“Language is an app for converting a web of thoughts into a string of words.”

—Steven Pinker, Linguistics, Style and Writing in the 21st Century

My oldest son was two years old and he asked me,

“Where’s the cheeser? I want the cheeser!”

You want cheese? I asked, heading for the refrigerator.

“No, the cheeeeser!”

Oh no. He wants the cheese grater, I thought. How can I distract him? A two-year-old with a cheese grater is just a bad idea. “Let’s play a game!”

“Oh. There’s the cheeser!” he said pointing to the smartphone on the counter.

“Aha!” A cheeser is an object that makes one say “cheese.”

But how did my son come up with this word at two years of age? I never said cheeser in my life, and no one else did for that matter, so he could not just be imitating. I wondered, how can kids who can’t eat, dress, sleep, or poop on their own, figure out something as complex as language? And do other species have language like humans? What even is language exactly?

Language is the principal way in which we convey information to others and how culture is transmitted. As linguists, Bruce Rowe and Diane Levine (2011) explain, “Speech, sign language, and writing is the way that linguistic knowledge gets out of your head and into the heads of others.” Without language, “there would be no stories, there would be no books, there would be no Internet, there would be no computers, in fact, there would be no history” (Jeffrey Elman 2008). Language permits humans to cooperate on massive scales by allowing us to find common ground, pass on information, teach others, and negotiate relationships. Language makes us a powerfully adaptive species. It is no exaggeration to say that the puffs of air that we push out of our lungs and through our vocal tract have changed the world.

What is Language?

Language can be defined as a communication system consisting of words used in a structured and conventional way, but we will see that it is more enlightening to look closely at specific features of language to understand what it is. There is no human society that lacks language, and it is, therefore, a cultural universal. The 7,000 or so languages in the world are wonderfully diverse, with different sounds, words, and rules for making sentences. The !Kung language spoken by the San of the Kalahari, for instance, has one of the largest sound inventories in the world including distinctive click sounds. Different languages use different rules for ordering subjects (S), objects (O), and verbs (V). In English, we say “Sue sells salsa”, an SVO sentence. In Tuareg-Berber, a VSO language, the sentence would be something like “Sells Sue salsa.” There are 6 different possible arrangements for sentences, all of which are found in human languages. Though we often think of language as being spoken, it can have different delivery systems including speech, sign language, and writing. While all cultures have some form of spoken language and accompanying oral traditions, not all have a written form of language. Writing itself had its beginnings around 6,000 years ago, the earliest known writing system, cuneiform, arising in Mesopotamia.

It is easy to take language for granted; most of the time we don’t even think about it. We just do it. If we had to explain it to alien visitors or even to children, we’d probably have trouble even with the basics. Spoken language is communicated through sounds—air pushed up from our lungs through the vocal tract—the area that extends from the vocal cords to the lips where the sounds of language are generated. The shape of the tract affects the shape of the sound produced. Those sounds are combined in systematic ways to make words, which refer

o things, ideas, and relationships. From there, words are combined in systematic ways into phrases, which are combined into sentences. Sound waves then travel through the air, enter the listener’s ear, and are conveyed to the hair cells in the cochlea. From there the signal is transferred to the auditory nerve, then off to the primary auditory cortex in the brain for translation. From an alien perspective, it is a remarkable and complex way to pass along information, and yet even small children can do it.

Features of Language

In 1960, linguist Charles Hockett defined the features of language. He argued that if a communication system lacks even one feature, it is not language. Because language is so essential to human culture, peeling back the layers of language is useful for understanding the nature of being human.

Hockett outlined many design features, but we will consider only six in this chapter. These are:

- Cultural Transmission

- Arbitrariness

- Productivity

- Displacement

- Grammar

- Context-specific

Cultural transmission with regard to language means that humans learn the language of their environment. It is not too surprising that children raised hearing Swahili all around them will grow up to speak Swahili. This was not always so self-evident, however. Psammetichus I, king of Egypt from 664–610 BC, commanded a shepherd to raise two babies without them ever hearing language. Whatever language the babies spoke, Psammetichus reasoned, must be the mother tongue of all languages, from which all other languages descended. One baby allegedly said the word “bekos” which sounded like a Phrygian word for bread, and Psammetichus concluded that Phrygian was the root of all languages. Today, depriving a child of language is called the “forbidden experiment.” Based on the few cases where children are raised without language, it is clear that children do not spontaneously speak a “mother tongue” without ever getting any linguistic input.

Arbitrariness means that words that we assign to represent things don’t resemble each other. In short, words are symbols that represent things or ideas. William Shakespeare’s famous line from Romeo and Juliet “What’s in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet” has come to epitomize the arbitrariness of words. Here’s how Mary Jane Scott, a CNM student explains arbitrariness:

Arbitrariness is the feature of language that says our words don’t necessarily match the things they represent. We have all just decided that in the English language that ‘desk’ represents a desk, but essentially that was just chance. ‘Desk’ could have easily meant something entirely different, but we decided those letters in that arrangement meant what it does, and we’ve just agreed on it.

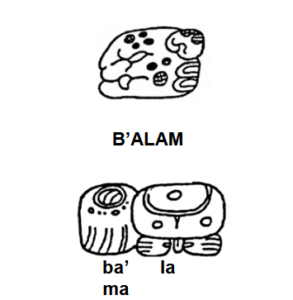

The majority of words in all languages are arbitrary. Sometimes writing systems or signs in American Sign Language are not arbitrary. That is, they resemble the things they represent. Yet, ASL contains arbitrary signs as well. Some writing systems also have non-arbitrary symbols. For example, in the ancient Maya writing system, this is the word for jaguar, which somewhat resembles an actual jaguar. But the spoken word “door” doesn’t resemble a door.

To take another example, “whale” is a small word for a big animal; and “microorganism” is just the reverse. Arbitrariness is what allows different languages to have words that sound nothing like each other—perro, hund, chien, dog. The exception to arbitrariness in spoken language is onomatopoeia in which the word sounds like what it represents. A classic example is “cock-a-doodle-doo”, which resembles the sound a rooster makes. The word for the sound a rooster makes is remarkably similar across unrelated languages and is therefore not arbitrary.

Cock-A-Doodle-Doo–English

Kokekokko–Japanese

Quiquiriquí–Spanish

Cocorico–French

Ake-e-ake-ake–Thai

Productivity means that new words or sentences can be generated. We can always invent new ones. Once upon a time, the words “selfie”, “blog”, and “smartphone” simply didn’t exist. We created them because we needed them to describe the ever-changing world. New sentences can also be created at will. For instance, I could say “Friendly aardvarks do back-flips in pajamas.” Even if you never heard this sentence before, you can still understand it effortlessly. You don’t need to have heard or read this particular combination of words before. You use your knowledge of sentence construction, grammar, and perhaps a little imagination, to figure it out.

Even little children know how to decode language. They don’t just imitate, they also actively construct language. One of the joys of children is that they effortlessly create new words or neologisms. Once my extended family stayed in a Florida condo with a kitchen, three bedrooms, a living room, and even a stash of toys. My five-year-old son decided that this new place wasn’t just a hotel, it was a “home-tel”, creating a totally new, but immediately understandable, word.

Grammar refers to the structural rules of human language. Grammar is essential for understanding and creating language, and is not the trivial rules of language or writing. There are grammatical rules for building words, like adding “ed” or “ing” to form different verbs. Add “er” to “farm” and suddenly you have someone who farms. It is grammar that allows for productivity, creating new words and sentences. Even young children know grammatical rules and do not simply imitate, for instance, when they say “peoples” or “I goed.” Ironically, adults don’t normally say “goed” or “peoples” unless they are imitating their children! We know that children create language from the “Wug Test,” invented by Jean Gleason. Here is how it works:

This is a Wug:

Here are two _____. Obviously, the answer is wugs.

Here’s another:

What would you call a very small wug?

You might have answered with, “wuglet,” or “wugita,” or “wuggie.” If you did, then you are a grammar expert. In addition to systematic rules for organizing sounds into words, every language also has rules for organizing words into sentences. It makes a big difference in meaning whether you say “Bob lied to Mary” or “Mary lied to Bob.” Without the grammar, it would be impossible or at least very hard to know what people were saying.

Displacement means we can communicate ideas that are not in our immediate environment or that exist only in our imaginations. We can express ideas that haven’t yet happened and that might never happen. We can speak of things as they might be, should be, or could be. Displacement allows us to create stories of journeying to the center of the earth or traveling back in time to a galaxy far, far away. Neuroscientist Dean Buonomano, the author of Your Brain is a Time Machine, says that this ability to create the past and future makes “Homo sapiens, sapiens, it makes Homo sapiens wise.” Displacement also allows humans to do something we excel at, prevaricate, which is a fancy word for lie. Lies are after all hypothetical scenarios that exist only in our imaginations. And finally, displacement allows us to feel that most human of feelings, regret. Regret is about traveling mentally to the past, rewriting it, and traveling forward again to see what might have been. Daniel Pink in The Power of Regret goes as far as to say regret is what makes us human.

Another important aspect of language is that it is context-specific. Very often when you hear a sentence in isolation, it can be very ambiguous. We see this problem all the time when people are quoted “out-of-context” in the news. To illustrate, here are two actual sentences my son uttered this summer:

They beat the junior coaches with the orangutan.

My crocodile got diamonds, so there was a disco party.

The first sentence makes sense only if you know that the “orangutan” is a chess opening. The second only makes sense if you know something about the video game Disco Zoo (which I do not). Context, or the lack thereof, is also why headlines are sometimes so funny. Human language, as it turns out, is more complex than stringing together a series of words in the right order using the correct rules. Communicating effectively requires knowing something about the cultural context in which it is embedded.

Language is Context-Specific

Animal Call Systems

It is informative to compare how non-human animals communicate with how humans communicate. How much of what we do with language is unique to us? We know that all animals communicate and even plants communicate with chemicals, which ecologist Suzanne Simard (2016) calls a kind of intelligence. Some forms of communication are passive like the false eyes on the wings of a butterfly that make predators think twice before approaching. Other communication systems involve a signal. Ants, for instance, use chemical signals to communicate with each other. Still, other animal communication systems use sound produced from a vocal tract. These are referred to as call systems and include a repertoire of specific sounds, such as hoots, panting sounds, and grunts.

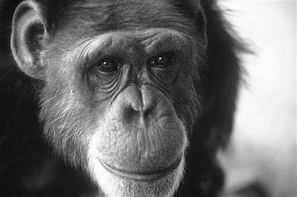

We know mammals, birds, and fish species share the gene FOXP2 with humans, the only gene yet known to affect language. The FOXP2 genes of these animals also influence communication. When FOXP2 is deleted in infant mice, they cannot make the certain vocalizations needed to communicate with their mothers (Shu et al. 2005). Animal FOXP2 genes, however, take a slightly different form than the human gene. In chimps, for example, there are only two changes in the FOXP2 protein, but those changes seem to add up to big differences. FOXP2 is the only gene we know of that influences language, but it is assumed there are many more yet to be discovered.

Are animal calls completely automatic like inadvertently screaming during a scary movie or yelping after stepping on a lego? Michael Wilson, who studies chimpanzee vocalizations, writes, “Like humans, chimpanzees scream when they are being chased, beaten, or otherwise attacked or threatened. These screams often sound disquietingly similar to human screams.” Primatologist Jane Goodall, who lived for years among the chimpanzees at Gombe National Park in Tanzania, records an instance of a chimpanzee who found a cache of bananas and wished to keep them for himself. He was unable to suppress the excited rough grunt call that signals the discovery of food and attempted as best he could to muffle the call by placing his hand over his mouth. The reverse seems to be generally true as well. Goodall (1986:125) writes, “The production of sound in the absence of the appropriate emotional state seems to be an almost impossible task for a chimpanzee.” Chimpanzee vocalizations then seem strongly tied to emotion.

Yet there are interesting exceptions. Goodall notes that chimpanzees will suppress calls while patrolling their territory. Recent evidence also suggests that chimpanzees communicate intentionally. In one study researchers placed a fake snake along a chimpanzee path. Chimps were more likely to make a call when their companion chimp had not already seen the snake (Schwartz 2017). It could be that chimp vocalizations are both automatic and under voluntary control in different situations, not so different from humans.

A Little Bit Like a Word

One of the most interesting cases of primate vocalization comes not from chimpanzees, but monkeys. Vervet monkeys of east Africa have specific calls for specific predators, specifically leopards, eagles, and snakes. When a monkey hears the alarm call for leopard, he climbs a tree. When he hears a signal for eagle, he finds cover. For the snake alarm, he rises and looks around for the predator. Robert Seyfarth (2014) points out that the calls are something like a word, a sound that represents something. The monkeys aren’t automatically responding to the sight of a predator, but to the call itself. Monkeys also don’t automatically respond to calls and can become habituated to a repeated call over time to the point where the call is ignored (Schwartz 2017). Other monkeys and even ring-tailed lemurs have similar systems. One thing the vervets are unable to do, however, is to combine the calls for snake and eagle into a new, imagined creature, like “sneagle”. They also can’t chat about leopards or reminisce about the day that Larry almost got picked off by an eagle. So, productivity and displacement don’t seem to be present.

Cultural Transmission

Some animals, like humans, learn the language of their environment. Some sparrow calls are both hard-wired and learned. If a fledgling sparrow is removed from its local environment, it will learn only a simple version of the local sparrow song. But there is another more elaborate version of the song that adults sparrows sing, “remixed” on top of the generic song. The fledgling has a 50-day window to learn the detailed song or it never will. This demonstrates that elaborated sparrow song is transmitted through learning or cultural transmission, but the generic song is innate or hard-wired.

In another case, monkeys appear to be multilingual, learning the alarm calls of several other monkeys. Primatologist Klaus Zuberbuehler studies West African monkeys, who can translate each other’s calls. Zuberbueler tells a story where he is walking back to camp after a long day of studying monkeys and he hears a monkey troop sound off a chorus of leopard alarm calls. He walks on and hears more leopard alarm calls, and then still more. Slowly, it dawns on him. The leopard is not tracking monkeys, it’s tracking him. Later, relieved at not being eaten by the leopard, Zuberbueler realized he wasn’t a human outsider studying the monkey communication—he had become just another multilingual primate.

Displacement

Most animal call systems in the wild lack displacement. One example of animal displacement comes from the insect world. A honey bee has about 1 million neurons in its brain compared to the human 80 billion (give or take). Despite this vast difference, they can signal the existence and location of nectar situated some distance away from the hive through a waggle dance. The bee moves in a figure-eight motion, which conveys the distance and direction of the food source. Bees even take into account the movement of the sun as they dance. Importantly though, the honey bee has to see the food source to perform the dance. There are a few instances of monkeys deceiving other primates with calls. The capuchin monkey may give the alarm call for a predator when there is no predator, thereby distracting other monkeys from food. In the wild, however, animals don’t appear to talk about things they have never seen before, as do humans.

Productivity and Grammar

Recently, there has been some indication that other non-human animals have some capacity for productivity, or a little grammar, in their call systems. Work with Cambell’s monkeys reveals that they combine two sounds to create new meanings like “not urgent”.

Ape Language Projects

It is clear that non-human animal communication in the wild has some things in common with human language, but productivity, displacement, and grammar are not found to the same degree in animal communication as they are in humans. Early in the 1900s, psychologists began to wonder though whether apes in captivity would behave like humans given the right kind of environment. A husband and wife team, the Kelloggs, decided to raise an infant chimp named Gua alongside their infant son, Donald. Gua was raised and socialized as a human child, immersed in language. Because chimpanzees developed faster than humans, Gua was meeting her developmental milestones earlier than Donald. She was far more mobile than Donald and feeding herself competently. Gua could respond to language but was not producing language. Quite the contrary, instead of Gua learning to speak, Donald allegedly began to “pant-hoot” like a chimpanzee at which point, the Kelloggs decided to end the study.

A second attempt was made by another couple, the Hayes, in the 1950s with a chimpanzee named Viki. It was thought that Viki might be able to learn spoken language (English) through behaviorist principles. Behaviorism stressed the idea of learning through a system of rewards and punishments. It was thought that language was no different. Viki underwent a behaviorist program, receiving rewards for producing the correct sounds of English. Because she had trouble enunciating, her mouth was manipulated into the correct shape. Viki, however, only produced the words: mama, papa, up, and cup, and even those were not distinct.

What is now clear is that these studies were doomed to failure from the start. Without even considering the brain, the morphology, the form, of the human vocal tract (the larynx, pharynx, mouth, and nose) differs from that of other primates. The larynx, also known as the voice box, is situated lower down in the throat in humans than in other primates. The larynx houses the vocal cords. Air from the lungs is pushed through the vocal cords (flaps of tissue that vibrate), through the pharynx, and on into the mouth where most sounds of language are shaped. In chimpanzees, the larynx is higher up the vocal tract such that most of the air is pushed through the nose, making it difficult for chimpanzees to enunciate the sounds of language. A problem that the human configuration presents is that a descended larynx means that there is a shared pathway for both air and food/water, meaning that speaking and eating in close proximity is a problem. In short, the ability to articulate many different sounds is a choking hazard. Human infants are born with a high larynx, allowing them to breathe and drink in close proximity. The larynx then begins to descend around three months of age.

Apes and Sign Language

In 1966, Washoe the chimpanzee was the first non-human to learn signs in American Sign Language (ASL). She was raised by the Gardners, a psychologist couple. Washoe learned about 350 words of ASL and could combine up to five words. She used signs to refer to categories of things; the sign for “dog” was used for any dog and not just a specific dog. At first, Washoe was rewarded with tickling, but later this was suspended because it was interfering with the goal of conversational language. Washoe showed some ability to produce features of human language, namely productivity, displacement, and cultural transmission.

Productivity: “Waterbird”; Drinkfruit

Displacement: Washoe could refer to objects not present.

Cultural Transmission: Washoe taught some signs to other chimps.

Because chimpanzees are very strong, five times as strong as an adult human male, and can be potentially aggressive, one researcher turned to another, less volatile, primate, the gorilla. Graduate student Penny Patterson was loaned Koko, a female western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla) from the San Francisco zoo to be studied in an ape sign language project. Koko excelled at ASL, learning anywhere from 400 to 800 signs. It is claimed that Koko also produced her own signs, which Patterson called Gorilla Sign Language or GSL. Koko is reported to have had conversations with Patterson, a startling claim since in other projects apes only ever made requests in ASL. Here is one reported conversation:

KOKO: That me (pointing to a picture of a bird).

RESEARCHER: Is that really you?

KOKO: Koko good bird.

RESEARCHER: I thought you were really a gorilla.

KOKO: Koko bird.

RESEARCHER: Can you fly?

KOKO: Good.

RESEARCHER: Show me.

KOKO: Fake bird, clown.

RESEARCHER: You’re teasing me. What are you really?

KOKO: (after a few minutes) Gorilla Koko.

In this case, Koko appears to use linguistic displacement, talking about herself as a flying bird, which can only occur in her imagination. Here is another example of an alleged conversation:

PENNY (researcher): What did you do to Penny? (three days ago)

KOKO: Bite.

PENNY: You admit it?

KOKO: Sorry bite scratch. Wrong bite.

PENNY: Why bite?

KOKO: Because mad.

PENNY: Why mad?

KOKO: Don’t know.

In this case, Koko appears to be talking about something that happened in the past, which would qualify as temporal (time) displacement. Also, the question arises of whether Koko understands the morality of unprovoked biting, or perhaps Koko is protesting her captivity and can’t quite analyze her emotions.

Another approach to teaching apes language are lexigrams. Lexigrams are symbols that represent different things in the captive ape’s environment. Most lexigrams are arbitrary with respect to what they represent so that the lexigrams are more like human language than some ASL signs. Sign language has many signs that are not arbitrary, such that the sign for drink resembles the act of drinking. Sarah, a bonobo chimpanzee (Pan paniscus), was being taught to use lexigrams with minimal success. Her adoptive son Kanzi was there during the sessions. Researcher Sue Savage-Rumbaugh reports that Kanzi, who had not been formally taught, began to use the symbols spontaneously. This is an important difference between Kanzi’s communication and the apes taught to sign. Koko and Washoe had learned to use signs through a system of rewards. Kanzi’s communication was spontaneous, more like how human children spontaneously acquire language.

Kanzi’s understanding of English, his receptive language, exceeds his ability to produce it, not unlike young children. He can understand simple requests and acts on them accordingly, even if the request is strange. For example, if the researcher asks Kanzi to “put the shoe in the refrigerator,” Kanzi will often do so. This suggests to the researchers that Kanzi might understand simple sentence structure or grammar. More complex statements like “Put the umbrella, but not the banana under the chair” are more difficult for Kanzi. In one test of language comprehension, Kanzi performed slightly better than a two-year-old child (Kanzi: 76%; Child: 66%).

Critiques of the Ape Language Projects

When the ape sign and lexigram projects began there was a great sense of optimism that apes would be able to communicate all sorts of inner thoughts that humans previously had no access to. This would have profound implications for who apes are, who humans are, and how we view and treat apes and non-human animals in general.

One project, however, decimated the field of ape language projects. Psychologist Herbert Terrace obtained a juvenile chimpanzee he named Nim Chimpsky to start up an ape language project. Nim learned many signs in ASL and appeared to be a huge success. Unlike the Washoe and Koko projects, Nim’s sentences were examined systematically and quantitatively. It was found that Nim’s success was limited to using signs he had imitated. There was no evidence for productivity, and he never combined signs into new sentences or words. Nim never learned to sign spontaneously without a reward, and Nim’s sentence structure was random. So, while Nim was able to use signs to make requests, grammar, that cornerstone of human language, escaped him. Criticisms of the Nim Project were that he was often isolated in a cage and lacked a nurturing environment, which could explain his inability to master grammar.

It is clear that apes are using signs to make requests of humans. In that regard, apes, and humans are communicating. But, of course, we do this with our canine pets as well. Dogs understand that the word “walk” will likely result in going outside. But whether apes know the meaning of the sign is still unclear. The criticism lodged against the ape sign projects by psychologist Steven Pinker and linguist Noam Chomsky is that apes were conditioned to know that certain signs produce results, but don’t understand the underlying meaning of sentences. Apes can predict because they are highly intelligent creatures, that signs for “more treat” or “treat more” will result in a treat. This is called conditioned response. In effect, Pinker and Chomsky think the apes are performing clever tricks rather than using language.

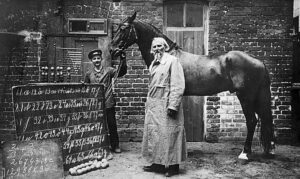

Another criticism is that the researchers were subconsciously prompting the animals to respond. This is called the Clever Hans Effect. Clever Hans was a horse that “could do math”. His trainer Wilhelm von Osten would present Hans with a math problem, then Hans would stamp out the correct answer with his hoof. It was later revealed that Hans was picking up on subtle, and maybe even subconscious cues of his trainer. When Hans was nearing the correct answer, people would give off subtle cues and Hans would stop stamping. While Hans couldn’t do math, he was remarkable at reading emotional cues. Critics say apes are giving the trainers what they want to hear based on reading on emotional cues.

A third critique of the ape language projects is called cherry picking. Cherry picking means selecting the evidence that confirms your hypothesis while ignoring results that do not. For example, communication that seems like conversation, productivity, or displacement is documented, but conflicting results are discarded as not relevant or accidental. The results of Koko’s language progress are entirely anecdotes or stories. We don’t have the full range of Koko’s utterances, and significant data has not been reported—the quantitative data. With data, or videos of Koko’s language production, we can evaluate what Koko’s responses were really like on the whole. Some conversations with Koko seem convincing, others less so. Critic Jane Hu (2014) described a live AOL chat between Koko and the public, where Koko responds to the question, “What’s the name of your cat” with “Foot”. We could ask, for example, how often did Koko respond inappropriately versus appropriately given the context?

Most of these ape language projects happened in the 1960s and 70s. Sadly, Koko recently died in 2018. The only project still going involves Kanzi, now in his 30s, whose results have been the most systematically studied. The foundations that started these studies, however, (Gorilla Foundation and Great Ape Trust) were marked by employee resignations, accusations of mismanagement, and endangering the animals.

Though there is still debate around the subject of ape language, many people agree that animals have some building blocks of language, some capacity for productivity, displacement, and grammar, but none use these to the extent that humans do. This is not to say that humans are therefore better than apes, but that we simply have a different communication system, which is not too surprising since we are, after all, different species. Whatever their linguistic abilities, whether they truly understand the meaning of words or are conditioned by rewards, Washoe, Koko, and Kanzi are truly remarkable and intelligent creatures.

Storytelling

Author Terry Pratchett writes in Witches Abroad, “People think that stories are shaped by people. In fact, it’s the other way around.” What does he mean by this? Don’t people create stories? Of course, they do, but stories also have great power in shaping how we think and see the world. Jonathan Gottschall makes the argument that storytelling is what humans do best and is a talent unique to us. Homo fictus, he suggests, is as good a descriptor of our species as is Homo sapiens. Students often remember a story more so than say a definition or a lengthy explanation. Who remembers the story of Jack the Baboon who ran the railroad switches? Who remembers the definition of tool? Chances are Jack sticks out more in your memory than, “an object used to alter the condition or position of another object.” Gottschall says that storytelling is automatic for humans. When people were shown shapes moving around a screen, most saw more than just geometry, but a drama unfolding. Our minds, Gottschall argues, are made for telling stories, and they are how we make sense of the world around us. We impose the structure of stories on our everyday experience, using our imaginations to create our world. We are immersed in stories—action adventures, jokes, romance, comedies, dances and holy stories—which bring order to our world. Music and photos also tell stories. For instance, my friend recently posted this photo entitled, “A Short Story about Decisions.”

We are swimming in stories that revolve around our values and identity—stories of our history, ancestors, human triumph, and outrage. Gottschall points out that even in our sleep, we don’t escape storyland. Stories shape our experiences and create and transmit culture. In the United States, our sacred values, stories, our identities, and symbols are contested and debated daily on social media. Consider these issues, the values they represent, and the stories that support or negate them: Whether the government should limit semi-automatic weapons, whether health care is a human right, how DACA recipients, asylum seekers, and refugees should be treated, what bathroom transgender people should use, and whether people can “take a knee” at sporting events. Our values are constantly being reformulated, and new stories and symbols are created to support those values.

In Hogfather Terry Pratchett writes, “Humans need fantasy to be human. To be the place where the falling angel meets the rising ape.” When we read books, we can magically become immersed in a different world, to the point where we can forget where we are. We fill in the details with our imaginations—the furniture in a room, the layout of a house, or the expression on a character’s face, building the story alongside the author. Indeed, brain scans indicate that we experience stories not passively, but actively, as if we are actually experiencing what the character is experiencing. In this light, stories are a powerful way to transmit culture, by allowing the viewer to experience the character’s feelings. Performance mentors like Todd Herman know the power of a good character and a good story in improving performance. Herman advises his clients to create an alter ego with a back story such that when the going gets tough, one simply embodies the alter ego and their backstory to give them confidence and courage. Beyoncé famously created her alter ego Sasha Fierce to be able to perform aggressively and sensually when she needs to. As Beyoncé explains, “I have someone else that takes over when it’s time for me to work and when I’m onstage, this alter ego that I’ve created kind of protects me and who I really am” (MacInnes 2008). Other famous people have adopted different personae to embody a character. Dr. Martin Luther King, for example, wore eyeglasses even though he didn’t need them. And Winston Churchill had a collection of hats for when he needed to embody different characters.

Every culture has its own stories that reflect and reinforce the values of that society, and often these stories are reiterated during rituals. Americans have had national stories of George Washington chopping down his father’s cherry tree, Pilgrims and natives feasting together peacefully, and Columbus “discovering America”. These stories aren’t just entertainment, but a way to promote certain values and visions. And of course, these stories, or myths, can change over time as the values of a society changes. Today many recognize Indigenous Peoples day, for example, rather than Columbus Day on October 8. Stories are not just backdrops or reflections of culture, they can shape culture as well. Gottschall points out that the television program Will & Grace had the effect of changing American minds about same-sex relationships—the “Will & Grace Effect.”

Author Chimamanda Adichie cautions that “single stories” create narrow and simplistic ideas of other people and their experiences. When we are exposed to a multitude of stories from other walks of life or different cultures, we allow ourselves to see, and maybe even feel, the perspective of others and widen our own worldview. There is fear that social media, especially Facebook, serves up only those stories which reinforce the user’s worldview. These streams of single stories could lead to a kind of fossilization of thinking, an “us and them” mentality, and an inability to see another’s point of view. Restricting books, burning them, or preventing certain groups of people from accessing them allows for only a single story. Activist and author Malala Yousafzai was shot by the Taliban for simply wanting an education, and for seeking out other stories about what girls and women could be. Anthropology is all about recognizing that there are many stories about what humans can be.

Language and Thought

What people say affects the thought of other people. If this weren’t the case then advertising wouldn’t work, teaching wouldn’t work, and culture itself would not work. But there is another idea, that the structure of language—the categorization it uses, the sentence construction, tenses, and how it refers to gender—affects how people think. This idea is called the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis. The strong version of Sapir-Whorf suggests that one cannot think outside one’s language, or that language is thought itself. In this model, language is a kind of mental trap that you can’t escape. It is pretty clear that this is not the case, because language-less babies can learn a native language. People can also learn and understand foreign words that don’t occur in their native language. For example, English speakers do not have an equivalent word for Weltanschauung, which in German means delight over someone else’s misfortune. Even though there is no equivalent word in English, the meaning of the word is immediately grasped. Likewise is Backfeifengesicht, a face in need of a punch. Another example in Swedish is mångata, which means moonlight reflected on water.

The weak form of Sapir-Whorf, however, subscribes to the idea that the structure of language shapes the way you think, or at least forces you to pay attention to certain things. A visual analogy to this is a study that asked participants were asked to watch a video and count how many times a basketball was passed between players. Participants in the study focused so keenly on the passing of the basketball that they missed a person in a gorilla suit who wandered through the scene. Linguist Lera Boroditsky points out that humans can’t pay attention to everything, and so we carve up our world into manageable categories using language. Linguistic structures and categories, she argues, can influence how we perceive space, time, color, events, and quantities. According to Boroditsky, how we carve up the world says a lot about who we are, and each language represents a different way of thinking.

Boroditsky, for example, points out that some Australian aboriginal cultures use cardinal directions—north, south, east, and west—to refer to small-scale situations. You could say that there is a honey ant on your southwest toe, for instance. In this case, language forces one to think about where they are in space at all times. The Pirahã of Brazil also do not have words for their left and right hands (Everett 2009). Daniel Everett who spend years with the Pirahã recounts a conversation with a Pirahã man (Everett 2009):

Everett: Okay, this hand is the one that Americans call the left hand….What do the Pirahãs call it?

Pirahã man: Hand. (in Pirahã)

Everett: Yes, I know that it is a hand, but how do you say “left hand?”

Pirahã man: Your hand. (in Pirahã)

Everett: No. Look. Here is your left hand. Here is your right hand. Here is my left hand. Here is my right hand. How do you say that?

Pirahã man: This is my hand. That is your hand. This is my other hand. That is your other hand. (in Pirahã)

When Everett tried again after a break, the Pirahã man replied with, “The hand is upriver,” and “The hand is downriver.” Everett gave up. A week later Everett went hunting with some Pirahã men. When they shouted, “Turn upriver,” the man turned right. That is when he realized that the men were giving directions using the river, invisible to Everett, as a landmark. Unlike the Kuuk Thayore, Pirahã oriented themselves to the river as opposed to cardinal directions. When the Pirahã entered a new town the first question they asked was “Where was the river?” because it was critical to orient themselves in space and give directions.

In other cases, people carve up the color spectrum in different ways, sometimes having no category for a particular color. W.H. Rivers found that natives of the Torres Straits had definite words for white, black, and red, but had no distinct word for blue, often using “black” to describe it. There does appear to be a dimension of color words that is not cultural, but deeply embedded in the human mind, as everyone has color names for “dark” and “light”. And, if a language has only three color terms, it is almost always “dark”, light”, and “red”. People with no specific terms for numbers, like the Pirahã of Brazil, aren’t able to keep track of exact quantities. Yet, they remember a huge number of terms for plants and animals. The Pirahã also have to indicate how they came about information or evidence, whether it was heard, seen, or deduced. English speakers don’t have to indicate how they got their information. When Daniel Everett tried to teach the Pirahã his religion, he was put in an awkward position because he was unable to verify his beliefs to the satisfaction of the Pirahã.

Boroditsky also points out that some languages force one to consider where the information came from. The way we phrase things reflects mental concepts on things like time. Every language the metaphor of space to talk about time, just not all in the same way (Spinney 2005). In English we say “back in time” or “the past is behind us” or “I look forward to hearing from you”. Or we can say the meeting has been moved up two days or moved forward two days, which might be very confusing for a non-native speaker of English. In other languages like Aymara, the past is in front because it has already been seen or experienced. The unseen future is behind. Boroditsky explains, “I think what’s important about this is that linguistic diversity is a real testament to the ingenuity of the human mind. That our minds have the exquisite capacity to create not one pass at the physical universe that we’re all trying to describe, but seven thousand different passes. There’s not one linguistic universe, there are seven thousand universes.”

We can similar similar ideas out side of language. Certain activities force us to focus on certain things to the exclusion of other things. Kids playing video games really don’t hear their parents yelling for them because their attention is diverted elsewhere. This is a well-known phenomenon called the Spotlight Theory of Attention. Human attention is like a spotlight where it can only focus on a certain amount of information at any one given time and everything else is ignored. The effect is so pronounced that burn victims play a video game Snow World during procedures like wound dressing to divert their attention away from the pain. Snow World players reported lower incidences of pain and fMRIs showed reduced blood flow in pain regions of the brain. We can see how language can force a person to focus on certain information to the inclusion of other information, and be less aware of factors not required for communication. Patients run out of “cognitive resources” to focus on the pain (McGonigal 2015). In a sense, language is like Snow World, diverting our limited cognitive resources toward what is required of speakers.

Other linguists, like John McWhorter, author of The Language Hoax, acknowledge that language structure shapes thought a bit, but he doesn’t think it amounts to an entire worldview. McWhorter thinks that slightly different conceptions of color, time, or space are interesting, but they are the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the worldview of an entire culture. One CNM student who also happened to be a firefighter pointed out that firefighters think of structures in terms of the front entrance of the structure, which is labeled “alpha”. The sides going clockwise are labeled “beta, charlie, and delta”. McWhorter might argue that this is interesting, but isn’t tantamount to a worldview. Learning a second language he argues, is useful because you can connect with speakers and learn about how they see the world from what they say, and less so by the structure of their language.

Language Change and Language Shift

Languages, like species, are changing constantly. When students in English literature are confronted with Shakespeare, Chaucer, or Beowulf, they are often at a loss to comprehend Old English, Middle English, or even Shakespeare’s modern English. It can even be difficult for parents to understand their own children. My son, for example, used a word in a way I had never heard of before when he said, “You are soooo budget Mom.” He has also accused me of being a “noob”, a computer novice, on several occasions. Neologism or new words, like vlog, noob, and tweet reflect our increasing use of technology and the Internet. Often people feel that language, perhaps along with morality in general, is deteriorating. This perspective is a prescriptivist one, the idea that there are right and wrong ways of speaking or writing. Many linguists, however, tend to see language as simply changing to suit new situations. These linguists are more descriptivist, being interested in how and why language changes over time. Of course, features like politeness and some conventions are writing are often needed because they allow us to communicate both respectfully and easily.

Perhaps no other form of linguistic change has gotten so much grief as texting. For some, texting heralds the end of civilization itself. McWhorter tends to take a more nuanced approach to texting, describing it simply as “fingered speech.” He says that texting is a different writing system that reflects the rhythms of spoken language rather than written language. “Lols”, McWhorter argues, don’t mean you are actually laughing, but rather represent an empathy marker, a way to show the person that you’re connecting with them emotionally. These texting conventions fill in for the expressions and head nods that normally accompany spoken conversations.

Though language is constantly renewing and replenishing itself, language shift, giving up one’s native language for a more dominant one, is increasing. Half the world’s population speaks just 50 of the 7,000 languages, and the remainder of the world’s population speak the other 6,950. Those languages, spoken by relatively few speakers are in danger of being lost forever at a rapid rate. We can think of this trend as being related to the Anthropocene because those areas in great environmental jeopardy are also places of great linguistic diversity. These “hotspots” of biological diversity contain 70 percent—more than 3,000— of the world’s languages. As people can no longer sustain a living on their traditional lands as a result of logging, intensive agriculture/ranching, mining, oil drilling, and so on, they become displaced. And consequently, they also tend to give up their traditional life-ways, including their language. As Barry Mosses explains, economics is often at the heart of language loss.” In other cases, there are movements to actively disassociate a people from their language, often punishing children for speaking their native tongues. An estimated 50 to 90 percent of the world’s languages will be gone by the end of the century.

There is some cause for hope though. The link between biodiversity and linguistic diversity may usher in a new kind of approach to both conservation of species and cultures. As Larry Gorenflo explains, “It provides a wonderful opportunity to integrate conservation efforts—you can have people who can get funding for biological conservation, and they can collaborate with people who can get funding for linguistic or cultural conservation” (Kinver 2012). Linking of science, conservation, and culture has paid off in other arenas like the Cofán people of Ecuador, who work to preserve the environment, and engage in scientific studies while maintaining their cultural heritage.

Languages, like species, can be critically endangered. What matters most is not sheer numbers, but young people. When languages are no longer being taught to children, then there is little basis for passing on the language, and they soon become endangered or go extinct. And if language indeed influences thought, then we also lose ways of perceiving the world as well as stories that encapsulate the beauty and human genius of these cultures.