How the Obama Campaign Effectively Used Persuasion to Defeat John McCain

In ads and speeches, President Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign used a variety of persuasion techniques, many based on principles of social psychology. The campaign’s outcome was that millions of voters joined Obama’s team and helped him defeat his opponent, Senator John McCain. Many of the “Obama for America” ads were online, in stark contrast to the more traditional media used by the McCain campaign.

Obama’s campaign used a range of techniques, including cognitive and emotional persuasive appeals and attitude inoculation. The campaign focused in part on self-interest, trying to reach voters who were feeling the pinch of high gas prices. In some of the online ads, Senator McCain was pictured next to a list of high gas station prices while a fuel pump moved across the ad. The idea was that Obama would be seen as a clean candidate promoting clean energy while McCain was labeled as accepting contributions from the oil industry.

Obama also tapped into the strong human desire for other-concern. In his speeches he talked about being part of an important group that would make a difference, thereby creating strong social identity and positive emotions. Examples were his use of slogans such as “Yes We Can,” “We Believe,” and “Join Us.”

Obama also made use of attitude inoculation, a technique in which he warned his supporters that an ad attacking him would be coming, at the same time reminding them of ways to counterargue the ad. Obama argued, for instance, “What they’re going to try to do is make you scared of me. They’ll say ‘He’s not patriotic enough, he’s got a funny name…he’s young and inexperienced.” Obama hoped that people would be motivated to discount these messages when they came from McCain.

The techniques that were used by the Obama team are not unique—they are used by most contemporary advertisers, and also by attorneys, negotiators, corporate executives, and anyone else who wants to be an effective persuader—but they were masterfully employed by “Obama for America.”

Sources: Whitman, D. E. (2010). Cashvertising. Career Press; Kaye, Kate (2008). Obama targets Pennsylvania voters with pure persuasion ads. Personal Democracy Forum. Retrieved from http://techpresident.com/blog-entry/obama-targets-pennsylvania-voters-pure-persuasion-ads.

One of the most central concepts in social psychology is that of attitudes (Banaji & Heiphetz, 2010). In this chapter we will focus on attitude formation, attitude change, and the influence of attitudes on behavior. We will see that attitudes are an essential component of our lives because they play a vital role in helping us effectively interact with our environment. Our attitudes allow us to make judgments about events (“I hate waiting in traffic”), people (“I really like Barack Obama”), social groups (“I love the University of Maryland”), and many other things.

We will begin our discussion by looking at how attitudes are defined by the ABCs of social psychology—affect, behavior, and cognition—noting that some attitudes are more affective in nature, some more cognitive in nature, and some more behavioral in nature. We will see that attitudes vary in terms of their strength such that some attitudes are stronger and some are weaker. And we will see that the strength of our attitudes is one of the determinants of when our attitudes successfully predict our behaviors.

Then we will explore how attitudes can be created and changed—the basic stuff of persuasion, advertising, and marketing. We will look at which types of communicators can deliver the most effective messages to which types of message recipients. And we will see that the same message can be more effective for different people in different social situations. We will see that persuasive messages may be processed either spontaneously (that is, in a rather cursory or superficial way) or thoughtfully (with more cognitive elaboration of the message) and that the amount and persistence of persuasion will vary on the processing route that we use. Most generally, we will see that persuasion is effective when the communication resonates with the message recipient’s motivations, desires, and goals (Kruglanski & Stroebe, 2005).

Because the ABCs of social psychology tend to be consistent, persuasive appeals that change our thoughts and feelings will be effective in changing our behavior as well. This attitude consistency means that if I make you think and feel more positively about my product, then you will be more likely to buy it. And if I can make you think and feel more positively about my political candidate, then you will be more likely to vote for him or her.

But attitude consistency works in the other direction too, such that when our behaviors change, our thoughts and beliefs about the attitude object may also change. Once we vote for a candidate or buy a product, we will find even more things to like about them, and our attitudes toward them will become even more positive. Although this possibility is less intuitive and therefore may seem more surprising, it also follows from the basic consistencies among affect, cognition, and behavior. We will discuss two theories—self-perception theory and cognitive dissonance theory—each of which makes this prediction but for different reasons.

Creating Effective Communications

An important factor is to determine what type of message we deliver. Neither social psychologists nor advertisers are so naïve as to think that simply presenting a strong message is sufficient. No matter how good the message is, it will not be effective unless people pay attention to it, understand it, accept it, and incorporate it into their self-concept. This is why we attempt to choose good communicators to present our ads in the first place, and why we tailor our communications to get people to process them the way we want them to.

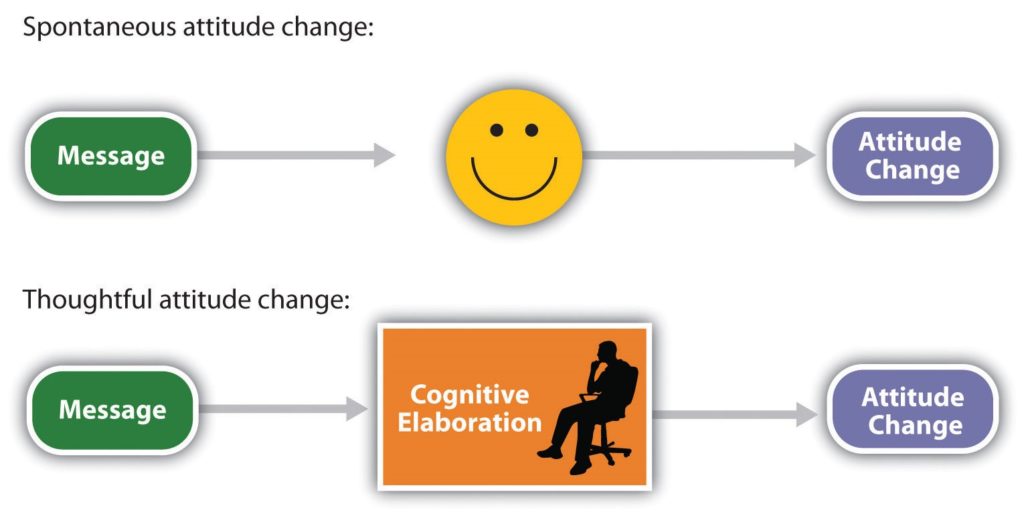

The messages that we deliver may be processed either spontaneously (other terms for this include peripherally or heuristically—Chen & Chaiken, 1999; Petty & Wegener, 1999) or thoughtfully (other terms for this include centrally or systematically). Spontaneous processing is direct, quick, and often involves affective responses to the message. Thoughtful processing, on the other hand, is more controlled and involves a more careful cognitive elaboration of the meaning of the message (Figure 5.3). The route that we take when we process a communication is important in determining whether or not a particular message changes attitudes.

Spontaneous Message Processing

Because we are bombarded with so many persuasive messages—and because we do not have the time, resources, or interest to process every message fully—we frequently process messages spontaneously. In these cases, if we are influenced by the communication at all, it is likely that it is the relatively unimportant characteristics of the advertisement that will influence us, such as the attractiveness of the communicator or the music playing in the ad.

If we find the communicator cute, if the music in the ad puts us in a good mood, or if it appears that other people around us like the ad, then we may simply accept the message without thinking about it very much (Giner-Sorolla & Chaiken, 1997). In these cases, we engage in spontaneous message processing, in which we accept a persuasion attempt because we focus on whatever is most obvious or enjoyable, without much attention to the message itself. Shelley Chaiken (1980) found that students who were not highly involved in a topic, because it did not affect them personally, were more persuaded by a likeable communicator than by an unlikeable one, regardless of whether the communicator presented a good argument for the topic or a poor one. On the other hand, students who were more involved in the decision were more persuaded by the better than by the poorer message, regardless of whether the communicator was likeable or not—they were not fooled by the likeability of the communicator.

You might be able to think of some advertisements that are likely to be successful because they create spontaneous processing of the message by basing their persuasive attempts around creating emotional responses in the listeners. In these cases the advertisers use association learning to associate the positive features of the ad with the product. Television commercials are often humorous, and automobile ads frequently feature beautiful people having fun driving beautiful cars. The slogans “The joy of cola!” “Coke adds life!” and “Be a Pepper!” are good ads in part because they successfully create positive affect in the listener.

In some cases emotional ads may be effective because they lead us to watch or listen to the ad rather than simply change the channel or doing something else. The clever and funny TV ads that are shown during the Super Bowl broadcast every year are likely to be effective because we watch them, remember them, and talk about them with others. In this case the positive affect makes the ads more salient, causing them to grab our attention. But emotional ads also take advantage of the role of affect in information processing. We tend to like things more when we are in good moods, and—because positive affect indicates that things are OK—we process information less carefully when we are in good moods. Thus the spontaneous approach to persuasion is particularly effective when people are happy (Sinclair, Mark, & Clore, 1994), and advertisers try to take advantage of this fact.

Association Learning

Association learning occurs when an object or event comes to be associated with a natural response, such as an automatic behavior or a positive or negative emotion. If you’ve ever become hungry when you drive by one of your favorite pizza stores, it is probably because the sight of the pizzeria has become associated with your experiences of enjoying the pizzas. We may enjoy smoking cigarettes, drinking coffee, and eating not only because they give us pleasure themselves but also because they have been associated with pleasant social experiences in the past.

Association learning also influences our knowledge and judgments about other people. For instance, research has shown that people view men and women who are seen alongside other people who are attractive, or who are said to have attractive girlfriends or boyfriends, more favorably than they do the same people who are seen alongside more average-looking others (Sigall & Landy, 1973). This liking is due to association learning—we have positive feelings toward the people simply because those people are associated with the positive features of the attractive others.

Association learning (classical conditioning) has long been, and continues to be, an effective tool in marketing and advertising (Hawkins, Best, & Coney, 1998). The general idea is to create an advertisement that has positive features so that it creates enjoyment in the person exposed to it. Because the product being advertised is mentioned in the ad, it becomes associated with the positive feelings that the ad creates. In the end, if everything has gone well, seeing the product online or in a store will then create a positive response in the buyer, leading him or her to be more likely to purchase the product.

For instance, if people enjoy watching a college basketball team playing basketball, and if that team is sponsored by a product, such as Pepsi, then people may end up experiencing positive feelings when they view a can of Pepsi. Of course, the sponsor wants to sponsor only good teams and good athletes because these create more pleasurable responses.

Advertisers use a variety of techniques to create positive advertisements, including enjoyable music, cute babies, attractive models, and funny spokespeople. In one study, Gorn (1982) showed research participants pictures of writing pens of different colors, but paired one of the pens with pleasant music and another with unpleasant music. When given a choice as a free gift, more people chose the pen that had been associated with the pleasant music. In another study, Schemer, Matthes, Wirth, and Textor (2008) found that people were more interested in products that had been embedded in music videos of artists that they liked and less likely to be interested when the products were in videos featuring artists that they did not like.

Another type of ad that is based on principles of classical conditioning is one that associates fear with the use of a product or behavior, such as those that show pictures of deadly automobile accidents to encourage seatbelt use or images of lung cancer surgery to discourage smoking. These ads have also been found to be effective (Das, de Wit, & Stroebe, 2003; Perloff, 2003; Witte & Allen, 2000), largely because of conditioning.

Recently, the U.S. government created new negative and graphic images to place on cigarette packs in order to increase an association between negative responses and cigarettes. The idea is that when we see a cigarette and the fear of dying is associated with it, we will be less likely to light up.

Taken together then, research studies provide ample evidence of the utility of associational learning in advertising, in ads using positive stimuli and in those using negative stimuli. This does not mean, however, that we are always influenced by these ads. The likelihood that association learning will be successful is greater when we do not know much about the products, where the differences between products are relatively minor, and when we do not think too carefully about the choices (Schemer et al., 2008).

Association learning is also implicated in the development of unfair and unjustified racial prejudices. We may dislike people from certain racial or ethnic groups because we frequently see them portrayed in the media as associated with violence, drug use, or terrorism. And we may avoid people with certain physical characteristics simply because they remind us of other people we do not like.

Lewicki (1985) conducted research that demonstrated the influence of association learning and how quickly and easily such learning can happen. In his experiment, high school students first had a brief interaction with a female experimenter who had short hair and wore glasses. The study was set up so that the students had to ask the experimenter a question, and (according to random assignment) the experimenter responded in either a negative way or a neutral way toward the participants. Then the students were told to go into a second room in which two experimenters were present and to approach either one of them. The researchers arranged it so that one of the two experimenters looked a lot like the original experimenter and the other one did not (she had longer hair and did not wear glasses). The students were significantly more likely to avoid the experimenter who looked like the original experimenter when that experimenter had been negative to them than when she had treated them neutrally. As a result of associational learning, the negative behavior of the first experimenter unfairly “rubbed off” onto the second.

Donal Carlston and his colleagues (Mae & Carlston, 2005; Skowronski, Carlston, Mae, & Crawford, 1998) discovered still another way that association learning can occur: When we say good or bad things about another person in public, the people who hear us say these things associate those characteristics with us, such that they like people who say positive things and dislike people who say negative things. The moral is clear—association learning is powerful, so be careful what you do and say

Fear Appeals

Another type of ad that is based on emotional responses is the one that uses fear appeals, such as ads that show pictures of deadly automobile accidents to encourage seatbelt use or images of lung cancer surgery to decrease smoking. By and large, fearful messages are persuasive (Das, de Wit, & Stroebe, 2003; Perloff, 2003; Witte & Allen, 2000). Again, this is due in part to the fact that the emotional aspects of the ads make them salient and lead us to attend to and remember them. And fearful ads may also be framed in a way that leads us to focus on the salient negative outcomes that have occurred for one particular individual. When we see an image of a person who is jailed for drug use, we may be able to empathize with that person and imagine how we would feel if it happened to us. Thus this ad may be more effective than more “statistical” ads stating the base rates of the number of people who are jailed for drug use every year.

Fearful ads also focus on self-concern, and advertisements that are framed in a way that suggests that a behavior will harm the self are more effective than the same messages that are framed more positively. Banks, Salovey, Greener, and Rothman (1995) found that a message that emphasized the negative aspects of not getting a breast cancer screening mammogram (“not getting a mammogram can cost you your life”) was more effective than a similar message that emphasized the positive aspects (“getting a mammogram can save your life”) in getting women to have a mammogram over the next year. These findings are consistent with the general idea that the brain responds more strongly to negative affect than it does to positive affect (Ito, Larsen, Smith, & Cacioppo, 1998).

Although laboratory studies generally find that fearful messages are effective in persuasion, they have some problems that may make them less useful in real-world advertising campaigns (Hastings, Stead, & webb, 2004). Fearful messages may create a lot of anxiety and therefore turn people off to the message (Shehryar & Hunt, 2005). For instance, people who know that smoking cigarettes is dangerous but who cannot seem to quit may experience particular anxiety about their smoking behaviors. Fear messages are more effective when people feel that they know how to rectify the problem, have the ability to actually do so, and take responsibility for the change. Without some feelings of self-efficacy, people do not know how to respond to the fear (Aspinwall, Kemeny, Taylor, & Schneider, 1991). Thus if you want to scare people into changing their behavior, it may be helpful if you also give them some ideas about how to do so, so that they feel like they have the ability to take action to make the changes (Passyn & Sujan, 2006).

Thoughtful Message Processing

When we process messages only spontaneously, our feelings are more likely to be important, but when we process messages thoughtfully, cognition prevails. When we care about the topic, find it relevant, and have plenty of time to spend thinking about the communication, we are likely to process the message more deliberatively, carefully, and thoughtfully (Petty & Briñol, 2008). In this case we elaborate on the communication by considering the pros and cons of the message and questioning the validity of the communicator and the message. Thoughtful message processing occurs when we think about how the message relates to our own beliefs and goals and involves our careful consideration of whether the persuasion attempt is valid or invalid.

When an advertiser presents a message that he or she hopes will be processed thoughtfully, the goal is to create positive cognitions about the attitude object in the listener. The communicator mentions positive features and characteristics of the product and at the same time attempts to downplay the negative characteristics. When people are asked to list their thoughts about a product while they are listening to, or right after they hear, a message, those who list more positive thoughts also express more positive attitudes toward the product than do those who list more negative thoughts (Petty & Briñol, 2008). Because the thoughtful processing of the message bolsters the attitude, thoughtful processing helps us develop strong attitudes, which are therefore resistant to counterpersuasion (Petty, Cacioppo, & Goldman, 1981).

Which Route Do We Take: Thoughtful or Spontaneous?

Both thoughtful and spontaneous messages can be effective, but it is important to know which is likely to be better in which situation and for which people. When we can motivate people to process our message carefully and thoughtfully, then we are going to be able to present our strong and persuasive arguments with the expectation that our audience will attend to them. If we can get the listener to process these strong arguments thoughtfully, then the attitude change will likely be strong and long lasting. On the other hand, when we expect our listeners to process only spontaneously—for instance, if they don’t care too much about our message or if they are busy doing other things—then we do not need to worry so much about the content of the message itself; even a weak (but interesting) message can be effective in this case. Successful advertisers tailor their messages to fit the expected characteristics of their audiences.

In addition to being motivated to process the message, we must also have the ability to do so. If the message is too complex to understand, we may rely on spontaneous cues, such as the perceived trustworthiness or expertise of the communicator and ignore the content of the message (Hafer, Reynolds, & Obertynski, 1996). When experts are used to attempt to persuade people—for instance, in complex jury trials—the messages that these experts give may be very difficult to understand. In these cases the jury members may rely on the perceived expertise of the communicator rather than his or her message, being persuaded in a relatively spontaneous way. In other cases we may not be able to process the information thoughtfully because we are distracted or tired—in these cases even weak messages can be effective, again because we process them spontaneously (Petty, Wells & Brock, 1976).

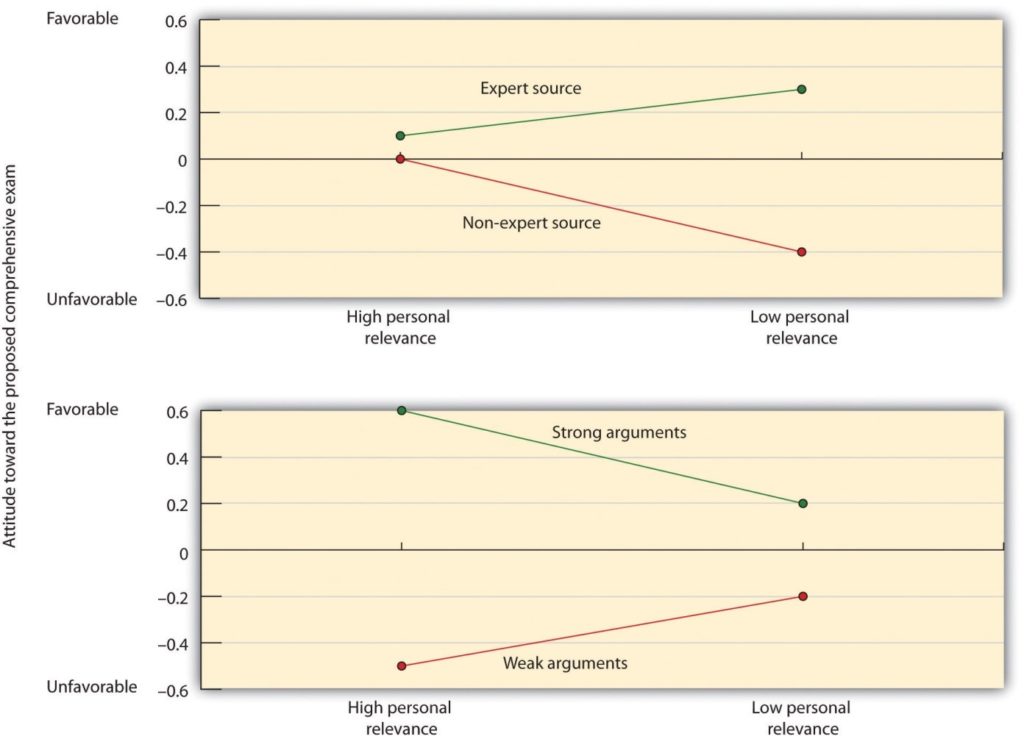

Petty, Cacioppo, and Goldman (1981) showed how different motivations may lead to either spontaneous or thoughtful processing. In their research, college students heard a message suggesting that the administration at their college was proposing to institute a new comprehensive exam that all students would need to pass in order to graduate and then rated the degree to which they were favorable toward the idea. The researchers manipulated three independent variables:

- Message strength. The message contained either strong arguments (persuasive data and statistics about the positive effects of the exams at other universities) or weak arguments (relying only on individual quotations and personal opinions).

- Source expertise. The message was supposedly prepared either by an expert source (the Carnegie Commission on Higher Education, which was chaired by a professor of education at Princeton University) or by a nonexpert source (a class at a local high school).

- Personal relevance. The students were told either that the new exam would begin before they graduated (high personal relevance) or that it would not begin until after they had already graduated (low personal relevance).

As you can see in Figure 5.4, Petty and his colleagues found two interaction effects. The top panel of the figure shows that the students in the high personal relevance condition (left side) were not particularly influenced by the expertise of the source, whereas the students in the low personal relevance condition (right side) were. On the other hand, as you can see in the bottom panel, the students who were in the high personal relevance condition (left side) were strongly influenced by the quality of the argument, but the low personal involvement students (right side) were not.

These findings fit with the idea that when the issue was important, the students engaged in thoughtful processing of the message itself. When the message was largely irrelevant, they simply used the expertise of the source without bothering to think about the message.

Petty, Cacioppo, and Goldman (1981) found that students for whom an argument was not personally relevant based their judgments on the expertise of the source (spontaneous processing), whereas students for whom the decision was more relevant were more influenced by the quality of the message (thoughtful processing).

Because both thoughtful and spontaneous approaches can be successful, advertising campaigns, such as those used by the Obama presidential campaign, carefully make use of both spontaneous and thoughtful messages. In some cases, the messages showed Obama smiling, shaking hands with people around him, and kissing babies; in other ads Obama was shown presenting his plans for energy efficiency and climate change in more detail.

Adapted from “Chapter 2.1: Sources of Social Knowledge”, “Chapter 5: Attitudes, Behavior, and Persuasion”, “Chapter 5.2: Changing Attitudes Through Persuasion” and “Chapter: 6.3 Individual and Cultural Differences in [glossary_exclude]Person Perception[/glossary_exclude]” of Principles of Social Psychology, 2015, used according to creative commons CC BY-NC-SA 4.0