The History of New Mexico

Collapse

Expand

-

Chapter 13: The Great Depression & The New Deal

- The Great Depression & The New Deal

- Artist Colonies & Rural Reformers

- Depression Comes to New Mexico

- Dennis Chávez & The Hispanic New Deal

- Indian New Deal & Navajos

- References & Further Reading

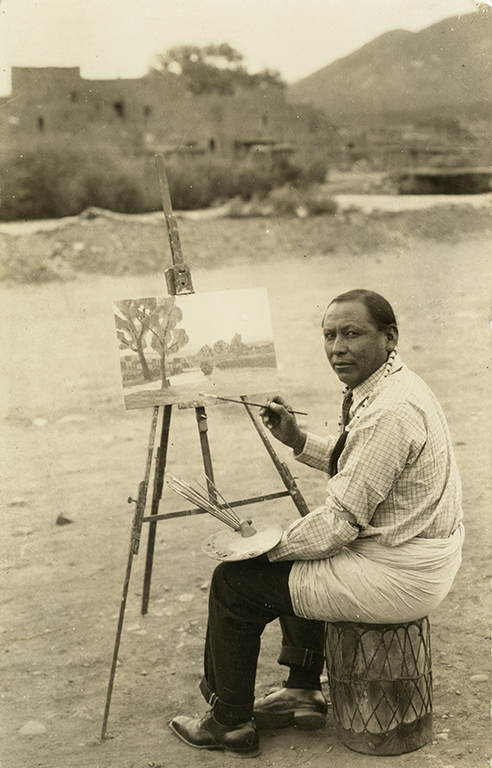

The growth of tourism and artist colonies—especially in Taos and Santa Fe—during the first decade of the twentieth century emphasized the staggering economic disparity between the wealthy and the poor in New Mexico. In part, the attitudes of Anglo artists, writers, and cultural reformers served to perpetuate the economic and ethnic divides that troubled the new state. The outsiders saw New Mexico’s “indigenous peoples” (they applied the term to nuevomexicanos and Native Americans alike) as adherents of a “primitive,” pre-industrial way of life. It was precisely that element of their lifeways that drew the artists to them, as had been the case with the rise of the tourism industry. The creation of artwork that portrayed New Mexico’s peoples and landscapes were a key element of the tourism project promoted by the Santa Fe Railroad and the Fred Harvey Company.

Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 006711.

As the jointure battle raged in the Senate in 1906, another important piece of legislation for New Mexico was also passed: the Antiquities Act. Edgar Lee Hewett provided key funding and support through his political and economic connections in the East. Hewitt was an archeologist by training, and he was instrumental in the formation of Santa Fe’s unique Pueblo Revival architectural style and he spearheaded the creation of the Museum of New Mexico.

As Santa Fe remade itself along cultural lines, a group of wealthy Eastern artists and reformers arrived in northern New Mexico. In an attempt to alleviate the excesses of modern America, they looked to the native peoples of New Mexico as an example of what it meant to be American. Certainly, the irony of such assertions was not lost on New Mexicans who had been consistently denigrated as un-American since 1848. Reformers’ misconceptions of New Mexico’s problems, coupled with the racism, romanticism, and cultural initiatives of the 1930s, resulted in momentary relief for New Mexico’s economic woes that did not address larger structural issues that might have allowed the state’s peoples to finally enjoy both full U.S. citizenship and economic autonomy.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

In 1917, a young woman named Mabel Sterne arrived in New Mexico for the first time. She was the epitome of the early twentieth century New Woman, and she was well connected to artistic and literary movements in Greenwich Village and Europe. Her husband, Maurice Sterne, told her that a visit to New Mexico would change her life. He was right. As Mabel herself characterized the experience: “My life broke in two right then, and I entered into the second half, a new world that had replaced all the ways I had known with others.”2 Not long thereafter, she sent her husband away and began an affair with Taos Pueblo artist Tony Lujan. She is known to history by her last married name, Mabel Dodge Luhan.

Luhan and other artists, writers, and reformers belonged to a generation that was discontented with modern life and technologies, especially in the form of munitions and weapons used to kill millions of young men in European trenches during World War I. Anti-modernists believed that modern innovations had morally bankrupted Western societies. Urban problems, including pollution, overcrowding, and poor working conditions, further convinced them that modern life was deeply troubled. Yet they only took their criticisms so far. Elements of modernity that they did not deem destructive, such as transportation innovations, electricity, running water, and so on, were acceptable.

Charles E. Lord (photographer). Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 028817.

In New Mexico Mabel Dodge Luhan found a place that appeared not to have been touched by the advances of modernity. She and others, such as the Taos Society of Artists, Mary Austin, and John Collier, believed that nuevomexicano villages and Native American communities represented the “lost soul of America.” They believed that Americans living in other areas of the United States had much to learn from New Mexican villagers.

Their perceptions of New Mexico and its peoples were based on four notions that were widely held during their lifetime. First, was the idea that humans in preindustrial villages lived in harmony with the environment and their neighbors in a type of simple equity. Second, people who lived agricultural lifestyles were supposedly inherently “honest, virtuous, industrious, frugal, pious, and incorruptible.”3 Such beliefs dated back to Thomas Jefferson’s idealization of the United States as a nation of yeoman farmers.

Third, people who lived close to nature were considered closer to God, “who was embodied in nature.”4 And, fourth, artists, writers, and reformers, viewed New Mexico through the lens of the melting pot, an idea that is still discussed in present-day American society, although scholars have heavily critiqued it. When early twentieth-century observers framed the United States as a melting pot, they declared it to be a place where people of various ethnic and cultural background came together to become “Americans”—a term whose meaning is quite slippery and continuously debated.

The caveat held by adherents of the melting pot ideal was that “ethnic and national differences enriched the nation culturally as long as they were not allowed to impede it economically or politically.”5 As our study of the territorial period suggests, U.S. politicians consistently characterized nuevomexicanos and Native Americans as two groups of people whose cultural backgrounds threatened to hold the nation back in terms of economic and political progress.

Luhan and her contemporaries, however, saw in New Mexico’s peoples and cultures a means of restoring elements of American culture and morality that were lost to modernization. Their highly romanticized notions of New Mexican villages drew clear distinctions between what they considered to be the good and the bad aspects of village life. Cooperative, communitarian values, which were often overstated by the outside observers, were considered positive attributes in need of preservation against the onslaught of modern life.

At the same time, artists, writers, and reformers found some elements of village life to be evidence of inefficiency and waste. Like Protestant missionary women who worked among nuevomexicanas in the first two decades of the twentieth century, they believed that outmoded agricultural practices, Catholic “superstition,” lack of ambition, and general ignorance plagued nuevomexicanos. Such problems needed to be addressed through education on the latest farming techniques and technologies, new methods of food preservation, and homemaking and child rearing advice. The missionaries actively worked to alter nuevomexicano traditions, yet, ironically, the reformers who claimed they were working to preserve the villages also attempted to update elements of village life along similar lines.

Mabel Dodge Luhan’s relationship with her husband Tony serves as a microcosm of the ways in which her cultural initiatives had both positive and negative impacts on New Mexicans. In order to marry Mabel, Tony divorced his wife and violated tribal custom by marrying a white woman. Their relationship was troubled, as each strong personality attempted to promote his or her own interests. Tony gained wealth, power, and a reputation as an Indian sage through his association with Mabel, but he burned bridges with his own people in the process.

Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 134744.

Mabel’s description of her marriage to her Anglo American friends is also telling. She took Tony’s name, but changed the spelling of Lujan to “Luhan” in order to prevent pronunciation errors among her elite Eastern American friends and family. In her own memoirs, she presented herself as an example of the decline of modern American civilization and Tony “and the Pueblo Indians as the vehicle for rebirth offered by the Indian Southwest.”6 Much like the way she altered her married name, her efforts to preserve Pueblo and hispano cultures through art and writing reproduced those cultures in an altered form in order to satisfy Anglo American sensibilities. By inviting a seemingly endless influx of writers and artists to her Taos home, however, Luhan “put Taos on the map.”7

Over time, Tony regained the respect of some within his Pueblo due to the political activism of Luhan’s group of Anglo writers, artists, and reformers. She introduced British author D. H. Lawrence, and painters Andrew Dashburg, Ward Lockwood, Cady Wells, and Louis Ribak to New Mexico. Each of them found that New Mexico’s peoples and landscapes filled voids in their individual work. Despite their enchantment with New Mexico, Luhan’s domineering presence alienated them as well. To escape her attempts to shape his writing, Lawrence moved away from her lavish and spacious Taos home to a remote location in the mountains to the north.

Luhan also forged ties with reformers Mary Austin and John Collier. Like the artists and writers who were drawn to New Mexico, Austin and Collier felt a deep sense of dissatisfaction with the excesses of modern society. In the Native American and hispano villages of New Mexico they found communal values and cooperation that they believed could stand as an example for urban communities elsewhere in the United States and Europe. Their admiration for nuevomexicanos and Pueblos translated into a form of mimicry that historians, like Phillip J. Deloria, have termed “playing Indian.”8

T. Harmon Parkhurst (photographer). Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 118455.

In Mary Austin’s case, her fascination with New Mexico led her to “play villager.” Prior to her arrival in Taos in 1919, Austin was already a nationally known writer and activist. In the context of the post-World War I Red Scare, she sought alternatives to both U.S. capitalism and Russian communism. Indigenous and hispano villages operated on a type of localized socialism that she found appealing. Indeed, in 1925, she wrote that the community and egalitarian values of people in the Southwest “would fill the self-constituted prophets of all Utopias with unmixed satisfaction.”9

Photograph by Charles Fletcher Lummis

Austin and many other reformers interested in New Mexican villages had also spent time in Mexico in the 1920s as that nation attempted to recreate itself following the violent phase of the Mexican Revolution. Philosopher José Vasconcelos used his position as head of the Department of Public Education (Secretaría de Educación Publica) to initiate a series of cultural missions that focused on improving education in rural areas. Under the motto of “educar es redimir” (to educate is to redeem), the new education system fostered literacy as well as a sense of Mexican nationalism based on indigenous peoples and their lifeways.10

Teachers not only had the responsibility of helping rural Mexicans learn to read and improve their skills, they also taught the history of the revolution in a way that supported the legitimacy of President Alvaro Obregón’s administration. Vasconcelos posited the idea of the Cosmic Race (la raza cósmica) to counter international racist assumptions that Mexico’s people were somehow backward in intellectual and physical terms due to the high level of mestizaje in the nation’s history. Instead, Vasconcelos and rural teachers expressed an alternative characterization that stressed the strength of people with mixed heritage. Through the cultural missions, Mexican administrators sought to create their own distinct meaning of Mexican citizenship that centered on the vitality of indigenous and mestizo culture, as well as the purported gains of the revolution.

A series of intellectuals, including D.H. Lawrence, Katherine Anne Porter, Waldo Frank and John Dewey visited Mexico to observe and evaluate the Mexican educational system’s attempt at cultural engineering. Based on their observations, Mary Austin and her associate Lloyd Tireman attempted to adapt the concept of the Mexican cultural missions to fit the needs of New Mexican villages.

Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 185034.

Following up on her work in association with Edgar Lee Hewett and Frank Applegate to create the Indian Arts Fund and the Spanish-Colonial Arts Society in 1925, Austin supported Tireman, professor of elementary education at the University of New Mexico (UNM), in the creation of the San José Experimental School. Located in Albuquerque’s South Valley, the school was to serve the dual purpose of studying “the educational potential of Spanish-speaking school children under controlled conditions, and to train teachers for the rural elementary schools of the state.” Austin believed that nuevomexicano children held a great capacity for learning until age fifteen, when “the racial inheritance rises to bind them to patterns of an older habit of thinking.”11

The San José Experimental School took cues from the Mexican system of cultural missions, but from a different angle. Whereas Vasconcelos focused on integrating indigenous and rural communities into mainstream Mexican life, Austin and Tireman—along with other Anglo American artists, writers, and reformers—sought to create boundaries around New Mexican villages to protect them from mainstream, modern culture. By their estimation, villages should stand apart as role models to the rest of the nation.

In the process, however, the rural teachers trained at the San José Experimental School prepared to teach villagers how to adopt modern techniques of food preservation—canning rather than drying fruits and vegetables—and forms of hygiene and child rearing that were practiced in the Eastern United States. Much like Protestant missionary women and agents of assimilation programs that targeted Mexican immigrant mothers throughout the Southwest, Austin’s fascination with nuevomexicano villages was tempered by the desire to further the benefits of modernization while simultaneously critiquing modernization’s excesses.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

John Collier’s activities among Pueblo peoples was also defined by the same paradox. Much like Mabel Dodge Luhan, Collier experienced a life-changing transformation when he spent time among the people of Taos Pueblo in 1920. In particular, he noted the ways in which Taos people balanced the needs of individuals against that of the community. They also seemed to live in harmony with animals and the natural environment in ways that Collier had never before observed. During the 1920s, he vocally opposed federal policies of Indian assimilation, and during the New Deal era he became head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. In that capacity, his advocacy for Native American people took a back seat to his desire to simultaneously modernize indigenous lifeways, as will be discussed below.

In certain respects the actions of artists, writers, and reformers had a positive impact on nuevomexicanos and Native Americans. Figures like Luhan, Austin, and Collier promoted an understanding of New Mexico and its peoples beyond the racist notions that had characterized the territorial period. Their initiatives boosted literacy in the state and helped to preserve cultural practices that were threatened by the onslaught of the modern, capitalist economy.

Steve Northup (photographer). Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 010909.

Reformers and artists also problematically characterized New Mexico as a place that remained untouched by the national capitalist economy. In creating their works, they exploited the extremely cheap labor provided by Pueblos and nuevomexicanos who worked for them as models, maids, and servants. In putting New Mexico “on the map,” they increased the value and costs of the very lands and resources that they idealized. Their admiration for New Mexican cultures promoted and facilitated their commodification.

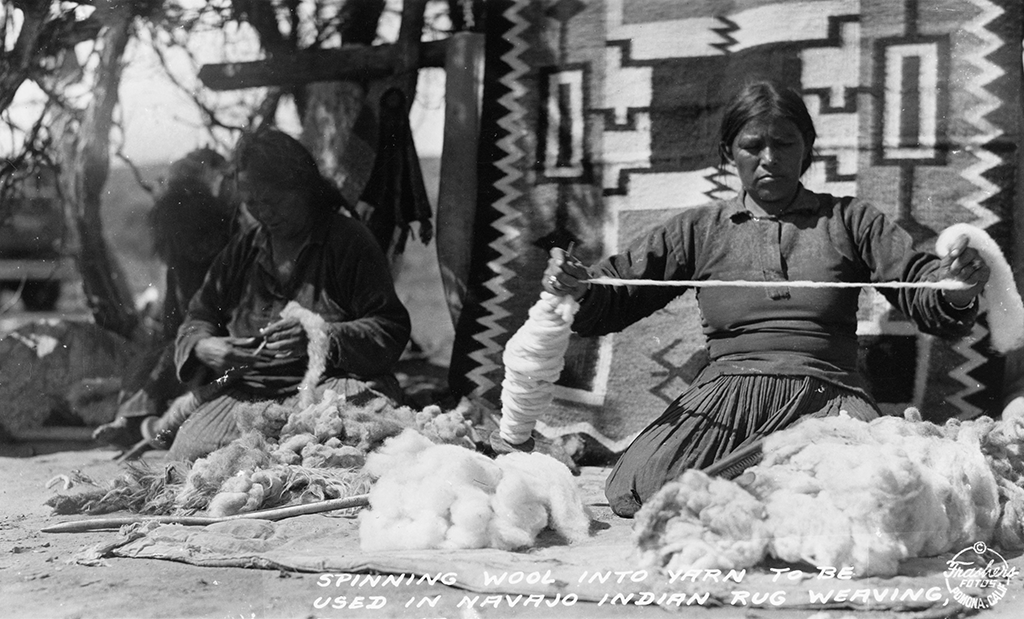

Ironically, by the 1930s Anglo reformers inserted themselves in nuevomexicano and Native American communities as caretakers of cultural authenticity. As outsiders, they more typically created the cultural ideals that they were ostensibly there to preserve. One striking example involves reformers’ efforts to restore authenticity to Navajo weaving practices. New Deal agents realized that Navajo weavers used synthetic fibers and artificially produced dyes instead of wool and dyes extracted from local plants.

Frasher (photographer). Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 074988.

Under the auspices of the WPA, agents “retaught” Navajos to use “authentic” materials in weaving. Navajos had turned to synthetic materials because they were cheaper and they made weaving more efficient. Indigenous and nuevomexicano communities were far more integrated into the national capitalist economy than reformers wished to realize. The reformers did not comprehend the extent to which their actions among Native Americans and nuevomexicanos were selective and highly arbitrary.