The History of New Mexico

Collapse

Expand

-

Chapter 3: Patterns of Spanish Exploration & Conquest

- Patterns of Spanish Exploration & Conquest

- La Reconquista: "Kindergarten of Colonization"

- An Age of Exploration

- The Conquest of Mexico

- Fray Marcos de Niza's Journey

- Searching for "Nuevo México"

- Conquest Redefined

- References & Further Reading

Once each Iberian kingdom completed its leg of the reconquest, its resources were freed up for other pursuits. After the capture of Algarve, Portuguese kings focused their attention on solidifying royal administration during the remaining years of the thirteenth century. Such efforts were intermittently disrupted by Castilian kings’ and adelantados’ efforts to subjugate Portugal to Castile. Civil wars between those loyal to the two Christian kings took a toll on Iberia’s economies and its political advancement. By the early 1400s, Portugal had been able to hold off Castilian advances for a long period of time, a development that allowed its nobles to focus their attention on the seas.

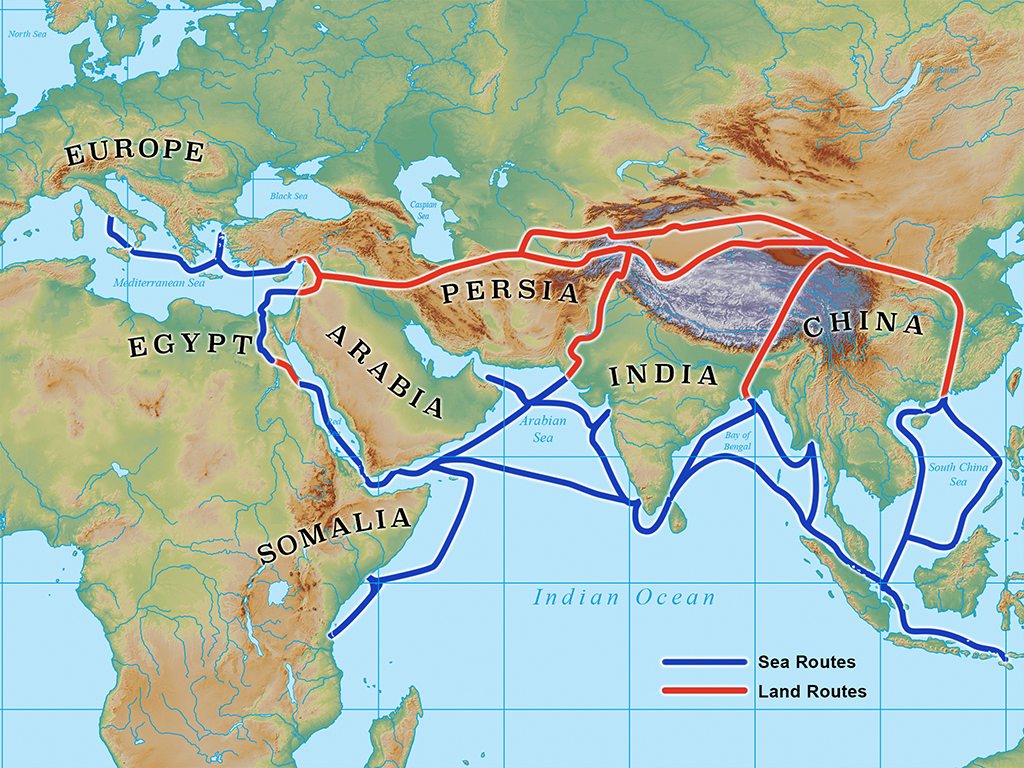

Beyond a simple curiosity about the unknown world that lay beyond the oceans, the possibility of commercial expansion and economic gain motivated Iberian monarchs to support maritime exploration. By the 1400s people throughout Europe had long been accustomed to the use of spices and other luxury items from Asia. Not long after the Portuguese completed their reconquest and Castilian forces captured Andalusia, Marco Polo embarked on his famous journeys to the Far East. Although not the first European to make contact with China or the fearsome leaders of the nomadic Mongolian Empire, Polo was the first to leave a detailed account of his journeys. His tales, despite their embellishments, introduced Europeans to peoples and cultural practices that they came to consider as exotic and luxurious. Silks, spices, diamonds, rare dyes, and pearls were among the trade goods that most excited those who read his narrative.

During the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, spices from the Moluccas, known to Europeans as the Spice Islands, became the hottest trade commodity in most Western European domains. Spices were a luxury item coveted by nobles and wealthy professionals. They were used to flavor and preserve meat and other foods, as perfume, and for medicinal purposes. Some believed that certain spices would ward off the Bubonic Plague if held over the nose and mouth while in public. By the 800s, spices such as cinnamon, ginger, cassia, and turmeric were traded in Islamic realms in the Middle East. During the Italian Renaissance, Mediterranean merchants made a fortune by forging a link between Islamic traders and the growing markets for spices in Europe.

By the early 1400s, Portuguese leaders sought a means to capitalize on the trade in spices as well. Their efforts to modernize maritime technology and shipbuilding opened the way for Portuguese sailors to seek out a new sea route to China, India, and Indonesia. Prince Henrique, known in English-language history texts as Henry the Navigator, is largely credited with heading up Portuguese exploration programs. He was the son of João I, the founder of the Aviz royal dynasty. As the third child of the king, Henrique did not stand to inherit the throne, but he did possess great political sway and resources to support his interests. In the 1420s, he invited cartographers, shipbuilders, and other maritime experts to his villa (sanctioned township) at Sagres in southern Portugal. Although there has been some historical debate over whether or not the group at Sagres constituted an actual school, new technologies emerged due to Henrique’s efforts. Through his patronage of maritime research, new means of mapping and navigating open waters paved the way for longer-range sea exploration.

New ships, called caravels, were developed to allow for increased maneuverability closer to shorelines. Additionally, the new ships were sleek and agile, allowing them to sail much nearer to the coast than conventional vessels. Yet the ships maintained a large cargo capacity. More precise maps allowed sailors to document their travels more accurately, thus furthering geographic knowledge and continued exploration. Henrique pushed the Portuguese sailors to find a way to travel around Cape Bojador on the west-African coastline. The cape was a region of fierce winds that had long prevented journeys along the southern coasts of Africa. After Henrique’s death in 1460, Portuguese sailors continued to press forward. By the 1480s, Portuguese sailors had achieved his goal for them and much more. At mid-decade they had navigated around the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of Africa and proceeded eastward into the Indian Ocean.

As they traveled around Africa and to India, Portuguese captains made contact with people that lived along the coasts. In the process, they established trade relationships and permission to create a series of outposts. Theirs was a commercial empire constructed on navigational technology and diplomacy. Rather than seeking territorial conquest as representatives of Castile and Aragon would later do, Portuguese sailors established small footholds in faraway lands that allowed them to create and maintain trading dominance for the better part of the sixteenth century.

Christopher Columbus initiated his efforts at exploration with much the same model in mind. He certainly targeted the same economic activity; he wanted to locate yet another route to the Spice Islands by sailing west. If he was successful, his patrons would cut away at Portugal’s dominance of European commerce. After years of planning and pitching his desired excursion, Fernando and Isabel agreed to finance Columbus in the spring of 1492. That January had marked the end of their Reconquista when the final Muslim stronghold of Granada fell following ten years of sustained conflict.

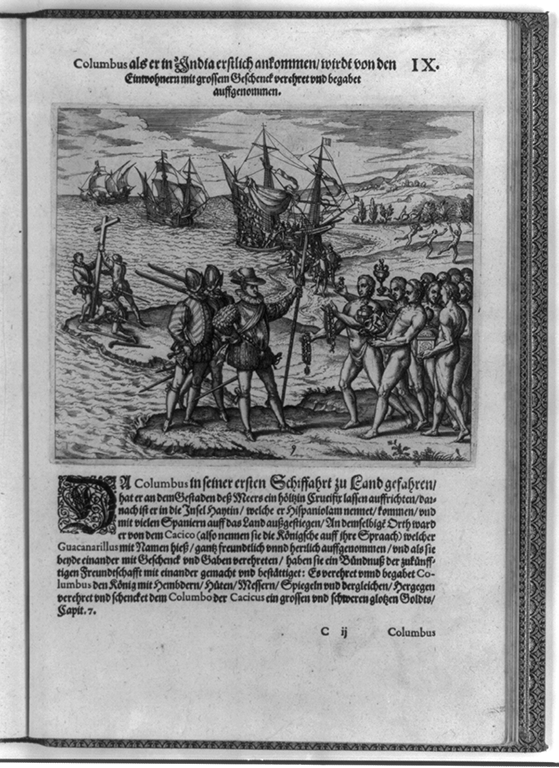

Courtesy of Library of Congress

Shortly thereafter, the Catholic Kings (Fernando and Isabel received that nickname for their stringent dedication to the defense and expansion of Catholicism) entered into a contract with the Genoese navigator. Both had high expectations for his journey across the “Ocean Sea,” the name then used for the Atlantic Ocean. Isabel named Columbus “admiral, viceroy, and governor” over any lands that he might encounter and subdue. His contract also granted him “one-tenth of all merchandise, whether pearls, gems, gold, silver, spices, or goods of any kind, that may be acquired by purchase, barter or any other means, within the boundaries of the Admiralty jurisdiction.”5 In August, Columbus set sail with three ships and ninety sailors.

Despite the persistence of the claim that most people in Columbus’ day believed the world to be flat, such was not the case. That idea was actually the creation of nineteenth-century commentators as they looked back on late fifteenth-century explorers. Instead, people living across the globe had conceptualized the world as a sphere since ancient times. The debate during Columbus’ lifetime was over the size of the earth. Columbus used the best knowledge and methods then available to reach the conclusion that the world was about two-thirds its actual circumference. He was not aware of the American continents, and his calculations led him to believe that sailing to the west would allow him to reach China and other points in India and Indonesia.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

In early October, Columbus’ contingent made landfall on the island of Guanahaní in the Bahamas, which he promptly renamed San Salvador. He then proceeded to explore the region, passing along the northern coast of Cuba and then eastward to the island of Hispaniola. In the spring of 1493 he made his triumphant return to the royal court of Queen Isabel, where he reported that he had “found very many islands, inhabited by numberless people.” He brought with him native Taino people that his party had captured on Hispaniola. His various reports on the indigenous peoples—whom he erroneously called Indians—and their lands were positive to the point of exaggeration. He noted that both Cuba and Hispaniola were veritable tropical paradises, complete with fertile soil, excellent harbors, abundant vegetation, freshwater, delicious fruit, and colorful birds and animal life. Native peoples in those places were “exceedingly straightforward and trustworthy and most liberal with all that they have.” His accounts also painted the natives as “readily submissive,” not given to idolatry, and willing traders of gold, silver, and other precious objects.6

This type of overblown reporting fit the general pattern of exploration and conquest that had been followed by agents of Iberian kings since the early years of reconquest. Eager to secure their claim to wealth, authority, and noble titles, adelantados wrote probanzas de mérito (proof of merit). In order to convince kings or queens that their conquests had merit, and also to show their competence as leaders, conquistadores made their case in the strongest way possible. Their appeals to the monarch were made to give their own acts legitimacy and justification. If their actions were legitimate and just, by extension they stood to receive the wealth and authority stipulated in the terms of their individual contracts. As one historian has explained, “the very nature and purpose of probanzas obliged those who wrote them to promote their own deeds and downplay or ignore those of others.”7

Unfortunately for Christopher Columbus, his efforts did little to guarantee his own wealth or standing. Isabel dispatched seventeen ships carrying almost 1,500 people, mostly men, to the Caribbean to establish a permanent colony on Hispaniola in late 1493. Columbus proved inept as an administrator, however, and the queen revoked her earlier contract with the sailor in 1500. Another governor took control of the colonial government at Santo Domingo, the first Castilian settlement in the Americas. His first official action was to place Columbus under arrest. Although Columbus led three other sailing expeditions in the Caribbean and along the coast of Yucatán, glory eluded him during his own lifetime. Even the name of the “new world” escaped his mark. Instead of being named after Columbus, the continents of the Western Hemisphere were named after Amerigo Vespucci, Columbus’ friend and associate who wrote prolifically of his various exploratory journeys.

Columbus’ attempts to undercut Portuguese commercial dominance and create a name for himself set the stage for extended contact between Europeans and indigenous Americans. Despite the rosy accounts penned by early explorers, First Peoples were not naturally submissive or pliant. Many forcefully resisted Spanish attempts to subjugate them. Others retreated to remote areas beyond the reach of the Europeans. Still others created alliances with the conquerors. Despite more recent characterizations of such people as traitorous, most had complex reasons for supporting the newcomers. To refer to such people as traitors is to misunderstand the nature of relations between indigenous groups. They clearly did not consider themselves to be part of a single society, although the term “Indians” cast them as such. Alliances between indigenous groups and Spanish entradas allowed a seemingly small group of colonizers to take control of large swaths of land that were inhabited by advanced societies.