In this section, we will cover techniques for understanding, expressing, and validating emotions, address contextual nuances surrounding emotional expression, and discuss ways in which our emotional expressions affect us and our relationships with others.

9.3.1: Effective Communication: Understanding, Expressing, and Validating Emotions

The notion of emotional intelligence emerged in the early 1990s and has received much attention in academic scholarship, business, education, and the popular press. Emotional intelligence “involves the ability to monitor one’s own and others’ feelings and emotions, to discriminate among them, and to use this information to guide one’s thinking and action” (Salovey, Woolery, & Mayer, 2001). As the definition of emotional intelligence states, we must then use the results of that cognitive process to guide our thoughts and actions. Just as we are likely to engage in emotion-sharing following an emotional event, we are also likely to be on the receiving end of that sharing. In order to better achieve your communication goals, it’s important to cultivate emotional intelligence. In the following subsections, we will provide strategies that will enable you to better understand and express your own emotions, as well as respond to the emotions of others

9.3.1.1: Understanding Emotions:

Before we can communicate our emotions to others, we first need to understand what we are feeling and why we are feeling that way. Here are some suggestions we can use to better understand our emotions:

Accept your feelings.

Before we can do anything else, we have to recognize and accept that we are going to have a wide range of feelings throughout our lives, and that there is nothing wrong with this. At their outset, feelings are not right or wrong; they just exist. When we feel something, we need not be angry or worried. Instead, we can think, “I am feeling this way, and that is acceptable.”

Recognize how the body is reacting to your feelings.

Feelings are driven by emotions, which are controlled by our brain. We need to take note of our physiological responses when we feel something as this will help us to better cultivate emotional intelligence. For example, we might sweat when we feel scared, our face might become warm when we are embarrassed, and our heart might race when we are angry. Keying into our bodily responses will help us recognize feelings as they come.[1]

Understand the basic emotions and learn the vocabulary of feelings.

There are eight basic human emotions: anger, fear, sadness, disgust, surprise, anticipation, trust, and joy. It is important that we develop an emotional vocabulary as it can be hard to understand and likewise express what we are feeling when we do not have the words to do so. Consider consulting an emotional vocabulary chart, such as the one provided in section 9.1.1, to get a sense of the wide variety of things we might be feeling. Attending to a wide range of possible labels for emotion actually lends nuance and richness to our understanding of the feelings we experience in a given situation (Lindquist, MacCormack, & Shablack, 2015). Using nuanced labels can also influence the way our emotions are perceived by others when we communicate them.

Ask yourself what you are feeling and why you are feeling a certain way.

Cognitive psychologists assert that our feelings are caused by our thoughts or beliefs. It’s not often we examine and bring attention to these beliefs. Doing so can help us better understand ourselves, and later generate more productive expressions of feeling. Here is a series of questions we can ask ourselves to get at the root of what we are feeling: What am I feeling? Why am I feeling this way? If the feeling is in response to another’s behavior(s)- how do I interpret that behavior and/or why does it bother me? For example, What? “I feel like I am going to cry. Why? Because I am mad at my boss. Why? Because he offended me. Why? Because he does not respect me.” We need to keep going with the series of “why” questions until we reach the bottom-line thoughts that underlie our feelings.[4]

Look for irrational or distorted thoughts.

Before expressing your emotions to others, and in the interest of better managing negative emotions, you might consider examining them for rationality. Doing so will help you put another rung in your ladder of emotional intelligence. Psychologist Albert Ellis identified a number of dysfunctional beliefs people hold that can lead to unnecessary suffering. Therapists all over the world help their patients identify and work with these beliefs to decrease distress. Among these are the following:

• “I must have the approval of others in order to feel good.”

• “Other people must behave the way I want them to.”

• “Life should be easy and free of suffering.”

Ellis posited that these thoughts are unrealistic and can lead to struggle, making us feel “stuck.” With awareness, though, the thoughts can–over time—be replaced with more rational beliefs that lead to healthy functioning. Ask yourself if your negative emotions fit with any of these irrational beliefs. If so, try to reframe the beliefs and repeat them to yourself frequently. Such a practice can help you process and own your emotions before you blame them on others, which could end up having an unintentional but negative (and sometimes even irreversible) effect on your relationships.

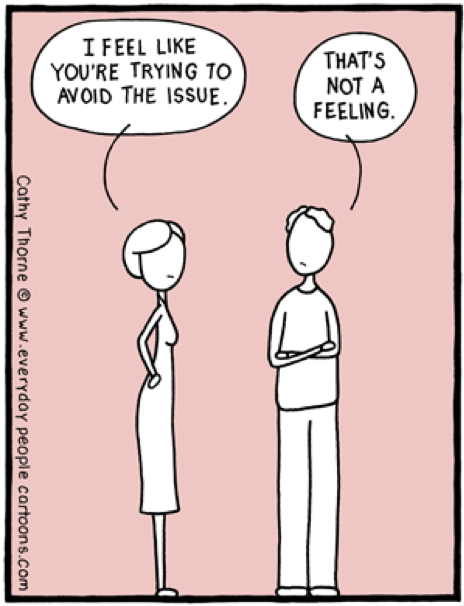

9.3.1.2: Expressing Emotions:

(Image: © Cathy Thorne/www.everydaypeoplecartoons.com; printed with permission for use in Interpersonal Communication Abridged Textbook (I.C.A.T.))

(Image: © Cathy Thorne/www.everydaypeoplecartoons.com; printed with permission for use in Interpersonal Communication Abridged Textbook (I.C.A.T.))

Understanding our emotions is a key component of emotional intelligence. However, it is also important to know how to effectively communicate those emotions with others. Effectively communicating our emotions has two parts: planning and expressing:

PLANNING

Identify what emotion(s) you want to communicate.

In some situations, we may be feeling several different emotions. Communicating a certain emotion could have either a positive or negative effect on the relationship, so it’s helpful to put some forethought into which ones you want to share. Take some time to consider what you type of conversation you want to have, and what you might hope to get out of it. For example, if your partner has recently been spending time with another person, we may feel resentment and anger, but we might also feel lonely and jealous. In this situation, you could choose to express any of the emotions you feel. However, each will probably take you in a different conversational direction. Disclosing anger might evoke defensiveness. Disclosing jealousy might be perceived as insecurity. Disclosing loneliness might open you up to vulnerability. Remember, referring to an emotional vocabulary chart might help you see a range of options you haven’t considered. Whatever you decide, be honest and know that conversations about emotions are often difficult but can also ultimately lead to greater relational outcomes.

Understand why you want to communicate the emotion(s).

Before we express our emotions, it’s a good idea to think about our communication goal. In other words, consider what you hope will happen as a result of your expression. Communication goals for expressing emotions may include venting, validation, affirmation, seeking support, etc. Or we may want a specific result from communicating that emotion. For example, if we feel hurt that a friend has been canceling plans with us and we may want to express this so that they don’t continue to do so. When seeking a specific result, we need to make sure to take the time to identify our preferred solution beforehand.

Think about where, when, and how you want to communicate your emotions.

This is an important part of how our expression will be interpreted by the other person, and could affect how they will react and respond. Consider the physical location of your expression Would it be best in a crowded bar? A park? A family dinner? Additionally, consider the timing of the disclosure. If we are feeling hurt that our romantic partner did not get us a birthday card, we may not want to express this immediately after they come home from a stressful day at work or right before an important meeting. We also need to consider the intensity of our own emotions in choosing appropriate timing. Confronting someone when feeling rage is probably not a good idea. Take time to calm down, breathe, and examine underlying thoughts before we express ourselves. The old saying “never go to bed angry” is out of touch with emotional intelligence. Sometimes sleeping off anger and letting time reduce the intensity of negative emotions is exactly what’s needed before we say something we might regret. Finally, we need to consider how we are going to express our emotions, as in whether it would be best as a face-to-face interaction or via a mediated communication platform, such as text messaging.

EXPRESSING

Take ownership of your feelings and use “I” language.

Using “I” language describes our own feelings and reactions, and acknowledges ownership of them. Compare this to “you” messages, which negatively evaluate the other person’s behavior and places the blame on them. Consider the difference between “I feel worried when I don’t hear right back from you” vs. “You always ignore me!” Beware of starting off with an “I” statement and switching over to a “you” message, as this negates the purpose of using “I” language in the first place. For example, “I feel like you are neglecting me” is not really an “I” message expressing your own emotional reaction. It is, instead, a negative evaluation of another’s behavior. “You” statements such as “you make me feel…” places the blame for your feelings on the other and is likely to cause defensiveness. Instead, rephrase statements to so that they convey your own feelings, as in “I feel lonely when we don’t hang out together” or “I feel anxious because decisions aren’t being made.” Often times, people do not mean to intentionally cause us to experience a negative emotion with their actions, so it is likely to be more effective if we take responsibility for how we are decoding and interpreting the actions of others.

Describe the emotion(s), what behavior caused the emotion(s), and the ‘why’ of the emotion(s):

- The emotion(s): Explicitly state the emotion(s) you are experiencing. The more specific we can be, the more likely the other will understand what we are feeling. Here, it is important to have a rich and nuanced emotional vocabulary to better understand and express these emotions to others as emotions can be mild, moderate, or intense. For example, consider the difference between the terms sad, melancholy, and despondent.

- The behavior: Just as it is important to be able to describe the specific emotion, it is likewise important to describe the specific behavior(s) that triggered that emotion. For example, if our roommate leaves dirty dishes on the kitchen counter we may feel annoyed. When describing the behavior, we should state only what we’ve observed, objectively and specifically, and not in an evaluative or accusatory manner. “Leaving dirty dishes in the kitchen” is an appropriate way to describe behavior, whereas “acting like a jerk” is an evaluation of that behavior, and not very conducive to productive interactions. Instead we could say “I feel annoyed when dirty dishes are left in the kitchen” versus “I feel annoyed when you act like a jerk.” The latter statement also contains a “you” statement versus an “I” statement.

- The why: Finally, it’s useful if we include a why in our “I” statement. Consider expressing a reason for why the behavior bothers us and leads to our particular emotional reaction? The why offers an explanation, interpretation, effect, or consequence of the behavior. One example might be “I feel annoyed when dirty dishes are left around the kitchen because it attracts cockroaches.” When describing the why, attempt to avoid “you” language. For example, saying “I feel sad when our plans are broken because you are neglecting me” still inserts that problematic “you,” which suggests blame and could lead to defensiveness. Instead, consider something like “I feel sad when our plans are broken because I want to spend more time together.”

“You” can easily creep into all three parts of an “I” message, and can be tricky to avoid at first, so you may want to mentally rehearse or even write down what you plan to say. Also, it is a good idea to repeat the statement back to yourself and think about how you might respond if someone said they exact same thing to you in a similar situation. If it would cause you to react negatively or defensively, revise your statement.

You might find that, in some situations, avoiding “you” may not be productive. At times, it might be useful to share the thoughts we attach to another person’s behavior. We can share our perspective by using a phrase such as “I took it to mean…” In this case, “you” might show up in your interpretation. However, you can reduce the potential for defensiveness by using language that reflects tentativeness and ownership. An example of this is “I’m confused about the dishes being left because it seems out of the norm for you, and I’m wondering if there’s some sort of message in this.” Another example might be “I get frustrated when the dishes are left on the counter because I remember talking about this before and I feel like I’m not being heard.” We will learn more about language and actions that contribute to and reduce defensiveness in the next chapter, Chapter 10: Communication Climate.

Respect the other’s emotional reaction and boundaries.

When we share our emotions with others, expect them to likewise have an emotional reaction to what we disclose. Sometimes people may behave defensively, or become angry, or upset. While “I” messages are useful in helping reduce these negative reactions, it doesn’t always eliminate them. The other person may also experience emotions such as concern, confusion, uncertainty, etc., and may not know how to convey what they are feeling or how to respond. While we may have had the time and forethought to analyze our emotions and plan out what to say, others may not have had this opportunity, and may need some additional time to process the message. In situations like this, it is best to be patient and work to keep your own emotional reactions in check. In addition, listening to and responding to the emotions of others can make some people extremely uncomfortable, so it’s necessary to respect their emotional boundaries.

9.3.1.3: Responding to Emotions

(Image: © Cathy Thorne/www.everydaypeoplecartoons.com; printed with permission for use in Interpersonal Communication Abridged Textbook (I.C.A.T.))

(Image: © Cathy Thorne/www.everydaypeoplecartoons.com; printed with permission for use in Interpersonal Communication Abridged Textbook (I.C.A.T.))

Another aspect of emotional intelligence is being able to appropriately respond to another’s emotions, in a way that offers support. One way we can offer emotional support when someone is experiencing a negative emotion (such sadness or anger) is to validate the emotion. Validating the emotions of others is useful because people experience relief when their emotions are recognized and understood by others. In the section below, we cover some guidelines for validating another person’s emotions:

DO

Engage in a people-oriented listening style.

In Chapter 7: Listening, we discussed the various listening styles: people-oriented, action-oriented, content-oriented, and time-oriented. A competent communicator changes style based on the context. As such, a people-oriented style that focuses on the speaker’s feelings—versus an action-oriented style that focuses on problem-solving—would likely be more helpful.

Normalize and validate their reaction.

We can normalize and validate a person’s feelings by indicating that it is okay and understandable to feel a particular way. For example, we can say something like, “I think most people in that situation would feel that way.” This shows that we think their reactions are reasonable and acknowledges the person’s right to be experiencing their emotions. Try some of the following:[7] “It’s okay to be squeamish about your flu shot. Nobody likes those.” “Of course you’re worried about asking your boss for a promotion. This sort of thing is scary for everyone.” “You’ve been dealing with a lot of stress lately- no wonder you don’t feel like going out today.”

Help them elaborate on their feelings.

After someone has expressed themselves, we can help them elaborate a bit about what they’re feeling and why. Paraphrases are useful in these situations. For example, we could say something like, “I imagine you’re feeling pretty hurt?” Doing so will show the person their feelings matter to us and that we are trying to understand them, as well as helping them further explore and understand their own emotions.[5]

Acknowledge personal history.

We can also help by acknowledging how the person’s history affects their emotions. This can be especially helpful if someone is worried they’re being irrational or unreasonable. While the person may be reacting in a way that seems over-the-top, we can help them understand they’re still allowed to feel their feelings. Try things like the following:[8] “Given how Pat treated you, I totally understand why you’d want to take a break from dating. That’s a lot to recover from.” “After that wreck you were in last week, I can see why you’d be hesitant to get back behind the wheel.”

Help the person re-frame/re-appraise the situation.

After validating someone’s emotions, it can be useful to help them re-frame or re-appraise the situation. When we do this, we provide information or observations that they may have missed, and we can offer another perspective or opinion. This encourages the speaker to try to see the situation in a different light. For example, if a friend is upset because their romantic partner has been spending less time with them and they are worried the other is losing interest in the relationship, we may offer an observation that their partner may just be busier than normal due to the promotion they just received.

AVOID

Avoid correcting someone’s thoughts or telling them how to feel.

Avoid the tendency to attempt to correct someone’s thoughts or feelings, especially when they are upset. If someone is being irrational, we may be inclined to try to talk them out of it. However, this can come off as negating the person’s feelings, as in the example, “That’s not something that’s worth getting angry about.” In addition, telling someone to “calm down” may imply they are being irrational, may invalidate their feelings, and/or may come off as you trying to tell them how to feel. Also, it’s okay to disagree with someone, and we can acknowledge emotions and feelings without directly agreeing with someone’s message or behavior. Instead, we can say something like, “I understand why that would make you angry.”

Avoid giving unsolicited advice.

Many times, when people tell us about a problem, they just want to be heard. Before you say something like “just ignore them” or “look on the bright side,” stop and listen more closely to what they are saying, and focus on sympathizing first. Listening is an important first step to helping others. After listening and acknowledging feelings we can ask if and/or how we can help. Sometimes it can be unclear whether or not someone wants our help or advice, so we can simply ask “Are you coming to me for advice, or would you just like to vent?”

Avoid blaming.

Blaming someone for their feelings, especially when they’re very upset, may come off as suggesting their feelings are not valid. You may want to avoid responses such as these:[11] “Whining about it isn’t going to make it any better. Man up and deal with it.” “You’re overreacting.” “So you decided to be mad at your best friend. How’s that working for you?” “Well, maybe he wouldn’t have treated you that way if you hadn’t been wearing such a short skirt.”

Avoid trying to “hoover” their feelings.

Hoovering means vacuuming up any unpleasant feelings and pretending they aren’t there.[12] Examples include:[13]”Oh, it’s not so bad.” “It’s not a big deal.” “Let’s stay positive.” “Just toughen up.” “Look on the bright side.”

Avoid trying to fix their feelings.

Sometimes we may try to help our loved ones stop hurting simply because we don’t want them to be upset. While well-intended, it usually doesn’t help them feel better long-term, and they may feel like it is their fault for still being unhappy after our efforts.[14] Instead, we can help by listening to the whole story and validating their feelings along the way. Then, we can ask how we can help or offer to brainstorm solutions. If helping them brainstorm, we should be conscious that we aren’t telling them what to do. We can also phrase things to show that we are speaking for ourselves or from our own experience. We can do this by beginning our statements with phrases like, “For me,” “In my experience,” and “Personally.” For example, “In my experience, it’s best to let go of someone who doesn’t want to be in my life. I’d rather spend time with the people who matter, like you.”

9.3.2: Contextual Communication: Emotional Rules and Norms are influenced by the Context

Whether you are expressing your emotions or trying to understand and respond to the emotions of others, emotions, like all communication, are contextual. Physical context can play a key role in what type of emotion is appropriate to display. For example, it may be okay to cry at a funeral, but not in the workplace. The relationship we have with another person can also shape what should or shouldn’t be expressed. You probably should not share private emotions with a complete stranger while waiting in line at the grocery store and instead reserve those for people with whom you are close. Individuals also have different personalities and life experiences, so they vary in terms of what emotions they are comfortable expressing and how they interpret the behaviors of others.

While all contexts are important, two in particular shape the expression of emotions in significant ways: culture and co-culture

9.3.2.1: Culture:

While our shared evolutionary past dictates some universal similarities in emotions, emotional triggers and norms for displaying emotions vary widely. Certain emotional scripts that we follow are culturally situated and affect our day to day interactions. Display rules are cultural norms that influence emotional expression. Display rules influence who can express emotions, which emotions can be expressed, where they can be expressed, and how intense the expressions can be. In individualistic cultures, where personal experience and self-determination are values built into cultural practices and communication, expressing emotions is viewed as a personal right. In collectivistic cultures, emotions are viewed as more interactional and less individual, which ties them into social context rather than into an individual right to free expression. An expression of emotion reflects on the family and cultural group rather than only on the individual. Therefore, emotional displays are more controlled, because maintaining group harmony and relationships is a primary cultural value, which is very different from the more individualistic notion of having the right to get something off your chest.

Cultural norms can also dictate which types of emotions can be expressed. In individualistic cultures, especially in the United States, there is a cultural expectation that people will exhibit positive emotions. People seek out happy situations and communicate positive emotions even when they do not necessarily feel positive emotions. Being positive implicitly communicates that you have achieved your personal goals, have a comfortable life, and have a healthy inner self (Mesquita & Albert, 2007). This cultural predisposition to express positive emotions is not universal. The people who live on the Pacific islands of Ifaluk do not encourage the expression of happiness, because they believe it will lead people to neglect their duties (Mesquita & Albert, 2007).

(Image: CCO)

(Image: CCO)9.3.2.2: Co-Culture:

While emotional display rules exist for larger cultural groups, they can also vary based on co-cultural factors, like gender identity. In the U.S. many norms have been socially constructed for emotional expression based on whether you present yourself as a man or woman. It is a common misconception that males do not (or should not) feel emotions and that females are ‘overly emotional.’ Biological sex has no influence on our ability to experience a particular emotion. Gender is socially constructed, so our emotional expressions are based on the gendered scripts and norms we are given to follow. “Boys don’t cry” is one obvious example. Girls are likewise encouraged to express positive emotions by constantly being told things such as “you should smile more” or “you would look prettier if you smiled.”

In addition, the way an emotional expression is perceived by others is influenced by our gender identity. For example, if a female is not overly emotionally expressive they may be perceived as cold, or if they express anger they may be labeled a ‘bitch.’ Conversely, men may be called weak if they cry or ‘pussy-whipped’ if they express too much love and devotion in a relationship. Emotions such as jealousy may be romanticized and interpreted as ‘caring’ or ‘protective’ when exhibited by men, but may be construed as ‘clingy’ or ‘insecure’ for women.

9.3.3: Reflective Communication: Emotions Can Affect Us, Others, and Our Relationships

Emotional competence entails thinking about the potential effects of particular emotional expressions. Specifically, what we choose to express (or not to) may affect our own emotional well-being, the perception others may have of us, and our relationships with others.

9.3.3.1: How Emotions Affect Us:

Expressing emotions can have important effects on our well-being, depending on how and with whom we share our emotions. Emotions convey information about our needs; negative emotions can signal that a need has not been met and positive emotions can signal that it has been meet. In some contexts, conveying this information can have a negative impact. For example, a person may choose to ignore or exploit our needs after we’ve disclosed an emotion.[30]

Researchers note that there are numerous important benefits to expressing emotions selectively. In the case of distress, expression can help us take control of our emotions and facilitate meaning-making to help better reappraise our situation. For instance, emotional expression through writing can help us better understand our feelings, and subsequently regulate our emotions or adjust our actions.[31] In addition, sharing our emotions with others can cause relief and inner satisfaction.

While expressing emotions has implications for how we feel, emotional expression can also influence how others see us, both positively and negatively. Individuals who inappropriately express emotions like anger or jealousy may be perceived as irrational. Individuals who express negative emotions, in particular, may also appear less likeable as a result.[33]

9.3.3.2: How Our Emotions Affect Others:

We should also be aware that our expressions of emotion are infectious due to emotional contagion, or the spreading of emotion from one person to another (Hargie, 2011). Think about a time when someone around you got the giggles and you couldn’t help but laugh along with them, even if you didn’t know what was funny. While those experiences can be uplifting, the other side of emotional contagion can be unpleasant. For example, if someone constantly interjects depressing comments into the happy dialogue, it can change the mood of the conversation. We’ve probably all worked with someone or had that family member who can’t seem to say anything positive, and this can cause frustration and annoyance.

9.3.3.3: How Emotions Affect Relationships:

Emotional expression has implications for our relationships as well. Our social bonds are enhanced through emotion sharing because the support we receive from our relational partners increases our sense of closeness and interdependence. When someone responds to our emotional expressions with empathy and validation, our relationship with that person can improve. Additionally, emotional expression to someone else can be viewed as a form of disclosure and sign of trust with that person, thus promoting intimacy. Greater expression of emotions or willingness to express negative emotions, such as anxiety or fear, promotes the formation of more relationships, greater intimacy in those relationships, and more support from others.[30][33] Conversely, lack of sharing, lack of empathy, and invalidation of emotions can cause relationship dissatisfaction and even deterioration. Sharing our emotions may also be a necessary part of effective problem-solving and conflict management, a topic that will be covered in Chapter 11: Interpersonal Conflict.