Oral Presentations

A common assignment in technical writing courses—not to mention in the workplace—is to prepare and deliver an oral presentation, a task most of us would be happy to avoid. However, while employers look for coursework and experience in preparing written documents, they also look for experience in oral presentations as well. Look back at the first chapter to refresh your memory on how important interpersonal communication skills are in the workplace.

If you can believe the research, most people would rather have root canal surgery without novocaine than stand up in front of a group and speak. The task of public speaking is truly one of the great stressors. But with some help from the resources that follow, you can be a champion presenter.

When you finish this chapter, you should be able to plan and prepare a talk or presentation, deliver the presentation, create presentation materials that reflect standards of effective presentation, and evaluate presentations delivered by others, including classmates.

Contents and Requirements for the Oral Presentation

The focus for your oral presentation should be clear before you begin. Make sure your goal for the presentation is clear; then, you can begin working to create an understandable presentation which requires you to organize, plan, and time your discussion in a way to engage and persuade your audience. You don’t need to be Mr. or Ms. Slick-Operator—just present the essentials of what you have to say in a calm, organized, well-planned manner.

When you give your oral presentation, your listeners will be seeking similar outcomes. Use the following as a requirements list to focus your preparations:

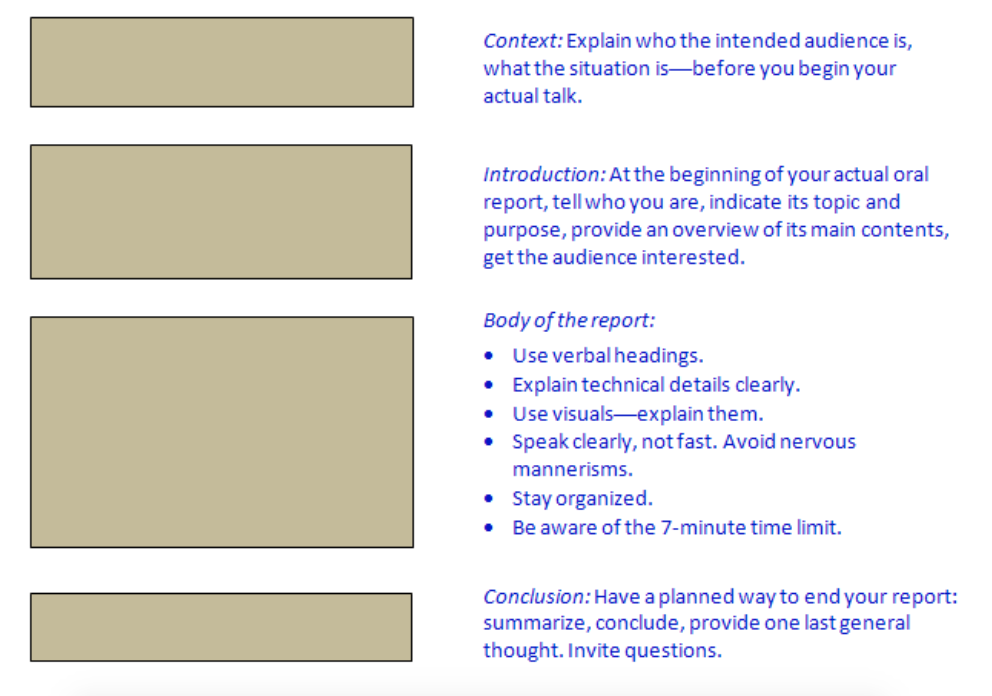

- Plan to explain what the situation of your oral report is, who you are, and who the audience is. Make sure that there is a clean break between this brief explanation and the beginning of your actual oral report.

- Make sure your oral report lasts no longer than the time allotted.

- Pay special attention to the introduction to your talk. This is where you tell your audience what you are going to tell them.

- Indicate the purpose of your oral report

- Give an overview of its contents

- Find some way to interest the audience

- Use a visual design software—preferably a slide software (such as Powerpoint, Prezi, Google Slides). Use visuals to compliment your text and keep your audience engaged.

- Create slides with minimal text. Some tips to reduce text is to create bullet lists that use verb-led phrases. Also, avoid including complete sentences or slides with more than six lines of text.

- Make sure you discuss key elements of your visuals. Don’t just throw them up there and ignore them. Point out interesting or important aspects; explain them to the audience.

- Plan to explain any technical aspect of your topic clearly and understandably. Don’t race through complex, technical content—slow down and explain it carefully so that your audience will understand it.

- Use “verbal headings”—at this point in the course, you’ve become a pro at using headings in your written work. There is a corollary in oral reports. With these, you give your audience a clear signal you are moving from one topic or part of your talk to the next. Your presentation visual can signal your headings.

- Plan your report in advance and practice it so that it is organized. Make sure that listeners know what you are talking about and why, which part of the talk you are in, and what’s coming next. Overviews and verbal headings greatly contribute to this sense of organization.

- End with a real conclusion. People sometimes forget to plan how to end an oral report and end by just trailing off into a mumble. Remember that in conclusions, you can:

- summarize (go back over high points of what you’ve discussed)

- conclude (state some logical conclusion based on what you have presented)

- provide some last thought (end with some final interesting point but general enough not to require elaboration)

- or some combination of these three

- And certainly, you’ll want to prompt the audience for questions and concerns.

- As mentioned above, be sure your oral report is carefully timed. Some ideas on how to work within an allotted time frame are presented in the next section.

Effective Oral Presentations

An effective oral presentation is more about creative thinking on your feet and basic skills than about wearing good shoes and knowing how to turn on the computer projector. Allow the presentation to remind you of your key points rather than using the presentation slides to outline every single idea and statement you plan to share. Companies have long cried for graduates who can give dynamic talks, and they have long relied on presentations as a key way to sway concerned parties towards a desired outcome. But many presenters make the mistake of trying to let the computer, bells and whistles blaring, do all the work for them. They forget the fundamentals of oral presentation, and thus whatever polish they have quickly loses its luster.

To become a modern speaker worth listening to, whether you’re serving as a company representative or presenting at a conference, you must come fully prepared, engage your audience’s attention and memory, read the audiences’ reactions, attend to some visual design basics, and take stock of how you come across as a speaker.

Preparing for a Talk

There’s a rule-of-thumb in carpentry: Measure twice, cut once. The tenets behind this principle should be obvious—once a mistake is made, it’s difficult or impossible to undo. Though the carpenter can usually spackle or glue to repair, as a speaker you simply cannot get back those three minutes you just wasted in a fifteen-minute presentation. The following preparation principles will keep you right on track.

- Practice your talk straight through, and as you go, jot quick notes to yourself about how to improve it. If you cannot manage to practice your talk straight through, perhaps you are not yet ready to offer it.

- Ideally, practice your talk under conditions similar to those in which you will give it, considering such factors as acoustics, distance from the audience, lighting, and room size. Lighting becomes especially important when computer equipment is involved. Be mentally prepared to adapt to the environmental conditions.

- As a draft, present your talk to a friend or two first and have them critique it. If you’re gutsy and can tolerate the unforgiving lens of the camera, record your practice talk and critique it afterwards.

- View all of your visuals from your audience’s perspective prior to your talk. Be sure that your audience can easily see all that you want them to see, especially material that appears in the lower half of the screen.

- When you speak professionally, always request presentation guidelines from any relevant organizations and conform to them explicitly. It would be embarrassing for you if you were expected to present units in metric, for example, and you did otherwise because you failed to request or follow the available guidelines.

- As part of your preparation, choose an appropriately engaging and helpful title. You are expected not to come off as dull and uninspired. Which talk would you rather attend: “Specific Geometrical Objects with Fractional Dimensions and Their Various Applications to Nature in General and The Universe At Large as we Know it” or “And On The Eighth Day, God Created Fractals”?

- Become highly familiar with any technology you’ll be using. Practice with the actual hardware or type of hardware you’ll be working with, making sure that compatibility or speed issues don’t get in your way. I’ve seen students go to present at a conference with a USB version of their presentation confidently in hand, only to find that the computer they were using could not open it. If websites are needed as part of your presentation, check connection speeds and make sure all URLs are up and running.

Preparing for the Oral Presentation

Pick the method of preparing for the presentation that best suits your comfort level with public speaking and with your topic. However, plan to do ample preparation and rehearsal—some people assume that they can just jump up there and ad lib for so many minutes and be relaxed and informal. It doesn’t often work that way—drawing a mental blank is the more common experience. A well-delivered presentation is the result of a lot of work and a lot of practice.

Here are the obvious possibilities for preparation and delivery:

- Write a script, practice it; keep it around for quick-reference during your talk.

- Set up an outline of your presentation; practice with it, bring it for reference.

- Set up cue cards, practice with them, and use them during your talk.

- Write a script and prepare by reading from it until you are comfortable giving the presentation without the script.

Of course, the extemporaneous or impromptu methods are also out there for the brave and the adventurous. However, please bear in mind that people will be listening to you—you owe them a good presentation, one that is clear, understandable, well-planned, organized, and on target with your purpose and audience.

It doesn’t matter which method you use to prepare for the talk, but you want to make sure that you know your material. The head-down style of reading your report directly from a script has problems. There is little or no eye contact or interaction with the audience. The delivery creates a dull, boring monotone that either puts listeners off or is hard to understand. And, most of us cannot stand to have reports read to us!

For many reasons, most people are nervous when they give oral presentations. Being well prepared is your best defense against the nerves. Try to remember that your classmates and instructor are a forgiving, supportive group. You don’t have to be a slick entertainer—just be clear, organized, and understandable. The nerves will wear off someday, the more oral presenting you do. In the meantime, breathe deeply and enjoy.

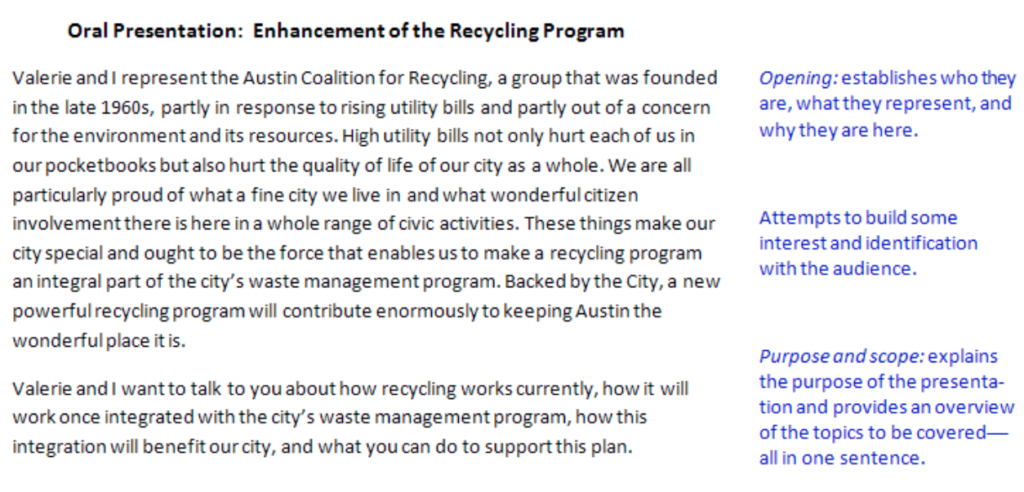

The following is an example of an introduction to an oral presentation. You can use it as a guide to planning your own.

Delivering an Oral Presentation

When you give an oral report, focus on common problem areas such as these:

- Timing—Make sure you keep within the time limit. Finishing more than a minute under the time limit is also a problem. Rehearse, rehearse, rehearse until you get the timing just right.

- Volume—Obviously, you must be sure to speak loud enough so that all of your audience can hear you. You might find some way to practice speaking a little louder in the days before the oral presentation.

- Pacing, speed—Sometimes, oral presenters who are nervous talk too fast. All that adrenaline causes them to speed through their talk, making it hard for the audience to follow. In general, it helps listeners understand you better if you speak a bit more slowly and deliberately than you do in normal conversation. Slow down, take it easy, be clear…and breathe.

- Gestures and posture—Watch out for nervous hands flying all over the place. This too can be distracting—and a bit comical. At the same time, don’t turn yourself into a mannequin. Plan to keep your hands clasped together or holding onto the podium and only occasionally make some gesture. Definitely keep your hands out of your pockets or waistband. As for posture, avoid slouching at the podium or leaning against the wall. Stand up straight, and keep your head up.

- Verbal crutches—Watch out for too much “uh,” “you know,” “okay” and other kinds of nervous, verbal habits. Instead of saying “uh” or “you know” every three seconds, just don’t say anything at all. In the days before your oral presentation, practice speaking without these verbal crutches. The silence that replaces them is not a bad thing—it gives listeners time to process what you are saying.

The following is an example of how topic headings can make your presentation easy for your listeners to follow.

Planning and Preparing Visuals for Oral Presentations

Prepare at least one visual for this report. Here are some ideas for the “medium” to use for your visuals:

- Presentation software slides—Projecting images (“slides”) using software such as Powerpoint has become the standard, even though maligned by some. One common problem with the construction of these slides is cramming too much information on individual slides. A quick search on terms like Powerpoint presentation will enable you to read about creating these slides and designing them intelligently. Of course, the room in which you use these slides has to have a computer projector.

- Posterboard-size charts—Another possibility is to get some posterboard and draw and letter what you want your audience to see. Of course, it’s not easy making charts look neat and professional.

- Handouts—You can run off copies of what you want your listeners to see and hand them out before or during your talk. This option is even less effective than the first two because you can’t point to what you want your listeners to see and because handouts distract listeners’ attention away from you. Still, for certain visual needs, handouts are the only choice. Keep in mind that if you are not well prepared, the handouts become a place for your distracted audience to doodle.

- Objects—If you need to demonstrate certain procedures, you may need to bring in actual physical objects. Rehearse what you are going to do with these objects; sometimes they can take up a lot more time than you expect.

Avoid just scribbling your visual on the chalkboard or whiteboard. Whatever you scribble can be neatly prepared and made into a presentation slide or posterboard-size chart. Take some time to make your visuals look sharp and professional—do your best to ensure that they are legible to the entire audience.

As for the content of your visuals, consider these ideas:

- Drawing or diagram of key objects—If you describe or refer to any objects during your talk, try to get visuals of them so that you can point to different components or features.

- Tables, charts, graphs—If you discuss statistical data, present it in some form or table, chart, or graph. Many members of your audience may be less comfortable “hearing” such data as opposed to seeing it.

- Outline of your talk, report, or both—If you are at a loss for visuals to use in your oral presentation, or if your presentation is complex, have an outline of it that you can show at various points during your talk.

- Key terms and definitions—A good idea for visuals (especially when you can’t think of any others) is to set up a two-column list of key terms you use during your oral presentation with their definitions in the second column.

- Key concepts or points—Similarly, you can list your key points and show them in visuals. (Outlines, key terms, and main points are all good, legitimate ways of incorporating visuals into oral presentations when you can’t think of any others.)

During your actual oral report, make sure to discuss your visuals, refer to them, guide your listeners through the key points in your visuals. It’s a big problem just to throw a visual up on the screen and never even refer to it.

As you prepare your visuals, look at resources that will help you. There are many rules for using PowerPoint, down to the font size and how many words to put on a single slide, but you will have to choose the style that best suits your subject and your presentation style.

The two videos that follow will provide some pointers. As you watch them, make some notes to help you remember what you learn from them. The first one is funny…Life After Death by PowerPoint by Don McMillan, an engineer turned comedian.

You may also have heard about the presentation skills of Steve Jobs. The video that follows is the introduction of the iPhone…and as you watch, take notes on how Jobs sets up his talk and his visuals. Observe how he connects with the audience…and then see if you can work some of his strategies into your own presentation skills. This is a long video…you don’t need to watch it all, but do take enough time to form some good impressions.

Attributions

- Technical Writing, 11.5 Slides and PowerPoint Presentations by Allison Gross, Annemarie Hamlin, Billy Merck, Chris Rubio, Jodi Naas, Megan Savage, and Michele DeSilva is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

- Sexy Technical Communication – “Oral Presentations.” by David McMurray and Cassandra Race. iBooks.

Slides, PowerPoint Presentations, and Preparing for a Talk

Microsoft introduced PowerPoint in 1990, and the conference room has never been the same. Millions were amazed by the speed with which a marketing professional or an academic could put together a consistent, professional-looking slide presentation. And then…

At some point, somebody with critical thinking skills asked a great question: “Do we really need all these slide shows?” The stock images of arrows, business people in suits, stick figures scratching their heads, and the glowing, jewel-toned backgrounds eventually looked tired and failed to evoke the “wow” reaction presenters desired.

Microsoft is attempting to refresh the design options for PowerPoint, and there are dozens of good alternatives, some of them free (Keynote, Slide Bureau, Prezi, SlideRocket, Easel.ly, Emaze, Slidedog). But the fundamental problem remains—text-heavy, unfocused, overlong presentations are the problem, not the software. If you are sure that a visual presentation will provide something necessary to your audience, keep the number of slides and the amount of text on each slide to a bare minimum. Think of a slide presentation as a way of supporting or augmenting the content in your talk; don’t let the slides replace your content.

If you had planned to read your slides to the audience, don’t. It’s considered one of the single most annoying choices a presenter can make. Excessively small text and complex visuals (including distracting animations) are frequently cited as other annoyances. Use your presentation slides as a way to engage your audience, introduce key ideas in short phrases, and provide a visual design strategy to help you share the complex information built into your presentation.

Try to design your slides so that they contain information that your viewers might want to write down; for example, good presentations often contain data points that speakers can’t just rattle off or quick summaries of key concepts that viewers won’t be able to make up on the fly. If you can’t explain how the slides add value to your presentation, don’t use them.

To get a feel for what may annoy your audience, try Googling “annoying PowerPoint presentations.” You’ll get a million hits containing helpful feedback and good examples of what not to do. And finally, consider designing your presentation to allow for audience participation instead of passive viewing of a slideshow—a good group activity or a two-way discussion is a far better way to keep an audience engaged than a stale, repetitive set of slides.

Tips for Good Slides

All of the design guidelines in this competency will help you design consistent, helpful, and visually appealing slides. But all the design skill in the world won’t help you if your content is not tightly focused, smoothly delivered, and visible. Slides overloaded with text and/or images will strain your audience’s capacity to identify important information. Complex, distracting transitions or confusing (or boring) graphics that aren’t consistent with your content are worse than no graphics at all. Here are some general tips:

- Simplicity is best: use a small number of high-quality graphics and limit bullet points and text. Don’t think of a slide as a page that your audience should read.

- Break your information up into small bites for your audience, and make sure your presentation flows well. Think of a slide as a way of reminding you and the audience of the topic at hand.

- Slides should have a consistent visual theme; some pros advise that you avoid using the stock PowerPoint templates, but the Repetition and Alignment aspects of CRAP are so important that if you don’t have considerable design skill, templates are your best bet. You can even buy more original-looking templates online if you don’t like the ones provided with the software.

- Choose your fonts carefully. Make sure the text is readable from a distance in a darkened room. Practice good repetition and keep fonts consistent.

- Practice your presentation as often as you can. Software is only a tool, and the slide projector is not presenting—you. Realizing this is half the battle.

Helping Your Audience Remember Your Key Points

Andy Warhol is known for the comment that everyone will be famous for fifteen minutes. If your fifteen minutes of fame is during your oral presentation, you want to be sure not to waste your opportunity. I’m amazed at how many times I’ve sat through a talk and come away with only a vague sense of what it was about. There are many reasons for this—some speakers view their talk as simply a format for reading a paper, while others fill the air with many words but little substance—but the most common reason is the simplest one: the speaker showed uncertainty about the talk’s alleged subject. If you don’t spell out your premise, highlight your key points, and make it easy for your audience to remember the thrust of your presentation, you can’t expect your listeners to come away with understanding and investment.

To ensure an engaged audience for your talk, follow these practices:

- Introduce and Conclude. Use a formal introduction at the beginning of your talk and a summary afterwards to highlight your major points. Make sure your audience can remember your key points by keeping them simple and straightforward—even enumerated.

- Present in Sections. Give your talk “parts”—usually no more than three major parts for practical purposes—and let us know when we’re transitioning from one part to the next. This will help your audience to remain interested and focused.

- Spell out the Objective. Give the talk’s objective and even a hint of the conclusion right up front. Articulate the objective on its own slide so we can’t miss it. Revisit the objective at the end if necessary to underscore how it was realized.

- Use Props. Consider the use of some simple, meaningful props—even pass them around. Props can generate audience interest and, especially if they represent the actual work you did, they make the nature of that work more concrete. I’ve been to great talks where an experimental sample or photographs representing production sites were passed around, and they often generated focused questions from the audience members afterwards.

- Use Handouts. If appropriate, give a handout. As long as it’s well-designed, a concise written summary with bulleted points on a handout will ensure that your talk can be followed throughout. Such a handout should ideally be just one or two pages long, and be sure to time and manage its distribution so that it doesn’t take away attention from you as you speak. One possibility for handouts is an actual printout of your slides through the “Handouts” option in PowerPoint, but be certain that your audience actually needs all of your slides before electing this option.

- Offer Q&A and provide contact information. Create a final slide that welcomes the audience to ask questions and provides your contact information. If question and answer is involved as part of the end of the talk, don’t let any questions deflect our interest. Some audience members might try to draw the attention to themselves, or focus on a mistake or uncertainty in your presentation, or even undermine your authority directly with an intimidating challenge. (I recall one speaker at a professional conference being tossed the strange question, “Your data is crap, isn’t it?”) Remember that the stage and agenda are yours, and it’s your job to keep it that way and end your talk with a bang, not a whimper. If you don’t know the answer to a question, admit it or offer to discuss it privately after the presentation, then move on. One savvy way to handle questions is to turn back to your presentation slides as you answer them—call up a slide that will help repeat or explain the relevant point—and this will remind your audience that your talk had substance.

Mastering the Basics of Slide Design

PowerPoint helps us to think of each projected page as a “slide” in a slideshow. But just as someone else’s home movies can be thoroughly uninteresting if they’re grainy, poor in quality, and irrelevant, PowerPoint slides that are too flashy, cluttered, meaningless, or poorly designed can quickly turn a darkened room full of smart people into a mere gathering of snoozers. As you design your slides, consider these factors:

- Templates. Even though PowerPoint helps you design your slides, don’t assume that someone else’s template will always match your needs. Take charge of slide design by considering first the most efficient way to transmit the necessary information.

- Simplicity. Keep slides as simple and uncluttered as possible, and if the information must be complex, prioritize it for your audience as you present it (e.g., if presenting a ten-column table, direct your audience to the most significant columns). Offer only one major point per illustration. If you need to focus on more than one point, present the illustration in another form on a separate slide with the different point emphasized.

- Titles. Give most slides titles, with a font size of at least 36 points, and body text with a font size of at least 24 points. If you need to cite a source of information, include the citation in a smaller font size at the bottom of your slide.

- Rule of 8s. Apply the “rule of 8s”: include no more than 8 words per line and 8 lines per slide.

- Bullets. When using bulleted lists in slides, present each bulleted line in parallel fashion—i.e., if the first line is a fragment, the others should be as well; if the first line opens with a verb, so should the others.

- Design. Design slides so that their longest dimension is horizontal rather than vertical. Use both uppercase and lowercase letters and orient pictures left to right. Avoid the overuse of animations and transitions, especially audio-based transitions, which can be distracting and downright silly.

- Color. Make sure the color for both the background and text are highly readable, especially under less than optimal lighting conditions. There’s nothing wrong with basic dark lettering and white background for your slides, particularly if they’re text-based. If you do choose a background theme or color, enhance continuity and viewability by keeping it consistent and subtle.

- Images. When possible, replace words with images. Use images in particular when presenting data, demonstrating trends, simplifying complex issues, and visualizing abstractions.

- Spelling. Spelling does count, and you can’t rely on Powerpoint to be an effective proofreader. Be sure your slides are free of grammatical and spelling errors. As Will Rogers quipped, “Nothing you can’t spell will ever work.”

Maintaining the Look and Sound of a Professional Speaker

Public speaking is often cited by people as their number one fear (with death, ironically, as number two.) Clearly, no one overcomes such fear overnight, and no one set of tips can transmogrify you into a polished speaker. However, you can work through that fear by learning from the successes of others. As Christopher Lasch once noted, “Nothing succeeds like the appearance of success.” Good speakers attend first to their wardrobe, dressing as well as their “highest ranking” audience member is likely to dress. An equally important part of looking and sounding like a professional speaker is how you handle your body language and your voice. You must exude confidence if you want to be taken seriously, and remember that a high percentage of your audience’s perception is not about what you say but about how you look when you say it. The following guidelines will help you to look good and sound good as you give a talk:

- Take care not to stand in the way of your own slides—many speakers do this without even realizing it.

- Ideally, use the mouse pointer, a stick pointer, or a laser pointer to draw our attention to a particular item on the screen. One simple circle drawn briefly around the selected information is enough to draw our attention.

- When you are not using a slide directly, keep it out of sight or out of your audience’s line of attention. Turn off the projector or create a dark screen when no visuals are relevant; literally invite your audience to turn its attention away from one idea to another.

- When working with computer projection, do not trust that hardware will always perform as you anticipate. Sometimes equipment fails midstream, or what worked fine for one speaker in a group doesn’t work for the next.

- Don’t forget the value of a good old-fashioned easel or chalkboard. Not only do they offer variety, they are especially good for writing down basic information that you also want your audience to muse over or write down, or for presenting a picture as it evolves via its individual pieces (e.g., a flow chart, schematic, or simple experimental set-up).

- Maintain eye contact with at least a few people—especially those who are being the most responsive—in various parts of the room. Conversely, if you’re especially nervous about one or two audience members or you note some audience members looking sour or uninterested, avoid eye contact with them.

- Refer to time as an organizational tool: “For the next two minutes, I will summarize the city’s housing problem, then I will move on to . . . ” This keeps both you and your audience anchored.

- Use the “point, turn, talk” technique. Pause when you have to turn or point to something, then turn back towards the audience, then talk. This gives emphasis to the material and keeps you connected with audience members. Strictly avoid talking sideways or backwards at your audience.

- Use physical gestures sparingly and with intention. For instance, raise three fingers and say “thirdly” as you make your third point; pull your hands toward your chest slightly as you advocate the acceptance of an idea. Beware, though, of overusing your body, especially to the point of distraction. Some speakers habitually flip their hair, fiddle with their keys, or talk with their hands. I’ve heard some people recommend that speakers keep one hand in a pocket to avoid overusing physical gestures.

- Minimize the amount of walking necessary during your talk, but do stand rather than sit because it commands more authority. As you speak, keep your feet firmly rooted and avoid continual shuffling of your weight. Intentionally leaning slightly on one leg most of the time can help keep you comfortable and relaxed.

- Take care to pronounce all words correctly, especially those key to the discipline. Check pronunciation of ambiguous words beforehand to be certain. It would be embarrassing to mispronounce “Euclidian” or “Möbius strip” in front of a group of people that you want to impress. I once mispronounced the word “banal” during a speech to English professors and one of the audience members actually interrupted to correct me. Most of that speech was—as you might guess—banal.

- Dead air is much better than air filled with repeated “ums,” “likes,” and “you knows.” Get to know your personal “dead air” fillers and eliminate them. Out of utter boredom during a rotten speech a few years ago, I counted the number of times the speaker (a professor) used the word “basically” as an empty transition—44 times in just five minutes. Don’t be afraid to pause occasionally to give your listeners time to digest your information and give yourself a moment for reorientation. To quote Martin Fraquhar, “Well-timed silence hath more eloquence than speech.”

- If you know that you have a mannerism that you can’t easily avoid—such as stuttering or a heavy accent—and it distracts you from making a good speech, consider getting past it by just pointing it out to the audience and moving on. I’ve been to several talks where the speaker opened by saying “Please accept the fact, as I have, that I’m a stutterer, and I’m likely to stutter a bit throughout my speech.” One such speaker even injected humor by noting that James Earl Jones, one of his heroes, was also once a stutterer, so he felt in good company. As you might guess, the following speeches were confidently and effectively delivered, and when the mannerism arose it was easy to overlook.

- Avoid clichés, slang, and colloquialisms, but don’t be so formal that you’re afraid to speak in contractions or straightforward, simple terms. Use visual language, concrete nouns, active single-word verbs. When using specialized or broad terms that might be new or controversial to some audience members, be sure to define them clearly, and be prepared to defend your definition.

- Be animated and enthusiastic, but carefully so—many notches above the “just-the facts” Joe Friday, but many notches below the over-the-top Chris Rock.

Attributions

11.5 Slides and PowerPoint Presentations by Allison Gross, Annemarie Hamlin, Billy Merck, Chris Rubio, Jodi Naas, Megan Savage, and Michele DeSilva is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.