The History of New Mexico

Collapse

Expand

-

Chapter 9: Territorial New Mexico

- Territorial New Mexico

- Civil War in New Mexico

- The Navajo Long Walk

- New Mexico as "Wild West"

- References & Further Reading

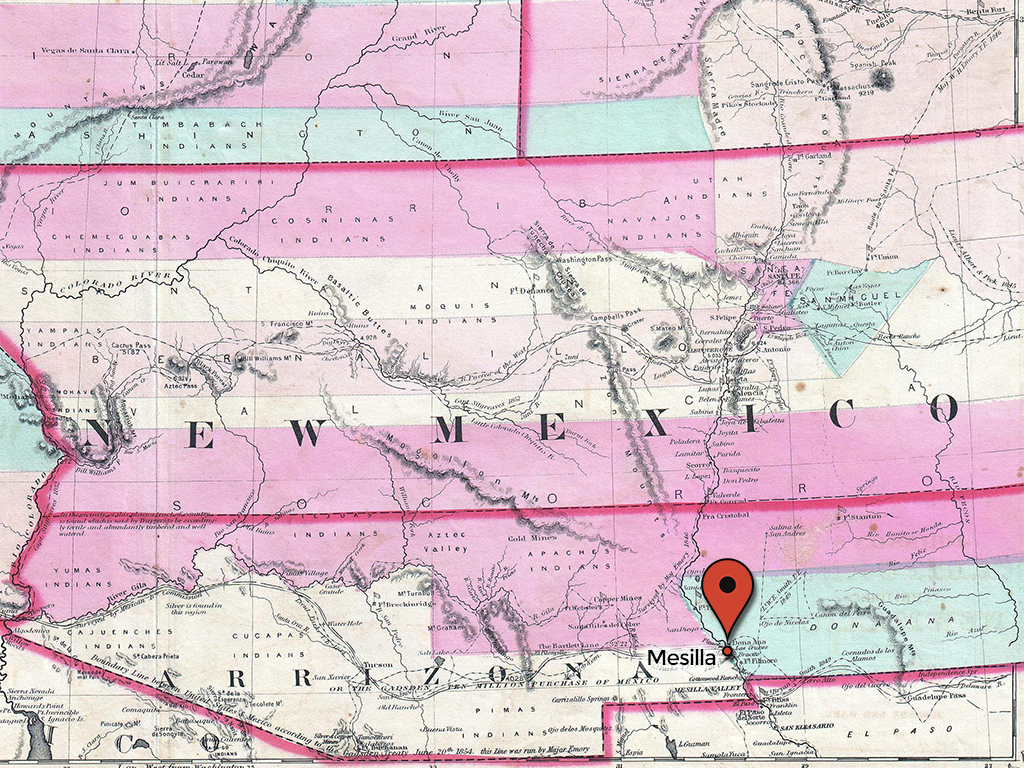

Beginning with the arrival of the Army of the West in 1846, a large military force became a permanent fixture in the territory. At first, the strong military presence was to secure New Mexico as U.S. territory. Between 1848 and 1853 troops remained to guarantee the promise made in Article XI of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that the U.S. military would prevent nomadic peoples from making incursions into Mexico. U.S. military leaders quickly realized, however, Article XI was virtually impossible to enforce. In the negotiations over the Treaty of La Mesilla in 1853, James Gadsden also achieved the annulment of Article XI along with the addition of the Mesilla strip to the United States.

As soon as the Army of the West arrived in New Mexico, Kearny guaranteed nuevomexicanos and Pueblos safety against Navajo, Apache, Ute, and Comanche raids. After 1853, the federal army erected forts and attempted to make good on the promise. Over the next several years, various military commanders and federal Indian Agents came and went. At times the same man filled both posts; at others the offices were separated. Governor John M. Washington, for example, served as both Indian Agent and Military Governor in 1848 and 1849. His first priority was to wage war against the Navajo people in an attempt to settle long-standing conflicts between the Diné and nuevomexicanos.

Washington’s campaign only served to erode dealings between Navajos and American leaders. Following one skirmish in 1849, six Navajos were killed during an attempt to negotiate peace. One was the esteemed headman Narbona who was scalped by a U.S. militiaman. Washington’s successors followed their own distinct policies toward the territory’s indigenous peoples. Some, like Major John Munroe and Lieutenant Colonel Edwin Vose Sumner, considered the barren New Mexico territory to be a waste of American military effort and resources. Others, like Indian Agents James S. Calhoun and Michael Steck, recognized the diversity of peoples and interests in the territory and they forged positive relationships with several bands of Navajos and Apaches.

The lack of a stable and coherent “Indian Policy” at the federal level, however, stoked cultural misunderstandings and conflict. Although several bands of Chiricahua Apaches under the leadership of Mangas Coloradas struck friendly relations with Kearny in 1846, relations quickly eroded. In January 1852, U.S. forces established Fort Webster near the Santa Rita del Cobre mine (near present-day Silver City). Chiricahua warriors saw the new fort as an unsolicited and unwarranted infiltration of their homelands. Despite attempts to solve the conflict through diplomacy, a state of war existed between several Chiricahua headmen and U.S. forces throughout the early 1850s.

In the years immediately following the resolution of the U.S.-Mexico War, new forts sprang up throughout the territory. These included Fort Union on the lands of the Llaneros band of the Jicarilla Apache people, Fort Conrad to the south of Socorro, Fort Fillmore near Mesilla, Fort Stanton among the Mescaleros, and Fort Defiance in the Navajo heartland. The forts suggested Americans’ readiness to use violent force against nomadic peoples, and at times the threat of violence worked at counter purposes to Indian Agents’ overtures. Nearly 4,000 soldiers manned New Mexico’s military outposts by the close of the 1850s.

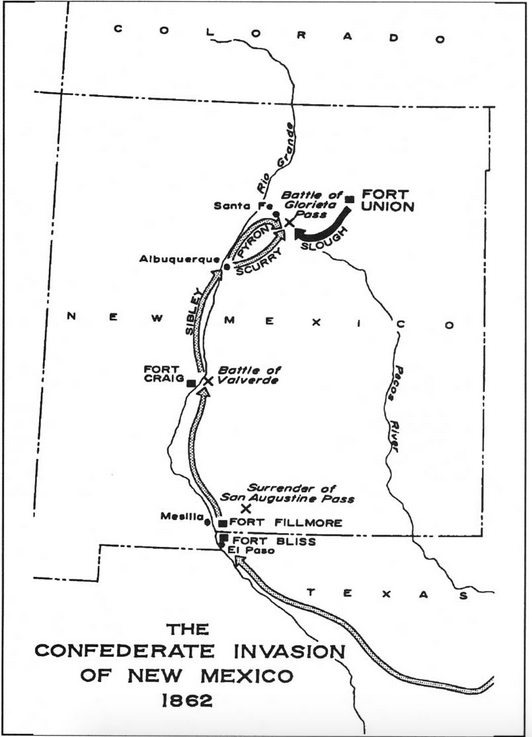

When shots rang out at Fort Sumter in 1861 just over half of the soldiers stationed in the territory left to declare their loyalty to the Confederate cause. Fewer than 2,000 men, under the command of Colonel Edward Richard Sprigg Canby, remained to defend New Mexico in the name of the Union. Fearing a Confederate invasion through the southern part of the territory, Canby directed the bulk of his men and resources to Forts Fillmore, Craig (which replaced Fort Conrad in 1854), and Stanton. Leaders from both sides of the conflict argued that the majority of New Mexicans supported their side. Under the direction of Colonel Henry Hopkins Sibley, Lieutenant Colonel John R. Baylor marched into the Mesilla Valley with 350 men in the fall of 1861. During Confederate control of the area, Mesilla was declared capital of a new territory called Arizona.

During a brief skirmish with Baylor’s troops, Union Major Isaac Lynde abandoned Fort Fillmore and marched northward. Mesilleros certainly were not happy that yet another invading force had occupied their town. Despite Sibley’s hopes to capitalize on disaffection with American control of Mesilla, his actions reaffirmed locals’ fears that his was just another occupying force. In December 1861, he declared martial law, ostensibly to deter “desperadoes, gamblers, &c” that “incited innocent citizens of the valley to rebel against the proper authorities.” [sic]5 His justification, however, suggests that mesilleros considered the Confederate troops as invaders, rather than liberators as Sibley liked to imagine.

Produced by Trillium Productions, LLC. Keith Dadley, Graphic Artist & Arizona Historical Society/Tucson, G4300 1863.J6.

The Confederate leadership in southern New Mexico prohibited the enlistment of Mexican-heritage people except to fight against Apaches. Similarly, Colonel Canby declared that nuevomexicanos not join Union ranks because they carried “no affections for institutions of the United States.”6 Yet, following the shock of Baylor’s victory in Mesilla, pragmatism pushed Canby to encourage nuevomexicanos to join his forces. Despite the need, convincing nuevomexicanos to sign up was easier said than done. Many of them, like the mesilleros, felt ambivalence toward U.S. citizenship.

Governor Henry Connelly, a Lincoln appointee, stepped in to help by reframing the conflict in regional terms. Rather than speak of patriotism or the chasm between North and South, he instead cast the struggle as one between Texans and nuevomexicanos. Due to earlier events like the 1841 Texan-Santa Fe Expedition, nuevomexicanos held deep animosities toward Texans. As Connelly recognized, many nuevomexicanos had associated the concept of American identity with the hated image of the Texan. As historian Anthony Mora has demonstrated, “Texan identity often implied a racial meaning for Mexicans”—including nuevomexicanos.7 Although nuevomexicano enrollment was never as widespread as Canby had hoped, the revision of the conflict’s significance persuaded many to join his ranks.

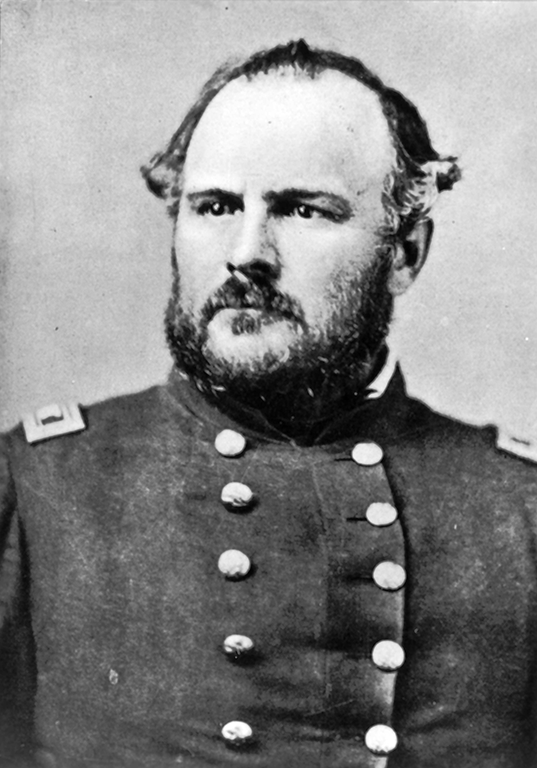

Courtesy of Robert M. Utley

Canby decided to concentrate his men at Fort Craig in an effort to hold off an anticipated Confederate advance northward toward Santa Fe. He was correct that Sibley was planning a new offensive. The Confederate general had served with the U.S. army in Taos prior to the outbreak of the Civil War. Due to his time in the territory, Sibley was able to convince Confederate President Jefferson Davis of the value of a New Mexico campaign. The Confederacy desperately hoped for a transcontinental rail connection to the Pacific to counter the rail supremacy of the North. Additionally, California offered the promise of gold and a silver lode had recently been unearthed in Colorado. New Mexico promised to be the ticket to all of that potential wealth.

As fate had it, however, such was not to be. In part, Sibley was not the man for the job (his own men considered him to be pretentious and overly preoccupied with luxury), and the concerted effort of Union forces—with or without nuevomexicano support—proved too much for his attempt to conquer New Mexico. Still, at first Sibley’s forces seemed to have the upper hand. At the Battle of Valverde in February 1862 they battled Canby’s forces to a draw. Canby refused to surrender Fort Craig and, rather than press the issue, Sibley bypassed it and continued northward to Albuquerque and Santa Fe. Both proved to be easy targets for the Confederate army.

Courtesy of Pecos National Historical Park

The situation for the Union seemed dire until reinforcements from Colorado arrived. Colonel John P. Slough led 1,300 Colorado Volunteers toward Santa Fe from Fort Union and engaged Sibley’s forces at the Battle of Glorieta Pass, about twenty miles southeast of Santa Fe. The three-day battle is remembered as the “Gettysburg of the West.”8 Between March 26 and 28, 1862, about one-thousand Confederate soldiers under the command of Colonel William R. Scurry clashed in an intense and bloody conflict. At the end of the first day, Slough’s men retreated and Scurry believed that the Union offensive was over.

Courtesy of The Denver Public Library, Western History Collection

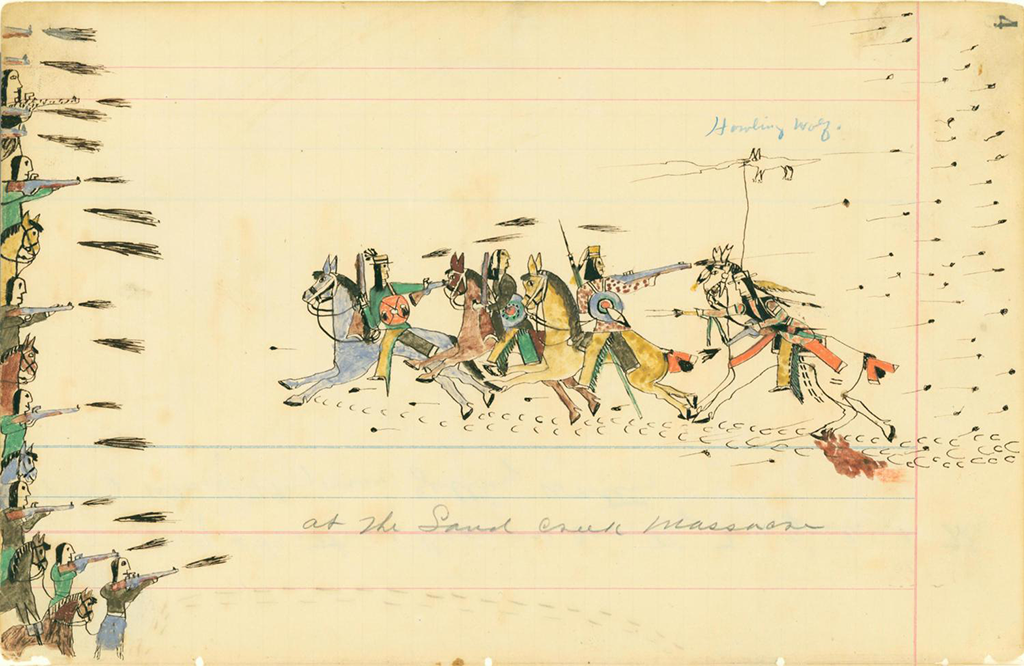

Scurry, however, was unaware of the movements of four hundred Union forces under Major John M. Chivington, a Methodist minister from Denver who later enacted the infamous Sand Creek Massacre. With Lieutenant Major Manuel Chávez of the First New Mexico Volunteers as a guide, Chivington’s party marched for five hours in an attempt to flank enemy forces. In the process, the group accidentally happened upon the Confederate supply train. Following a short skirmish, Chivington’s men captured the provisions, which included eighty well-stocked wagons and nearly five-hundred horses. Due to the loss, Scurry retreated to Santa Fe and, having lost one-third of his troops and the bulk of his supplies, Sibley had no choice other than to abandon New Mexico. His men marched southward and returned to Texas.

Courtesy of Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College

Although Glorieta Pass marked the effective end of the Confederate invasion of New Mexico, Confederate troops remained in Mesilla until July 1862 when news of an impending Union attack spurred their retreat to Texas. On August 15, 1862, ten companies of the First California Infantry, under the command of General James H. Carleton, arrived in the Mesilla Valley. Despite mesilleros’ and other nuevomexicanos’ general feeling of support for the Union, once again the California Infantry represented another occupying force. Over the next year, the troops sapped local resources at the expense of locals. In response, some mesilleros relocated south to towns in northern Chihuahua. Most, however, stuck it out.

By the late 1862 the Confederate threat to New Mexico had ended. Union forces continued to maintain a strong presence in the territory in order to prevent another attempt to take it. Many nuevomexicanos, such as Manuel Chávez, distinguished themselves and asserted their loyalty to the United States through military service during the conflict. Despite their sacrifices, however, full citizenship rights in the Union were not their reward. New Mexico continued to be governed by presidential appointees from far outside the region and local nuevomexicanos struggled to maintain a voice in territorial policy making. In the northern part of the territory, hispanos resolved to further emphasize their American identities in an effort to gain a coveted place among the other states. People in southern New Mexican towns like Mesilla, however, harbored stronger resentment and emphasized ties across the border to Mexico.