In order to understand how we use verbal communication to create shared meaning in interactions, we first must become familiar with its characteristics. In this section, we will discuss how verbal messages are made of up of a system of symbols, are learned, are rule-governed, and have both denotative and connotative meanings.

5.2.1: Verbal Messages are a System of Symbols

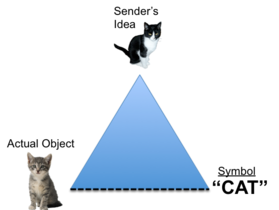

Our language system is primarily made up of symbols. A symbol is something that stands in for or represents something else. Symbols can be communicated verbally (speaking the word hello), in writing (putting the letters H-E-L-L-O together), or nonverbally (waving your hand back and forth). In any case, the symbols we use stand in for something else, like a physical object or an idea; they do not actually correspond to the thing being referenced in any direct way. For example, there is nothing inherent about calling a cat a cat. Rather, English speakers have agreed that these symbols (words), whose components (letters) are used in a particular order each time, stand for both the actual object, as well as our interpretation of that object. This idea is illustrated by C. K. Ogden and I. A. Richard’s triangle of meaning. The word “cat” is not the actual cat. Nor does it have any direct connection to an actual cat. Instead, it is a symbolic representation of our idea of a cat, as indicated by the line going from the word “cat” to the speaker’s idea of “cat” to the actual object.

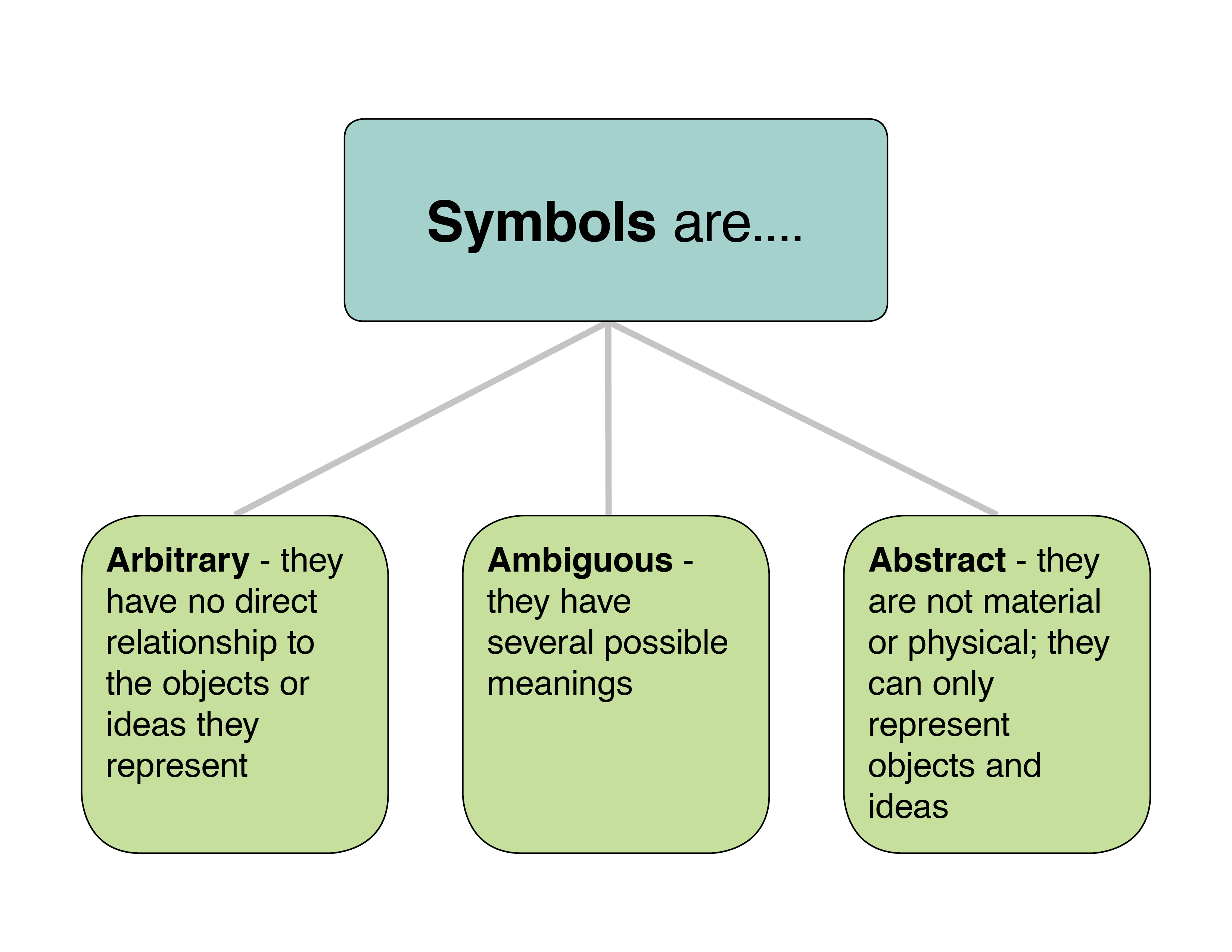

The verbal symbols that we use to communicate have three distinct qualities: they are arbitrary, ambiguous, and abstract. Notice that the picture of the cat on the left side of the triangle more closely represents a real cat than the word “cat.” However, we do not use pictures as language, or verbal communication. Instead, we use words to represent our ideas. This example demonstrates our agreement that the word “cat” represents or stands for a real cat AND our idea of a cat. The symbols we use are arbitrary and have no direct relationship to the objects or ideas they represent. We generally consider communication successful when we reach agreement on the meanings of the symbols we use.

Not only are symbols arbitrary, they are ambiguous- that is, they have several possible meanings. For example, when the word “cat” is uttered alone and without context, most people might envision a small, house cat. However, “cat” has other possible meanings. Lion? Nickname for Catherine? Cool person? Heavy construction machinery? Imagine your friend tells you they have an apple on their desk. Are they referring to a piece of fruit or their computer? If a friend says that a person they met is cool, do they mean that person is cold or awesome? The meanings of symbols change over time due to changes in social norms, values, and advances in technology. We are able to communicate because there are a finite number of possible meanings for our symbols, a range of meanings which the members of a given language system agree upon. Without an agreed-upon system of symbols, we could share relatively little meaning with one another.

The verbal symbols we use are also abstract, meaning that, words are not material or physical. A certain level of abstraction is inherent in the fact that symbols can only represent objects and ideas. This abstraction allows us to use a phrase like “the public” in a broad way to mean all the people in the United States rather than having to distinguish among all the diverse groups that make up the U.S. population. Similarly, in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter book series, wizards and witches call the non-magical population on earth “muggles” rather than having to define all the separate cultures of muggles. Abstraction is helpful when you want to communicate complex concepts in a simple way. However, the more abstract the language, the greater potential there is for confusion. Saying “cat” is not as abstract as saying “animal,” but also will not necessarily bring an image of a much more specific white cat named “Calliope” to the mind of your listener, if that is your intention.

5.2.2: Verbal Messages are Learned

As we just learned, the relationship between the symbols that make up our language and their referents is arbitrary, which means they have no meaning until we assign it to them. In order to effectively use a language system, we have to learn, over time, which symbols go with which referents, since we can’t just tell by looking at the symbol. Like me, you probably learned what the word apple meant by looking at the letters A-P-P-L-E and a picture of an apple and having a teacher or caregiver help you sound out the letters until you said the whole word. Over time, we associated that combination of letters with an apple. Similarly, in a Spanish-speaking community, students assigned meaning to a different symbol for this fruity referent. The symbol is M-A-N-Z-A-N-A. Same referent, different symbol.

5.2.3: Verbal Messages are Rule-Governed

When using written channels to communicate verbally, spelling and punctuation can be an important part of creating shared understanding.

Verbal communication is rule-governed. We must follow agreed-upon rules to make sense of the symbols we share. Let’s take another look at our example of the word cat. What would happen if there were no rules for using the symbols (letters) that make up this word? If placing these symbols in a proper order was not important, then cta, tac, tca, act, or atc could all mean cat. Any language system has to have rules to make it learnable and usable. Grammar refers to the rules that govern how words are used to make phrases and sentences. Someone would likely know what you mean by the question “Where’s the remote control?” But “The control remote where’s?” is likely to be unintelligible or at least confusing (Crystal, 2005). Knowing the rules of grammar is important in order to be able to write and speak to be understood. However, those rules are also open and flexible, allowing a person to make choices to determine meaning (Eco, 1976).

In addition, the rules that guide our verbal messages can differ through different communication channels, such as academic papers, face-to-face interactions, text messages, or social media. When writing an academic paper, grammatical rules are important to follow, and spelling and punctuation play an important role in conveying meaning. For example, “Let’s eat Grandma” is different in meaning from “Let’s eat, Grandma.” However, when communicating through a text message, the rules are usually more relaxed, flexible, and dynamic; communicators will often use abbreviations, acronyms, and slang to convey meaning, and may forgo punctuation or use it strategically to modify word meaning.

5.2.4: Verbal Messages Have Both Denotative and Connotative Meanings

We attach meanings to words; meanings are not inherent in words themselves. As you’ve been reading, words (symbols) are arbitrary and attain meaning only when people give them meaning. While we can always look to a dictionary to find a standardized definition of a word, or its denotative meaning, meanings do not always follow standard, agreed-upon definitions when used in various contexts. For example, think of the word “sick”. The denotative definition of the word is ill or unwell. However, connotative meanings, the meanings we assign based on our experiences and beliefs, are quite varied. For example, take the word ‘hippie’, the denotative meaning or dictionary definition is “a usually young person who rejects the mores of established society (as by dressing unconventionally or favoring communal living) and advocates a nonviolent ethic” (Webster, 2019). However, what comes to mind when you think of the word hippie? Long hair? Tye-dye shirts? Drugs? This is the connotative meaning, the things you associate with that particular world. Connotative meanings can be positive, negative, and/or neutral and what WE associate with word may change over time and vary based on individual experiences. For example, a person who liked road trips as child may have a positive association with that phrase, while a person who disliked them may have a negative association.