Is all behavior learned from the environment? Should psychology, as science, focus on observable behavior—the result of stimulus-response, as opposed to internal events like thinking and emotion? Is there little difference between the learning that takes place in humans and that in other animals? These are types of questions considered by behaviorists, which we’ll learn more about in this section. We’ll also consider cognitive theories, which examine the construction of thought processes, including remembering, problem-solving, and decision-making, from childhood through adolescence to adulthood.

Exploring Behavior

The Behavioral Perspective: A Focus on Observable Behavior

The behavioral perspective is the psychological approach that suggests that the keys to understanding development are observable behavior and external stimuli in the environment. Behaviorism is a theory of learning, and learning theories focus on how we respond to events or stimuli rather than emphasizing internal factors that motivate our actions. These theories provide an explanation of how experience can change what we do.

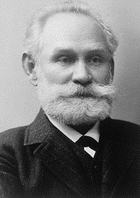

Behaviorism emerged early in the 20th century and became a major force in American psychology. Championed by psychologists such as John B. Watson (1878–1958) and B. F. Skinner (1904–1990), behaviorism rejected any reference to the mind and viewed overt and observable behavior as the proper subject matter of psychology. Through the scientific study of behavior, it was hoped that laws of learning could be derived that would promote the prediction and control of behavior. Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov (1849–1936) influenced early behaviorism in America. His work on conditioned learning, popularly referred to as classical conditioning, provided support for the notion that learning and behavior were controlled by events in the environment and could be explained with no reference to mind or consciousness (Fancher, 1987).

Classical Conditioning and Emotional Responses

Classical conditioning theory helps us to understand how our responses to one situation become attached to new situations. For example, a smell might remind us of a time when we were a kid. If you went to a new cafe with the same smell as your elementary cafeteria, it might evoke the feelings you had when you were in school. Or a song on the radio might remind you of a memorable evening you spent with your first true love. Or, if you hear your entire name (Isaiah Wilmington Brewer, for instance) called as you walk across the stage to get your diploma and it makes you tense because it reminds you of how your father used to use your full name when he was mad at you, then you’ve been classically conditioned.

Figure 1. Ivan Pavlov

Classical conditioning explains how we develop many of our emotional responses to people or events or our “gut level” reactions to situations. New situations may bring about an old response because the two have become connected. Attachments form in this way. Addictions are affected by classical conditioning, as anyone who’s tried to quit smoking can tell you. When you try to quit, everything that was associated with smoking makes you crave a cigarette.

Pavlov and Classical Conditioning

Ivan Pavlov (1849–1936) was a Russian physiologist interested in studying digestion. As he recorded the amount of salivation his laboratory dogs produced as they ate, he noticed that they actually began to salivate before the food arrived as the researcher walked down the hall and toward the cage. “This,” he thought, “is not natural!” One would expect a dog to automatically salivate when the food hit their palate, but before the food comes? Of course, what happened is that the dogs knew the food was coming because they had learned to associate the footsteps with the food. The keyword here is “learned.”

A learned response is called a “conditioned” response. Pavlov began to experiment with this “psychic” reflex. He began to ring a bell, for instance, prior to introducing the food. Sure enough, after making this connection several times, the dogs could be made to salivate to the sound of a bell. Once the bell had become an event to which the dogs had learned to salivate, it was called a conditioned stimulus. The act of salivating to a bell was a response that had also been learned, now termed in Pavlov’s jargon, a conditioned response. Notice that the response, salivation, is the same whether it is conditioned or unconditioned (unlearned or natural). What changed is the stimulus to which the dog salivates. One is natural (unconditioned) and one is learned (conditioned).

Figure 2. Before conditioning, an unconditioned stimulus (food) produces an unconditioned response (salivation), and a neutral stimulus (bell) does not produce a response. During conditioning, the unconditioned stimulus (food) is presented repeatedly just after the presentation of the neutral stimulus (bell). After conditioning, the neutral stimulus alone produces a conditioned response (salivation), thus becoming a conditioned stimulus.

Watson and Behaviorism

Let’s think about how classical conditioning is used on people, and not just with dogs. One of the most widespread applications of classical conditioning principles was brought to us by the psychologist, John B. Watson. Watson proposed that the process of classical conditioning (based on Pavlov’s observations) was able to explain all aspects of human psychology. He established the psychological school of behaviorism, after doing research on animal behavior. This school was extremely influential in the middle of the 20th century when B.F. Skinner developed it further.

Watson believed that most of our fears and other emotional responses are classically conditioned. He gained a good deal of popularity in the 1920s with his expert advice on parenting offered to the public. He believed that parents could be taught to help shape their children’s behavior and tried to demonstrate the power of classical conditioning with his famous experiment with an 18-month-old boy named “Little Albert.” Watson sat Albert down and introduced a variety of seemingly scary objects to him: a burning piece of newspaper, a white rat, etc. But Albert remained curious and reached for all of these things. Watson knew that one of our only inborn fears is the fear of loud noises so he proceeded to make a loud noise each time he introduced one of Albert’s favorites, a white rat. After hearing the loud noise several times paired with the rat, Albert soon came to fear the rat and began to cry when it was introduced.

Watson filmed this experiment for posterity and used it to demonstrate that he could help parents achieve any outcomes they desired if they would only follow his advice. Watson wrote columns in newspapers and in magazines and gained a lot of popularity among parents eager to apply science to household order. However, parenting advice was not the legacy Watson left us, where he really made his impact was in advertising. After Watson left academia, he went into the world of business and showed companies how to tie something that brings about a natural positive feeling to their products to enhance sales. Thus the union of sex and advertising!

Operant Conditioning

Now, we turn to the second type of associative learning, operant conditioning. In operant conditioning, organisms learn to associate a behavior and its consequence (Table 1). A pleasant consequence makes that behavior more likely to be repeated in the future. For example, Spirit, a dolphin at the National Aquarium in Baltimore, does a flip in the air when her trainer blows a whistle. The consequence is that she gets a fish.

Psychologist B. F. Skinner saw that classical conditioning is limited to existing behaviors that are reflexively elicited, and it doesn’t account for new behaviors such as riding a bike. He proposed a theory about how such behaviors come about. Skinner believed that behavior is motivated by the consequences we receive for the behavior: the reinforcements and punishments. His idea that learning is the result of consequences is based on the law of effect, which was first proposed by psychologist Edward Thorndike. According to the law of effect, behaviors that are followed by consequences that are satisfying to the organism are more likely to be repeated, and behaviors that are followed by unpleasant consequences are less likely to be repeated (Thorndike, 1911). Essentially, if an organism does something that brings about a desired result, the organism is more likely to do it again. If an organism does something that does not bring about a desired result, the organism is less likely to do it again. An example of the law of effect is in employment. One of the reasons (and often the main reason) we show up for work is because we get paid to do so. If we stop getting paid, we will likely stop showing up—even if we love our job.

Working with Thorndike’s law of effect as his foundation, Skinner began conducting scientific experiments on animals (mainly rats and pigeons) to determine how organisms learn through operant conditioning (Skinner, 1938). He placed these animals inside an operant conditioning chamber, which has come to be known as a “Skinner box” (Figure ). A Skinner box contains a lever (for rats) or disk (for pigeons) that the animal can press or peck for a food reward via the dispenser. Speakers and lights can be associated with certain behaviors. A recorder counts the number of responses made by the animal.

Figure 3. (a) B. F. Skinner developed operant conditioning for the systematic study of how behaviors are strengthened or weakened according to their consequences. (b) In a Skinner box, a rat presses a lever in an operant conditioning chamber to receive a food reward. (credit a: modification of work by “Silly rabbit”/Wikimedia Commons)

Skinner believed that we learn best when our actions are reinforced. For example, a child who cleans his room and is reinforced (rewarded) with a big hug and words of praise is more likely to clean it again than a child whose deed goes unnoticed. Skinner believed that almost anything could be reinforcing. A reinforcer is anything following a behavior that makes it more likely to occur again. It can be something intrinsically rewarding (called intrinsic or primary reinforcers), such as food or praise, or it can be something that is rewarding because it can be exchanged for what one really wants (such as receiving money and using it to buy a cookie). Such reinforcers are referred to as secondary reinforcers.

Comparing Classical and Operant Conditioning

| Table 1. Classical and Operant Conditioning Compared | ||

| Classical Conditioning | Operant Conditioning | |

| Conditioning approach | An unconditioned stimulus (such as food) is paired with a neutral stimulus (such as a bell). The neutral stimulus eventually becomes the conditioned stimulus, which brings about the conditioned response (salivation). | The target behavior is followed by reinforcement or punishment to either strengthen or weaken it so that the learner is more likely to exhibit the desired behavior in the future. |

| Stimulus timing | The stimulus occurs immediately before the response. | The stimulus (either reinforcement or punishment) occurs soon after the response. |

Social Cognitive (Learning) Theory: Observational Learning

Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), originally known as the Social Learning Theory (SLT), began in the 1960s through research done by Albert Bandura. The theory proposes that learning occurs in a social context. It takes into consideration the dynamic and reciprocal interaction of the person, environment, and their own behavior.

Not all forms of learning are accounted for entirely by classical and operant conditioning. Imagine a child walking up to a group of children playing a game on the playground. The game looks fun, but it is new and unfamiliar. Rather than joining the game immediately, the child opts to sit back and watch the other children play a round or two. Observing the others, the child takes note of the ways in which they behave while playing the game. By watching the behavior of the other kids, the child can figure out the rules of the game and even some strategies for doing well at the game. This is called observational learning.

Observational learning is a component of Albert Bandura’s Social Learning Theory (Bandura, 1977), which posits that individuals can learn novel responses via observation of key others’ behaviors. Observational learning does not necessarily require reinforcement, but instead hinges on the presence of others, referred to as social models. Social models are normally of higher status or authority compared to the observer, examples of which include parents, teachers, and police officers. In the example above, the children who already know how to play the game could be thought of as being authorities—and are therefore social models—even though they are the same age as the observer. By observing how the social models behave, an individual is able to learn how to act in a certain situation. Other examples of observational learning might include a child learning to place her napkin in her lap by watching her parents at the dinner table, or a customer learning where to find the ketchup and mustard after observing other customers at a hot dog stand.

Bandura theorizes that the observational learning process consists of four parts. The first is attention—one must pay attention to what they are observing in order to learn. The second part is retention: to learn one must be able to retain the behavior they are observing in memory. The third part of observational learning, initiation, acknowledges that the learner must be able to execute (or initiate) the learned behavior. Lastly, the observer must possess the motivation to engage in observational learning. In our vignette, the child must want to learn how to play the game in order to properly engage in observational learning.

In this experiment, Bandura (Bandura, Ross, & Ross, 1961) had children individually observe an adult social model interact with a clown doll (Bobo). For one group of children, the adult interacted aggressively with Bobo: punching it, kicking it, throwing it, and even hitting it in the face with a toy mallet. Another group of children watched the adult interact with other toys, displaying no aggression toward Bobo. In both instances, the adult left and the children were allowed to interact with Bobo on their own. Bandura found that children exposed to the aggressive social model were significantly more likely to behave aggressively toward Bobo, hitting and kicking him, compared to those exposed to the non-aggressive model. The researchers concluded that the children in the aggressive group used their observations of the adult social model’s behavior to determine that aggressive behavior toward Bobo was acceptable.

While reinforcement was not required to elicit the children’s behavior in Bandura’s first experiment, it is important to acknowledge that consequences do play a role within observational learning. A future adaptation of this study (Bandura, Ross, & Ross, 1963) demonstrated that children in the aggression group showed less aggressive behavior if they witnessed the adult model receive punishment for aggressing against Bobo. Bandura referred to this process as vicarious reinforcement because the children did not experience the reinforcement or punishment directly yet were still influenced by observing it.

Do parents socialize children or do children socialize parents?

Bandura’s (1986) findings suggest that there is interplay between the environment and the individual. We are not just the product of our surroundings, rather we influence our surroundings. There is interplay between our personality and the way we interpret events and how they influence us. This concept is called reciprocal determinism. An example of this might be the interplay between parents and children. Parents not only influence their child’s environment, perhaps intentionally through the use of reinforcement, etc., but children influence parents as well. Parents may respond differently to their first child than with their fourth. Perhaps they try to be the perfect parents with their firstborn, but by the time their last child comes along, they have very different expectations of themselves and their child. Our environment creates us and we create our environment. Today there are numerous other social influences, from TV, games, the Internet, i-Pads, phones, social media, influencers, advertisements, etc.

Exploring Cognition

The Cognitive Perspective: The Roots of Understanding

Cognitive theories focus on how our mental processes or cognitions change over time. The theory of cognitive development is a comprehensive theory about the nature and development of human intelligence first developed by Jean Piaget. It is primarily known as a developmental stage theory, but in fact, it deals with the nature of knowledge itself and how humans come gradually to acquire it, construct it, and use it. Moreover, Piaget claims that cognitive development is at the center of the human organism and language is contingent on cognitive development. Let’s learn more about Piaget’s views about the nature of intelligence and then dive deeper into the stages that he identified as critical in the developmental process.

Piaget: Changes in thought with maturation

Figure 5. Jean Piaget.

Jean Piaget (1896-1980) is one of the most influential cognitive theorists in development, inspired to explore children’s ability to think and reason by watching his own children’s development. He was one of the first to recognize and map out the ways in which children’s intelligence differs from that of adults. He became interested in this area when he was asked to test the IQ of children and began to notice that there was a pattern in their wrong answers. He believed that children’s intellectual skills change over time that that maturation rather than training brings about that change. Children of differing ages interpret the world differently.

Making sense of the world

Piaget believed that we are continuously trying to maintain cognitive equilibrium or a balance or cohesiveness in what we see and what we know. Children have much more of a challenge in maintaining this balance because they are constantly being confronted with new situations, new words, new objects, etc. When faced with something new, a child may either fit it into an existing framework (schema) and match it with something known (assimilation) such as calling all animals with four legs “doggies” because he or she knows the word doggie, or expand the framework of knowledge to accommodate the new situation (accommodation) by learning a new word to more accurately name the animal. This is the underlying dynamic in our own cognition. Even as adults we continue to try to make sense of new situations by determining whether they fit into our old way of thinking or whether we need to modify our thoughts.

Stages of Cognitive Development

Like Freud and Erikson, Piaget thought development unfolded in a series of stages approximately associated with age ranges. He proposed a theory of cognitive development that unfolds in four stages: sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operational, and formal operational.

| Age (years) | Stage | Description | Developmental issues |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–2 | Sensorimotor | World experienced through senses and actions | Object permanence Stranger anxiety |

| 2–7 | Preoperational | Use words and images to represent things but lack logical reasoning | Pretend play Egocentrism Language development |

| 7–11 | Concrete operational | Understand concrete events and logical analogies; perform arithmetical operations | Conservation Mathematical transformations |

| 11– | Formal operational | Utilize abstract reasoning and hypothetical thinking | Abstract logic Moral reasoning |

The first stage, the sensorimotor stage, lasts from birth to about 2 years old. During this stage, children learn about the world through their senses and motor behavior. Young children put objects in their mouths to see if the items are edible, and once they can grasp objects, they may shake or bang them to see if they make sounds. Between 5 and 8 months old, the child develops object permanence, which is the understanding that even if something is out of sight, it still exists (Bogartz, Shinskey, & Schilling, 2000). According to Piaget, young infants do not remember an object after it has been removed from sight. Piaget studied infants’ reactions when a toy was first shown to an infant and then hidden under a blanket. Infants who had already developed object permanence would reach for the hidden toy, indicating that they knew it still existed, whereas infants who had not developed object permanence would appear confused.

In Piaget’s view, around the same time children develop object permanence, they also begin to exhibit stranger anxiety, which is a fear of unfamiliar people. Babies may demonstrate this by crying and turning away from a stranger, by clinging to a caregiver, or by attempting to reach their arms toward familiar faces such as parents. Stranger anxiety results when a child is unable to assimilate the stranger into an existing schema; therefore, she can’t predict what her experience with that stranger will be like, which results in a fear response.

Piaget’s second stage is the preoperational stage, which is from approximately 2 to 7 years old. In this stage, children can use symbols to represent words, images, and ideas, which is why children in this stage engage in pretend play. A child’s arms might become airplane wings as he zooms around the room, or a child with a stick might become a brave knight with a sword. Children also begin to use language in the preoperational stage, but they cannot understand adult logic or mentally manipulate information (the term operational refers to logical manipulation of information, so children at this stage are considered to be pre-operational). Children’s logic is based on their own personal knowledge of the world so far, rather than on conventional knowledge. For example, Dad gave a slice of pizza to 10-year-old Keiko and another slice to her 3-year-old brother, Kenny. Kenny’s pizza slice was cut into five pieces, so Kenny told his sister that he got more pizza than she did. Children in this stage cannot perform mental operations because they have not developed an understanding of conservation, which is the idea that even if you change the appearance of something, it is still equal in size as long as nothing has been removed or added.

During this stage, we also expect children to display egocentrism, which means that the child is not able to take the perspective of others. A child at this stage thinks that everyone sees, thinks, and feels just as they do. Let’s look at Kenny and Keiko again. Keiko’s birthday is coming up, so their mom takes Kenny to the toy store to choose a present for his sister. He selects an Iron Man action figure for her, thinking that if he likes the toy, his sister will too. An egocentric child is not able to infer the perspective of other people and instead attributes his own perspective. At some point during this stage typically between 3 and 5 years old, children come to understand that people have thoughts, feelings, and beliefs that are different from their own. This is known as theory-of-mind (TOM).

Piaget’s third stage is the concrete operational stage, which occurs from about 7 to 11 years old. In this stage, children can think logically about real (concrete) events; they have a firm grasp on the use of numbers and start to employ memory strategies. They can perform mathematical operations and understand transformations, such as addition is the opposite of subtraction, and multiplication is the opposite of division. In this stage, children also master the concept of conservation: Even if something changes shape, its mass, volume, and number stay the same. For example, if you pour water from a tall, thin glass to a short, fat glass, you still have the same amount of water. Remember Keiko, Kenny, and the pizza? How did Keiko know that Kenny was wrong when he said that he had more pizza?

Children in the concrete operational stage also understand the principle of reversibility, which means that objects can be changed and then returned back to their original form or condition. Take, for example, water that you poured into the short, fat glass: You can pour water from the fat glass back to the thin glass and still have the same amount (minus a couple of drops).

The fourth, and last, stage in Piaget’s theory is the formal operational stage, which is from about age 11 to adulthood. Whereas children in the concrete operational stage are able to think logically only about concrete events, children in the formal operational stage can also deal with abstract ideas and hypothetical situations. Children in this stage can use abstract thinking to problem solve, look at alternative solutions, and test these solutions. In adolescence, a renewed egocentrism occurs. For example, a 15-year-old with a very small pimple on her face might think it is huge and incredibly visible, under the mistaken impression that others must share her perceptions.

Criticisms of Piaget’s Theory

As with other major contributors to theories of development, several of Piaget’s ideas have come under criticism based on the results of further research. For example, several contemporary studies support a model of development that is more continuous than Piaget’s discrete stages (Courage & Howe, 2002; Siegler, 2005, 2006). Many others suggest that children reach cognitive milestones earlier than Piaget describes (Baillargeon, 2004; de Hevia & Spelke, 2010). Looking across cultures reveals considerable variation in what children are able to do at various ages, and Piaget may have underestimated what children are capable of given the right circumstances.

According to Piaget, the highest level of cognitive development is formal operational thought, which develops between 11 and 20 years old. However, many developmental psychologists disagree with Piaget, suggesting a fifth stage of cognitive development, known as the postformal stage (Basseches, 1984; Commons & Bresette, 2006; Sinnott, 1998). In postformal thinking, decisions are made based on situations and circumstances, and logic is integrated with emotion as adults develop principles that depend on contexts. One way that we can see the difference between an adult in postformal thought and an adolescent (or adult) in formal operations is in terms of how they handle emotionally charged issues or integrate systems of thought.

It seems that once we reach adulthood our problem-solving abilities change: As we attempt to solve problems, we tend to think more deeply about many areas of our lives, such as relationships, work, and politics (Labouvie-Vief & Diehl, 1999). Because of this, postformal thinkers are able to draw on past experiences to help them solve new problems. Problem-solving strategies using postformal thought vary, depending on the situation. What does this mean? Adults can recognize, for example, that what seems to be an ideal solution to a problem at work involving a disagreement with a colleague may not be the best solution to a disagreement with a significant other.

Information-Processing Approaches to Development

Information-processing approaches have become an important alternative to Piagetian approaches. The theory is based on the idea that humans process the information they receive, rather than merely responding to stimuli. As a model, it assumes that even complex behavior such as learning, remembering, categorizing, and thinking can be broken down into a series of individual, specific steps, and as a person develops strategies for processing information, they can learn more complex information. This perspective equates the mind to a computer, which is responsible for analyzing information from the environment.

The most common information-processing model is applied to an understanding of memory and the way that information is encoded, stored, and then retrieved from the brain (Atkinson & Shiffrin, 1968), but information processing approaches also apply to cognitive processing in general. In one study, Stephanie Thornton assessed how children solved the problem of building a small bridge out of playing blocks to cross a small “river.” A single block was not wide enough to reach across the river, so the bridge could only be built by having two of the blocks meet in the middle, then by using extra blocks on the top of the sides of the bridge to serve as counterweights to hold the bridge upright. This task was relatively easy for older children (7 and 9 years old), but significantly harder for 5-year-olds (in the study, only one 5-year-old eventually completed the task by using trial and error). This supports the idea that cognitive development is specific to the individual.

Psychologists who use information processing approaches examine how children tackle tasks such as the ones described above, whether it be through trial and error, building upon previous life experiences, or generalizing insights from external sources.

Neo-Piagetian Theories

Some of the information processing approaches that build upon Piaget‘s research are known as neo-Piagetian theories. In contrast to Piaget‘s original work, which identified cognition as a single system of increasingly sophisticated general cognitive abilities, neo-Piagetian theories view cognition as a made up of different types of individual skills. Using the same terminology as information processing approaches, neo-Piagetian theories advance the idea that cognitive development proceeds quickly in certain areas and more slowly in others. Consider for example, our reading abilities and all the skills that are needed to recall stories. These abilities and skills may progress sooner than the abstract computational abilities used in algebra or trigonometry. Also, neo-Piagetian theorists believe that experience plays a greater role in furthering cognitive development than traditional Piagetian approaches claim. Neo-Piagetians also adopted principles from other theories, such as the social-cognitive theory that allowed them to consider how culture and interactions with others influenced cognitive development.

Cognitive Neuroscience Approaches

The scientific interface between cognitive neuroscience and human development has evoked considerable interest in recent years, as technological advances make it possible to map in detail the changes in brain structure that take place during development. These approaches look at cognitive development at the level of brain processes. Cognitive neuroscience is the scientific field that is concerned with the study of the biological processes and aspects that underlie cognition, with a specific focus on the neural connections in the brain which are involved in mental processes.

Like other cognitive perspectives, cognitive neuroscience approaches consider internal, mental processes, but they focus specifically on the neurological activity that underlies thinking, problem-solving, and other cognitive behavior. Cognitive neuroscientists seek to identify actual locations and functions within the brain that are related to different types of cognitive activities. For example, using sophisticated brain scanning techniques, cognitive neuroscientists have demonstrated that thinking about the meaning of a word activates different areas of the brain than thinking about how the word sounds when spoken.

Also, cognitive abilities based on brain development are studied and examined under the subfield of developmental cognitive neuroscience. It examines how the mind changes as children grow up, interrelations between that and how the brain is changing, and environmental and biological influences on the developing mind and brain. This shows brain development over time, analyzing differences and concocting possible reasons for those differences.