The importance of establishing and maintaining relationships in middle adulthood is now well established in academic literature—there are now thousands of published articles purporting to demonstrate that social relationships are integral to any aspects of subjective well-being and physiological functioning, and these help to inform actual healthcare practices. Studies show an increased risk of dementia, cognitive decline, susceptibility to vascular disease, and increased mortality in those who feel isolated and alone. However, loneliness is not confined to people living a solitary existence. It can also refer to those who endure a perceived discrepancy in the socio-emotional benefits of interactions with others, either in number or nature. One may have an expansive social network and still feel a dearth of emotional satisfaction in one’s own life.

Socioemotional selectivity theory (SST) predicts a quantitative decrease in the number of social interactions in favor of those bringing greater emotional fulfillment. Over the past thirty years, or more, there have been significant social changes that have, in turn, had a large effect on human bonding. These have affected the way we manage our emotional interactions, and how society views, shapes and supports that emotional regulation. Government policy has also changed and had a profound influence on how families are shaped, reshaped, and operate as social and economic agents.

Relationships and Family Life in Middle Adulthood

Types of Relationships

Intimate Relationships

It makes sense to consider the various types of relationships in our lives when trying to determine just how relationships impact our well-being. For example, would you expect a person to derive the same happiness from an ex-spouse as from a child or coworker? Among the most important relationships for most people is their long-time romantic partner. Most researchers begin their investigation of this topic by focusing on intimate relationships because they are the closest form of social bond. Intimacy is more than just physical in nature; it also entails psychological closeness. Research findings suggest that having a single confidante—a person with whom you can be authentic and trust not to exploit your secrets and vulnerabilities—is more important to happiness than having a large social network (Taylor, 2010).

Another important aspect of relationships is the distinction between formal and informal. Formal relationships are those that are bound by the rules of politeness. In most cultures, for instance, young people treat older people with formal respect, avoiding profanity and slang when interacting with them. Similarly, workplace relationships tend to be more formal, as do relationships with new acquaintances. Formal connections are generally less relaxed because they require a bit more work, demanding that we exert more self-control. Contrast these connections with informal relationships—friends, lovers, siblings, or others with whom you can relax. We can express our true feelings and opinions in these informal relationships, using the language that comes most naturally to us, and generally, be more authentic. Because of this, it makes sense that more intimate relationships—those that are more comfortable and in which you can be more vulnerable—might be the most likely to translate to happiness.

Marriage and Happiness

One of the most common ways that researchers often begin to investigate intimacy is by looking at marital status. The well-being of married people is compared to that of people who are single or have never been married. In other research, married people are compared to people who are divorced or widowed (Lucas & Dyrenforth, 2005). Researchers have found that the transition from singlehood to marriage brings about an increase in subjective well-being (Haring-Hidore, Stock, Okun, & Witter, 1985; Lucas, 2005; Williams, 2003). In fact, this finding is one of the strongest in social science research on personal relationships over the past quarter of a century.

As is usually the case, the situation is more complex than might initially appear. As a marriage progresses, there is some evidence for regression to a hedonic set-point—that is, most individuals have a set happiness point or level, and that both good and bad life events – marriage, bereavement, unemployment, births, and so on – have some effect for a period of time, but over many months, they will return to that set-point. One of the best studies in this area is that of Luhmann et al (2012), who report a gradual decline in subjective well-being after a few years, especially in the component of affective well-being. Adverse events obviously affect subjective well-being and happiness, and these effects can be stronger than the positive effects of being married in some cases (Lucas, 2005).

Although research frequently points to marriage being associated with higher rates of happiness, this does not guarantee that getting married will make you happy! The quality of one’s marriage matters greatly. When a person remains in a problematic marriage, it takes an emotional toll. Indeed, a large body of research shows that people’s overall life satisfaction is affected by their satisfaction with their marriage (Carr, Freedman, Cornman, Schwarz, 2014; Dush, Taylor, & Kroeger, 2008; Karney, 2001; Luhmann, Hofmann, Eid, & Lucas, 2012; Proulx, Helms, & Buehler, 2007). The lower a person’s self-reported level of marital quality, the more likely he or she is to report depression (Bookwala, 2012). In fact, longitudinal studies—those that follow the same people over a period of time—show that as marital quality declines, depressive symptoms increase (Fincham, Beach, Harold, & Osborne, 1997; Karney, 2001). Proulx and colleagues (2007) arrived at this same conclusion after a systematic review of 66 cross-sectional and 27 longitudinal studies.

Marital satisfaction has peaks and valleys during the course of the life cycle. Rates of happiness are highest in the years before the birth of the first child. It hits a low point with the coming of children. Relationships typically become more traditional and there are more financial hardships and stress in living. Children bring new expectations to the marital relationship. Two people who are comfortable with their roles as partners may find the added parental duties and expectations more challenging to meet. Some couples elect not to have children to have more time and resources for the marriage. These child-free couples are happy keeping their time and attention on their partners, careers, and interests.

What is it about bad marriages or bad relationships in general, that take such a toll on well-being? Research has pointed to conflict between partners as a major factor leading to lower subjective well-being (Gere & Schimmack, 2011). This makes sense. Negative relationships are linked to ineffective social support (Reblin, Uchino, & Smith, 2010) and are a source of stress (Holt-Lunstad, Uchino, Smith, & Hicks, 2007). In more extreme cases, physical and psychological abuse can be detrimental to well-being (Follingstad, Rutledge, Berg, Hause, & Polek, 1990). Victims of abuse sometimes feel shame, lose their sense of self, and become less happy and prone to depression and anxiety (Arias & Pape, 1999). However, the unhappiness and dissatisfaction that occur in abusive relationships tend to dissipate once the relationships end. (Arriaga, Capezza, Goodfriend, Rayl & Sands, 2013).

Marital Communication

Advice on how to improve one’s marriage is centuries old. One of today’s experts on marital communication is John Gottman. Gottman differs from many marriage counselors in his belief that having a good marriage does not depend on compatibility, rather, the way that partners communicate with one another is crucial. At the University of Washington in Seattle, Gottman has measured the physiological responses of thousands of couples as they discuss issues that have led to disagreements. Fidgeting in one’s chair, leaning closer to or further away from the partner while speaking, and increases in respiration and heart rate are all recorded and analyzed, along with videotaped recordings of the partners’ exchanges.

Gottman believes he can accurately predict whether or not a couple will stay together by analyzing their communication. In marriages destined to fail, partners engage in the “marriage killers” such as contempt, criticism, defensiveness, and stonewalling. Each of these undermines the politeness and respect that healthy marriages require. According to Gottman, stonewalling, or shutting someone out, is the strongest sign that a relationship is destined to fail. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of Gottman’s work is the emphasis on the fact that marriage is about constant negotiation rather than conflict resolution.

What Gottman terms perpetual problems, are responsible for 69% of conflicts within marriage. For example, if someone in a couple has said, “I am so sick of arguing over this,” then that may be a sign of a perpetual problem. While this may seem problematic, Gottman argues that couples can still be connected despite these perpetual problems if they can laugh about it, treat it as a “third thing” (not reducible to the perspective of either party), and recognize that these are part of relationships that need to be aired and dealt with as best you can. It is somewhat refreshing to hear that differences lie at the heart of marriage, rather than a rationale for its dissolution!

Parenting in Later Life

Just because children grow up does not mean their family stops being a family, rather the specific roles and expectations of its members change over time. One major change comes when a child reaches adulthood and moves away. When exactly children leave home varies greatly depending on societal norms and expectations, as well as on economic conditions such as employment opportunities and affordable housing options. Some parents may experience sadness when their adult children leave the home—a situation called an empty nest.

Many parents are also finding that their grown children are struggling to launch into independence. It’s an increasingly common story: a child goes off to college and, upon graduation, is unable to find steady employment. In such instances, a frequent outcome is for the child to return home, becoming a “boomerang kid.” The boomerang generation, as the phenomenon has come to be known, refers to young adults, mostly between the ages of 25 and 34, who return home to live with their parents while they strive for stability in their lives—often in terms of finances, living arrangements, and sometimes romantic relationships. These boomerang kids can be both good and bad for families. Within American families, 48% of boomerang kids report having paid rent to their parents, and 89% say they help out with household expenses—a win for everyone (Parker, 2012). On the other hand, 24% of boomerang kids report that returning home hurts their relationship with their parents (Parker, 2012). For better or for worse, the number of children returning home has been increasing around the world. The Pew Research Center (2016) reported that the most common living arrangement for people aged 18-34 was living with their parents (32.1%).

Adult children typically maintain frequent contact with their parents, if for no other reason, money, and advice. Attitudes toward one’s parents may become more accepting and forgiving, as parents are seen in a more objective way, as people with good points and bad. As adults children can continue to be subjected to criticism, ridicule, and abuse at the hand of parents. How long are we “adult children”? For as long as our parents are living, we continue in the role of son or daughter. (I had a neighbor in her nineties who would tell me her “boys” were coming to see her this weekend. Her boys were in there 70s-but they were still her boys!) But after one’s parents are gone, the adult is no longer a child; as one 40-year-old man explained after the death of his father, “I’ll never be a kid again.”

Family Issues and Considerations

In addition to middle-aged parents spending more time, money, and energy taking care of their adult children, they are also increasingly taking care of their own aging and ailing parents. Middle-aged people in this set of circumstances are commonly referred to as the sandwich generation (Dukhovnov & Zagheni, 2015). Of course, cultural norms and practices again come into play. In some Asian and Hispanic cultures, the expectation is that adult children are supposed to take care of aging parents and parents-in-law. In other Western cultures—cultures that emphasize individuality and self-sustainability—the expectation has historically been that elders either age in place, modifying their home, and receiving services to allow them to continue to live independently or enter long-term care facilities. However, given financial constraints, many families find themselves taking in and caring for their aging parents, increasing the number of multigenerational homes around the world.

Being a midlife child often involves kinkeeping; organizing events and communication to maintain family ties. This role was first defined by Carolyn Rosenthal (1985). Kinkeepers are often midlife daughters (they are the person who tells you what food to bring to a gathering, or arranges a family reunion). They can often function as “managers” who maintain family ties and lines of communication. This is true for both large nuclear families, reconstituted, and multi-generational families. Rosenthal found that over half of the families she sampled were capable of identifying the individual who performed this role. Often adults at this stage of their lives are pressed into caregiving roles. Often referred to as the “sandwich generation”, they are still looking out for their own children while simultaneously caring for elderly parents. Given shifts in longevity and increasing costs for professional care of the elderly, this role will likely expand, placing ever greater pressure on careers.

Abuse in Family Life

Abuse can occur in multiple forms and across all family relationships. Breiding, Basile, Smith, Black, & Mahendra (2015) define the forms of abuse as:

- Physical abuse: the use of intentional physical force to cause harm. Scratching, pushing, shoving, throwing, grabbing, biting, choking, shaking, slapping, punching, and hitting are common forms of physical abuse

- Sexual abuse: the act of forcing someone to participate in a sex act against his or her will. Such abuse is often referred to as sexual assault or rape. A marital relationship does not grant anyone the right to demand sex or sexual activity from anyone, even a spouse

- Psychological abuse: aggressive behavior that is intended to control someone else. Such abuse can include threats of physical or sexual abuse, manipulation, bullying, and stalking.

Abuse between partners is referred to as intimate partner violence; however, such abuse can also occur between a parent and child (child abuse), adult children and their aging parents (elder abuse), and even between siblings.

The most common form of abuse between parents and children is that of neglect. Neglect refers to a family’s failure to provide for a child’s basic physical, emotional, medical, or educational needs (DePanfilis, 2006). Harry Potter’s aunt and uncle, as well as Cinderella’s stepmother, could all be prosecuted for neglect in the real world.

Abuse is a complex issue, especially within families. There are many reasons people become abusers: poverty, stress, and substance abuse are common characteristics shared by abusers, although abuse can happen in any family. There are also many reasons adults stay in abusive relationships: (a) learned helplessness (the abused person believing he or she has no control over the situation); (b) the belief that the abuser can/will change; (c) shame, guilt, self-blame, and/or fear; and (d) economic dependence. All of these factors can play a role.

Children who experience abuse may “act out” or otherwise respond in a variety of unhealthy ways. These include acts of self-destruction, withdrawal, and aggression, as well as struggles with depression, anxiety, and academic performance. Researchers have found that abused children’s brains may produce higher levels of stress hormones. These hormones can lead to decreased brain development, lower stress thresholds, suppressed immune responses, and lifelong difficulties with learning and memory (Middlebrooks & Audage, 2008).

Happy Healthy Families

Our families play a crucial role in our overall development and happiness. They can support and validate us, but they can also criticize and burden us. For better or worse, we all have a family. In closing, here are strategies you can use to increase the happiness of your family:

- Teach morality—fostering a sense of moral development in children can promote well-being (Damon, 2004).

- Savor the good—celebrate each other’s successes (Gable, Gonzaga & Strachman, 2006).

- Use the extended family network—family members of all ages, including older siblings and grandparents, who can act as caregivers can promote family well-being (Armstrong, Birnie-Lefcovitch & Ungar, 2005).

- Create family identity—share inside jokes, fond memories, and frame the story of the family (McAdams, 1993).

- Forgive—Don’t hold grudges against one another (McCullough, Worthington & Rachal, 1997).

Divorce and Remarriage

Divorce

Divorce refers to the legal dissolution of a marriage. Depending on societal factors, divorce may be more or less of an option for married couples. Despite popular belief, divorce rates in the United States actually declined for many years during the 1980s and 1990s, and only just recently started to climb back up—landing at just below 50% of marriages ending in divorce today (Marriage & Divorce, 2016); however, it should be noted that divorce rates increase for each subsequent marriage, and there is considerable debate about the exact divorce rate. Are there specific factors that can predict divorce? Are certain types of people or certain types of relationships more or less at risk for breaking up? Indeed, several factors appear to be either risk factors or protective factors.

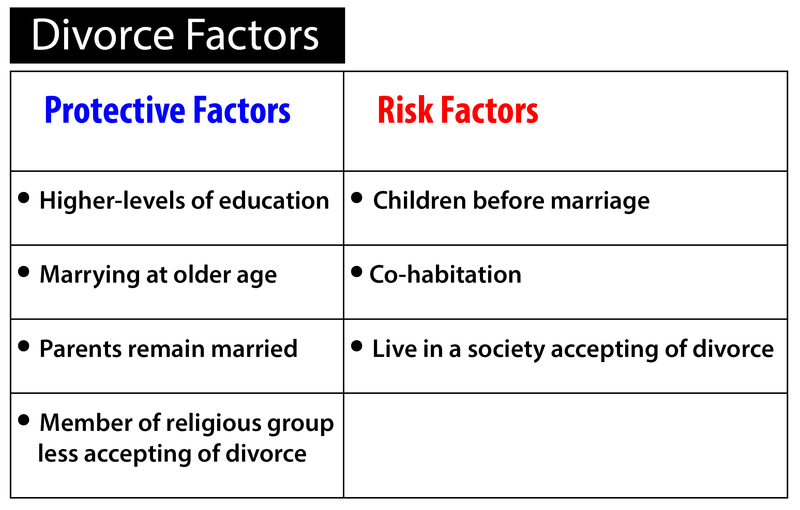

Pursuing education decreases the risk of divorce. So too does waiting until we are older to marry. Likewise, if our parents are still married we are less likely to divorce. Factors that increase our risk of divorce include having a child before marriage and living with multiple partners before marriage, known as serial cohabitation (cohabitation with one’s expected marital partner does not appear to have the same effect). Of course, societal and religious attitudes must also be taken into account. In societies that are more accepting of divorce, divorce rates tend to be higher. Likewise, in religions that are less accepting of divorce, divorce rates tend to be lower. See Lyngstad & Jalovaara (2010) for a more thorough discussion of divorce risk.

If a couple does divorce, there are specific considerations they should take into account to help their children cope. Parents should reassure their children that both parents will continue to love them and that the divorce is in no way the children’s fault. Parents should also encourage open communication with their children and be careful not to bias them against their “ex” or use them as a means of hurting their “ex” (Denham, 2013; Harvey & Fine, 2004; Pescosoido, 2013).

A “Gray Divorce Revolution”?

In 2013 Brown and Lin referred to a “gray divorce revolution”. The figures certainly seem to support their contention. The rate of divorce had doubled for those aged 50-64 in the twenty years between 1990 and 2010. One in 10 persons who divorced in 1990 was over age 50, by 2010 it was over 1 in 4, accounting for some 25% of all divorces in the USA. Various explanations have been offered for this phenomenon. The “baby boomers” had divorced in large numbers in early adulthood, and a large number of remarriages within this group also ended in divorce. Remarriages are about 2.5 times more likely to end in divorce than first marriages. People are living longer and are no longer satisfied with relationships deemed insufficient to meet their emotional needs. The shift to companionate marriage in the latter half of the 20th century had followed this segment of the population into midlife, with divorce rates diminishing or stabilizing for other segments of the population.

Socio-emotional selectivity theory would predict that the shift of perspective from time spent to time remaining would predict people valuing experiences and relationships in the present, rather than holding onto memories of the past, or an idealized vision of what might yet come to be. Nevertheless, Cohen (2018) predicts a substantial decline in divorce rates for those who are not part of the “baby boom” generation, and that marriage rates will stabilize once more in subsequent generational cohorts. There has been a marked decline in divorce rates for those under 45 and the link between college education and marriage is now quite pronounced. People are now waiting until later in life to marry for the first time. The average age is now 27 for women and 29 for men, and it is even higher in urban centers like NYC. However, Reeves et al (2016) show that just over half of women with high school diplomas in their 40s are married, with the figures rising to 75% of those women with Bachelors’s degrees. Increasing economic insecurity may have played a part in ensuring that marriage may increasingly be correlated with educational attainment and socioeconomic status rather than cohorts based solely on age.

U.S. households are now increasingly single-person households. The number is reckoned to be more than 28% of all households and may become the most common form soon if trends in Europe are anything to go by. There, the number of one-person households in countries and Denmark and Germany exceeds 40%, with other major European countries like France not far from reaching that proportion. The number of Americans who are unmarried continues to increases. About 45% of all Americans over the age of 18 are unmarried, in 1960 that number was 28% (US Census, 2017). Around 1 in 4 young adults in the USA, today will never marry (Pew, 2014). The diversity of households will continue to increase. Currently, the number of one-person households in Japan and Germany is double that of households with children under 18.

Remarriage and Repartnering

Middle adulthood seems to be the prime time for remarriage, as the Pew Research Center reported in 2014 that of those aged between 55-64 who had previously been divorced, 67% had remarried. In 1960, it was 55%. Every other age category reported declines in the number of remarriages. Notably, remarriage is more popular with men than women, a gender gap that not only persists but grows substantially in middle and later adulthood. Cohabitation is the main way couples prepare for remarriage, but even when living together, many important issues are still not discussed. Issues concerning money, ex-spouses, children, visitation, future plans, previous difficulties in marriage, etc. can all pose problems later in the relationship. Few couples engage in premarital counseling or other structured efforts to cover this ground before entering into marriage again.

The divorce rate for second marriages is reckoned to be in excess of 60%, and for third marriages even higher. There is little research in the area of repartnering and remarriage, and the choices and decisions made during the process. A notable exception is that of Brown et al (2019) who offer an overview of the little that there is, and their own conclusions. One important constraint which they note is that men prefer younger women, at least as far as remarriage is concerned. Indeed, the age gap is often more pronounced in second marriages than in the first, according to Pew (2014). Allied to the fact that women live, on average, five years longer in the USA, then the pool of available partners shrinks for women. Brown et al (2019), also argue that this is further reinforced by the fact that women have a preference for retaining their autonomy and not playing the role of caregiver again. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of their research is the fact that those who repartner tend to do so quickly, and that longer-term singles are more likely to remain so.

Reviews are mixed as to how happy remarriages are. Some say that they have found the right partner and have learned from mistakes. But the divorce rates for remarriages are higher than for first marriages. This is especially true in stepfamilies for reasons which we have already discussed. People who have remarried tend to divorce more quickly than those first marriages. This may be due to the fact that they have fewer constraints on staying married (are more financially or psychologically independent).

Factors Affecting Remarriage

The chances of remarrying depend on several things. First, it depends on the availability of partners. As time goes by, there are more available women than men in the marriage pool as noted above. Consequently, men are more likely than women to remarry. This lack of available partners is experienced by all women, but especially by African-American women where the ratio of women to men is quite high. Women are more likely to have children living with them, and this diminishes the chance of remarriage as well. And marriage is more attractive for males than females (Seccombe & Warner, 2004). Men tend to remarry sooner (3 years after divorce on average vs. 5 years on average for women).

Many women do not remarry because they do not want to remarry. Traditionally, marriage has provided more benefits to men than to women. Women typically have to make more adjustments in work (accommodating work life to meet family demands or the approval of the husband) and at home (taking more responsibility for household duties). Education increases men’s likelihood of remarrying but may reduce the likelihood for women. Part of this is due to the expectation (almost an unspoken rule) referred to as the “marriage gradient.” This rule suggests among couples, the man is supposed to have more education than the woman. Today, there are more women with higher levels of education than before and women with higher levels are less likely to find partners matching this expectation. Being happily single requires being economically self-sufficient and being psychologically independent. Women in this situation may find remarriage much less attractive.

One key factor in understanding some of these issues is the level of continuing parental investment in adult children, and possibly their children. The number of grandparents raising children in the USA is reckoned to be in the vicinity of 2.7 million. In addition, there is the continued support of adult children themselves which can be substantial. The Pew Research document “Helping Adult Children” (2015) gives some indication of the nature and extent of this support, which tends to be even greater in Europe than the USA, with 60% of Italian parents reporting an adult child residing with them most of the year.

Blended Families

Most academic research on reconstituted or blended families focuses on younger adults and the kind of difficulties that ensue when trying to blend children raised by a different spouse/partner and one or more adults with perhaps different views or experiences on how this might be accomplished. All sorts of issues can arise: conflicted loyalties, different attitudes to discipline, role ambiguity, and the simple fact of a far-reaching change easily perceived as a disruption on the part of a child. Given the rise of the gray divorce, it is increasingly the case that this age group will encounter later age, or adult children (sometimes called the “boomerang generation”), in the house of their new partners. Such encounters are even more likely given the rise of the so-called “silver surfer” utilizing online dating sites and the fact that an increasing number of adult children continue to live at home given the increased cost of housing.

There has not been substantial research on recoupling and blended families in later life, but Papernow (2018) notes that all of the factors normally in play with younger children can be just as present, and even exacerbated, by the fact that previous relationships have had an even longer time to grow and solidify. In addition, stepfamilies formed in later life may have very difficult and complicated decisions to make about estate planning and elder care, as well as navigating daily life together, as an increasing number of young adults live at home (“grown but not gone”). Papernow lists five challenges for later-life stepfamilies:

- Stepparents are stuck as outsiders, while parents are the insiders in their relationships with their families.

- Stepchildren struggle with the change, even as adults, as they navigate new dynamics in family gatherings, status, and loyalty issues

- Parenting and discipline issues polarize the parents and stepparents. In general, stepparents want more discipline and are viewed as harsher, while parents want more understanding and are viewed more as the pushover. There are often disagreements about how much support (financial, physical, and emotional) to give older children.

- Stepfamilies must build a new family culture, even after there are already at least two established family cultures coming together.

- Ex-spouses are still part of a stepfamily, and children, even adult children, are worse off when they have involved in the conflict between their parent’s ex-spouses.