In this section, we will address techniques you can use to communicate your opinions, rights, expectations and boundaries. We will also look at the relationship between culture, co-culture, and power, and at some ways in which power is often misused in intimate relationships.

12.4.1: Effective Communication: Communicating Opinions, Rights, Expectations, and Boundaries

Since power dynamics influence our interactions and relationships, we may find ourselves in positions where we have less power or perceive we have less power. In these situations, it is important to know how to effectively communicate our opinions, rights, expectations, and boundaries. Below we provide some strategies you can use:

|

Be assertive, not passive or aggressive. Assertive communication carries respect for the feelings, needs, wants, and opinions of others. An assertive communicator avoids infringing upon the rights of others, while asserting their own, and seeking compromise or collaboration in the process. Assertive communication utilizes actions and words to express opinions, rights, expectations, and boundaries in a calm fashion, while conveying a message of confidence and respect.[1] When communicating assertively, you should not make sarcastic or condescending remarks, blame the other, shout, threat, or name call. |

|

Don’t be silent if you have something to say. |

|

Identify what your needs are. |

|

Say “no” when appropriate. · Keep it brief. For example, if you don’t have time to do a favor, you can simply say, “I can’t this time. Sorry to disappoint you, but I have too many things to do that day, and there’s no room in my schedule.” Also, if someone asks you a question that you don’t want to answer, it okay to say something like “I don’t really feel comfortable answering that.” |

|

Have confident body language. |

12.4.2: Contextual Communication: Culture, Co-Culture, and Power

Power is also influenced by culture and co-culture. As mentioned in Chapter 2: Culture and Communication, all cultures consist of a dominant group and nondominant group. Group memberships and identities, such as gender and race, can work to advantage one particular group of people while simultaneously disadvantaging another to create unequal power dynamics and oppression. Such actions are accomplished, as discussed below, through labeling, othering, and stereotyping. Also covered below is ways in which ideologies operate to mask these inequalities.

12.4.2.1: Labeling, Othering, and Stereotyping:

The dominant group engages in exercises of power that reflect their interests and help to perpetuate inequalities in power and status. Systems of power and domination are maintained at a cultural and co-cultural level through labeling, othering, and stereotyping. The labels attached to people seen as ‘minorities’ have always been defined by the white majority—that is, by those with power. Defining an individual primarily in terms of their apparent racial or ethnic identity—for example, with labels such as black or Asian—is a way of defining them as ‘different’ from a supposed white ‘norm.’ Othering is accomplished by creating an insider/outsider narrative where whiteness is the criteria for normal; you are either white or non-white. The same can be said of attaching labels to people on the basis of a supposed disability, sexual preference, or age. In addition, stereotyping makes broad generalizations about groups and people based on their co-cultural membership and identities. Often, these stereotypes are negative, since they reflect the differential power between those in the ‘majority’ and those categorized as ‘minorities’ or ‘different.’ So, for example, women may be defined as less rational than men, or black people as less intelligent than white people; in these instances, men and white people respectively are characterized as the ‘norm.’ These negative stereotypes both reflect and perpetuate existing inequalities—patterns of sexism and racism in society. An example would be denying women and people of color access to jobs that require a ‘cool head’ or complex intellectual skills. In other words, stereotyping people as ‘different’ often leads to prejudice and discrimination. Attributing these fixed ‘differences’ to people is not a neutral process, but is one that both reflects and reproduces inequalities of power and status.

12.4.2.2: Ideologies:

Another way we see power maintained and normalized at a cultural level is through the use of ideologies and values. In the United States, there are many overlapping ideologies that create the illusion that inequality linked to co-cultural categories, such as race or social class, do not exist. For example, a prevalent U.S. American ideology is the Achievement Ideology which is the belief that any person can be successful through hard work and education and that disadvantaged individuals need to “pull themselves up by their bootstraps.” This ideology disadvantages particular groups by placing the blame of success or failure on the individual rather than looking at institutional and systemic inequality—or, “lack of bootstraps.” For example, K-12 educational institutions have become increasingly segregated by race and social class, and, as such, students who attend certain schools don’t have access to the same quality of educational resources as another group may have. Unequal access impacts academic performance and makes some students more likely to attain high grades or perform well on the college admissions tests necessary to get into universities (Orfield and Frankenberg’s, 2014). In addition, inside the classroom, it is the dominant group’s behaviors and values that have been normalized. These norms determine what a successful student looks and acts like, as well as how they are evaluated in assessments like tests and papers (Bennett & Lecompte, 1990; Lesdesma & Caldera, 2005). Students who violate teacher expectations for “normal” behavior face consequences and are “judged by teachers to be less academically able (Bennett & LeCompte, 1990, p. 16).” Such treatment disadvantages low income and students of color who may have different, conflicting, or even contradictory cultural norms and values. People of color and ESL students are also more likely than their white counterparts to be tracked into remedial courses and thus they do not receive the same quality of education. These types of systemic inequalities in K-12 education hold long-term implications for the success of these groups

12.4.3: Reflective Communication: Misuses of Power in Intimate Relationships

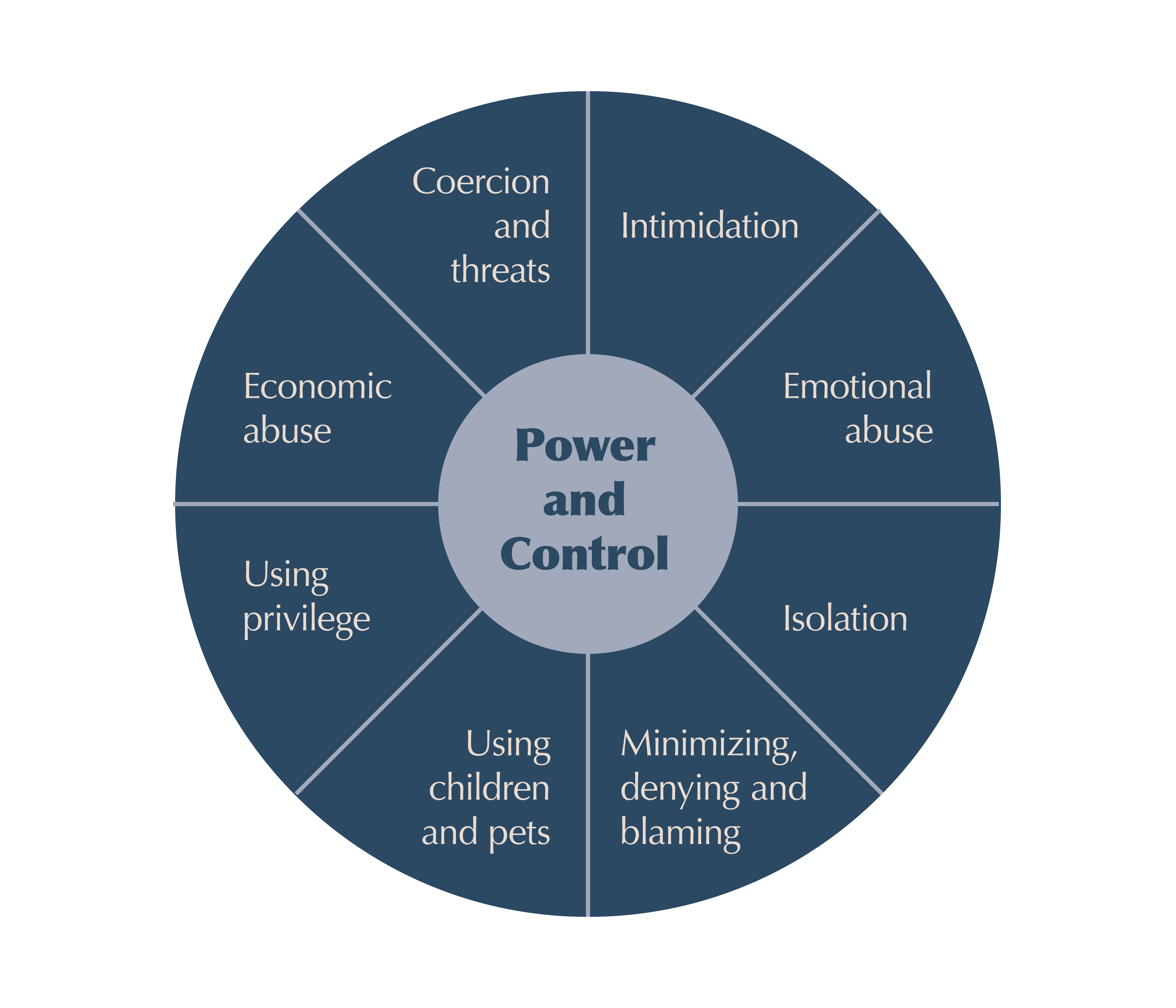

Generally, healthy relationships contain a relative balance of power between participants. Unhealthy relationships occur when there are imbalances of power and one participant tries to control or take advantage of the other. This is accomplished by using abusive power to gain and maintain control and subject that person to psychological, physical, sexual, or financial abuse. The goal of the abuser is to control and intimidate the victim or to influence them to feel that they do not have an equal voice in the relationship[2] and abusers usually to try normalize, legitimize, rationalize, deny, minimize the abusive behavior, or blame the victim for it.[7][8][9] Controlling abusers use multiple tactics to exert power and control over their partners. Because each of the tactics are used to maintain power in the relationship, it is important to become familiar with the tactics below in order to avoid being part of an unhealthy relationship, or to help and educate others.

- Coercion and Threats:

Threats and coercion are tools for exerting control and power. Abusers may threaten to leave, hurt others, or even threaten suicide. They may also coerce others to perform illegal actions or to drop charges against their abusers. [36] At its most powerful, the abuser creates intimidation and fear through unpredictable and inconsistent behavior.[6]

- Intimidation:

Abused individuals may be intimidated by the brandishing of weapons—for example, threatening to use a gun or simply displaying the weapon. Other forms of intimidation include destruction of property or other things, or use of gestures or looks to create fear.[36]

- Economic Abuse:

Controlling someone’s access to money is another means of ensuring control and power over another. One method is to prevent the other from getting or retaining a job. Other ways to control access to money are: withholding information and access to family income, taking a person’s money, requiring the person to ask for money, giving someone an allowance, or filing a power of attorney or conservatorship—particularly in the case of economic abuse of the elderly.[36]

- Emotional Abuse:

Emotional abuse includes name-calling, mind games, putting the victim down, or humiliating the individual. The goals are to make the person feel bad about themselves, feel guilty or think that they are crazy.[36]

- Isolation:

Another element of psychological control is the isolation of the victim from the outside world.[33] Isolation includes controlling a person’s social activity—who they see, who they talk to, where they go, and any other method that limits access to others. It may include limiting what material is read, insisting on knowing where the victim is at all times, and requiring permission for medical care. The abuser might also exhibit hypersensitive and reactive jealousy.[33]

- Minimizing, Denying, and Blaming:

An abuser may deny that any abuse occurred in order to place the responsibility for their behavior on the victim. Another example of this type of control is when the abuser minimizes the victim’s concerns or denies the degree of abuse. [36]

- Using Children and Pets:

Children may be also be used to exert control. Abusers threaten to take the children or make the other feel guilty about the children. Abusers may harass children during visitation or use the children to relay messages. Abusing pets is another controlling tactic. [36]

- Using Privilege:

Using “privilege” means that the abuser defines the roles in the relationship, makes the important decisions, treats the individual like a servant, and acts like the “master of the castle”.[36]