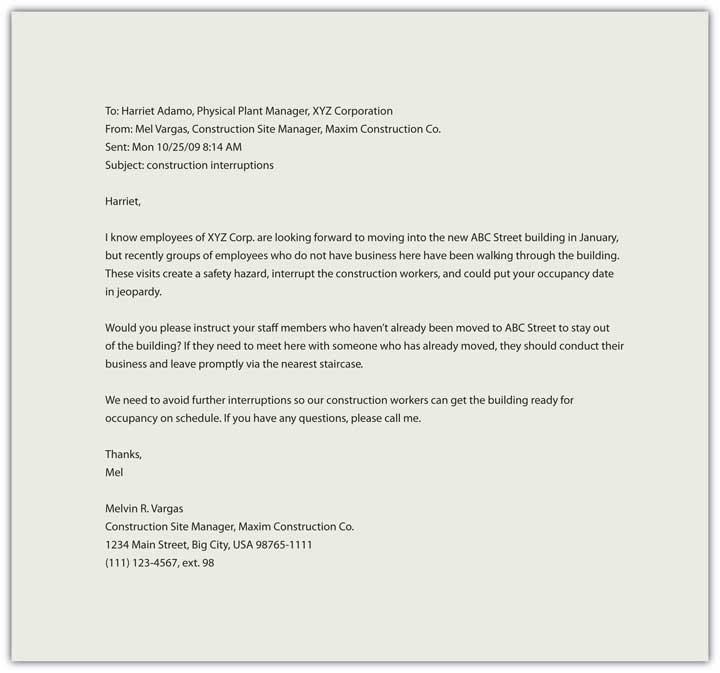

For reference, please review the example of a business email below. Figure 2 is a letter written specifically for the situation and audience.

Netiquette

We create personal pages, post messages, and interact via mediated technologies as a normal part of our careers, but how we conduct ourselves can leave a lasting image, literally. The photograph you posted on your Facebook, Instagram, or Snapchat may have been seen by your potential employer, or that nasty remark in a post may come back to haunt you later. Some fifteen years ago, when the Internet was a new phenomenon, Virginia Shea laid out a series of ground rules for communication online that continue to serve us today.

Virginia Shea’s Rules of Netiquette

- Remember the human on the other side of the electronic communication.

- Adhere to the same standards of behavior online that you follow in real life.

- Know where you are in cyberspace.

- Respect other people’s time and bandwidth.

- Make yourself look good online.

- Share expert knowledge.

- Keep flame wars under control.

- Respect other people’s privacy.

- Don’t abuse your power.

- Be forgiving of other people’s mistakes.

Shea, V. (1994). Netiquette. San Francisco, CA: Albion Books.

Her rules speak for themselves and remind us that the golden rule (treat others as you would like to be treated) is relevant wherever there is human interaction.

Although email is a valuable communication tool, its widespread use in academic and business settings has introduced some new challenges for writers.

Because it is a relatively new form of communication, basic social conventions for writing and responding to email are still being worked out. Miscommunication can easily occur when people have different expectations about the emails that they send and receive. In addition, email is used for many different purposes, including contacting friends, communicating with professors and supervisors, requesting information, and applying for jobs, internships, and scholarships. Depending on your purposes, the messages you send will differ in their formality, intended audience, and desired outcome. Finally, the use of email for advertising purposes has clogged communication channels, preventing some emails from reaching their intended audience. Writers are challenged to make their email stand apart from “spam” and to grab and hold the attention of their audience.

So—how do you know when sending an email is the most effective way of getting your message across? When is a brief message sufficient, and when it is more appropriate to send a longer, more professional email? How should a writer decide what style of writing is appropriate for each task? How can you prevent your email from ending up in the junk pile? Keep reading for answers to these questions!

When is Email the Appropriate Form of Communication to Use?

email is a good way to get your message across when:

- You need to communicate with a person who is hard to reach via telephone, does not come to campus regularly, or is not located in the same part of the country or world (for instance, someone who lives in a different time zone).

- The information you want to share is not time-sensitive. The act of sending an email is instantaneous, but that does not mean the writer can expect an instantaneous response. For many people, keeping up with their email correspondence is a part of their job, and they only do it during regular business hours. Unless your reader has promised otherwise, assume that it may take a few days for him/her to respond to your message.

- You need to send someone an electronic file, such as a document for a course, a spreadsheet full of data, or a rough draft of your paper.

- You need to distribute information to a large number of people quickly (for example, a memo that needs to be sent to the entire office staff).

- You need a written record of the communication. Saving important emails can be helpful if you need to refer back to what someone said in an earlier message, provide some kind of proof (for example, proof that you have paid for a service or product), or review the content of an important meeting, deadline, memo.

When is Email Not an Appropriate Form of Communication to Use?

Email is not an effective means of communication when:

- Your message is long and complicated or requires additional discussion that would best be accomplished face-to-face. For example, if you want feedback from your supervisor on your work or if you are asking your professor a question that requires more than a yes/no answer or simple explanation, you should schedule a meeting instead.

- Information is highly confidential. Email is NEVER private! Keep in mind that your message could be forwarded on to other people without your knowledge. A backup copy of your email is always stored on a server where it can be easily retrieved by interested parties, even when you have deleted the message and think it is gone forever.

- Your message is emotionally charged or the tone of the message could be easily misconstrued. If you would hesitate to say something to someone’s face, do not write it in an email.

Who is Your Audience?

People have different opinions about the form and content of emails, so it is always helpful to be aware of the expectations of your audiences. For example, some people regard email as a rapid and informal form of communication—a way to say “hello” or to ask a quick question. However, others view email as simply a more convenient way to transmit a formal letter. Such people may consider an informal email rude or unprofessional.

A message like this one might be o.k. to send your friend, but not to your professor:

Hey Joan,

Do you know what the assignment is about? Can U help me?

M

Although it may be obvious to you that you wouldn’t send such an email to your professor, let’s carefully examine what assumptions this message makes about the reader and his/her expectations.

The tone of this message is casual; it assumes that the reader knows who the sender is and has a close personal relationship with the sender. Because it contains an ambiguous reference to “the assignment,” this message also assumes that the reader is familiar with the subject matter at hand (for instance, it assumes the reader will know which course and which particular assignment the sender is referring to). In this message, the writer also makes an implicit assumption about the reader’s familiarity with the slang that is often used when sending an instant message or text message. If the reader is not familiar with this type of slang, the “U” in “Can U help me?” might be confusing, or it might even be taken as a sign that the writer is too lazy to type out the word “you.”

Making assumptions about your audience’s expectations increases the risk that your message or its tone will be misinterpreted. To ensure that your message has its intended effect, use the following questions to help you think about your audience and their needs:

- Who is your audience? How often does your audience use email to communicate? How comfortable is your audience with using electronic communication—for example, when in their lifetime did they begin using email (childhood or adulthood)?

- What is your audience’s relationship to you—for example, is the reader your teacher? Your boss? A friend? A stranger? How well do you know him/her? How would you talk to him/her in a social situation?

- What do you want your audience to think or assume about you? What kind of impression do you want to make?

Important components of an effective email:

Subject Lines

Email subject lines are like newspaper headlines. They should convey the main point of your email or the idea that you want the reader to take away from your email. Therefore, be as specific as possible. One word subjects such as “Hi,” “Question,” or “FYI” are not informative and don’t give the reader an idea of how important your message is. If your message is time sensitive, you might want to include a date in your subject line, for example, “Meeting on Thurs, Dec 2.”

Greetings and Sign-offs

Include a greeting, also known as a salutation, and a closing statement. Don’t just start with your text, and don’t stop at the end without a polite signature. If you don’t know the person well, you may be confused about how to address him/her (“What do I call my TA/professor?”) or how to sign off (From? Sincerely?). Nonetheless, it is always better to make some kind of effort. When in doubt, address someone more formally to avoid offending them. Some common ways to address your reader are:

- Dear Professor Varela,

- Hello Ms. McMahon,

- Hi Mary Jane,

It is always better to address a specific person, but if you are unable to locate the name of the person you are addressing, or if the email addresses a diverse group, try something generic, yet polite:

- Dear members of the selection committee,

- Hello everyone,

Your closing is extremely important because it lets the reader know who is contacting them. Always sign off with your name at the end of your email. If you don’t know the reader well, you might also consider including your title and the organization you belong to; for example:

- Mary Watkins

Senior Research Associate

Bain and Company

- Joseph Smith

English 1210-53 Student

For your closing, something brief but friendly, or perhaps just your name, will do for most correspondence:

- Thank you,

- Best wishes,

- See you tomorrow,

- Regards,

For a formal message, such as a job application, use the kind of closing that you might see in a business letter:

- Sincerely,

-

Respectfully yours,

Cc: and Bcc: (‘Carbon copy’ and ‘Blind carbon copy’)

Copying individuals on an email is a good way to send your message to the main recipient while also sending someone else a copy at the same time. This can be useful if you want to convey the same exact message to more than one person. In professional settings, copying someone else on an email can help move a project forward, especially if the person receiving the copy is in a supervisory role. For example, copying your boss on an email to a non-responsive co-worker might prompt the co-worker to respond. Be aware, however, that when you send a message to more than one address using the Cc: field, both the original recipient and all the recipients of the carbon copies can see all the email addresses in the To: and Cc: fields. Each person who receives the message will be able to see the addresses of everyone else who received it.

Blind copying emails to a group of people can be useful when you don’t want everyone on the list to have each other’s email addresses. The only recipient address that will be visible to all recipients is the one in the To: field. If you don’t want any of the recipients to see the email addresses in the list, you can put your own address in the To: field and use Bcc: exclusively to address your message to others. However, do not assume that blind copying will always keep recipients from knowing who else was copied—someone who is blind copied may hit “reply all” and send a reply to everyone, revealing that he/she was included in the original message.

Some Additional Tips for Writing More Effective Emails:

Think about your message before you write it. Don’t send emails in haste. First, decide on the purpose of your email and the outcome you expect from your communication. Then think about your message’s audience and what he/she/they may need in order for your message to have the intended result. You will also improve the clarity of your message if you organize your thoughts before you start writing. Jot down some notes about what information you need to convey, what questions you have, etc., then organize your thoughts in a logical sequence. You can try brainstorming techniques like mapping, listing, or outlining to help you organize your thoughts.

Reflect on the tone of your message. When you are communicating via email, your words are not supported by gestures, voice inflections, or other cues, so it may be easier for someone to misread your tone. For example, sarcasm and jokes are often misinterpreted in emails and may offend your audience. Similarly, be careful about how you address your reader. For instance, beginning an email to your professor or TA with “Hey!” might be perceived as being rude or presumptuous (as in, “Hey you!”). If you’re unsure about how your email might be received, you might try reading it out loud to a friend to test its tone.

Strive for clarity and brevity in your writing. Have you ever sent an email that caused confusion and took at least one more communication to straighten out? Miscommunication can occur if an email is unclear, disorganized, or just too long and complex for readers to easily follow. Here are some steps you can take to ensure that your message is understood:

- Briefly state your purpose for writing the email in the beginning of your message.

- Be sure to provide the reader with a context for your message. If you’re asking a question, cut and paste any relevant text (for example, computer error messages, assignment prompts you don’t understand, part of a previous email message, etc.) into the email so that the reader has some frame of reference for your question. When replying to someone else’s email, it can often be helpful to either include or restate the sender’s message.

- Use paragraphs to separate thoughts (or consider writing separate emails if you have many unrelated points or questions).

- Finally, state the desired outcome at the end of your message. If you’re requesting a response, let the reader know what type of response you require (for example, an email reply, possible times for a meeting, a recommendation letter, etc.) If you’re requesting something that has a due date, be sure to highlight that due date in a prominent position in your email. Ending your email with the next step can be really useful, especially in work settings (for example, you might write “I will follow this email up with a phone call to you in the next day or so” or “Let’s plan to further discuss this at the meeting on Wednesday”).

Format your message so that it is easy to read. Use white space to visually separate paragraphs into separate blocks of text. Bullet important details so that they are easy to pick out. Use bold face type or capital letters to highlight critical information, such as due dates. (But do not type your entire message in capital letters or boldface—your reader may perceive this as “shouting” and won’t be able to tell which parts of the message are especially important.)

Proofread

Re-read messages before you send them. Use proper grammar, spelling, capitalization, and punctuation. If your email program supports it, use spelling and grammar checkers. Try reading your message out loud to help you catch any grammar mistakes or awkward phrasing that you might otherwise miss.

Questions to Ask Yourself Before Sending an Email Message:

- Is this message suitable for email, or could I better communicate the information with a letter, phone call, or face-to-face meeting?

- What is my purpose for sending this email? Will the message seem important to the receiver, or will it be seen as an annoyance and a waste of time?

- How many emails does the reader usually receive, and what will make him/her read this message (or delete it)?

- Do the formality and style of my writing fit the expectations of my audience?

- How will my message look when it reaches the receiver? Is it easy to read? Have I used correct grammar and punctuation? Have I divided my thoughts into discrete paragraphs? Are important items, such as due dates, highlighted in the text?

- Have I provided enough context for my audience to easily understand or follow the thread of the message?

- Did I identify myself and make it easy for the reader to respond in an appropriate manner?

- Will the receiver be able to open and read any attachments?

Letters

Principles to Keep in Mind: Business Writing is Different

Writing for a business audience is usually quite different than writing in the humanities, social sciences, or other academic disciplines. Business writing strives to be crisp and succinct rather than evocative or creative; it stresses specificity and accuracy. This distinction does not make business writing superior or inferior to other styles. Rather, it reflects the unique purpose and considerations involved when writing in a business context.

When you write a business document, you must assume that your audience has limited time to read it and is likely to skim. Your readers have an interest in what you say insofar as it affects their working world. They want to know the “bottom line”: the point you are making about a situation or problem and how they should respond.

Business writing varies from the conversational style often found in email messages to the more formal, legalistic style found in contracts. A style between these two extremes is appropriate for the majority of memos, emails, and letters. Writing that is too formal can alienate readers, and an attempt to be overly casual may come across as insincere or unprofessional. In business writing, as in all writing, you must know your audience.

There are some similarities within the genres of letter writing and memo writing. The following video goes over this and more:

In most cases, the business letter will be the first impression that you make on someone. Though business writing has become less formal over time, you should still take great care that your letter’s content is clear and that you have proofread it carefully.

Pronouns and Active versus Passive Voice

Personal pronouns (I, we, and you) are important in letters and memos. In such documents, it is perfectly appropriate to refer to yourself as “I” and to the reader as “you”. Be careful, however, when you use the pronoun “we” in a business letter that is written on company stationery, since it commits your company to what you have written. When stating your opinion, use “I”; when presenting company policy, use “we”.

The best writers strive to achieve a style that is so clear that their messages cannot be misunderstood. One way to achieve a clear style is to minimize your use of the passive voice, which is a sentence where the subject receives an action. Although the passive voice is sometimes necessary, often it not only makes your writing dull but also can be ambiguous or overly impersonal. Here’s an example of the same point stated in passive voice and in the active voice:

PASSIVE: The net benefits of subsidiary divestiture were grossly overestimated. [Who did the overestimating?]

ACTIVE: The Global Finance Team grossly overestimated the net benefits of subsidiary divestiture.

The second version is clearer and thus preferable.

Of course, there are exceptions to every rule. What if you are the head of the Global Finance Team? You may want to get your message across without calling excessive attention to the fact that the error was your team’s fault. The passive voice allows you to gloss over an unflattering point—but you should use it sparingly.

Focus and Specificity

Business writing should be clear and concise. Take care, however, that your document does not turn out as an endless series of short, choppy sentences. Keep in mind also that “concise” does not have to mean “blunt”—you still need to think about your tone and the audience for whom you are writing. Consider the following examples:

- After carefully reviewing this proposal, we have decided to prioritize other projects this quarter.

- Nobody liked your project idea, so we are not going to give you any funding.

The first version is a weaker statement, emphasizing facts not directly relevant to its point. The second version provides the information in a simple and direct manner. But you don’t need to be an expert on style to know that the first phrasing is diplomatic and respectful (even though it’s less concise) as compared with the second version, which is unnecessarily harsh and likely to provoke a negative reaction.

Business Letters: Where to Begin

Before you begin to draft a business letter, spend a moment to reread the description of your task (for example, the advertisement of a job opening, instructions for a proposal submission, or assignment prompt for a course).

- Think about your purpose and what requirements are mentioned or implied in the description of the task. List these requirements. This list can serve as an outline to govern your writing and help you stay focused, so try to make it thorough.

- Identify qualifications, attributes, objectives, or answers that match the requirements you have just listed. Strive to be exact and specific, avoiding vagueness, ambiguity, and platitudes. If there are industry- or field-specific concepts or terminology that are relevant to the task at hand, use them in a manner that will convey your competence and experience.

- Avoid any language that your audience may not understand. Your finished piece of writing should indicate how you meet the requirements you’ve listed and answer any questions raised in the description or prompt.

Common Components of a Business Letter

The following visual is concerned with the mechanical and physical details of business letters. All of the essential components of a traditional business letter are illustrated below:

Common Components of Business Letters

Heading. The heading contains the writer’s address and the date of the letter. The writer’s name is not included; only a date is needed in headings on letterhead stationery

Inside address. The inside address shows the name and address of the recipient of the letter. This information can help prevent confusion at the recipient’s offices. Also, if the recipient has moved, the inside address helps to determine what to do with the letter. In the inside address, include the appropriate title of respect of the recipient; and copy the name of the company exactly as that company writes it. When you are unable to locate the names of individuals, remember to address them appropriately: Mrs., Ms., Mr., Dr., and so on. If you are not sure what is correct for an individual, try to find out how that individual signs letters or consult the forms-of-address section in a dictionary.

Salutation. The salutation directly addresses the recipient of the letter and is followed by a colon (except when a friendly, familiar, sociable tone is intended, in which case a comma is used). Notice that in the simplified letter format, the salutation line is eliminated altogether. If you don’t know whether the recipient is a man or woman, the traditional practice has been to write “Dear Sir” or “Dear Sirs”—but that’s sexist! To avoid this problem, salutations such as “Dear Sir or Madame,” “Dear Ladies and Gentlemen,” “Dear Friends,” or “Dear People” have been tried—but without much general acceptance. Deleting the salutation line altogether or inserting “To Whom It May Concern” in its place, is not ordinarily a good solution either—it’s impersonal.

Always spend the extra time to locate the name of the person you are writing to; the best solution is to make a quick, anonymous phone call to the organization and ask for a name. If that strategy is unsuccessful, the last resort is to address the salutation to a department name, committee name, or a position name: “Dear Personnel Department,” “Dear Recruitment Committee,” “Dear Chairperson,” “Dear Director of Financial Aid,” for example.

Subject or reference line. As shown in the order letter, the subject line replaces the salutation or is included with it. The subject line announces the main business of the letter.

Body of the letter. The actual message of course is contained in the body of the letter, the paragraphs between the salutation and the complimentary close.

Complimentary close. The “Sincerely yours” element of the business letter is called the complimentary close. Other common ones are “Sincerely yours,” “Cordially,” “Respectfully,” or “Respectfully yours.” You can design your own, but be careful not to create florid or wordy ones. Notice that only the first letter is capitalized, and it is always followed by a comma.

Signature block. Usually, you type your name four lines below the complimentary close, and sign your name in between. If you are a woman and want to make your marital status clear, use Miss, Ms., or Mrs. in parentheses before the typed version of your first name. Whenever possible, include your title or the name of the position you hold just below your name. For example, “Technical writing student,” “Sophomore data processing major,” or “Tarrant County Community College Student” are perfectly acceptable.

End notations. Just below the signature block are often several abbreviations or phrases that have important functions.

- Initials. The initials in all capital letters in the preceding figures are those of the writer of the letter, and the ones in lower case letters just after the colon are those of the typist.

- Enclosures. To make sure that the recipient knows that items accompany the letter in the same envelope, use such indications as “Enclosure,” “Encl.,” “Enclosures (2).” For example, if you send a resume and writing sample with your application letter, you’d do this: “Encl.: Resume and Writing Sample.” If the enclosure is lost, the recipient will know.

- Copies. If you send copies of a letter to others, indicate this fact among the end notations also. If, for example, you were upset by a local merchant’s handling of your repair problems and were sending a copy of your letter to the Better Business Bureau, you’d write this: “cc: Better Business Bureau.” If you plan to send a copy to your lawyer, write something like this: “cc: Mr. Raymond Mason, Attorney.

The memo section of chapter four “Basic Workplace Genres” is synthesized from the following sources:

- “Chapter 4 Technical Documents” of ENGL 145: Technical and Report Writing, 2017, written by Amber Kinonen and used according to Creative Commons CC BY 4.0

- And “Module Seven: Memos–Purpose and Format” from Lumen Learning’s Technical Writing course, found at the following address: https://www.oercommons.org/courses/technical-writing/view and used according to Creative Commons CC BY 4.0

- Lewis, L. (2009, February 13). Panasonic orders staff to buy £1,000 in products. Retrieved from http://business.timesonline.co.uk/tol/business/markets/japan/article5723942.ece

The letter and email sections of chapter four “Basic Workplace Genres” are adapted from “Chapter 4 Technical Documents” of ENGL 145: Technical and Report Writing, 2017, written by Amber Kinonen and used according to Creative Commons CC BY 4.0