Learning Objectives

- Describe the situations under which [glossary_exclude]social facilitation[/glossary_exclude] and [glossary_exclude]social inhibition[/glossary_exclude] might occur, and review the theories that have been used to explain these processes.

- Explain the influence of each of these concepts on group performance: [glossary_exclude]groupthink[/glossary_exclude], information sharing, brainstorming, and [glossary_exclude]group polarization[/glossary_exclude].

When important decisions need to be made, or when tasks need to be performed quickly or effectively, we frequently create groups to accomplish them. Many people believe that groups are effective for making decisions and performing other tasks (Nijstad, Stroebe, & Lodewijkx, 2006), and such a belief seems commonsensical. After all, because groups have many members, they will also have more resources and thus more ability to efficiently perform tasks and make good decisions. However, although groups sometimes do perform better than individuals, this outcome is not guaranteed. Let’s consider some of the many variables that can influence group performance.

Social Facilitation and Social Inhibition

In one of the earliest social psychological studies, Norman Triplett (1898) investigated how bicycle racers were influenced by the social situation in which they raced. Triplett found something very interesting—the racers who were competing with other bicyclers on the same track rode significantly faster than bicyclers who were racing alone, against the clock. This led Triplett to hypothesize that people perform tasks better when the social context includes other people than when they do the tasks alone. Subsequent findings validated Triplett’s results, and other experiments have shown that the presence of others can increase performance on many types of tasks, including jogging, shooting pool, lifting weights, and working on math and computer problems (Geen, 1989; Guerin, 1983; Robinson-Staveley & Cooper, 1990; Strube, Miles, & Finch, 1981). The tendency to perform tasks better or faster in the presence of others is known as social facilitation.

Although people sometimes perform better when they are in groups than they do alone, the situation is not that simple. Perhaps you can remember a time when you found that a task you could perform well alone (e.g., giving a public presentation, playing the piano, shooting basketball free throws) was not performed as well when you tried it with, or in front of, others. Thus it seems that the conclusion that being with others increases performance cannot be entirely true and that sometimes the presence of others can worsen our performance. The tendency to perform tasks more poorly or slower in the presence of others is known as social inhibition.

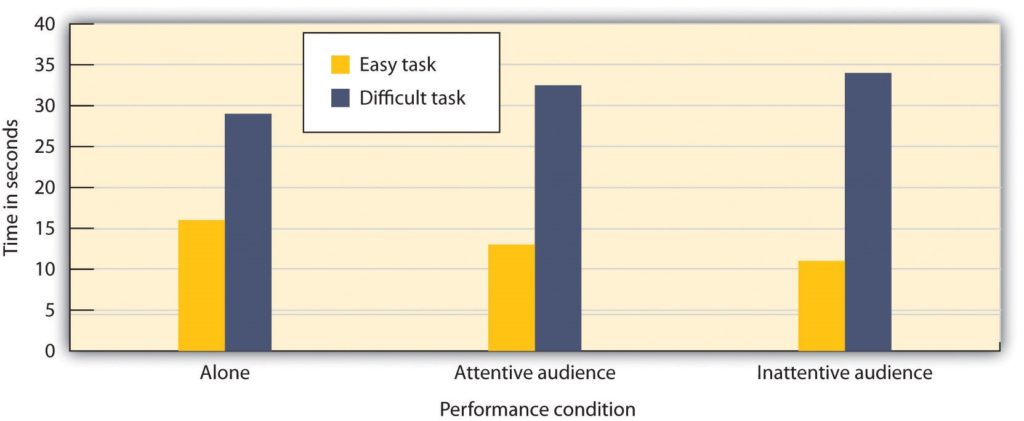

To study social facilitation and social inhibition, Hazel Markus (1978) gave research participants both an easy task (putting on and tying their shoes) and an unfamiliar and thus more difficult task (putting on and tying a lab coat that tied in the back). The research participants were asked to perform both tasks in one of three social situations—alone, with a confederate present who was watching them, or with a confederate present who sat in the corner of the room repairing a piece of equipment without watching. As you can see in Figure 11.2 “Group Task Performance”, Markus found first that the difficult task was performed more slowly overall. But she also found an interaction effect, such that the participants performed the easy task faster but the more difficult task slower when a confederate was present in the room. Furthermore, it did not matter whether the other person was paying attention to their performance or whether the other person just happened to be in the room working on another task—the mere presence of another person nearby influenced performance.

These results convincingly demonstrated that working around others could either help or hinder performance. But why would this be? One explanation of the influence of others on task performance was proposed by Robert Zajonc (1965). As shown in Figure 11.3 “Explaining Social Facilitation and Social Inhibition”, Zajonc made use of the affective component of arousal in his explanation. Zajonc argued that when we are with others, we experience more arousal than we do when we are alone, and that this arousal increases the likelihood that we will perform the dominant response—the action that we are most likely to emit in any given situation.

The important aspect of Zajonc’s theory was that the experience of arousal and the resulting increase in the performance of the dominant response could be used to predict whether the presence of others would produce social facilitation or social inhibition. Zajonc argued that if the task to be performed was relatively easy, or if the individual had learned to perform the task very well (a task such as pedaling a bicycle or tying one’s shoes), the dominant response was likely to be the correct response, and the increase in arousal caused by the presence of others would improve performance. On the other hand, if the task was difficult or not well learned (e.g., solving a complex problem, giving a speech in front of others, or tying a lab apron behind one’s back), the dominant response was likely to be the incorrect one; and because the increase in arousal would increase the occurrence of the (incorrect) dominant response, performance would be hindered.

Zajonc’s theory explained how the presence of others can increase or decrease performance, depending on the nature of the task, and a great deal of experimental research has now confirmed his predictions. In a meta-analysis, Bond and Titus (1983) looked at the results of over 200 studies using over 20,000 research participants and found that the presence of others did significantly increase the rate of performance on simple tasks and decrease both the rate and the quality of performance on complex tasks.

One interesting aspect of Zajonc’s theory is that because it only requires the concepts of arousal and dominant response to explain task performance, it predicts that the effects of others on performance will not necessarily be confined to humans. Zajonc reviewed evidence that dogs ran faster, chickens ate more feed, ants built bigger nests, and rats had more sex when other dogs, chickens, ants, and rats, respectively, were around (Zajonc, 1965). In fact, in one of the most unusual of all social psychology experiments, Zajonc, Heingartner, and Herman (1969) found that cockroaches ran faster on straight runways when other cockroaches were observing them (from behind a plastic window) but that they ran slower, in the presence of other roaches, on a maze that involved making a difficult turn, presumably because running straight was the dominant response, whereas turning was not.

Although the arousal model proposed by Zajonc is perhaps the most elegant, other explanations have also been proposed to account for social facilitation and social inhibition. One modification argues that we are particularly influenced by others when we perceive that the others are evaluating us or competing with us (Szymanski & Harkins, 1987). This is often called evaluation apprehension.

This makes sense because in these cases, another important motivator of human behavior—the desire to enhance the self—is involved in addition to arousal. In one study supporting this idea, Strube and his colleagues (Strube, Miles, & Finch, 1981) found that the presence of spectators increased the speed of joggers only when the spectators were facing the joggers and thus could see them and assess their performance.

The presence of others who expect us to do well and who are thus likely to be particularly distracting has been found to have important consequences in some real-world situations.

When people do not work as hard in a group as they do when they are alone is known as social loafing (Karau & Williams, 1993).

Losses Due to Group Conformity Pressures: Groupthink

Groups can make effective decisions only when they are able to make use of the advantages that come with group membership. These advantages include the ability to pool the information that is known to each of the members and to test out contradictory ideas through group discussion. Group decisions can be better than individual decisions only when the group members act carefully and rationally—considering all the evidence and coming to an unbiased, fair, and open decision. However, these conditions are not always met in real groups.

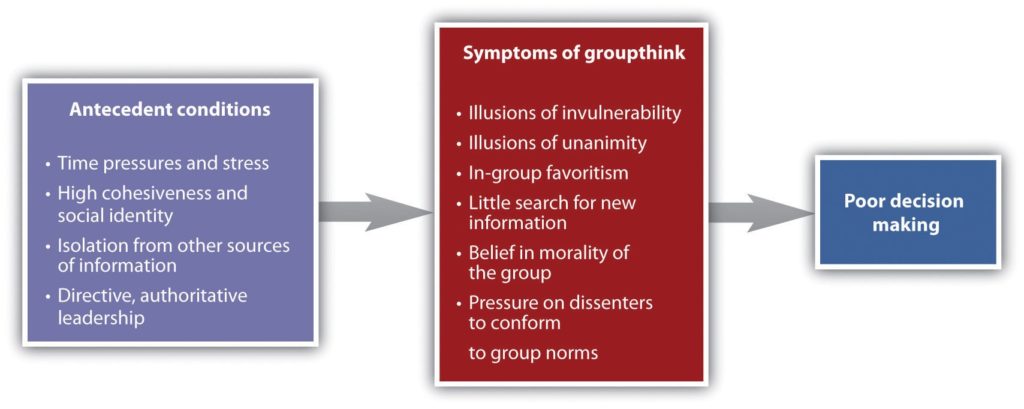

As we saw in the chapter opener, one example of a group process that can lead to very poor group decisions is groupthink. Groupthink occurs when a group that is made up of members who may actually be very competent and thus quite capable of making excellent decisions nevertheless ends up making a poor one as a result of a flawed group process and strong conformity pressures (Baron, 2005; Janis, 2007). Groupthink is more likely to occur in groups in which the members are feeling strong social identity—for instance, when there is a powerful and directive leader who creates a positive group feeling, and in times of stress and crisis when the group needs to rise to the occasion and make an important decision. The problem is that groups suffering from groupthink become unwilling to seek out or discuss discrepant or unsettling information about the topic at hand, and the group members do not express contradictory opinions. Because the group members are afraid to express ideas that contradict those of the leader or to bring in outsiders who have other information, the group is prevented from making a fully informed decision. Figure 11.6 “Antecedents and Outcomes of Groupthink” summarizes the basic causes and outcomes of groupthink.

Although at least some scholars are skeptical of the importance of groupthink in real group decisions (Kramer, 1998), many others have suggested that groupthink was involved in a number of well-known and important, but very poor, decisions made by government and business groups. Decisions analyzed in terms of groupthink include the decision to invade Iraq made by President George W. Bush and his advisers; the decision of President John Kennedy and his advisers to commit U.S. forces to help with an invasion of Cuba, with the goal of overthrowing Fidel Castro in 1962; and the lack of response to warnings on an attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, in 1941.

Careful analyses of the decision-making process in these cases have documented the role of conformity pressures. In fact, the group process often seems to be arranged to maximize the amount of conformity rather than to foster free and open discussion. In the meetings of the Bay of Pigs advisory committee, for instance, President Kennedy sometimes demanded that the group members give a voice vote regarding their individual opinions before the group actually discussed the pros and cons of a new idea. The result of these conformity pressures is a general unwillingness to express ideas that do not match the group norm.

The pressures for conformity also lead to the situation in which only a few of the group members are actually involved in conversation, whereas the others do not express any opinions. Because little or no dissent is expressed in the group, the group members come to believe that they are in complete agreement. In some cases, the leader may even select individuals (known as mindguards) whose job it is to help quash dissent and to increase conformity to the leader’s opinions.

An outcome of the high levels of conformity found in these groups is that the group begins to see itself as extremely valuable and important, highly capable of making high-quality decisions, and invulnerable. In short, the group members develop extremely high levels of conformity and social identity. Although this social identity may have some positive outcomes in terms of a commitment to work toward group goals (and it certainly makes the group members feel good about themselves), it also tends to result in illusions of invulnerability, leading the group members to feel that they are superior and that they do not need to seek outside information. Such a situation is conducive to terrible decision making and resulting fiascos.

Group Polarization

One common task of groups is to come to a consensus regarding a judgment or decision, such as where to hold a party, whether a defendant is innocent or guilty, or how much money a corporation should invest in a new product. Whenever a majority of members in the group favors a given opinion, even if that majority is very slim, the group is likely to end up adopting that majority opinion. Of course, such a result would be expected, since, as a result of conformity pressures, the group’s final judgment should reflect the average of group members’ initial opinions.

Although groups generally do show pressures toward conformity, the tendency to side with the majority after group discussion turns out to be even stronger than this. It is commonly found that groups make even more extreme decisions, in the direction of the existing norm, than we would predict they would, given the initial opinions of the group members. Group polarization is said to occur when, after discussion, the attitudes held by the individual group members become more extreme than they were before the group began discussing the topic (Brauer, Judd, & Gliner, 2006; Myers, 1982).

Because the group as a whole is taking responsibility for the decision, the individual may be willing to take a more extreme stand, since he or she can share the blame with other group members if the risky decision does not work out.

Group polarization does not occur in all groups and in all settings but tends to happen when two conditions are present: First, the group members must have an initial leaning toward a given opinion or decision. If the group members generally support liberal policies, their opinions are likely to become even more liberal after discussion. But if the group is made up of both liberals and conservatives, group polarization would not be expected. Second, group polarization is strengthened by discussion of the topic. For instance, in the research by Myers and Kaplan (1976) just reported, in some experimental conditions the group members expressed their opinions but did not discuss the issue, and these groups showed less polarization than groups that discussed the issue.

Group polarization has also been observed in important real-world contexts, including financial decision-making in group and corporate boardrooms (Cheng & Chiou, 2008; Zhu, 2010), and it may also occur in other situations. It has been argued that the recent polarization in political attitudes in the United States (the “blue” Democratic states versus the “red” Republican states) is occurring in large part because each group spends time communicating with other like-minded group members, leading to more extreme opinions on each side. And it has been argued that terrorist groups develop their extreme positions and engage in violent behaviors as a result of the group polarization that occurs in their everyday interactions (Drummond, 2002; McCauley, 1989). As the group members, all of whom initially have some radical beliefs, meet and discuss their concerns and desires, their opinions polarize, allowing them to become progressively more extreme. Because they are also away from any other influences that might moderate their opinions, they may eventually become mass killers.

Group polarization is the result of both cognitive and affective factors. The general idea of the persuasive arguments approach to explaining group polarization is cognitive in orientation. This approach assumes is that there is a set of potential arguments that support any given opinion and another set of potential arguments that refute that opinion. Furthermore, an individual’s current opinion about the topic is predicted to be based on the arguments that he or she is currently aware of. During group discussion, each member presents arguments supporting his or her individual opinions. And because the group members are initially leaning in one direction, it is expected that there will be many arguments generated that support the initial leaning of the group members. As a result, each member is exposed to new arguments supporting the initial leaning of the group, and this predominance of arguments leaning in one direction polarizes the opinions of the group members (Van Swol, 2009). Supporting the predictions of persuasive arguments theory, research has shown that the number of novel arguments mentioned in discussion is related to the amount of polarization (Vinokur & Burnstein, 1978) and that there is likely to be little group polarization without discussion (Clark, Crockett, & Archer, 1971).

But group polarization is in part based on the affective responses of the individuals—and particularly the social identity they receive from being good group members (Hogg, Turner, & Davidson, 1990; Mackie, 1986; Mackie & Cooper, 1984). The idea here is that group members, in their desire to create positive social identity, attempt to differentiate their group from other implied or actual groups by adopting extreme beliefs. Thus the amount of group polarization observed is expected to be determined not only by the norms of the ingroup but also by a movement away from the norms of other relevant outgroups. In short, this explanation says that groups that have well-defined (extreme) beliefs are better able to produce social identity for their members than are groups that have more moderate (and potentially less clear) beliefs.

Group polarization effects are stronger when the group members have high social identity (Abrams, Wetherell, Cochrane, & Hogg, 1990; Hogg, Turner, & Davidson, 1990; Mackie, 1986). Diane Mackie (1986) had participants listen to three people discussing a topic, supposedly so that they could become familiar with the issue themselves to help them make their own decisions. However, the individuals that they listened to were said to be members of a group that they would be joining during the upcoming experimental session, members of a group that they were not expecting to join, or some individuals who were not a group at all. Mackie found that the perceived norms of the (future) ingroup were seen as more extreme than those of the other group or the individuals, and that the participants were more likely to agree with the arguments of the ingroup. This finding supports the idea that group norms are perceived as more extreme for groups that people identify with (in this case, because they were expecting to join it in the future). And another experiment by Mackie (1986) also supported the social identity prediction that the existence of a rival outgroup increases polarization as the group members attempt to differentiate themselves from the other group by adopting more extreme positions.

Taken together then, the research reveals that another potential problem with group decision making is that it can be polarized. These changes toward more extreme positions have a variety of causes and occur more under some conditions than others, but they must be kept in mind whenever groups come together to make important decisions.

Chapter Summary

Groups are also more effective when they develop appropriate social norms—for instance, norms about sharing information. Information is more likely to be shared when the group has plenty of time to make its decision. The group leader is extremely important in fostering norms of open discussion.

Perhaps the most straightforward approach to getting people to work harder in groups is to provide rewards for performance. This approach is frequently, but not always, successful. People also work harder in groups when they feel that they are contributing to the group and that their work is visible to and valued by the other group members.

One aspect of planning that has been found to be strongly related to positive group performance is the setting of goals that the group uses to guide its work. Groups that set specific, difficult, and yet attainable goals perform better. In terms of group diversity, there are both pluses and minuses. Although diverse groups may have some advantages, the groups—and particularly the group leaders—must work to create a positive experience for the group members.

Your new knowledge about working groups can help you in your everyday life. When you find yourself in a working group, be sure to use this information to become a better group member and to make the groups you work in more productive.

Adapted from “Chapter 11.2: Group Process: The Pluses and Minuses of Working Together” of Principles of Social Psychology, 2015, used according to creative commons CC BY-NC-SA 4.0