As you’ll recall from chapter one, a channel is the means through which the message is sent from one communicator to the other. The channels used for communication coincide with our senses of sound, sight, smell, taste, and touch. While verbal messages can only travel via the sensory routes of sound (spoken words) or sight (written words), nonverbal communication can take place through all five of our senses. In this section, we will describe the various types of non-verbal communication, which we break into four distinct categories to aid in comprehension: body language, paralanguage, space and time use, and personal and environmental presentation.

6.3.1: Body Language

Body language refers to nonverbal communication that is expressed through the use of gestures, head movements and posture, eye contact, facial expressions, and touch.

Gestures:

There are three main types of gestures: adaptors, emblems, and illustrators (Andersen, 1999). Adaptors are touching behaviors and movements that indicate internal states typically related to arousal or anxiety. Adaptors can be targeted toward the self, objects, or others. In regular social situations, adaptors result from uneasiness, anxiety, or a general sense that we are not in control of our surroundings. Many of us subconsciously click pens, shake our legs, or engage in other adaptors during classes, meetings, or while waiting as a way to do something with our excess energy. Use of object adaptors can also signal boredom as people play with the straw in their drink or peel the label off a bottle of beer.

Emblems are gestures that have a specific agreed-on meaning. A hitchhiker’s raised thumb, the “OK” sign with thumb and index finger connected in a circle with the other three fingers sticking up, and the raised middle finger are all examples of emblems that have an agreed-upon meaning or meanings within a specific culture. Later in the chapter, you will see how different those agree-upon meanings can be among different cultures.

Illustrators are the most common type of gesture and are used to illustrate the verbal message they accompany. For example, you might use hand gestures to indicate the size or shape of an object. Unlike emblems, illustrators do not typically have meaning on their own and are used more subconsciously than emblems.

Head Movements and Posture:

Head movements and posture are grouped together because they are often both used to acknowledge others and communicate interest or attentiveness. For example, a head up typically indicates an engaged or neutral attitude, a head tilt indicates interest and is an innate submission gesture that exposes the neck and subconsciously makes people feel more trusting of us, and a head down signals a negative or aggressive attitude (Pease & Pease, 2004). One interesting standing posture involves putting our hands on our hips, and is a nonverbal cue that we use subconsciously to make us look bigger and show assertiveness.

Eye Contact:

Eye Contact: Eye contact can have a variety of meanings, based on culture, co-culture, and context. It can be used to show interest, respect, aggression, or even dislike. For example, what do you think it means when someone “mad dogs” another person or gives them the “stink eye”?

We also communicate through eye behaviors, primarily eye contact. Eye contact serves several communicative functions: regulating interaction, monitoring interaction, conveying information, or establishing interpersonal connections. In terms of regulating communication, we use eye contact to signal to others that we are ready to speak or to indicate that we are finishing up. Eye contact is also used to monitor interaction by taking in feedback and other nonverbal cues. A communicator can use eye contact to determine if others are engaged, confused, or bored and then adapt their message accordingly. Our eyes also send information to others. Making eye contact with others also communicates that we are paying attention and are interested in what another person is saying. Eye contact can also be used to intimidate others. Staring at another person in some contexts could communicate intimidation, while in other contexts it could communicate flirtation.

Facial Expressions:

Our faces are the most expressive part of our bodies. Facial expressions communicate a range of emotions and can be used to infer personality traits and make judgments about others. Facial expressions can communicate that someone is tired, excited, angry, confused, frustrated, sad, confident, smug, shy, or bored. A few basic facial expressions are recognizable by humans all over the world; research has supported the universality of a core group of facial expressions: happiness, sadness, fear, anger, and disgust. The first four are especially identifiable across cultures (Andersen, 1999).

Although facial expressions are typically viewed as innate and several are universally recognizable, they are not always connected to an emotional or internal biological stimulus; they can actually serve a more social purpose. For example, most of the smiles we produce are primarily made for others and are not just an involuntary reflection of an internal emotional state (Andersen, 1999).

Haptics:

Haptics refers to the study of communication by touch. Touch is necessary for human social development, and it can be welcoming, threatening, or persuasive. There are several types of touch, including functional-professional, social-polite, friendship-warmth, and love- intimacy (Heslin & Apler, 1983). At the functional-professional level, touch is related to a goal or part of a routine professional interaction, which makes it less threatening and more expected. For example, we let barbers, hairstylists, doctors, nurses, tattoo artists, and security screeners touch us in ways that would otherwise be seen as intimate or inappropriate if not in a professional context.

At the social-polite level, socially sanctioned touching behaviors help initiate interactions and show that others are included and respected. A handshake, a pat on the arm, and a pat on the shoulder are examples of social-polite touching. At the friendship-warmth level, touch is more important and more ambiguous than at the social-polite level. At this level, touch interactions are important because they serve a relational maintenance purpose and communicate closeness, liking, care, and concern. At the love- intimacy level, touch is more personal and is typically only exchanged between significant others, such as best friends, close family members, and romantic partners. Touching faces, holding hands, and frontal embraces are examples of touch at this level.

6.3.2: Paralanguage & Silence

Silence: Silence can be a powerful form of nonverbal communication. What does it usually mean if someone is giving you the “silent treatment”?

Paralanguage, often referred to as vocalics, refers to the vocalized but nonverbal parts of a message such as pitch, volume, rate, vocal quality, and verbal fillers (Andersen, 1999). Pitch helps convey meaning, regulate conversational flow, and communicate the intensity of a message. We also learn that greetings have a rising emphasis and farewells have falling emphasis. Of course, no one ever tells us these things explicitly; we learn them through observation and practice. We do not pick up on some more subtle and/or complex patterns of paralanguage involving pitch until we are older. Children, for example, have a difficult time perceiving sarcasm, which is usually conveyed through paralinguistic characteristics like pitch and tone rather than the actual words being spoken. Paralanguage provides important context for the verbal content of a message. For example, volume helps communicate intensity. A louder voice is usually thought of as more intense, although a soft voice combined with a certain tone and facial expression can be just as intense. Our tone of voice can be controlled somewhat with pitch, volume, and emphasis, but each voice has a distinct quality known as a vocal signature. Voices vary in terms of resonance, pitch, and tone, and some voices are more pleasing than others.

In addition, the use of silence serves as a type of nonverbal communication when we do not use words or utterances to convey meanings. Have you ever experienced the “silent treatment” from someone? What meanings did you take from that person’s silence? Silence is powerful because the person using silence may be refusing to engage in communication with you. Silence can also be used strategically in conversations, such as silent pause for emphasis or a long period of silence in response to another’s message. Others may use silence as a form of resistance. For example, silent protests or ‘days of silence’ are often used to show disapproval or bring awareness to a particular issue. It’s important to be aware that silence has a variety of interpretations and misinterpretations. For example, we may interpret another’s silence as intentional, even when it wasn’t. Or some people may remain silent to convey disagreement with something, however, others may interpret that silence as agreement.

6.3.3: Space, Territory, and Time

Other types of nonverbal communication types are: the way we use space around us, the territories we claim, and how we use time.

Spatial Use:

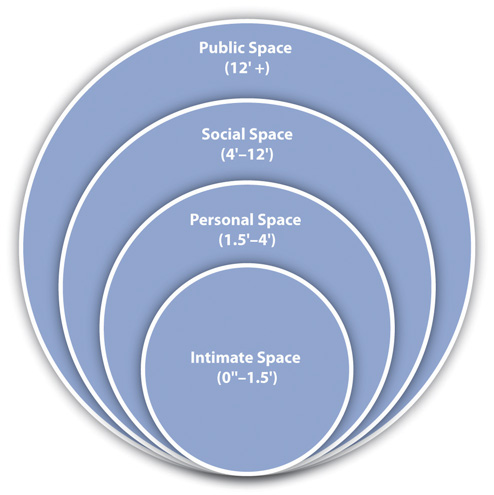

Spatial use, also called proxemics, refers to the study of how space and distance influence communication. In general, space influences how people communicate and behave. Smaller spaces with a higher density of people often lead to breaches of our personal space bubbles. Unexpected breaches of personal space can lead to negative reactions, especially if we feel someone has violated our space voluntarily, meaning that a crowding situation didn’t force them into our space. We all have varying definitions of what our “personal space” is, and these definitions are contextual and depend on the situation and the relationship.

Although our bubbles are invisible, people are socialized into the norms of personal space within their cultural group. Scholars have identified four zones for U.S. Americans, which are public, social, personal, and intimate distance (Hall, 1968). The zones are more elliptical than circular, taking up more space in our front, where our line of sight is, than at our side or back where we can’t monitor what people are doing. Even within a particular zone, interactions may differ depending on whether someone is in the outer or inner part of the zone.

Territoriality:

In addition to various notions of personal space, we claim spaces as our own, such as a gang territory, a neighborhood claimed by a particular salesperson, your usual desk in the classroom, or the seat you’ve marked to save while getting concessions at a sporting event. Territoriality is an innate drive to take up and defend spaces. There are three main divisions for territory: primary, secondary, and public (Hargie, 2011). Sometimes our claim to a space is official. These spaces are known as our primary territories because they are marked or understood to be exclusively ours and under our control. A person’s house, yard, room, desk, side of the bed, or shelf in the medicine cabinet could be considered primary territories. Secondary territories don’t belong to us and aren’t exclusively under our control. However, they are associated with us, which may lead us to assume that the space will be open and available to us when we need it without us taking any further steps to reserve it.

This happens in classrooms regularly. Students often sit in the same desk or at least same general area as they did on the first day of class. The expectation of this being “our space” could lead to a negative interpretation of the classmate you find sitting there one morning. Public territories are open to all people. People are allowed to mark public territory and use it for a limited period of time. This space is often up for grabs, though, which makes public space difficult to manage for some people, and can lead to conflict. To avoid this type of situation, people use a variety of objects that are typically recognized by others as nonverbal cues that mark a place as temporarily reserved—for example, jackets, bags, papers, or a drink.

Time:

Chronemics refers to the study of how time affects communication. Time can be classified into several different categories, including personal, physical, and cultural time (Andersen, 1999). Personal time refers to the ways in which individuals experience time. The way we experience time varies based on our mood, our interest level, and other factors. Think about how quickly time passes when you are interested in and therefore engaged in something. Physical time refers to the fixed cycles of days, years, and seasons. Physical time, especially seasons, can affect our mood and psychological states. Some people experience seasonal affective disorder that leads them to experience emotional distress and anxiety during the changes of seasons, primarily from warm and bright to dark and cold (summer to fall and winter). Cultural time refers to how a large group of people view time. Polychronic people do not view time as a linear progression that needs to be divided into small units and scheduled in advance. Polychronic people keep more flexible schedules and may engage in several activities at once. Monochronic people tend to schedule their time more rigidly and do one thing at a time. A polychronic or monochronic orientation to time influences our social realities and how we interact with others. Additionally, the way we use time depends in some ways on our status. For example, doctors can make their patients wait for extended periods of time. Executives and celebrities may run consistently behind schedule, making others wait for them. Promptness and the amount of time that is socially acceptable for lateness and waiting varies among individuals and contexts.

6.3.4: Personal and Environmental Presentation

Personal Presentation involves two components: our physical characteristics and the artifacts with which we adorn and surround ourselves with. Physical characteristics include body shape, height, weight, attractiveness, and other physical features of our bodies. We do not have as much control over how these nonverbal cues are encoded as we do with many other aspects of nonverbal communication. However, these characteristics play a large role in initial impression formation even though we know we “shouldn’t judge a book by its cover.” Although ideals of attractiveness vary among cultures and individuals, research consistently indicates that people who are deemed attractive based on physical characteristics have distinct advantages in many aspects of life.

While there are physical characteristics about ourselves that we cannot change, we do have control over our clothing choices, grooming behaviors, such as hair style, and the artifacts with which we adorn ourselves, such as clothes and accessories. Have you ever tried to consciously change your “look?” Changes in hairstyle and clothes can impact how you are perceived by others. In addition to artifacts such as clothes and hairstyles, other political, social, and cultural symbols send messages to others about who we are, such as piercings and tattoos. Jewelry can also send messages with varying degrees of direct meaning. A ring on the “ring finger” of a person’s left hand typically indicates that they are married or in an otherwise committed relationship. Expensive watches can serve as symbols that distinguish a CEO from an entry-level employee. People also adorn their clothes, body, or belongings with religious or cultural symbols, like a cross to indicate a person’s Christian faith or a rainbow flag to indicate that a person is gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, queer, or an ally to one or more of those groups.

In addition, we can use artifacts in the spaces we occupy, such as our home, office, or bedroom, to communicate about ourselves. The books that we display on our coffee table, the magazines a doctor keeps in his or her waiting room, or the placement of fresh flowers in a foyer all convey meaning to others. For example, imagine a bedroom that has the wall painted pink, a ruffle bedspread, and dolls displayed on the self. What do these items say about the person who occupies that room? What age would you think they are? Gender? What types of activities might you think the occupant likes by the various toys on display? In summary, whether we know it or not, our physical characteristics and the artifacts that surround us communicate much about us.

Artifacts: The artifacts that we use to decorate the spaces we occupy, such as a bedroom or office, can be used to communicate aspects of ourselves. Look at the artifacts in the above rooms. What do they communicate? Who lives in these spaces? Can you guess their age, gender identity, or socioeconomic status? What do you think they like?