The History of New Mexico

Collapse

Expand

-

Chapter 10: Americanizing & Modernizing Ethnic Identities

- Americanizing & Modernizing Ethnic Identities

- "Apache Wars" & The Border

- Creating The Land of Enchantment

- Spanish-American Ethnic Identity

- References & Further Reading

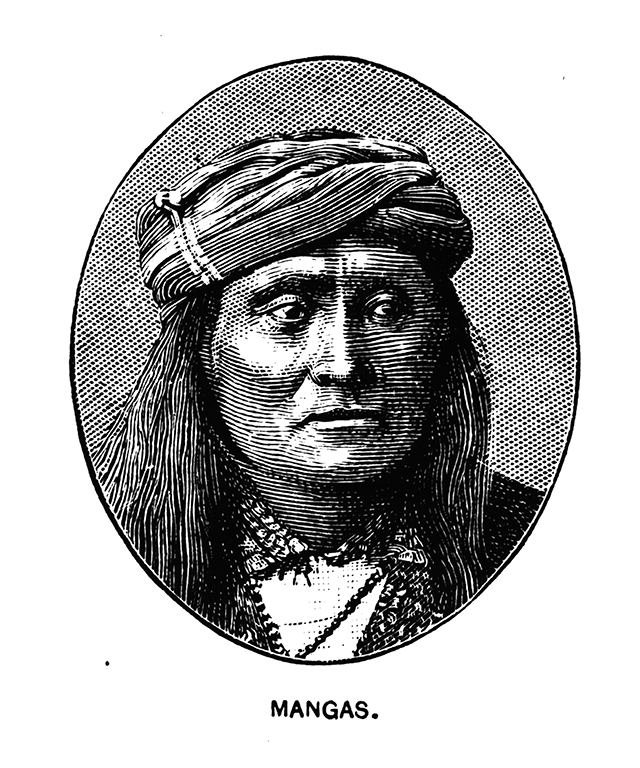

In the early morning hours of January 18, 1863, U.S. soldiers at Fort McLane executed Chiricahua headman Mangas Coloradas. Recognized as war chief of all four Chiricahua bands, Mangas Coloradas spent nearly two decades working to build peaceful ties with the U.S. military and American settlers in southern New Mexico. Yet his willingness to trust U.S. officials resulted in his brutal murder. Indeed, members of his band warned him not to attempt to negotiate with Brigadier General Joseph Rodman West on that winter day.

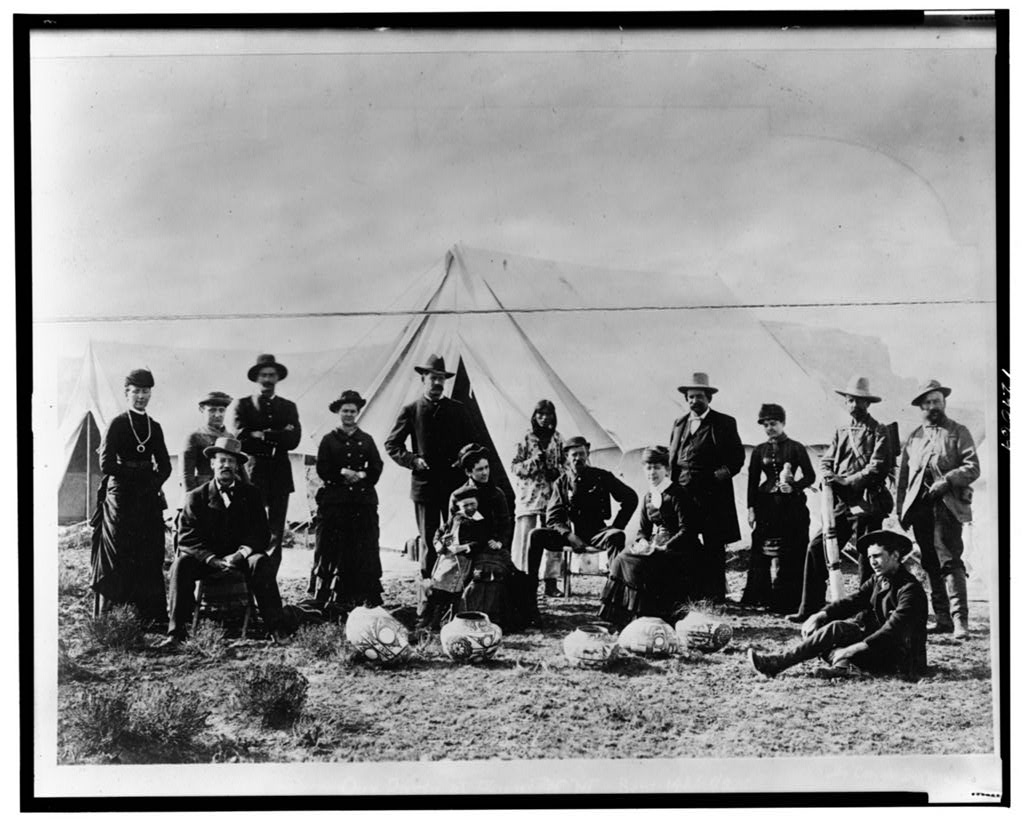

Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 133701

Earlier, in the fall of 1846, following the occupation of Santa Fe, General Stephen Watts Kearny led his forces southward en route to California with Kit Carson as guide. Along the way, his party passed through Chiricahua lands where they encountered Mangas Coloradas. Kearny and the Chiricahua headman quickly recognized that they had a common enemy in Mexico. Mangas Coloradas was fully engaged in the War of a Thousand Deserts, and he held a deep hatred of Mexican people due to wrongs that he believed they had committed against him and members of his band.

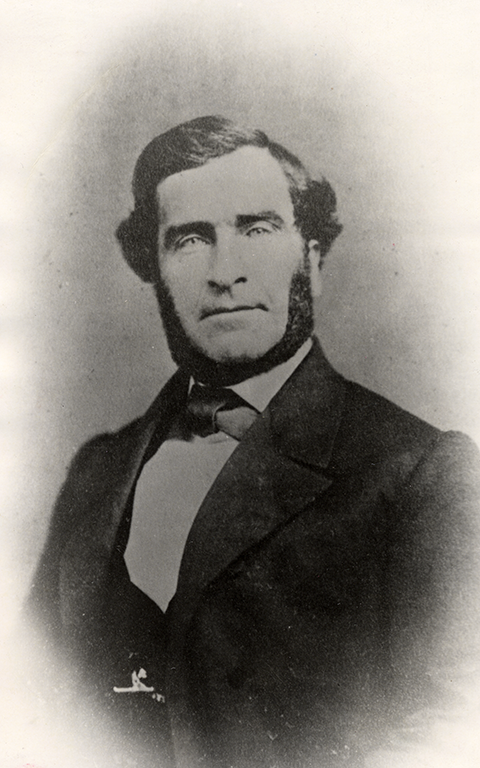

Despite common ground, forging alliances with U.S. military representatives was no easy task. Misunderstandings and broken promises characterized U.S.-indigenous relations during the period between the U.S.-Mexico War and the Civil War. Still, Mangas Coloradas made a favorable impression on most Americans who attempted to understand him. In 1851, during the boundary survey, John Russell Bartlett met Mangas Coloradas at the survey headquarters at Santa Rita. According to Bartlett, the Chiricahua headman possessed “strong common sense and discriminating judgment.”1

Courtesy of Center for Southwest Research, University Libraries, University of New Mexico (William A. Keleher Collection)

Additionally, Mangas Coloradas maintained a respectful relationship with Agent Michael Steck, appointed to the Chiricahua people in late 1854. At about that time, the Chiricahua leader decided that his advancing age made raiding expeditions into Mexico quite burdensome. Much to Steck’s surprise, he expressed his desire to settle into life on the reservation that the Indian Agency had proposed along the New Mexico-Arizona border.

Only two years earlier, Mangas Coloradas nearly torpedoed treaty negotiations with Colonel Edwin Vose Sumner over U.S. military attempts to enforce Article XI of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Upon hearing that his people would no longer be permitted to conduct raids into Sonora and Chihuahua, Mangas Coloradas walked away from the talks. Only Sumner’s tacit, off-the-record assurance that the raids could continue brought him back. Mangas Coloradas could not comprehend that a truce between the United States and Mexico could translate into a truce between his own people and Mexico. After all, no Apaches had ratified the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

Tensions between Chiricahuas and U.S. military figures compounded in the late 1850s and early 1860s as increasing numbers of Anglos migrated to the Apache homelands. Mangas Coloradas tolerated the creation of several Butterfield Overland Mail Company stations, and the influx of ranchers and farmers to the Mimbres and Gila Rivers near the center of both Bedonkohe and Chihenne (two of the Chiricahua bands) homelands. Even after he lost two of his sons in a skirmish with Sonoran troops south of the border in 1858, the headman resolved to maintain peace.

As the Civil War began in the East, new assaults on his people forced Mangas Coloradas’ hand, as he remembered it. Specifically, he was outraged when American miners from Pinos Altos attacked Chihenne Chief Elias’ temporary encampment as he awaited an audience with Agent Steck. In the skirmish, Elias and three others lost their lives. Then, in February 1861 Lieutenant George N. Bascom led troops against Cochise (Mangas Coloradas’ son-in-law) and his band in southeastern Arizona for a raid that had been committed, as it turned out, by a band of Pinal people. In what became known as the Bascom Affair, Cochise narrowly escaped with his life after an invitation to negotiate. Bascom captured six of his companions, and the conflict devolved into a hostage standoff in which both leaders killed all of their captives.

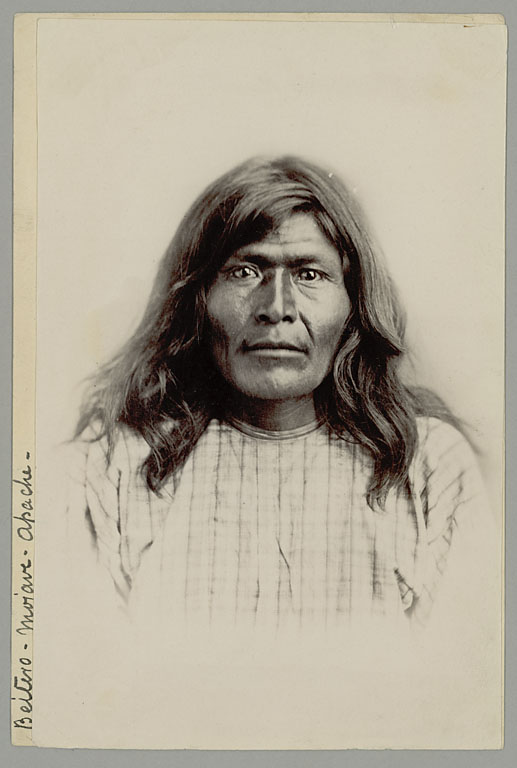

Courtesy of National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution

Increasing conflicts convinced Mangas Coloradas to join with Cochise in waging war against U.S. forces. Their efforts, combined with the abandonment of garrisons in southern New Mexico as soldiers were reassigned to the conflict in the East, restored Chiricahua control of the region for a short period of time. Chiricahuas of all bands freely traversed their traditional homelands once again, and Victorio (another Chihenne headman) and Juh (a Nednhi chief) joined with Mangas Coloradas and Cochise in an effort to ensure their continued hold on the area.

In the summer of 1862, however, General James H. Carleton led the California Column through Chiricahua territory en route to relieve Colonel Edward R. S. Canby as commander of the New Mexico department. As his own contemporary communications and his later actions with the Bosque Redondo illustrate, Carleton held no respect for indigenous peoples. The California Column engaged the Chiricahuas, and in late-July 1862 Mangas Coloradas lay gravely wounded.

Mangas Coloradas believed that he would be negotiating with leaders like Kearny or Sumner when he approached Pinos Altos to make peace on the afternoon of January 17, 1863. Instead, General West was of a similar mind as Carleton. After imprisoning Mangas Coloradas at Fort McLane, West privately informed his men that he did not want the Chiricahua headman alive the next morning. The guards tortured Mangas Coloradas by prodding him with their bayonets after heating them in the fire. After enduring an hour of this treatment, he told the sentinels in Spanish that “he was not a child to be played with.”2 As soon as he uttered those words, two of the guards leveled their rifles and shot him. Another rushed over and fired an additional shot through the back of his head.

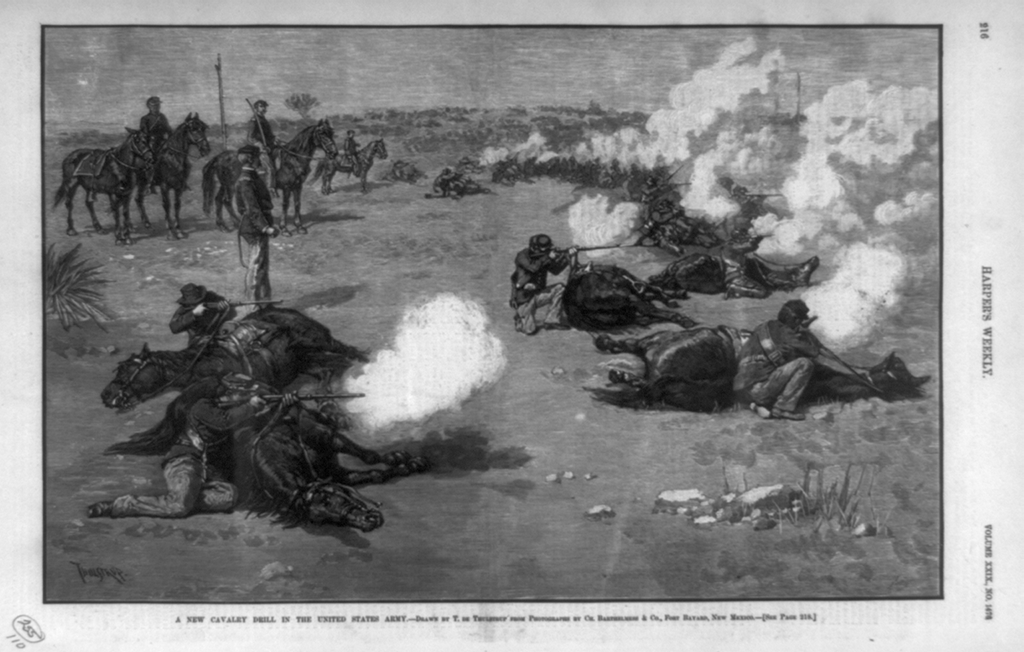

Courtesy of Library of Congress

Contrary to the intentions of West and Carleton, the brutal murder and subsequent decapitation of the respected leader initiated a new cycle of hatred and retributive violence. Rather than breaking the Chiricahuas’ will, Mangas Coloradas’ execution heightened their resolve to resist American encroachments, especially because soldiers had defaced and decapitated the corpse. According to Apache belief, a person’s body continues into the afterlife in the same condition that it left mortality. Victorio, Cochise, Juh, and Geronimo (a young Bedonkohe leader who rose to prominence in the 1860s) led the Chiricahuas for the next three decades in brokering war and peace with Americans and Mexicans in the border region. On that fateful night in January 1863, an opportunity for negotiation was squandered at the cost of near constant warfare until Geronimo’s surrender in the Sierra Madres of Chihuahua in 1886.

The story of Mangas Coloradas’ execution is a crucial part of New Mexico’s histories, not only because it provides another indictment of the attitudes of military leaders like Carleton and West, but also because his life and death inspired resistance that later American observers referred to as the “Apache Wars.” Geronimo’s capitulation signaled an end to warfare in the West, and promoters and entrepreneurs almost immediately began to broadcast New Mexico as the place where Eastern Americans could find a new beginning as farmers. Railroads and the territorial Bureau of Immigration furthered New Mexico’s tourist image.

As a result, the same place and peoples defined by opponents of statehood as “backward” and “unprepared” were heralded by boosters as “the most American” of all others in the Union.3 Because those diametrically opposed claims were based on different interpretations of the same cultures and peoples, boosterism in New Mexico always had clear limits. Within this context of paradoxical interpretations of New Mexico and its peoples, nuevomexicanos recast themselves as “Spanish Americans” in an effort to appear eligible for statehood and gain full inclusion in the union as U.S. citizens.

Courtesy of Library of Congress