The History of New Mexico

Collapse

Expand

-

Chapter 10: Americanizing & Modernizing Ethnic Identities

- Americanizing & Modernizing Ethnic Identities

- "Apache Wars" & The Border

- Creating The Land of Enchantment

- Spanish-American Ethnic Identity

- References & Further Reading

Competing claims for land and resources in the New Mexico-Chihuahua borderlands inspired conflict in the 1870s and 1880s. The Chihenne band of the Chiricahua Apache people had dominated the region since the late 1300s or the early 1500s, depending on differing estimates. As we saw in Chapter 2, although scholars do not agree on the time of Athabaskans’ arrival (including all Navajo and Apache bands and clan groups), the Chihenne people consider the region bounded by the Mimbres, Black, Sierra Negretta, San Mateo, and Florida mountain ranges their sacred homeland. Ussen, the Chiricahua creator, placed them within the territory and entrusted them with its care.

As anthropologist Edward Spicer has pointed out, the Chihenne homeland became a “region of borders” by the late 1700s as numerous indigenous peoples worked to maintain their place in what had then been redefined as the far northern frontier of New Spain.4 Misunderstandings about Apache social and political organization plagued Spanish encounters with the various bands in and around the New Mexico colony. The Chihenne, also called the Mimbreño, Mimbres, Ojo Caliente, or Warm Springs people, organized themselves into local groups which ranged in size from thirty-five to two-hundred members. The Spaniards referred to their home sites, at times semi-permanent, at others more temporary, as rancherías. By the time the United States laid claim to their homelands, Apache peoples had endured various attacks on their place in the region. Even after Mangas Coloradas’ execution, however, few of them realized that the American challenge would prove to be the most devastating of all.

Tensions between the Chihenne people and American miners, farmers, and soldiers persisted throughout the 1860s and into the 1870s. Victorio led his people far from their homeland at Ojo Caliente, now called Warm Springs in recognition of U.S. control over New Mexico. They ranged between the Blue, Florida, Black, and Mogollon Mountains, and Chihenne warriors led regular raids against settlements in the Chihuahua sierra. In the early 1870s Victorio grew weary of so much wandering and negotiated the return of his people to the Warm Springs Agency under agent Charles Drew. According to historian Kathleen P. Chamberlain, Drew “was one of the best agents the Apaches ever had, second only to Michael Steck.”5 Despite the ongoing problem of Congress’ failure to ratify agreements made between Indian Agents and Native peoples, Victorio settled his band once again in a limited version of their ancestral homeland with an agent that served as a strong advocate.

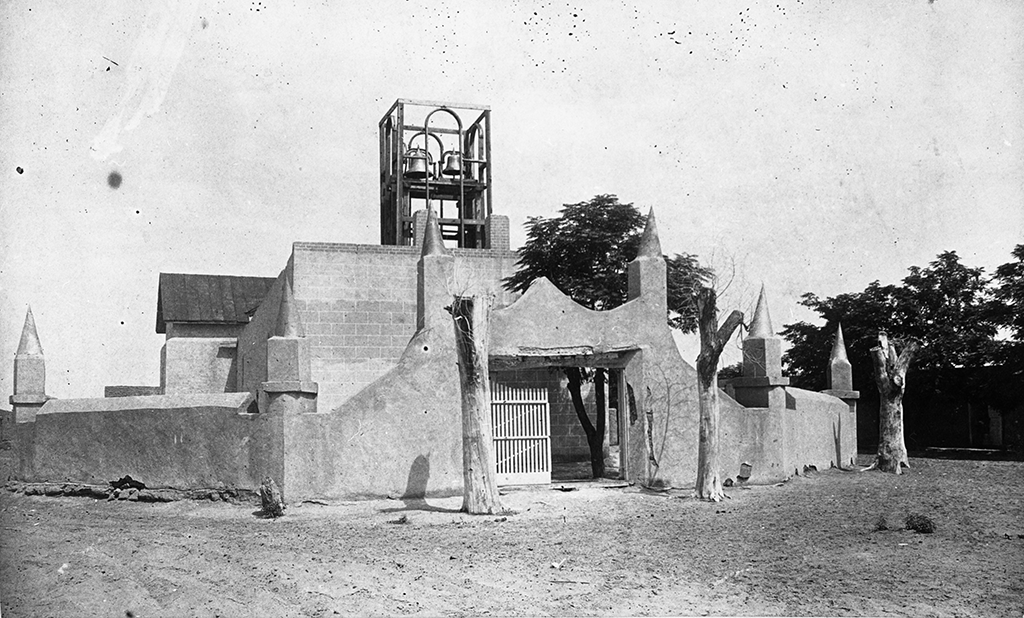

At about the same time, near the international border, mesilleros faced a new type of conflict in their community. Having settled into their lives as American citizens along the border, they actively participated in the religious and political culture of Doña Ana County. In August of 1871 campaign activities for an election between Democrat José Manuel Gallegos and Republican José Francisco Chaves inspired a bloody riot that left eight people dead and scores of others wounded.

In Mesilla, electoral politics merged religious and ethnic sympathies. Father José Jesús Baca, the senior Catholic priest in town, publicly pronounced that Gallegos’ affiliation with the Democratic Party and his sympathetic stance toward the U.S. government presented a threat to Mexican Catholics. Baca had previously requested to retain his affiliation with the Diocese of Durango, despite the transfer of other New Mexican parishes to the Diocese of Santa Fe. In doing so, Baca manifested his continued devotion to the Mexican nation, and his ideas on the significance of the 1871 election brought mesilleros’ religious and political loyalties into sharp relief.

In the campaign for territorial delegate to U.S. Congress, both Gallegos and Chaves levied charges that the other had committed electoral fraud. On August 27, 1871, when their respective supporters held rallies on the Mesilla plaza, such accusations only served to fuel tensions. As was common in the culture of nineteenth-century American politics, free whisky and live bands contributed to the charged atmosphere. Each party marched around the town square, chanting slogans that favored their candidate and disparaged the competitor. Violence erupted as the two groups came face to face in front of San Albino’s church. As reported in the New York Times, “the Plaza has been literally drenched with human blood.”6 Troops from Fort Selden arrived shortly after the carnage had transpired and attempted to quell the disorder.

Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 122144

Once the dust had settled and Gallegos claimed victory in the election, a group of Republican mesilleros decided to abandon their homes in favor of a new start in northwestern Chihuahua. Although historians differ in terms of the reasons behind the relocation, the international border provided a barrier of refuge.7 Ninety-six families followed Ignacio Orrantía, U.S. deputy marshal for Doña Ana County, and Fabián Gonzales, Doña Ana County Sheriff, to Chihuahua before the Mexican government had approved their petition for a land grant. In the process of seeking out new opportunities, this group of Mesilleros reasserted their Mexican citizenship status and sought to capitalize on the drive for repatriation that was still current south of the border.

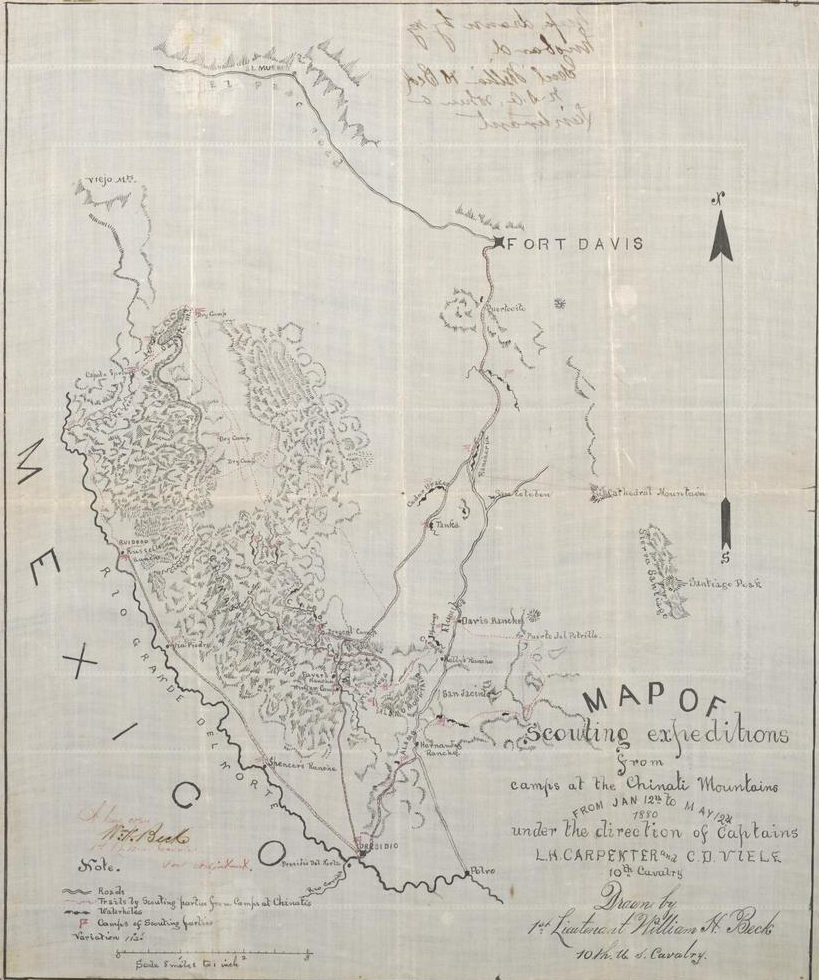

Courtesy of Special Collections of The University of Texas at Arlington Library

The following year, the migrants received official sanction for their new town of La Ascensión, Chihuahua. Their efforts to reinvent their community and alter their national status collided with Chihenne attempts to resist dependency on the U.S. government in the setting of the Warm Springs Agency. Despite their desire to remain in their homeland, and despite the best efforts of Agent Drew, Victorio and many of his warriors conducted raids into Chihuahua as a means of maintaining a sense of social and economic independence. They refused to submit passively to a system that required them to subsist on rations that were not always forthcoming.

As had been the case in the Mexican repatriation initiative of the 1850s, officials in Chihuahua hoped that the residents of La Ascensión would solidify their claims to lands adjacent to the international border. Chihuahua Governor Luís Terrazas supported the ascensionenses’ (as residents of La Ascensión came to be known) petitions for legal title to the lands they had settled near the Ojo de Federico (Federico Spring) for precisely that reason. Just over two decades after the ratification of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Mexican policy still held that settlement of the border region was the key to the conquest of the Apaches.

Whatever their feeling about a national policy that cast them as Apache fighters, or “part-time specialists in violence,”8 ascensionenses could not ignore that their new settlement was to be constructed within territory claimed by the Chihenne and Nednhi bands. Indeed, the first exploring party from Mesilla was disbanded in late 1871 due to skirmishes with Apache bands along the Casas Grandes River.

Asensionenses relied on legal surveys to stake their claims on the region. Of course, Chihenne and Nednhi people neither recognized nor accepted the conventions of modern law and boundary demarcation. During the first decade of town construction, conflicts with adjacent landowners and Chiricahuas impeded attempts to construct homesteads and canals. On two separate occasions in 1872, Apache people prevented settlers from building structures and digging canals.

In 1873 three young boys from La Ascensión were surprised, but unharmed, by a group of Chiricahuas who scattered the sheep they attended. Reportedly, the sheep were later sold on the San Carlos Reservation in Arizona. In 1878, as Victorio led his band in what proved to be their final campaign to preserve their autonomy against U.S. and Mexican military campaigns, a small group of Victorio’s men assaulted a group of asensionenses led by Juan Zuloaga as they transported goods to Corralitos. After a short scuffle, the Chiricahuas made off with the merchandise and several asensionenses lay wounded. In this instance and several others, militias were hastily organized at La Ascensión to pursue the Apaches. Most of the time, militia members failed to engage the Chiricahuas.

Although repatriation to northwestern Chihuahua and U.S. reservation policy placed great stress on Chiricahua peoples, for a time they were able to use the border to their advantage. For them, the border became a barrier to military action because U.S. and Mexican forces were prohibited from crossing into the other nation’s territory in pursuit of Apaches until 1882. Even then, their military activities were greatly limited when in the neighboring nation.

By the late 1870s, however, the border presented less of a refuge and Chiricahua dominance of their traditional homelands began to wane. As headmen like Victorio and Juh came to recognize, their methods of dominance were eclipsed by modern means of claiming lands imposed by both Mexico and the United States. Despite their longstanding supremacy in their traditional homelands, “the Apaches did not follow up their military domination with the creation of a formal boundary survey. Instead of maps and surveys, place names and patterns of movement demarcated the landscape of Apache authority.”9 As more and more Chiricahua bands relocated to reservations in Arizona and New Mexico, they continued the practice of raiding northern Mexican settlements in order to supplement their rations and maintain a semblance of independence.

Despite Victorio’s willingness in 1876 to promote peace by accepting reservation life at the Warm Springs Agency, a lack of consistent policy once again disrupted his best efforts. Indeed, Victorio’s own actions seemed contradictory as he attempted to help his band adjust to their new reality through both violence and negotiation. Although Agent Drew provided consistent support for the Chihennes’ continued claim to their Warm Springs homeland, his successors, John P. Clum and John Shaw, supported a policy of concentration. Beginning in 1876 they initiated a plan to round up Chiricahuas of all four bands and force them to live together at the San Carlos Reservation in southeastern Arizona.

Military might was a necessary component of reservation policy. No Apache band would have left their homeland if not for the use of force. Victorio was hostile to the idea that his people abandon the lands that Ussen had ordained for them, but, like Mangas Coloradas before him, his desire to maintain peace won out. In the summer of 1877, he led his people to a site near Camp Goodwin on the designated San Carlos Reservation, a place that one U.S. officer had referred to as “Hell’s forty acres.”10 The arrival of most of the Apache bands at San Carlos signaled the emergence of the form of modernization that U.S. politicians and military leaders had envisioned. Now vast expanses of Chiricahua homelands were made available for homesteaders and capitalist development, at the expense of Apache peoples.

At San Carlos, Victorio’s people endured sparse water, lack of vegetation, extreme temperatures, and hostilities with other bands. By September malaria had afflicted both young and old, and Victorio concluded that American officials consigned his people to the reservation “so that we will die.”11 On September 2, 1877, Victorio and the medicine man Loco stole horses from White Mountain Apaches also interned at San Carlos and made their escape with as many of their people as could travel. Despite their desire to return to Warm Springs, where they had cached weapons and supplies, they remained on the move in eastern New Mexico and northern Chihuahua in order to evade capture.

African Americans comprised a large portion of the troops in pursuit of the Chiricahuas. In southern New Mexico (and throughout the American West), African American men made up as much as half of the military force. African American soldiers serving in the U.S. army following the Civil War were widely known as “Buffalo Soldiers.” In 1866, Congress passed legislation that reorganized the army. In the process, they designated two regiments—the 9th and 10th—and four infantry units—the 38th through 41st—for black soldiers. Three years later, Congress formed the 24th Regiment from the former 38th and 41st and organized a new 25th from the 39th and 40th.

In the years between 1866 and 1900, nearly 3,600 black soldiers served in the New Mexico Territory. Accordingly, they saw action in most of the engagements with Chiricahua peoples. Despite their status as U.S. soldiers, the civilian population consistently opposed the presence of African American military men in both word and deed. Newspaper editors across the territory published derogatory statements against the 9th Cavalry, a black unit which was stationed at Fort Bayard to force Victorio’s band back to reservation life. In one inflammatory rant, the editor of the Thirty-Four (Las Cruces, New Mexico) concluded: “Let the Ninth be dismounted or disbanded . . . [so that its members] might contribute to the nation’s wealth as pickers of cotton and hoers of corn, or to its amusement as a travelling minstrel troupe. As soldiers on the western frontier they are worse than useless—they are a fraud and a nuisance.”12

Even as they fought to further the U.S. military agenda of Americanizing New Mexico Territory through campaigns against Chiricahuas, African American soldiers faced constant discrimination. The prejudice of white settlers remained strong despite black soldiers’ acts of heroism. In 1877 a detachment of the 9th Cavalry engaged Victorio’s band in the Florida Mountains. One officer, six cavalrymen, and two Navajo scouts had been dispatched to intercept the group of about fifty Apaches. As they attempted to negotiate with the Chiricahuas, the group was surrounded and attacked.

Courtesy of Pat Bennett

Among the soldiers was Corporal Clinton Greaves.13 By one account, Greaves “fought like a cornered lion.” Through his tenacious combat efforts in which five Chihenne warriors lost their lives, Greaves led his companions to safety. He was recognized for his heroic actions with a Congressional Medal of Honor, as were eight other African American members of the 9th Cavalry for their efforts against Apaches between 1877 and 1881.

It seemed, however, that the dedicated service of the Buffalo Soldiers was never enough to prove their valor to Anglo American residents of southern New Mexico. In 1880 when the 9th Cavalry unexpectedly came upon a large body of Apaches that had killed two servicemen, a private was dispatched to bring reinforcements. The African American soldier rode bareback all day and night because a white rancher had refused to lend him a saddle to help him perform his task. Although the rancher may have also refused aid had the soldier been white, settlers typically lent their support to white soldiers that worked to protect their lives and property. As one historian remarked, “the open and latent racism of the late nineteenth century had curious ways of expressing itself.”14

Pressure from the 9th Cavalry and the difficulties of supporting his band in lands that were not their own convinced Victorio to enter into negotiations with U.S. military officials at Fort Wingate in late 1877. The Chihenne headman made a deal that allowed his people to return to Warm Springs, but the arrangement did not last. After only a few months back in their homeland, officials in the Indian Department in Washington, D.C., ordered that all Apaches be sent back to San Carlos. [glossary_exclude]Geronimo[/glossary_exclude] and Pionsenay continued raids into Chihuahua and Sonora, convincing those in charge of the bureau that no Apaches could remain outside of the forbidding Arizona reservation.

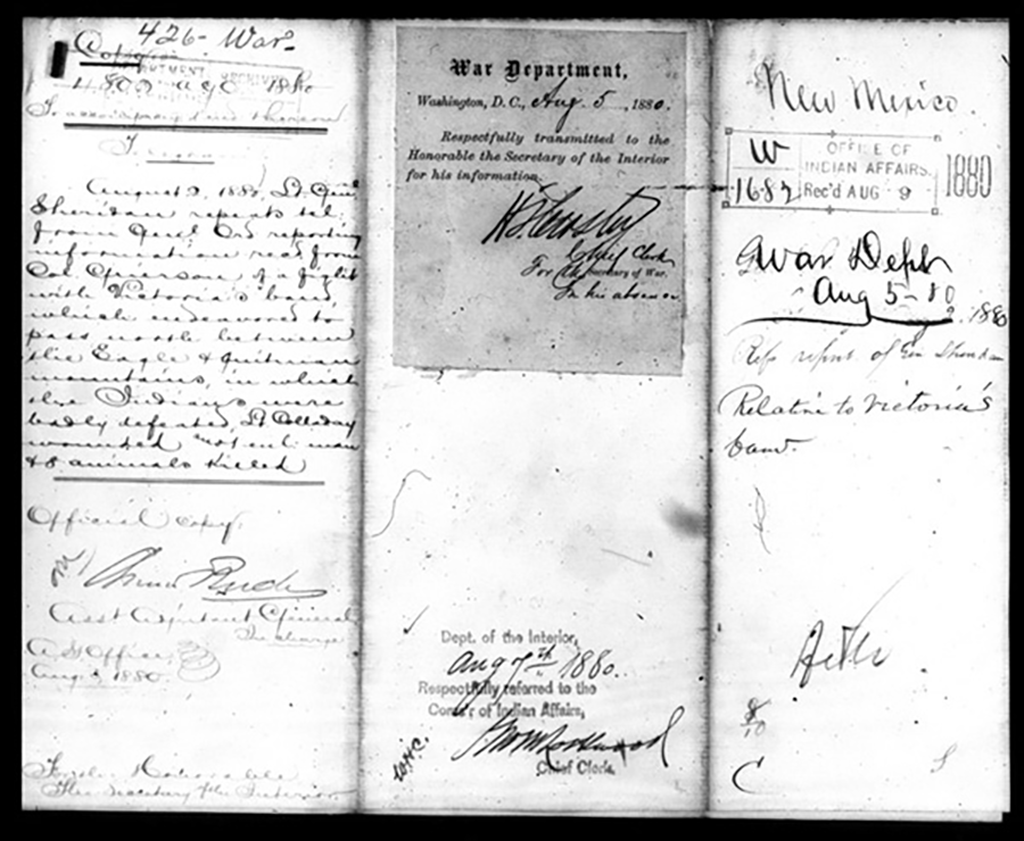

Courtesy of Library of Congress

Rather than face certain death at San Carlos, Victorio once again fled with his people. This time they headed southward into Chihuahua. Despite one final attempt to negotiate a return to Warm Springs in the summer of 1879, Victorio never again submitted to U.S. or Mexican authorities.

By the early fall of 1879, U.S. military officials had lost track of Victorio’s band. From Chihuahua, governor Luís Terrazas complained that Chiricahua raiding intensified because they received supplies on the U.S. side of the border. The people of the New Mexican town of Monticello (formerly known as Cañada Alamosa, near the Warm Springs Agency) had a long history of cooperation with Victorio, and they continued to supply Chihenne messengers after their flight from the reservation system. At the same time, however, many southern New Mexican ranchers claimed that Apache raiding was sustained by Mexican traders.

Courtesy of Municipio de Chihuahua

Major Albert P. Morrow quickly realized that his forces were at a disadvantage against the Chihennes’ intimate knowledge of southern New Mexican landscapes. Due to the headman’s decision to travel in Mexico, the military campaign that led to his death at Tres Castillos was led by the aging Chihuahua Apache fighter, Colonel Joaquín Terrazas.

Following reports that Victorio’s men had perpetrated a double massacre in the Sierra de Candelaria north of Villa Ahumada in Chihuahua, Terrazas was called out of retirement by his cousin, Governor Luís Terrazas. With his second-in-command, Juan Mata Ortíz (jefe político of Janos), Colonel Terrazas engaged in a campaign that lasted nearly a year, from November 1879 to October 1880.

Not long after they began to recruit men into service against the Chihenne, Terrazas and Mata Ortíz learned that Victorio’s band had raided livestock from La Ascensión. Between the fall of 1879 and the spring of 1880 Victorio led his band back and forth across the border where he and his people took refuge in their sacred mountains and resupplied by calling on their allies in places like Monticello. For a time Victorio also split his forces, and one group of Chihennes, headed by Nana, engaged Texas Rangers in the Big Bend region. Through it all, the border provided a means of escaping one army by passing into the neighboring nation.

By the hot, dry summer of 1880 pressure from all sides began to multiply. Most important, the U.S. Consul at Ciudad Chihuahua suggested that Governors Luis Terrazas and Lew Wallace create “a private arrangement . . . for a mutual crossing of the border in order to pursue and fight the Apaches, who, according to the general impression in northern Mexico, ‘have killed one hundred and fifty persons within the past six weeks.’”15 The governors took the consul’s advice, which proved devastating to Victorio. Just after the agreement was struck, Chihennes were forced to battle a combined force of Mexican and U.S. soldiers near Janos.

Courtesy of Jill M. D’Andrea

Not long after the border-crossing arrangement, Mexican forces under Terrazas and Mata Ortíz conducted what proved to be the final siege against Victorio in October of 1880. Although fall had arrived, conditions in northern Chihuahua continued to be unseasonably dry. Victorio’s band and Terrazas’ forces alike were forced to travel in highly difficult conditions, always in search of tinajas (watering holes).

After Victorio met in council with Kaytennae, Nana, and Mangus, the group decided to seek temporary refuge at Tres Castillos, about ninety miles north of Ciudad Chihuahua along the thoroughfare that connected that city with Ciudad Juárez (still known at that time as El Paso del Norte). Victorio knew that the three volcanic protrusions of Tres Castillos guarded a small lake and a supply of grass. After taking a short time to rest and recuperate, the plan was to join Juh’s band in the Blue Mountains of the Sierra Madres.

Terrazas’ troops tracked the Chihennes to Tres Castillos, however. On the morning of October 15, 1880, Terrazas split his forces and surrounded Victorio’s band in their place of refuge. Battle broke out that afternoon and lasted well into the night. At about 10:00 p.m., a few Chihennes set a brushfire in an attempt to distract the Mexican forces but their efforts were in vain.

The Apaches fought almost to the last man: sixty-two warriors lay dead along with sixteen women and children. In the aftermath, Terrazas rounded up sixty-eight prisoners and one-hundred-and-twenty horses. Not until he began to survey the carnage did the colonel realize that Victorio lay among the dead. The head of the Tarahumara detachment in Terrazas’ forces, Mauricio Corredor, received the credit for slaying the great Chiricahua headman.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

The result of the massacre at Tres Castillos was that the Chiricahua people were forever wrested from the lands that the creator Ussen had granted them. In order to establish the sovereignty of the United States and Mexico on their respective sides of the international border, they dispossessed the Chiricahuas of their homelands, restricting the survivors to the desolate San Carlos Reservation. Survivors of Tres Castillos eventually joined the Mescaleros in south-central New Mexico, and those who decided to hold out with Juh and Geronimo (who eventually surrendered in 1886) were relocated first to Florida and then to a reservation at Fort Sill, Oklahoma.

During the conflict between Juh’s and Geronimo’s bands and U.S. and Mexican soldiers, the Chiricahuas specifically targeted and brutally murdered Mata Ortíz in retaliation for his leading role in the dispossession of their people. Although small-scale raiding continued into the twentieth century, 1886 marked the final conquest of the U.S.-Mexico borderlands from the perspective of each nation’s military. Much of our knowledge of Victorio’s movements comes through Mexican and U.S. military records, as the above discussion indicates. Despite the bias of the records, it is possible to trace the ways in which Chiricahuas attempted to maintain their homelands.

Courtesy of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton Archives, WC064

Victorio’s band and the first residents of La Ascensión pragmatically used the border to their advantage. Chihuahua officials considered asensionenses to be promoters of “civilization” in contrast to “savage” Chiricahuas. On the other hand, Apaches believed that the violence perpetrated against them was little more than a series of savage acts. As always, perspective is crucial to understanding past events. In the case of the “Apache Wars” the consideration of multiple perspectives is particularly important. The viewpoint of Victorio’s people helps us to see the violence of the U.S. conquest of the American Southwest, a reality that is glossed over by more benign explanations based on notions of Manifest Destiny. Ironically, some of the very soldiers that fought to “pacify” the Chiricahuas were themselves victims of racism and discrimination.

The establishment of railroad towns like Deming also provide important evidence of the ways in which different groups of people understood the results of the campaign against Victorio’s people. As the Chiricahuas sought to regroup and preserve their culture at the Mescalero agency in hopes of regaining their claim to the Warm Springs in the future (a hope that they have never relinquished), U.S. politicians and developers concluded that New Mexico was now safe for capitalist development. It was no accident that Deming, at the junction of the Atchison, Topeka, & Santa Fe and Southern Pacific lines, was incorporated in 1881—just after Victorio’s death. The ethnocentric actions of many American settlers, prospectors, railroaders, and investors reflected their belief that civilizing forces had created stability in New Mexico and the U.S.-Mexico borderlands.