The speaker is the bridge between the poem’s experience and the reader. Like language, when voice works best, it becomes invisible, cemented to, part and parcel of the poem’s experience. Tone of voice is responsible for creating trust between the reader and the speaker, and in enticing readers to lose themselves in the experience; it is responsible for letting a reader be enraptured by the poem.

In the introduction to the 2006 Best American Poetry anthology, the judge for that year, poet Billy Collins, explains the key role that a poem’s tone of voice played in determining which poems to place in the pile that left him “cold” and which poems to place in the pile that caught him “in their spell,” those that he would eventually consider for inclusion in the collection. Collins begins by elucidating how the voice of a poem took on a bigger role once Modern poetry began to experiment with free verse:

Once Walt Whitman demonstrated that poetry in English could get along without standard meter and end-rhyme, poetry began to lose that familiar gait and musical jauntiness that listeners and readers had come to identify with it. But poetry also lost something more: a trust system that had bound poet and reader together through the reliable recurrence of similar sounds and a steady dependable beat. Whatever emotional or intellectual demands a poem placed on the reader, at least the reader could put trust in the poet’s implicit promise to keep up a tempo and maintain a sound pattern. It is the same promise that is made to the listeners of popular songs. What has come to replace that system of trust, if anything? However vague a substitute, the answer is probably tone of voice. As a reader, I come to trust or distrust the authority of the poem after reading just a few lines. Do I hear a voice that’s making reasonable claims for itself—usually a first-person voice speaking fallibly but honestly—or does the poem begin with a grandiose pronouncement, a riddle, or an intimate confession foisted on me by a stranger? Tone may be the most elusive aspect of written language, but our ears instantly recognize words that sound authentic and words that ring false. The character of the speaker’s voice played an indescribable but essential role in the making of those two piles I mentioned, one much taller than the other.

It is interesting that Collins refers negatively to the “voice of a stranger,” as aren’t all speakers of poems strangers to a reader? We do not know the poet, so how can we possibly know the speaker? Yet here, Collins suggests that there is something in us that does know something of the speaker, some credibility that “sounds authentic” rather than “ringing false,” and this has more to do with tone of voice than subject matter. After all, who believes someone who doesn’t sound trustworthy? It is like watching a play with bad acting—you can’t lose yourself in the story or character, you cannot transport, you cannot release yourself to get “caught in its spell.” We have trouble trusting our senses and giving our time to the speaker without suspicion, which acts as a barrier between the reader and the experience. It is similar to what poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge called a “suspension of disbelief,” in a sense: We need to be willing to be wrapped up in a poem’s experience, and if we’re untrusting then we’re not willing. Tone of voice develops from the many moves a poem makes and can be considered, in another way, the stance the speaker takes, the relationship between the subject matter and the speaker.

Trust vs. Truth

How do we gain someone’s trust? We can build a reputation if we’re, say, a journalist or reporter. We can create a history of trust with a friend or spouse. We can plead and swear on a Bible like we do in courtrooms, but even then there’s no guarantee someone is telling the truth. Maybe you remember from your childhood or teenage years what you needed to do to be believed even if you were fibbing. Much of it had to do with details. The more specific the details of a story, the more convincing the story. If we look at film and television, we see entire narratives based on deceit and maintaining a lie. The AMC hit series Breaking Bad followed the life of Walter White who had to constantly work to keep his family from discovering that he was involved in the world of crystal meth. In the 1998 film Shakespeare in Love, Gwyneth Paltrow’s character dresses as “Thomas Kent” in order to audition for a performance in which women are prohibited to perform. And in Ferris Beuller’s Day Off (1986), Ferris has to deceive his family and teachers in order to keep from being caught for skipping school—after deceiving his mom by convincing her he was too sick to go to school.

Alternatively, in the 1979 Monty Python classic The Life of Brian, poor Brian Cohen, born on the same day as Jesus, cannot convince anyone he is not God’s only holy son. We can ask how these characters convince other characters (or not) of their stories, but the real question in regard to creative writing is more along the lines of: why are we the audience so lost in these characters’ lives and swept up in their stories? And how can we, as the speaker of a poem, make our audience feel with that same intensity when they read our poems?

Like the stories in these movies, poems do not have to be factual or even based on fact to earn the trust of a reader and ring true. The experience poems create can be either real or entirely made-up. The speaker must simply, as Billy Collins says, “sound authentic.” The truth of a poem, like the truth in a short story or novel, need not be based on the author’s experience; it need simply be an experience that convinces us to lose ourselves in it and the voice that tells it.

Don’t Try to Sound Poetic

One of the mistakes I see beginning writers make frequently is using archaic or unnatural diction, or word choice, in a poem. Words like amongst, thou, thine, hath, thee, thyself, or adding an –eth to a verb: stoppeth, handeth, etc. Archaic words like these standeth out as thy sore thumb. They are of a different time and generation. When we use them it feels to the reader as though we are putting on a cloak, disguising ourselves, creating a voice that is untrustworthy—again, not because the story may not be true, but because it sounds like the speaker isn’t real. When we write, whether we write as ourselves or as someone we are pretending to be—like acting— we must sound like a real person.

Some of the thinking that is behind the use of archaic diction is that we feel that we need to sound poetic, so we use words that we are used to thinking of as being poetic. But the truth is that the reader comes to the poem wanting to be surprised by new uses of language, its music, its imagery, wanting to connect to a real speaker.

Pick up a literary journal or book of poems today and you will find poems that are conversational, friendly, confessional, reflective, meditative, or serious, but what they all contain is a speaker who is knowable, or as Collins explains, authentic. Of course, there are many schools and styles of poetry. Language poetry, for instance, isn’t interested in a speaker’s voice or expression, but rather places more of an emphasis on the reader’s interpretation of how language is creating meaning in and of itself. A reference guide to schools of poetry can be found at The Poetry Foundation’s web site.

Balance Sentimentality and Emotional Risk

Without emotional risk, a poem can lack tension, energy, and lose the chance of producing insight. If a speaker isn’t risking something in a poem, then why is it being written? It’s like getting into a car and driving nowhere. The poem is the vehicle we climb into as a reader and we want the driver to take us somewhere. Whenever we express ourselves and share our feelings, just as whenever we hop into a car and drive, we take a risk.

William Wordsworth referred to a poem as “a spontaneous overflow of emotions…reflected upon in tranquility.” His definition suggests that a poem contains two possible sources of tension: one triggered by the poetic event (either real or imagined) that caused a surge in sensual and emotional intensity almost like a chemical reaction; and a second source (either real or imagined) that transpires when the speaker applies reflection, thought, or ideas to the first event and the reaction. The second part takes place after time distances an intellectual perspective from a frenzy of emotions. There is what we can call the first occasion for the poem—the event and the instantaneous reaction of the body—and then the second occasion: the speaker’s reflection which aims to make meaning of it all. In the first part, tension is caused by what could be considered a chemical reaction between the event and the speaker’s reaction; and in the second part it is a speaker’s thoughts, ideas, reflections which can cause tension. At one of these two points of entry, there must be some form of duality or complexity. If the poem arises from the first part, the poem will tend to be dramatic or narrative and focused on the sequence of events. If the poem arises from the second part of the equation, the poem will tend to be meditational or lyric, focused on the poet’s thoughts, perceptions, and feelings. Either way, the poem must still contain concrete, detailed images which anchor the sentiment of the speaker to an event, for if there isn’t the anchor, the poet risks drifting off into a world of over-sentimentality.

Beginning writers, attempting to instill intensity in a poem, often lapse into over-sentimentality, exaggerated or overly dramatic emotions without just cause for them. As Oscar Wilde wrote, “A sentimentalist is one who desires to have the luxury of an emotion without paying for it.” Over-sentimentality results in sappy, clichéd writing, and an inauthentic voice. Sentiment, a speaker’s emotional state, is not the same thing as over-sentimentality. All speakers have some sort of emotional stance, or sentiment, in a poem—in fact, sentiment is required to produce a knowable speaker to whom a reader can relate. And this sentiment—this abstraction we as readers will be made to feel—must arise from the concrete particulars that justify the level of emotion produced.

In the following examples, the text falls victim to over-sentimentality:

- When I found out about Charlie’s new girlfriend, it felt like my heart exploded into a billion pieces. I cried so much I thought my tears would drown me. I would never love again.

- The poor, innocent, homeless boy tugged at my skirt. It wasn’t his fault he had no shelter, but the cruel winter and its roaring wind didn’t care about the fragile boy’s body or soul. It howled like a demonic coyote about to devour a frail fawn smelling delicate flowers for the first time.

Many times oversentimentality results from a focus on telling rather than showing, as is the case with the first example which tells us what the speaker was feeling rather than show us through actions or descriptions. The image of the heart bursting into a billion pieces is cliché and is used in place of a fresh image. The word “never” is extreme and unbelievable. In fact, when we write we want to avoid words with ultimatums as such—final, never, always, all, none. Usually they are simply not true and difficult to imagine.

In the second example, the writer uses extensive images to play on the reader’s emotions. Note the use of adjectives—small, innocent, cruel, poor, demonic, fragile, delicate. Remember that adjectives tell instead of show. The example is so over the top that as readers we begin to feel emotionally bullied by the writer.

So, what to do? You cannot have a poem dodge sentimentality entirely; otherwise, your speaker will be robotic. But, one must be careful not to indulge in extremities and exaggeration either. There is a balance between the solipsistic rant, complaint, or laud, and the raw, sarcastic, angry expression: for example, “Go fuck yourself with your atom bomb” (Ginsberg); “Boy, do I love America” (Dockins); “I hate them as I hate sex” (Gluck). It’s all about balance and anchoring the sentiment in concrete images and daring to expose a speaker or character’s vulnerability, their humanity.

Use Contrasts

To balance over-sentimentality and emotional risk, take a cue from fiction technique and try to work in contrasts to maintain balance. If a character is a mean, selfish person, try to find or invent an occasion in their life when they were vulnerable. If a character is generous and giving, try to find or invent a time when they weren’t. The contrasts will add tension and complication and make the character or speaker seem more human. You can see this contrasting and complicating approach made successful in film, television, and fiction where sometimes the main character may be despicable, but we readers or viewers can’t help but feel pity, empathy, or some sort of hope for him or her. In Breaking Bad, Walter White is a selfish liar whose drug making causes the deaths of numerous people. Yet when we see him hold his newborn, share a touching moment with his disabled son, undergo chemotherapy, or express over and over his reason for making meth—to support his family—we can’t help but soften our criticism of him.

Let Objects Become Symbols

When your poems confront a speaker’s intense emotion, whether from a real or imagined experience, one thing you can do to stay grounded in real emotion is to turn to images and objects which can become symbols for emotion. Return to Jane Kenyon’s poem “What Came to Me.” Here is an example of speaker who feels an overwhelming sense of grief, but the poem focuses on the gravy boat and that drop of gravy to evoke emotions. The object becomes a symbol of grief.

When experiencing loss or healing from grief, what do people do? We often turn to people, objects, and actions for comfort—the company of our children, a cup of tea, handfuls of birdseed in the birdhouse covered with snow. At the same time, objects can deepen the grief—a pair of empty slippers under the bed, untouched knitting needles in a basket by the couch, the still mobile of stars and planets dripping from a nursery ceiling. These images set a mood for the poem and evoke emotions without the poet having to turn to abstractions and oversentimentality.

Create Distance

When emotions run high, turn down the diction and distance the speaker from the emotion. Rather than rely on hyperbole to describe the overwhelming, indescribable sense of emotion, turn your camera’s eye elsewhere, cool the feelings. Sometimes pulling away creates a contrast that makes the poem more emotional, as odd as that sounds. In the following poem, Kim Addonizio uses this approach:

For five lines, we interpret “going” as maybe implying that the friend is leaving for another appointment or going home. When the friend leans over and dips her bread into the oil on the speaker’s plate, the action can seem like an inconvenience or intrusion. But the mood changes as we discover the friend is losing her hair and is eating as though she is “starving.” We begin to put pieces together until we understand that what’s “killing her” is cancer. Still, even with this knowledge, the tone of the poem remains distant, the speaker objectively describing the scene and actions through imagery. The food is described as “buttery” and “glistening,” which gives the food beauty and a sense of indulgence. In contrast, the friend’s face is “puffy from medication,” which strikes us as being unnatural. Although the speaker never says the words “death,” “cancer,” “loss,” “miss,” or “love,” the cool tone and images create these emotions in us as though the loss of her friend’s life is so devastating that the speaker cannot bring it to words directly. Like the tone, she remains distant from the fact of her friend’s impending death, which can be seen as the poem ends not on “She’s going,” but on “we go on eating.” They go on eating as if nothing is different or wrong. They go on eating because that is life.

In a poem of the same title, Li-Young Lee also adopts a distant tone in the beginning that shifts midway to something warmer:

Eating Together

In the steamer is the trout

seasoned with slivers of ginger,

two sprigs of green onion, and sesame oil.

We shall eat it with rice for lunch,

brothers, sister, my mother who will

taste the sweetest meat of the head,

holding it between her fingers

deftly, the way my father did

weeks ago. Then he lay down

to sleep like a snow-covered road

winding through pines older than him,

without any travelers, and lonely for no one.

Li-Young Lee, “Eating Together” from Rose. Copyright © 1986 by Li-Young Lee. Reprinted with the permission of The Permissions Company, Inc., on behalf of BOA Editions, Ltd., www.boaeditions.org.

For the first five lines, the focus on food sounds almost like a menu description or a recipe. The speaker’s tone is distant as we are given the images of food and who is eating. It isn’t until we reach the eighth line that states “the way my father did” that we feel a sense of absence and longing. The next line surprises us in that the father only disappeared “weeks ago.” We understand that this is a recent loss, and possibly death. The poem affirms that the speaker’s father “lay down / to sleep,” a metaphor for death. And that, further, he lay down “like a snow-covered road / winding through pines older than him, / without any travelers.” The snow evokes cold and the death that comes naturally in winter, and the pines place the father in a world that the old and ancient occupy, alone “without any travelers.” Yet, the poem ends with a tone of acceptance and satisfaction, an affirmation that the speaker’s father is “lonely for no one.” Though the speaker and his family feel loss, emphasized by the assonance of the emotional “oh’s” in the last phrase “lonely for no one,” his father is content and not lonely. This last phrase offers complex feelings, both uplifting in acceptance and painful with mourning. There are two worlds now—life and death—and being “lonely for no one” translates differently in each world. Like Addonizio’s poem, Lee’s poem doesn’t contain the words “death,” or “sadness.” Only a cool tone that arises partially from the imagery produced by a speaker who stands outside the experience of the poem, the eye of the camera an observer rather than a confessionalist.

In the following poem, Albuquerque Poet Laureate Michele Otero writes about an issue about which she feels strongly, though she does not tell the readers what to feel or think about the events described in the poem.

Michelle Otero in Her Own Words:

In 2014 unprecedented numbers of unaccompanied children from Central America were arriving at the US/Mexico border, having traveled more than two-thousand miles across Mexico. The children were bused all over the country to be processed by Border Patrol and then turned over to Immigration and Customs Enforcement. The mayor of Murrieta, California, called on people to fight the transfer of immigrant children to the local detention facility. Protesters met a busload of children with signs reading “go home” and “keep illegals out.” The scene reminded me of other times in our country’s history when ideology has outweighed compassion, when we’ve failed to see children as children. My heart remains broken for what Ruby Bridges and the children on those buses must have felt at having so much anger directed at them.

Your Voice

As readers and students, you may have heard someone refer to a writer and their “voice.” In many situations, we are able to spot a seasoned writer’s voice by noting the subject matter, diction, tone, form, and other aspects of style. It is similar to how we recognize a familiar voice in a crowded room, and then again, it is not the same at all. With writing we miss the timbre of a voice, the auditory sound as air jets passes through the speaker’s unique body and vocal chords.

Still, in writing, there are many ways to use grammar, syntax, and style to create a “voice.” Some beginning writers get caught up in the mission to find or discover their voice. But this is not such an important thing to worry about at any stage of writing—just write. Write about what you know. Write about what you don’t know. Experiment. Play. Don’t think, just write. Your style will naturally evolve, and if you write long enough, it might even change.

Your voice depends on a variety of elements that make up the poems:

Subject Matter:

What do you write about? What don’t you write about? Sharon Olds writes frequently about her father; William Heyen about the Holocaust; Mary Oliver about nature and animals. These subjects are not all that these writers choose to write about, but they do have a heavy, repetitive presence in their collections. What interests you and often becomes the focus of your poems? It’s okay for these to change, too. William Wordsworth wrote about nature when he was young, and much more about God as he aged.

Tone and Mood:

Are your poems serious? Humorous? Dark? Inspirational? When we read Billy Collins we expect to smile and laugh. How do your poems make us feel, generally?

Diction:

Perhaps the most influential element that creates voice and tone is diction, a term we use for “word choice” or the vocabulary used in a piece of writing. There is a range of diction— formal, informal, conversational, slang—and the words we choose reveal the emotional coloring of the speaker and the stance of the speaker in relation to the subject. There are no two words that mean the exact same thing—regardless of what a thesaurus tells you; synonyms are simply related, not exact variants. Diction can also reveal a speaker’s range of knowledge, education, culture, and regional influence. Do you say sneakers or tennis shoes? Soda or pop? Write a list of synonyms for the following words:

- Vulgar

- Obsolete

- Peeved

- Enthralled

- Picky

- Dizzy

- Grass

Choose one of these lists. What are the differences in meaning, nuance, implication?

Syntax and Grammar:

Working hand in hand with diction is syntax, which refers to the order in which words are arranged. We make decisions every day about diction, prepare for phone calls by deciding what to say and how. Syntax is how we deliver our thoughts. If we have to tell someone something important or participate in an intense or touchy conversation, we might even rehearse how we are going to say something to someone before we do.

There’s a difference between telling someone, “I don’t think we should see each other any more” and “I don’t love you.” What we choose to say creates our character in more than one way. Some of what’s related to syntax and grammar are sentence length, fragments, and active or passive voice.

Types of Images:

Like subject matter, writers tend to favor certain images or image types. Read through Michael Burkard’s collected poems and you’ll find frequent uses of trains, rain, and shadows. Some poets’ bodies of work are filled with birds, or flowers, or astronomical metaphors, or images of the body. What images do you gravitate toward? Do you frequently use similes or metaphors?

Form:

By simply looking at a poem on the page we may be able to identify a poet. Emily Dickinson’s short poems with stanzas and lines of equal length. Norman Dubie’s willingness to mix different stanzas and line lengths—a couplet followed by a sextet (six-line stanza), followed by a single line that stands on its own. e.e. cummings’s abandonment of punctuation and capitalization. Are there forms and structures you like to use? Do your lines tend to be long or short?

The combination of all these elements determines your style and contributes to the formation of your voice.

Persona

“A Poet is the most unpoetical of any thing in existence,” wrote John Keats, “because he has no Identity—he is continually in for—and filling some other Body.” In a letter to his brother, Keats famously wrote of the concept of “negative capability,” which he described as “when a man is capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact & reason.” A type of cognitive dissonance in which one can peacefully hold two opposing thoughts in the mind at once, Keats’ negative capability is what allows us as poets to imaginatively and empathetically muse upon the subject of our poems, or to enter the world of another, to speak from an imagined experience as if it were our own. In a persona poem, the poet adopts the perspective of a character or speaker in a specific situation. The poet steps outside his or her own body and into the body of this imagined speaker.

Adopting a persona widens a poet’s range of subject matter. It allows us to explore different subjects and points of view. Rather than only writing from our experience, we can invent a new character or speak from a person in history or in literature. In his book-length poem Shannon, Campbell McGrath speaks from the perspective of the Lewis and Clark Expedition’s youngest member Shannon when he goes missing in the prairie for over two weeks. Based on history, McGrath fills in the events and details no one could ever know. Speaking as Shannon, he writes:

William Heyen, also inspired by history, in his book Crazyhorse in Stillness, speaks from many personas. In the following, he depicts the plight of the buffalo by writing in the voice of an anonymous man hired on the prairie around the time of the Battle of Little Big Horn:

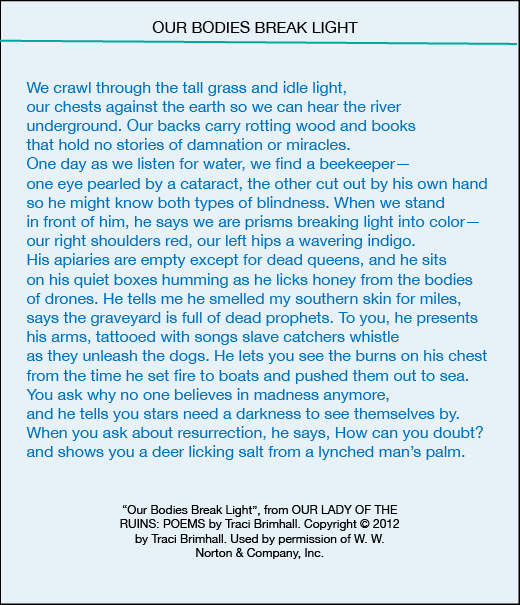

Should you not be so ambitious to write a hundred-page persona poem, or a full collection based on a handful of specific characters in American history, consider writing from the voice of a character with your main focus on theme or circumstance. Here is a poem by Traci Brimhall, whose poems in the book Our Lady of Ruins speak from the personas of multiple women ravaged by war:

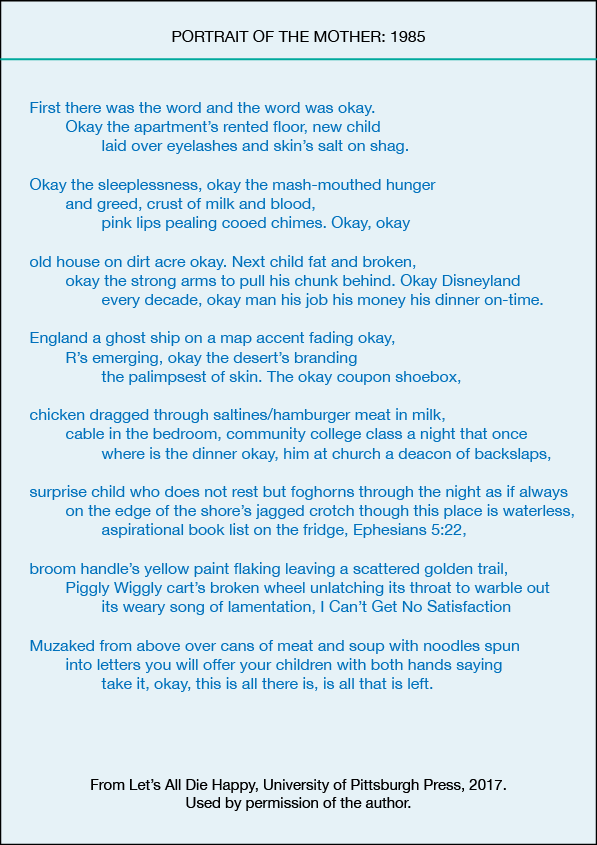

Read these two portrait poems by Erin Adair Hodges, “Portrait of the Mother: 1985” and “Self-Portrait as Banshee”:http://www.pleiadesmag.com/poem-of-the-week-erin-adair-hodges-2/ in which she takes on personas that arise from the speaker’s own experiences in the world, seen and thought through from a new angle.

Erin Adair Hodges in Her Own Words:

“Portrait of the Mother: 1985”

As a relatively new mother at the time I was writing “Portrait of the Mother: 1985,” I was working through what I imagined to be my own mother’s experiences with young children in order understand our very different perspectives on how parenting fits into one’s life, or as is often the case with women, takes it over. Much of my work is also concerned with Christianity through a lens of apostasy, doctrines of male dominionism as viewed by a feminist. The poem all came because of the first line, which made me laugh but also seemed to capture this idea that some live the lives they do not because they choose it but because they believe it has chosen them—that desire has to be sacrificed at the altar of mother-martyrdom.

“Self-Portrait as Banshee”

While “Mother” was a product of long-simmering interests, “Banshee” was more about engaging in play, starting with a scene and seeing where it wanted to spin. Once I got to the speaker offering her Highland ancestry, I realized I had an opportunity to bring in one of my favorite spectral creatures: the banshee. That’s important, though: I didn’t start off with what became the guiding image or centering image. I discovered it through drafting, which is what we as poets must do. We must sublimate our agendas to the poem’s own imaginative will.

Point of View

When we write we do so using one of three points of view:

First Person ● I/We ● I went to the store to buy milk.

Most poets begin writing in first person, taking their own experiences as subject matter. The first-person point of view is present in memoir, the personal essay, and in autobiography, and it allows us to be very close to not only the speaker’s observations, but also with their thoughts. This is the point of view used in a persona poem or a dramatic monologue.

Second Person ● You ● You went to the store to buy milk.

When we use this point of view, we may be addressing a particular person in the poem, or we may be addressing the reader. We may even be talking about the speaker, attempting to make the reader imagine being the “I” which is really the “you.” This perspective can make the reader a character and it can also create a deep sense of connection between the reader and the speaker.

Third Person ● He/She/It ● Her daughter went to the store to buy milk.

From third-person perspective, we can control the distance from which we observe the character by being an omniscient, limited omniscient, or an objective observer.

Additional Resources:

Oliver, Mary. Rules for the Dance. http://maryoliver.beacon.org/2009/11/rules-for-the-dance/169

Longenback, James. The Art of the Poetic Line. https://www.graywolfpress.org/books/artpoetic-line

Adapted from Naming the Unnameable: An Approach to Poetry for New Generations, 2018, by Michelle Bonczek Evory, used according to creative commons CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.