Put simply and directly, creative writing is the language of images. Whereas other forms of writing like news articles, academic essays, and instruction manuals relay information from the writer to the speaker in order to inform or instruct, in fiction and poetry images translate the world to text so a reader may experience.

If you are a creative writer, you are an image creator. And to be a master image creator, you need to be really good—really, really good—at finding ways to stimulate a reader’s senses through significant, concrete detail. When poets write, they see through the speaker’s eye, what we call the mind’s eye. By writing through the mind’s eye, you describe what the speaker sees in order to recreate the world of the speaker on a page so then the reader can translate those words back into images and experience the poem.

Language is Physical

If we examine the words associated with the act of writing, we find that language is directly rooted in the physical world of the body. Let’s consider the answers to the questions below.

Imagination. Imagine. Image. This is the language of creative writing and what the Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines as “a mental picture.” When we read, our mind processes the words into mental images with our five senses—sight, smell, taste, touch, and hearing. When we are writing poetry we want to give our readers the world in its raw, physical, concrete form. The more specific we can be, the better.

For example, note how the following descriptions affect your physical, emotional, and mental experience differently:

- The child was sad because it was her first day of school.

- Standing in the doorway between the dark interior of the classroom and the sunny sidewalk, four-year old Meredith twisted her mother’s flowered skirt in her hands, hid her face in its folds, and stained its red silk with her mucus and tears.

The second example is much more detailed and imagistic than the first. It, therefore, engages our senses and emotions much more directly.

In example two above, vivid details invite your senses to take in the scene. But once a piece of creative writing contains specific images and details, those details begin to have an additional effect on the reader’s intellect as the images resonate into symbols and create connections and suggestions.

- What effects do the images in the above example have on your intellect?

- What types of connections, contrasts, resonance, and suggestions do the images make? For example, notice the contrast between the shady classroom and the sunny sidewalk.

- What types of interpretations does this image invite?

Sensation. Sensual. Sense. This is how we make sense of the writing. How we make sense of the words on the page. We do not understand through abstract thought. We understand mentally through what our eyes, ears, nose, mouth, and skin understand physically. Merriam-Webster defines “sense” as: One of the five natural powers (touch, taste, smell, sight, and hearing) through which you receive information about the world around you.

One of our five natural powers. The word “power” makes us sound supernatural; but these are not supernatural—they’re natural to our bodies. Poetry enables us to use and sharpen them.

The second and third definitions reflect the impact of poetic images on a reader. These poetic images produce vision in the reader by manifesting “to the senses” “something immaterial.” In other words, a reader’s senses react to the vision, or images of an “object,” created by the poem as though that object were real. With poetry, those images give way to “a thought, concept,” or idea. In the above example describing Meredith’s first day of school, for instance, we are led to the thought or concept of how she is sad via the images.

When we consider the genres of novel, essay, and poem, among the most relevant things we see is the use of images and description. These genres immerse their readers in a different world, one which values and believes in the power of language to stimulate our senses and transport us somewhere new. And the most successful ones, the masters like John Steinbeck or Ross Gay, are able to access our brains in the same way that real-life experiences do, producing in the reader feelings and thoughts and insights generated intelligently by the processing of sensory information.

The Purpose of Poetry

If you’ve taken a composition or freshmen writing course, you might recognize some of these terms: summarizes, sources, persuades, ethos. These words you will rarely if ever use in reference to writing poetry. And why is that? Well, what’s the purpose of poetry? Perhaps this is not an easy question to answer. In fact, the answer might depend on time and culture. Epics such as Gilgamesh aided in memorization and preserved stories meant to be passed down orally. The British Romantics valued the pleasure derived from hearing and reading poetry.

In some cultures poetry is important in ritual and religious practice. In contemporary times, many describe poetry as being a tool for self-expression. In the excellent glossary in his book How to Read a Poem and Fall in Love with Poetry, poet Edward Hirsch provides the following definition for a poem:

Poem: A made thing, a verbal construct, an event in language. The word poesis means “making;” and the oldest term for the poet means “maker.” The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics points out that the medieval and Renaissance poets used the word makers, as in “courtly makers,” as a precise equivalent for poets. (Hence William Dunbar’s “Lament for the Makers.”) The word poem came into English in the sixteenth century and has been with us ever since to denote a form of fabrication, a verbal composition, a made thing. William Carlos Williams defined the poem as “a small (or large) machine made of words.”

(He added that there is nothing redundant about a machine.) Wallace Stevens characterized poetry as “a revelation of words by means of the words.” In his helpful essay “What Is Poetry?” linguist Roman Jakobson declared:

“Poeticity is present when the word is felt as a word and not a mere representation of the object being named or an outburst of emotion, when words and their composition, their meaning, their external and internal form, acquire a weight and value of their own instead of referring indifferently to reality.”

Ben Johnson referred to the art of poetry as “the craft of making.” The old Irish word cerd, meaning “people of the craft,” was a designation for artisans, including poets. It is cognate with the Greek kerdos, meaning “craft, craftiness.” Two basic metaphors for the art of poetry in the classical world were carpentry and weaving. “Whatsoever else it may be,” W. H. Auden said, “a poem is a verbal artifact which must be as skillfully and solidly constructed as a table or a motorcycle.”

The true poem has been crafted into a living entity. It has magical potency, ineffable spirit. There is always something mysterious and inexplicable in a poem. It is an act—an action—beyond paraphrase because what is said is always inseparable from the way it is being said. A poem creates an experience in the reader that cannot be reduced to anything else. Perhaps it exists in order to create that aesthetic experience. Octavio Paz maintained that the poet and the reader are two moments of a single reality. Of the many ideas provided here in this definition, perhaps the one to emphasize most is that the poem is “an event in language.” It is also one of the harder to understand concepts. “A poem creates an experience in the reader that cannot be reduced to anything else,” writes Hirsch. Especially not through paraphrase. This means that in order to “experience” a poem, a reader needs to read it as it is. The poem is itself a type of virtual reality.

Jeremy Arnold, a professor of Philosophy at the University of Woolamaloo in Canada, likens the poem to the “pensieve” device in the Harry Potter series: “A poem allows someone to preserve a mental experience so that an outsider can access it as if it were their own.” When coming to poetry, there may be nothing more important to understand because nothing can shape your perspective more on how to write and for what purpose. Poetry requires a reader, an audience; therefore, the poet must learn how to best engage an audience. And this engagement doesn’t happen by sharing ideas, feelings, or experiences, by telling the reader about your experiences—it happens by creating them on the page with words that evoke the senses. With images. These, then, are how the literary genres speak. Images are their muscles. Their heart. Images are poetry’s body and soul.

“Show Don’t Tell”

How many of you have heard this phrase before? Maybe you heard it in your high school creative writing or English classroom. Or maybe this is the first time you are hearing it. The adage “Show don’t tell” is shorthand for the most important tenet of creative writing. It asks you to create with an attention to the concrete, physical world rather than to simply tell with abstract words which produce thoughts about the speaker’s experience or ideas (instead of feelings in the reader’s body through the five senses).

In the following poems, images can not only be seen, but heard, tasted, smelled, and felt. Here are some examples of the different types of imagery we use in poetry. Many use more than one kind:

Notice not only how imagistic these examples are, but how specific the details are, as well. In the poem “Hat Angel,” Michael Burkard recreates the sound that the train makes in the last two lines through his use of diction and line breaks. And in “Kinky,” Denise Duhamel attends to the small details of a Barbie doll—“the small opening under her chin” while Robert Evory in “Garlic” brings our eye to the meeting of the delicate paper of a garlic clove and a fingernail.

These poems describe a pair of pants, a Barbie doll, and a garlic clove the way we would see them if we were holding them in our hands. And with Billy Collins in his poem “Osso Bucco,” we get the sense that we are looking closer and closer and closer at the meat on his (on our!) plate. In these examples, the reader must be—cannot avoid being—sensually immersed in these images, which trigger the five senses—sight, taste, smell, touch, and hearing—through memory and imagination to create an actual experience for the reader. We do not read about George Trakl’s experience on the water in the poem “Sun”; we are there ourselves.

Adjectives and Adverbs

In an effort to create sharper, clearer images, beginning writers tend to add adjectives and adverbs to their sentences:

The sun shone brightly on the relaxing lake.

The flower is beautiful.

In each of these sentences adjectives and adverbs make for vague, generalized images by presenting ideas rather than things. What does it mean that the lake is “relaxing”? It is an idea and therefore does not produce a specific image in your mind’s eye. What image is brought to mind with the word “beautiful”?

Although it may seem counter-intuitive, relying on adjectives and adverbs actually dulls an image rather than sharpening it. They tell a reader rather than show a reader by providing judgments made by the speaker. To remedy this, we need to sharpen the images through expansion or tightening:

The sun shone on the flat surface of the lake reflecting the purple evening light and

the white-capped mountains in the distance.

The tulip spread its petals wide creating a circle yellow as the sun.

Sticking to concrete, specific details engages readers’ senses and allows them to come to the conclusion of whether or not the lake is relaxing or the flower beautiful.

Abstract vs. Concrete Words

The success of the above poems results in the poets’ uses of concrete images, the images that refer to things you can actually touch in real life. In poetry, we work with two types of words:abstract and concrete. Ideally, the poem should re-create the experience of a poem through concrete details so the reader isn’t merely told about the experience through the speaker, but shown the experience which the poet re-creates in a way that engages the reader’s five senses.If the poets had used mostly abstract words, their poems may not be, well, poems. They might tell us more than show us. They might report or summarize. For example, if Gary Snyder relied more on abstractions than concretes, “The Bath” might tell us outright how he feels about washing a baby or how the baby feels about being washed rather than creating images of the baby being washed. The concrete images create a scene and allow us to come to our own conclusions. Here is an example of what Snyder’s poem might look like if it relied too heavily on abstractions:

The baby was scared

but we were happy

in the sauna washing him

because we love him

and his body so much.

The sentiment in these lines is intimate and warm, but as readers we struggle to see the event in our mind’s eye. But note, even with the abstractions, the poem cannot escape using some concretes—baby, sauna, body. Rather than putting us in the room with the bath and allowing readers to feel the actions and be there themselves, the poem shifts its spotlight on the feelings of the speaker.

To better understand, let’s look closer at abstract words. Here are some examples:

- Love

- Fear

- Happiness

These are what we call abstract words. They refer to ideas we think with our minds rather than specific, individual things we can feel with our five senses and that call an exact image into our mind’s eye. Think of concrete words as something you can actually touch. You cannot touch“love” and “safe” but you can touch your son in “warm water / Soap all over the smooth of his thighs and stomach.” Once you finely tune the images into specific, concrete details, the sentiment will come through naturally.

Sometimes this concept confuses my students. “But I can feel love,” they say. “I can feel anger.”And, yes, of course we can recall what those emotions feel like when they are referenced in a poem. And, in fact, we feel actual sensations brought on by these emotions when they happen.Our blood races when we’re in love, our stomach jumps when our lover or someone we desire walks into sight. We may feel our chests swell when we think about our mothers and our fathers, but when we read abstract words like “love” and “anger” we experience them in a vague, cloudy way, reliant more on our own individual memories that involved our five senses, rather than the poem itself using our five senses through imagery to create a new experience and memory.

Trying to avoid concretes is difficult. In fact, in order to even explain to you the sensations we feel when we experience love, as I just did, I had to use much more specific language that refers directly to physical things—chest, blood, stomach. Lover, mother, father. We read the word “love” and imagine love; we do not have a specific image come immediately into our mind’s eye. And immediacy is the poet’s job and responsibility to the reader of poems—words should vanish. The walls between the experience created by the words and the reader’s senses taking in that to which the words refer, should fall. When we read good writing, we get lost in the experience and images the words are creating in our minds. We are transported.

In contrast to abstractions, take in these words:

- Apple

- Blue

- Boat

What happened? What do you see?

Go around the room and have each class member share the image that comes to mind with the above words. How many different images are there for apple? Blue? Boat?In a poem, we want readers to have a specific experience created by images. The above words bring images to our mind, but we can do better still by being even more specific.

Use Specific, Significant Details

Now, what if we were to make these words even more specific:

- Apple … Golden Delicious Apple

- Blue … Turquoise blue

- Boat … Sailboat

Now the brain is working more quickly. We see these things more immediately in our mind’s eye.

In the poem “The Bath,” Gary Snyder is very attentive to specific details. He names his son, Kai, places us in a sauna, describes the lantern as being kerosene and set on a box. There is not a window, but a ground-level window which the light from the lantern illuminates. The light also illuminates not the stove, but the edge of the iron stove. Kai’s body stands not in water but warm water, and it’s not his body that is soapy—but his thighs and stomach.

Snyder creates a concrete, physical world for his readers and places us in a very specific time and setting. The details feel like they are slowed down—in both the writing and reading process—so the event may be created on one side and taken in on another. Snyder slows down and looks closely so we may, too.

Once details become this specific, something magical begins to happen. The poem naturally begins to amass different levels of meaning; it grows in complexity. For example, what’s the significance of the lantern being kerosene? What does that tell us about the setting? The speaker? What do we take away from the detail about the ground-level window? What ideas come to mind when we read “ground-level”? Once we attain a literal reading, a first reading, which creates the scene, we may look again only this time more closely at the words, the diction. We may notice that “ground-level” evokes a sense of simplicity in us, an idea about being closer to the earth, being grounded. If so, how then does this feeling and idea relate to the poem as a whole?

This symbolic way of reading of poetry happens naturally when images are concrete, and details specific and significant. Snyder could have used any words in the poem, but he used these. Why? What do these words do inside their poetic space? What we do as writers affects the way readers read our poems. But when we write—here’s the catch—we don’t necessarily have to think of how a reader will interpret and read the poem. We just need to concentrate on making the words we choose be specific and significant so language—naturally symbolic—can do its thing. After all, Alexander Fleming didn’t discover penicillin by setting out to cure disease—he saw some mold growing, tapped into his curiosity, and used his imagination.

Read the poem “What Came to Me” https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poem/what-came-me by Jane Kenyon and note how the poem thinks small but produces big feelings. The poem’s use of line, sound, tone, and image creates a moment in which the speaker is overwhelmed with grief. And what causes this for both the speaker and the reader? Finding a drop of gravy on the porcelain lip of a gravy boat. One “hard, brown / drop.” Why does this image have such power? It is a short poem—nine lines—and those lines are short, ranging from four syllables to one line that is seven syllables long. But although brief, it is compact and bursts with emotion. We are not told how the speaker feels.

She does not say she felt sadness, pain, remorse, or loss. The first line describes action, simply,“I took.” And the penultimate, the second-to-last, line also describes an action: “I grieved.”Kenyon doesn’t write “I felt grief” (a filter) or “I thought of all the good times” (a cliché). Instead, we are there with her, lifting the gravy boat from the box, only to discover in line five, a “hard, brown” and in line six, “drop of gravy still.” The word “still” here doubly stops time and implies no movement while it also ends the line and hangs there, still on the sixth line’s edge just as the gravy drop is on the edge of the gravy boat’s lip.

As Hirsch writes, “A poem creates an experience in the reader that cannot be reduced to anything else.” The effect of Kenyon’s poem cannot be reduced only to the image of the gravy drop. As said, the diction, sound, form and tone do a lot of work. But it cannot be denied that the image is central to the poem’s effect. And when it is combined with all the other poem’s elements, it produces an experience that cannot be replicated any other way.

Write What You See

…not what you think. Thoughts explain, report, conclude, reflect, and basically do the opposite of what images do. With images, readers are left to come to their own conclusions, reflections, ideas, analyses, and insights. And readers like it this way. They don’t want to be told what to think and feel. They don’t want to be told the ending to a movie that they haven’t yet seen. When we tell instead of show, when we use conclusions to inform readers rather than evoke their senses, we steal the pleasures of literature from them. The pleasure of reading literature, and therefore poetry, comes from being able to reflect on what you experienced and form your own conclusions. When we read a story, we want to go along for the ride and lose ourselves with our imaginations. In writing, we say trust your reader. It means letting the images and actions exist without our interpretations. If a reader wants interpretations they will reach for a book of criticism, an essay, or the editorial section of a newspaper.

Often in creative writing classes, beginning writers rely heavily on saying how they feel and what they think rather than describing what they see. Perhaps this is because beginning writers are used to being asked for their thoughts in classes like composition and courses in literature. But here we are writing the literature. Not interpreting it. It’s a different kind of writing.

When revising, try to change thoughts to images. It’s okay to have thoughts, what Ezra Pound called logopoeia, at any stage in the writing process. The trick, as poet Bruce Smith once so eloquently wrote, is “not getting rid of thought, but finding a way to realize and music the thought.” Note the word “music” being used as a verb—music your thought. When we revise, poets will sift through a poem over and over making images more succinct, diction more precise, lines more musical.

Zoom In, Zoom Out

One way to enable yourself to see things more vividly when you write is to imagine that your mind’s eye is a camera. And, like a movie camera, it can zoom in and out. It can move outside a house, inside a house. It can be on a roof, in a basement, and in orbit all in one poem. How boring would a film be if the camera stayed in one spot the entire time? Move your lens around. Change out the telescopic lens in one line for a microscopic lens. Use a wide angle in partner with a 50 mm, which captures things closest to their actual size. And, as any good photographer knows, when photographing a subject, try a different angle. Instead of taking shots from only above the bird’s nest, move to the side, see what’s below.

When taking pictures one cannot use a filter to make a photograph say, “I thought the blue egg looked like a sapphire.” Nope. Instead, the photograph can only show a sapphire-blue egg. The photographer’s opinion doesn’t exist in the picture; they stay behind the lens. So, too, with the poet. Stay behind the lens and let the images and their sequence speak for themselves. The fact that the poet points the camera in a specific direction already tells the reader that the speaker/photographer/poet believes this is important to see.

Just as a camera-operator must be present in their surroundings when filming, so too the poet must locate themselves in the setting—be it time, place, or mood—of the poem. Pay attention to what your senses detect. What do you see, hear, smell? Who is with you? Who was here before?

Look around. Orient yourself.

Begin by locating yourself very specifically in a moment with your lens. Then, move out from there—through time, through space. Try not stay in one spot. Don’t stagnate and bore your reader. You can go anywhere, any time. Think of chaos theory and the butterfly effect: if a butterfly flaps its wings halfway around the world, does it cause something else to happen on the other side? It doesn’t matter. A butterfly flaps its wings on a dry stone at the edge of Otsego Lake’s shore. In Seattle, a meteor lights the sky. Are these connected? It doesn’t matter—they can both exist in a poem and, therefore, be connected. Or not. What else do you want to see? Pick up the camera and go.

Use Active Verbs

Earlier we spoke about filters and how removing them can make your writing more energetic. Another way to add energy to your writing is to use active sentences and specific verbs. Verbs are amazing little things. They may be only one part of speech but they’re the one that provides motion or stillness that define a subject or event. Verbs affect tension, energy, and pace. And just think about it: grammatically, a sentence cannot exist without one. Of course, such is the way of the world: not all verbs are created equal. To be forms of verbs create passive sentences, which slow down the pace, zap energy from writing, and tend to create generalized images. They add unnecessary syllables to an art form whose purpose is to be concise and condensed. They appear as the following:

Present Tense

- I am, we are

- You are, you are

- He/she/it is, they are

Past Tense

- I was, we were

- You were, you were

- He/she/it was, they were

Progressive Form

- I am being, you are being, he/she/it is being

Perfect Form

- I have been, you have been, he/she/it has been

Here is an example of a sentence that uses the to be forms of wash and vacuum:

I was washing the dishes while my brother was vacuuming the carpet.

And here is that sentence rewritten with active verbs:

I washed the dishes while my brother vacuumed the carpet.

Notice how the change creates a sentence with more stresses thereby creating more energy. Now take a passive sentence that places the emphasis on the milk:

The milk was spilled by Hector.

An active sentence that focuses our attention on the subject’s action:

Hector spilled the milk.

Though passive sentences have their place and create their own effect by shifting emphasis from the subject to the object, generally they should be used sparingly.

In addition to using the active forms of verbs, experienced poets use a wide variety of verbs in their writing. As you revise, don’t settle on the first verb you think of; every verb can offer something different. For example, did the little girl look out the window at the deer? Or did she gaze, peer, stare, glance, glimpse, notice, or behold? All of these words produce a slightly different meaning and music.

When revising your poems, a thesaurus can be a useful tool when expanding your vocabulary.

Anglo-Saxon vs. Latinate Diction

The English language is a combination of Latin and German. As you begin to expand your vocabulary by experimenting with different verbs that make your images more specific, keep in mind that for a poet, short and succinct Anglo-Saxon verbs often work better than Latinate, multi-syllabic verbs. Though all words have their place, those Latinate, so-called “SAT words” or “ten-dollar words” slow down your reader. They are intellectual rather than physical; of the mind rather than of the body. Anglo-Saxon words tend to be shorter and more concrete, whereas Latinate words tend to be longer and more abstract:

| Latinate | Anglo-Saxon |

| Masticate | Eat |

| Abdomen | Tummy |

| Inquire | Ask |

| Disclose | Tell |

| Cognizant | Aware |

| Excrement | Shit |

| Precipitation | Rain |

Think about how and when you hear these words. If you stub your toe or slam your finger in a car door, I bet most of the words you say would be monosyllabic and Anglo-Saxon rather than multi-syllabic and Latinate. The shorter words are more immediately felt, whether exclaiming them or reading them. When people become excited, their words shorten and the pace of language quickens. There is more urgency and more energy—what we want in our poems.

Sometimes students worry that their poems will be too remedial if they stick to shorter words. Though there is nothing wrong with a reader having to use a dictionary on occasion, remember that creative writing is the land of images. We want our readers to forget they are reading. We want them to experience a poem through their senses. Poems are condensed moments of an experience meant to be taken in as a whole; all at once, in a way, no matter the length of the poem. We want the words on the page to translate into images in the mind’s eye quickly; therefore, big, academic words are usually not the diction of choice in poetry.

Figures of Speech

Figurative language uses words or expressions not meant to be taken literally. Whether you realize it or not, we encounter them every day. When we exaggerate we use hyperbole: I’m so hungry I could eat a horse; when Rhianna sings about stars like diamonds in the sky she uses simile; when we say opportunity knocked on my door we are using personification. In addition to making our conversations interesting and capturing our intense feelings, figurative language is very important to the making of poetry. It is a tool that allows us to make connections, comparisons, and contrasts in ways that produce insight, raise questions, and add specificity. Earlier we worked to make words more specific. We changed apple, blue, and boat into golden delicious, turquoise, and sailboat. The changes made the images more immediate and sharper and offered the reader opportunities to understand the poem. Figures of speech are the next step to adding layers to your poems, to adding even more complexity and meaning.

Types of Figurative Language

Figurative language, often the comparison made between two seemingly unlike things, is almost all image-based and, therefore, a good friend of poetry. In fact, some, like Owen Barfield in his essay on metaphor https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/text/metaphor , would go so far as to say that poetry is metaphor:

The most conspicuous point of contact between meaning and poetry is metaphor. For one of the first things that a student of etymology—even quite an amateur student—discovers for himself is that every language, with its thousands of abstract terms, and its nuances of meaning and association, is apparently nothing, from beginning to end, but an unconscionable tissue of dead, or petrified, metaphors. If we trace the meaning of a great many words—or those of the elements of which they are composed—about as far back as etymology can take us, we are at once made to realize that an overwhelming proportion, if not all, of them referred in earlier days to one of these two things—a solid, sensible object, or some animal (probably human) activity. Examples abound on every page of the dictionary. Thus, an apparently objective scientific term like elasticity, on the one hand, and the metaphysical abstract on the other, are both traceable to verbs meaning “draw” or “drag.” Centrifugal and centripetal are composed of a noun meaning “a goad” and verbs signifying “to flee” and “to seek” respectively; epithet, theme, thesis, anathema, hypothesis, etc., go back to a Greek verb, “to put,” and even right and wrong, it seems, once had the meaning “stretched” and so “straight” and “wringing” or “sour.” Some philologists, looking still further back into the past, have resolved these two classes into one, but this is immaterial to the point at issue.

“Nihil in intellectu quod non prius fueriot in sense.”

“Nothing in the intellect that was not previously in the senses,” wrote philosopher John Locke. In short, the way we know anything is through the senses—even abstract idea originates through experience gained through our bodies. And in the case of language’s origin, as explained above, it appears that all words, at their invention, referred to something concrete—an object or a specific action that evoked the senses. As we continue to use words, they evolve, for they live their own life. And when we use a word, we invite its history and permutations into its meaning. Of course, this is all way too much to think about at once in the writing process. But it is why writers revise and cross-examine their diction, thinking out what meanings the word may suggest. Language is naturally symbolic in origin, in its fabric. And an art that uses words cannot help but also have more meanings than just the literal.

The following types of figurative language are used most often in poetry:

- Metaphor—A direct comparison between two unlike things, as in Hope is the thing with feathers (Emily Dickinson, “Hope”).

- Simile—A comparison that uses like or as, as in something inside me / rising explosive as my parakeet bursting / from its cage (Bruce Snider, “Chemistry”)

- Personification—Human characteristics being applied to non-human things, as in irises, all / funnel & hood, papery tongues whispering little / rumors in their mouths (Laura Kasischke, “Hostess”).

- Metonymy—When one thing is represented by another thing associated with it, as in The pen is mightier than the sword (where pen stands in for writing, and sword stands in for warfare or violence).

- Synecdoche—When a part of something symbolizes the whole, or the whole of something symbolizes the part, as in All hands on deck (where hands stands in for men), or The whole world loves you (where whole world represents only a small number of its human population).

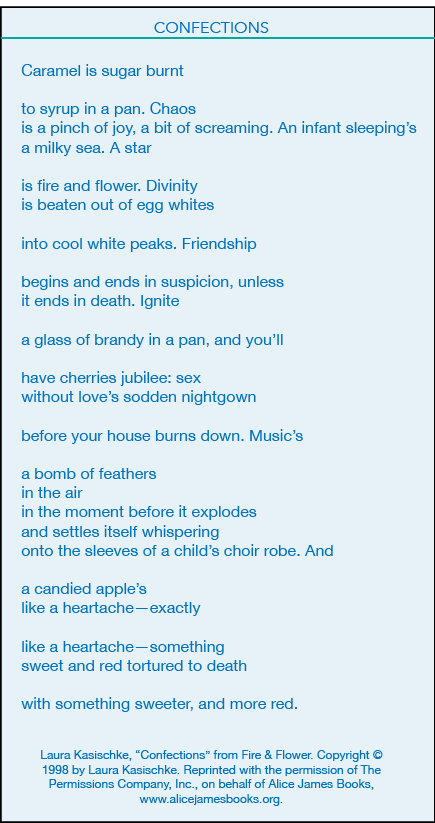

When we read such literary devices, our mind lights up a new pathway between the two things and we discover new ways of thinking about the relationship between these two things. We wonder, how is his love a red, red rose? But before we wonder, our senses have already made a connection. As we look closer at the poem, we begin to explore the idea more. The following is a poem by Laura Kasischke. It contains numerous metaphors and similes:

The poem begins with a sentence that mimics a metaphor—stating something is something else: caramel is sugar burnt / to syrup in a pan. It sounds like a metaphor, but it actually isn’t. Caramel actually is sugar burnt to syrup. Rather than a metaphor, the first two lines function as a definition, which sets the stage (note my own figurative language) for understanding how metaphors work in our minds, for whether definition or metaphor, we use the same structure: x is y; our minds equate the one thing with the other. In the poem this happens with caramel to sugar burnt to syrup.

In “Confections,” the opening definition that looked like a metaphor is followed by a true metaphor (or is it?). Chaos is a pinch of joy, a bit of screaming. We take this as metaphor, but because we do, it brings us back to the first sentence. If sentence two is figurative why isn’t sentence one? And if sentence one is literal, why isn’t sentence two? Both are structured exactly the same. Kasischke’s poem exposes the slipperiness of language and syntax: how we use them and interpret them. The poem asks us to examine closely the line between imagination and reality and the role language plays in sorting them out, or not.

The next two metaphors are more imagistic that the previous: An infant sleeping’s / a milky sea. A star / is fire and flower. While we couldn’t “see” the abstraction joy and could only hear screaming, we certainly see a milky sea, and we certainly see a star flaring as fire, and flower. The parallel of fire and flower is interesting because they are so different. A flower would not survive if it were ablaze in flames. Yet, Kasischke’s comparison between the star and fire and flower makes sense to us. It plays not on the science of heat, but on the images associated with fire and flowers—they both spread outward. So, we equate the shape and motion of a star with both fire and flower. Of course, like the comparison of caramel to sugar burnt to syrup, a star actually is a fire. Again, the poem engages our ability to hold two things in the mind at once—just as a metaphor does—only with the poem as a whole, these two things are the literal and symbolic nature of language.

When we use figures of speech in our poetry, we have the opportunity to invite a whole new layer of meaning into the poem.

Poet Mike Dockins and his Favorite Metaphor Exercise

THE FISH TANK OF RAGE

Goal: What we are essentially creating with this exercise are “implied” or “submerged” metaphors, where, in this case, the concrete object is never mentioned explicitly, but only implied by its descriptions.

PREP / MATERIALS

Prepare a whole bunch of little index cards: one pile consisting of concrete details (skyscraper, waterfall, volcano, etc.) and the other of abstractions (fear, loneliness, joy, etc.). Dockins says he uses emotions specifically rather than other abstract concepts such as capitalism or knowledge.

ROUND 1

In this first round, each student gets two index cards, one concrete and one abstract, and the first thing they do is “re-write” the name of their game. So now instead of “The Fishtank of Rage,” they have “The Dagger of Fate” or “The Cocoon of Grief.” At this point, do not worry about all the rules (see below), but, rather, describe the abstraction in terms of the qualities of the concrete object, not the other way around. For example, “A cocoon was sad because somebody died” is getting things backwards. The statement should actually be “Grief is somehow like a cocoon,” and the question for you to answer is, “How so?” How is grief like a cocoon? Well, grief is confined to a small space, but in time can break out of its shell. Something is alive inside of grief. Grief is fragile, etc.

Take just a few minutes and brainstorm as many such short sentences as possible, and then we share a few. Be careful not to over-literalize: “When grief opens up, a moth flies out”— the idea in fact is to create metaphors. So, you should think imaginatively, creatively.

ROUNDS 2, 3, ETC.

In Round 2 and beyond (you can do as many rounds as you like), select new combinations of cards. Complete the steps described in Round 1 with your new words and share your work with each other.

Make sure that you consider *all* aspects of the concrete object. Make sure to not be too inflexible in your thinking — for example, if you only think of the object’s size and shape. Think about how your object changes, and what associations we have with it. For example, a balloon can be a certain color and size and shape, but it can also inflate, deflate, pop, and fly away from you. It can also symbolize celebration, birthdays, hospital visits, etc. Or, a volcano isn’t always erupting. It spends much of its “life” in dormancy, and should give us a feeling of awe of the passage of time. Plus, it can be dangerous but also beautiful.

THE RULES / GUIDELINES, IN SHORT

- Write several separate sentences, as opposed to one long continuous little story.

- Describe the abstraction in terms of the concrete object, not the other way around.

- Do not mention the concrete object directly.

- Do not be overly literal.

- Consider any and all of the object’s qualities and associations.

- You’re essentially creating metaphors, so be creative! Be imaginative! Be profound!

Clichés

One of the reasons why Laura Kasishcke’s poem “Confections” is so successful is because of its originality. When we read about how a star is fire and flower, or how a “baby sleeping’s / a milky sea,” we are taking things in through our senses that we have not before; we are forming new connections between things in our minds. One of the dangers of using figurative language in our writing is relying on clichés, or word packages, that have lost their evocative effect. Rather than startle our senses alive with new connections, clichés roll over us numbly, failing to spark an image in our minds. They are the walking dead of language.

One way to avoid clichés is to not use a phrase if you’ve hear it before. If you’ve heard it in a song, don’t use it. If you’ve heard it on a television show, don’t use it. The following is the first half of common clichés. See if you can complete the phrase:

Cold as__________________________.

Hot as___________________________.

Blind as a _______________________.

Faster than a ______________________.

You are the apple of __________________________.

It’s likely you were able to fill all of these in. Here are the answers:

Cold as ice. Hot as hell. Blind as a bat. Faster than lightning. You are the apple of my eye.

Rather than bringing an image to mind, notice how the words stay distant. They do not succeed in engaging your senses. They have become conceptual instead of sensory. When you have a cliché in your writing, the reader disengages from the poem’s experience. To fix clichés, there are two main remedies:

- Say what you mean. Eliminate the figurative language and be literal, direct. Instead of saying I’m at the end of my rope, say I am frustrated and impatient.

- Rewrite the expression by expanding descriptive language. Instead of He took the bait, explain in detail and images what the bait is and how he took it.

- Freshen up the figurative language by inventing a new metaphor. Instead of quiet as a mouse, why not find something else quiet that reflects the poem’s original subject? Quiet as a pitchfork on Easter morning.

Additional Resources:

For a more complete list of literary and poetic terms, see the following web sites: Burroway, Janet. Writing Fiction. https://guidetonarrativecraft.weebly.com/chapters-1-3.html

and Glossary of Poetry Schools and Movements. The Poetry Foundation. http://www.poetryfoundation.org/learning/glossary-terms?category=schools-and-periods

Adapted from Naming the Unnameable: An Approach to Poetry for New Generations, 2018, by Michelle Bonczek Evory, used according to creative commons CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.