Even before you were born, within your mother’s womb, your body recognized patterns of sound. It began with the beat of your mother’s heart, the swishing of her blood. Rhythm is primal. It is comforting, and it can be startling. When rhythms break, they wake us. When rhythms extend, we become entranced. Rhythm is integral to poetry and a mark of what poetry actually is. In learning to interpret poetry’s structures and sound patterns, our ears attune finely to tone, cadence, pitch, rhythm, and silence in free verse poems. In formal verse, we employ a particular language to help us talk about rhythm.

Meter: Length and Rhythm

In metrical verse, lines can be divided into units of length and rhythm which we refer to as feet, and each foot’s syllable into a stress. Each foot contains either two or three syllables (see below). You may have seen the symbols used to indicate this: ˘ ΄ : the curve marks an unstressed foot, the slash a stress. In the following words, the first syllable is stressed and the second is not: Tennis. Fiction. Music. In the following words, the first syllable is unstressed and the second is stressed: Unlock. Tonight. Against. Using this method of dividing a poem’s lines into feet and stresses is called scansion.

Metrical Lines

Monometer: A one-foot line

│ Therefore

Dimeter: A two-foot line

│Therefore,│ dolphins

Trimeter: A three-foot line

│Therefore, │dolphins │broke through

Tetrameter: A four-foot line

│Therefore, │dolphins │broke through│ happily

Pentameter: A five-foot line

│Therefore, │dolphins │broke through│ happily │and leapt

Hexameter: A six-foot line. Also called Alexandrine when purely iambic.

│Therefore, │dolphins │broke through│ happily │and leapt │into

Septameter: A seven-foot line

│Therefore, │dolphins │broke through│ happily │and leapt │into │daylight

Octameter: An eight-foot line

│Therefore, │dolphins │broke through│ happily │and leapt │into │daylight│in a flash

Metrical Feet

Iamb ˘ ΄ a light stress followed by a heavy stress

- and leapt

Trochee ΄ ˘ a heavy stress followed by a light stress

- dolphin

Dactyl ΄ ˘ ˘ a heavy stress followed by two light stresses

- happily

Anapest ˘ ˘ ΄ two light stresses followed by a heavy stress

- in a flash

Spondee ˉ ˉ two equal stresses

- broke through

If we put these terms together, we can begin to scan lines:

Iambic tetrameter:

Whose woods │these are │I think │I know

His house │is in │the vil│lage* though

(Robert Frost from “Stopping By Woods on a Snowy Evening”)

*Note that feet can break in the middle of words.

Iambic pentameter:

The world │is too │much with │us late │and soon

(William Wordsworth from “The World Is Too Much with Us”)

Trochaic Octometer:

Once up│on a │midnight │dreary, │while I │pondered,│weak and │weary,

Over │many a│quaint and │curious│ volume│ of for│gotten │lore—

(Edgar Allan Poe from “The Raven”)

Scansion contains many words that allow us to speak in a specific way about verse. When a line of poetry adheres to a pattern the poem has undertaken, it is called pure. But often poems are what we call impure. These poems break from the pattern—not to switch to a different meter, which can happen as the examples above show—but to alter the pattern altogether.

Impure Dactylic dimeter:

Hickory │dickory │dock

Iambic trimeter:

The mouse │ ran up │the clock

In the above example, the first line is impure. Here is another example of an impure rhythm, but one that follows another named pattern: catalectic:

Trochaic tetrameter:

Tyger! │Tyger! │Burning │bright

In the │forests │of the │night

(William Blake from “The Tyger”)

These lines by Blake are catalectic because the final foot is cut off. It also contains lines that end with a stressed beat in what we refer to as a masculine beat. If the last beat were unstressed, we’d refer to it as feminine.

The art of scansion is both scientific and subjective. This specialty language allows us to examine poetry in a calculated way, but there are times when the degree of stresses sound different to different ears.

There are many good sources on scansion and I want here to simply provide the basic language you may use to speak about poems, and to understand the detailed rhythms of your own poems. Scansion can be useful in discovering where language goes slack by identifying words that produce less energy, like prepositions. It can also allow you to identify places in poems that move you, allow you to hear what patterns you are drawn to as a reader and writer.

Music and Rhyme

In addition to line length and rhythm, we also categorize lines by rhyme, especially in formal verse where an extended pattern is maintained. You most likely have been rhyming from an early age. Children’s books written by writers like Shel Silverstein and Dr. Seuss have delighted both children and adults with their rhyming stories. Rhyme makes language memorable and pleasurable. In both formal verse and free verse, rhyming is elemental. In formal poetry it occurs more frequently as end-rhyme, when two or more words that end lines rhyme. In free verse, the rhyme is more likely to be internal, not necessarily occurring at the end of lines.

Let’s take a look at an excerpt from William Wordsworth’s poem “The Daffodils”:

Here we can see the first and third lines rhyme; the second, fourth and sixth; and the fifth and sixth. There is a definite rhyme scheme. When we refer to the rhymes in this stanza, we diagram the rhymes with matching letters like this: ABABCC.

I wandered lonely as a cloud (A)

That floats on high o’er vales and hills, (B)

When all at once I saw a crowd, (A)

A host, of golden daffodils; (B)

Beside the lake, beneath the trees, (C)

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze. (C)

The letter changes whenever the rhyme changes, and whenever a new rhyme is introduced you add a new letter.

In this example, Levine uses rhymes that are both internal and slant, or off, rather than exact: sacks, black, shafts; butter, tar. Even the numerous occurrences of “out” paired with “creosote”creates a kind of slant rhyme. Here is another example:

In this example, the second line contains a slant internal rhyme: “ten” and “ton,” which also rhyme with “hands” in line one. These sounds are tightly woven and where there isn’t rhyme, per se, there is assonance, similar vowel sounds, or vowel rhyme: green, tease, deep; and slime, pile, ice.

In these first two stanzas of the poem, Jeffers’ use of m, p, and f, create three strains of alliteration. In addition to alliteration, we can further label the f sounds as an occasion of consonance, what Edward Hirsch defines as “the audible repetition of consonant sounds in words encountered near each other whose vowel sounds are different”—flower-fades-fruit: flow-fay-frew.

Line Length

If you simply browse the poems included in any anthology, you will see all types of shapes on the page. The length of the line is one of the most important decisions a poet makes about a poem, and the decision usually comes to define a poet’s style. Robert Creeley’s poems use short lines. C. K. Williams, long. Most poets write somewhere in between. The decision of how long to make lines can be driven by a number of factors, but mostly it is chosen by prosody, the musical component of the language that projects the speaker’s voice and breath. As we’ve seen in the last chapter, where we choose to break lines also has a tremendous effect on the poem’s tone and meaning. One of the elements that determine line length is the character of the language in which you write. English contains many iambic patterns that often sound most right on a line between four and five feet long. Lines one foot long are barely poems at all; it is difficult to create tension or musical phrases with only two beats per line. Lines with four feet are frequently used to tell stories, as is the case often with Robert Frost’s poems. Longer lines lend themselves well to conversational tones, like that of Denise Duhamel’s, or in lyric poems like Larry Levis’s. Some poets like Allen Ginsberg and Charles Olson, who wrote about it in his essay “Projective Verse,” considered a line to be a unit of breath. Olson writes:

And the line comes (I swear it) from the breath, from the breathing of the man who

writes, at the moment that he writes, and thus is, it is here that, daily work, the

WORK, gets in, for only he, the man who writes, can declare, at every moment, the

line its metric and its ending—where its breathing, shall come to, termination.

There can be no denial of the essential relationship between the poetic line and breath. Or between any carefully constructed writing and the pace at which it’s read. Just look at Olson’s passage and his use of commas, which causes us to stagger through the sentence. Poetry is an oral art which comes fully to life when read aloud. Lines are instructions for how often and how long to pause. Like sheet music, the lines guide our pace, emphasis, and silence. If you were to read short-lined poems, however, taking a new breath at each line’s start, you’d sound like a panting dog. So, there is some room for interpretation on Olson’s assertion. Nonetheless, breath and line are intertwined, as you will see from the following examples.

As we read through these, note the different line lengths and their effects:

In this excerpt from Robinson Jeffers’ poem “The Eye” we see the different effects that long and short lines have on the breath. The first lengthy line is full of images beyond the human—the headlands, the mountain, the shore, the dolphin, the smoke. In a long line like this we are given a sense of being overwhelmed as the images keep building and drawing out the breath until we are breathless. Compare this line to what follows two lines below: “Eyeball of water, arched over to Asia.” If you read both out loud you can feel how the length changes the way you use your lungs: long breath, short breath. The effect of the shorter line is like a quick glance—the eye open from the Pacific coast to Asia.

Rather than breaking the line after words or phrases to create a pause, many poets incorporate white space into the line itself. Here, the spaces in line four visually mimic the footsteps referred to in line three, as well as create the pacing—as though the steps being taken are slow. Notice that the phrase “Your voice,” which is part of the list in line four is moved to line five. That means there must be some difference between the effect created between the phrases with white space and those created by line breaks. It seems that the pauses between the list in line four are slightly shorter, more staccato, than the pause created between “bone wings” and “Your voice.” The more poetry you read, and the more poetry you write, the more you will begin to identify the subtleties of these techniques.

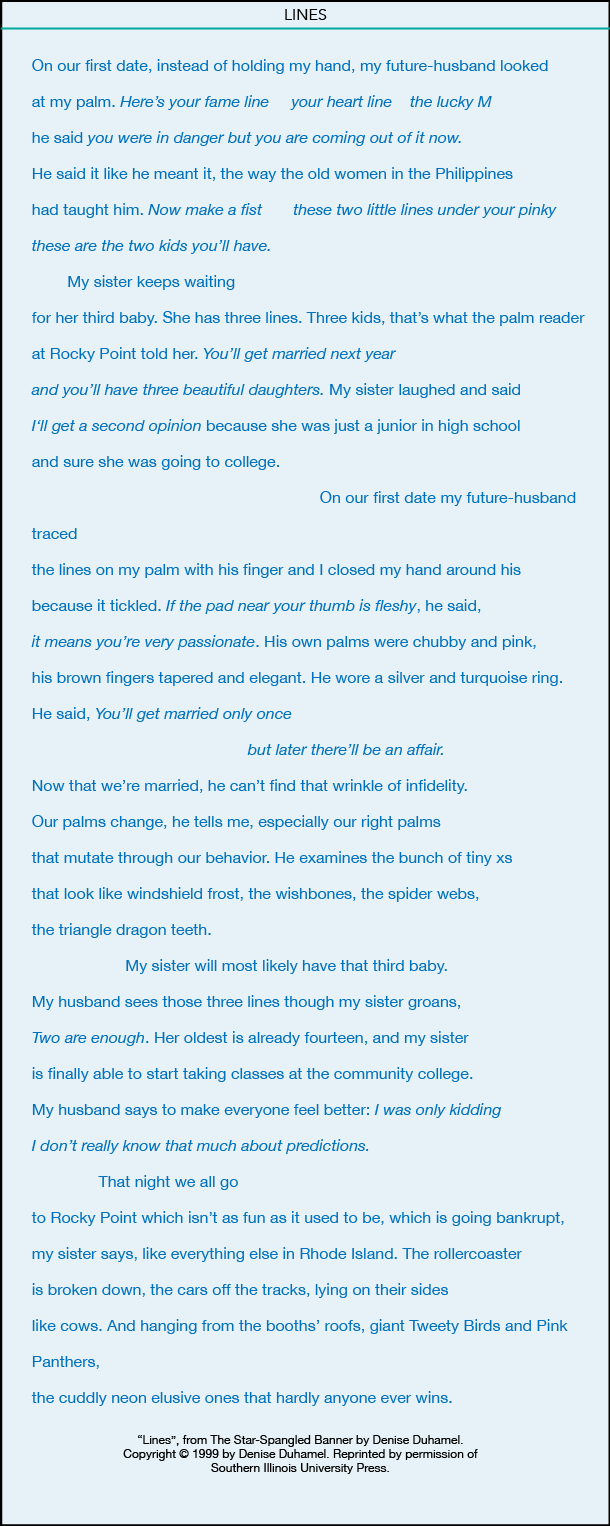

One of the most conversational of contemporary poets, Duhamel speaks to us like we are a long-time friend. Her voice is energetic though the lines are long. And in this poem she varies line lengths drastically but keeps to an overall pattern so it still looks uniform on the page. Once again, like other poems we’ve looked at, the form reflects and enhances the subject: the lines on our hands that palm readers use to predict our future. As we read the poem, we read the lines as though we are scanning a palm. In addition to the visual echo, the spaces also create pauses that mimic the way a fortune teller speaks: slowly, interpreting, considering—“He said, You’ll get married once / [space] But later there’ll be an affair.” The space also creates suspense and drama. In this excerpt, there is one line on which only one word sits: “trace.” It is the only line in the poem that contains one word. What is the effect? Why this word?

Additional Resources:

Skelton, Robin. The Shapes of Our Singing. http://www.amazon.com/The-Shapes-Our-Singing-Comprehensive/dp/0910055769

Strand, Mark and Eavan Boland. The Making of a Poem. http://books.wwnorton.com/books/The-Making-of-a-Poem/

Adapted from Naming the Unnameable: An Approach to Poetry for New Generations, 2018, by Michelle Bonczek Evory, used according to creative commons CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.