The History of New Mexico

Collapse

Expand

-

Chapter 10: Americanizing & Modernizing Ethnic Identities

- Americanizing & Modernizing Ethnic Identities

- "Apache Wars" & The Border

- Creating The Land of Enchantment

- Spanish-American Ethnic Identity

- References & Further Reading

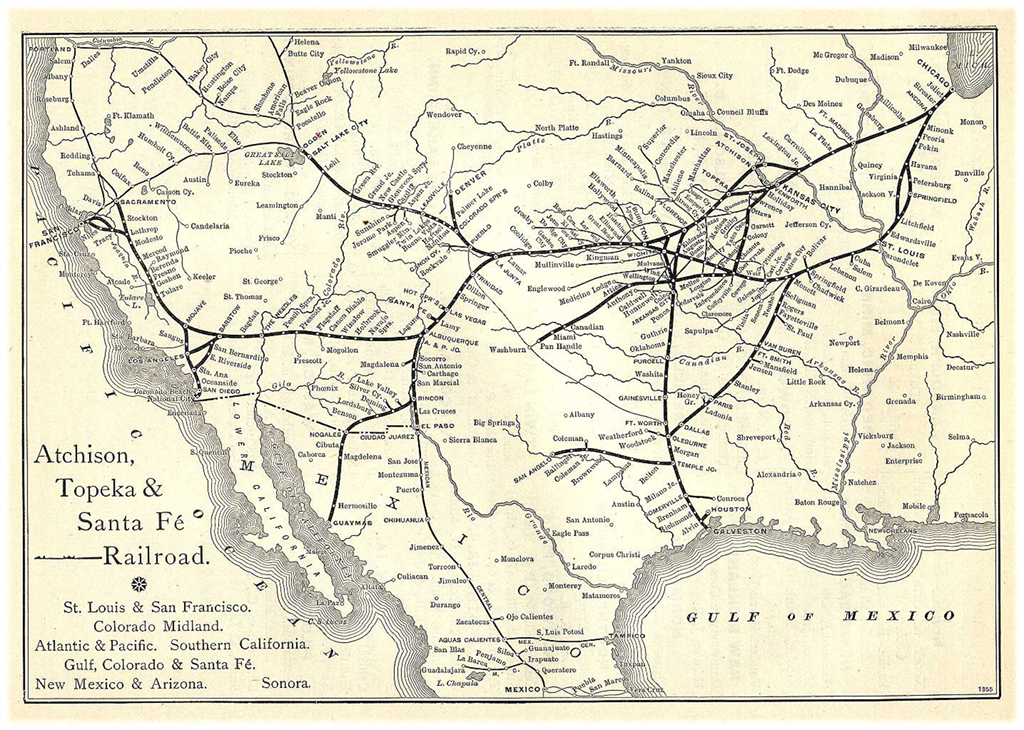

Despite the notion that New Mexico had effectively been secured for capitalist development through the dispossession of Apaches and Navajos, boosters commonly met with disappointment in the years between 1880 and 1920. Many of the people who came to New Mexico from the eastern United States did so in order to recuperate from tuberculosis—not because of the promise of economic opportunity in the territory. The Civil War had emphasized the value of railroads, but it was not until 1879 that the Atchison, Topeka, & Santa Fe Railroad (later known as the Santa Fe Railroad) entered New Mexico.

Over a decade earlier, in 1862 the Union government had passed the Pacific Railroad Act, which was expressly designed to establish a transcontinental rail route, roughly along the Oregon Trail. In the years leading up to the Civil War, the future transcontinental rail line captured the imaginations of people throughout the nation. There was a virtual contest between New Orleans, St. Louis, and Chicago for the eastern terminus of the transcontinental route. Once the Civil War began, Chicago won the day because northern industry provided financial backing for rail construction that simply did not exist in the South.

Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 143091

Despite a lack of resources for railroads, Southern politicians had long dreamed of completing a transcontinental line to benefit trade in their region. The 1853 Gadsden Purchase was made in part to provide a route for a transcontinental line that connected to New Orleans. By the mid-1870s, the Southern Pacific Company made good on that vision with a line between New Orleans and Los Angeles. In general, railroads made their mark on the Western United States due to the terms of the Railroad Act that provided large swaths of land to companies willing to construct rail conduits into the West.

As historian Robert H. Wiebe suggested, prior to the creation of railroads the United States was a disconnected nation of “island communities.”16 Seemingly overnight, rail lines promised to shorten time and space by making travel rapid and efficient between points across the country. New interconnectivity impacted daily life in numerous ways. Prior to railroads, few people traveled beyond their home communities. Items sold at local mercantile stores were expensive due to lack of stable transportation networks. Railroads improved prices and made it possible for more people to travel beyond their hometowns.

Courtesy of Pam Rietsch, MARDOS Memorial On Line Library/Wikimedia Commons

Print culture expanded with railroads as well. Individual families generally had a copy of the bible, but few other books. Such was especially the case in outlying rural areas where magazines, newspapers, and books were hard to come by. As new rail lines extended into the rural West, telegraph lines followed the tracks. By the early 1880s, Associated Press dispatches meant that people in places as distant from one another as Springer, New Mexico, and Chicago, Illinois, read the same accounts of national and international events. Local newspapers thrived, especially in places like New Mexico where a strong Spanish-language press had long existed.

Railroads also improved mail delivery, which had never been especially reliable. Along with bringing down the cost of sending mail, companies like Montgomery Ward and Sears, Roebuck, & Co. profited by circulating mail order catalogs. These allowed people to purchase goods, including cloth, irons, sewing machines, magic lanterns, and some groceries, far more cheaply than had previously been the case. Railroads thus helped to create a national market that altered local cultures.

Heightened ability to travel gave rise to the tourism industry which quickly became an integral component of New Mexico’s economy. National trends began to impact local consumption habits, and there was a shift from smaller-scale merchant capitalism to larger-scale industrial capitalism. Corporations began to push aside community mercantile agencies due to their ability to sell goods more cheaply. Despite such innovations, however, regional cultures persisted in places like New Mexico where unique languages and traditions defined the ways in which people interpreted national trends.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

The first transcontinental connection came when the Union and Central Pacific lines met at Promontory Point, Utah (north of Ogden) in 1869. After that, it seemed every town in the West hoped to draw the railroad toward it. In 1880, the Southern Pacific line was completed. Ironically, the Santa Fe Railroad bypassed its namesake at the territorial capital, although a spur line was added between Lamy Junction and Santa Fe a few years later. In part, the engineers hoped to avoid the La Bajada pass. In terms of territorial politics, the Santa Fe Railroad Company hoped to avoid subjugation to the powerful Santa Fe Ring by building around the capital.

The Santa Fe and Southern Pacific were the two rail companies that made the most indelible mark on New Mexico. Since the close of the U.S.-Mexico War, however, many Americans had considered New Mexico a place to get through—not a destination. Expansionists’ goal had been to acquire California. New Mexico just happened to come along with it. By the 1880s, the primary goal of the Santa Fe and Southern Pacific rail companies was to transform New Mexico and the larger Southwest into tourist destinations.

The two different lines marketed distinct, romanticized images of New Mexico. The Santa Fe Railroad portrayed the area as dominated by red rock and adobe architecture, while the Southern Pacific promoted desert landscapes and Spanish missions. Both companies had been running trains through the territory for about a decade when the nationwide Panic of 1893 set in. The Santa Fe Railroad Company filed for bankruptcy as a result, and the Southern Pacific focused on passenger travel between New Orleans and Los Angeles in an effort to rebound financially.

Following the bankruptcy, the new president of the Santa Fe Railroad recognized the need to transform the route through New Mexico into a touring line in order to help the company become profitable. The transformation from a shipping route to a touring route, however, was not as simple as placing different cars on the line. The public image of New Mexico Territory had to be altered. Corporate advertisers made the decision to promote the region as “Colorful Southwest Indian Country,” and New Mexico itself as the “Land of Enchantment.”17

Artists and indigenous peoples played a central role in the campaign to repackage the territory. As scholars of tourism have pointed out, places targeted by the industry are transformed in order to present visitors with the types of images and experiences that they expect to find. With the expansion of the capitalist economy into New Mexico, especially with the arrival of the railroad, indigenous peoples and rural nuevomexicanos sought out new means of making money to support themselves and their families. In order to do so, many of them took jobs with the Santa Fe Railroad, and Anglo entrepreneurs trained them as cultural performers to appeal to the sensibilities of tourists that arrived at the depots in places like Las Vegas and Albuquerque.

In striking juxtaposition with the Apache Wars, Santa Fe Railroad magnates thus decided to make Native Americans themselves the destination for tourists to New Mexico. The ostensibly ancient lifeways of Navajos, Pueblos, and even nuevomexicanos resonated with a growing group of well-to-do Easterners who had become frustrated and disillusioned with the excesses of modern life. By taking a trip along the Santa Fe line, they were promised a journey into the past in which they would be greeted by people who had avoided such urban problems as pollution, overcrowding, poverty, and violence.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

Travel literature emphasized the exoticism of New Mexico and the Southwest. Wealthy Americans had read about the experiences of their European peers who traveled to the Middle East or to Egypt to tour lands and see peoples that still seemed marked by antiquity. Ironically, the tourists interpreted and reported on ways of life that were not their own without considering the perspective of the inhabitants of the lands they traversed. In an effort to build on the popularity of Middle Eastern travel narratives, American boosters began to argue that U.S. tourists “See America First.”

In New Mexico this type of impulse resulted in an advertising campaign that touted Navajos as the “Bedouins of North America.” Such imagery underscored the nomadic lifeways of the Diné people, while overlooking elements of their lives that might be considered more modern, such as their agricultural production. The argument was that tourists need not travel across the Atlantic to find the wonders of antiquity; remnants of the pre-modern past were alive and well in New Mexico.

Although far less violent than the military campaigns that had targeted New Mexico’s indigenous peoples, the tourism industry became profitable by taking advantage of native customs and lifeways. In certain respects, native participants in heritage tourism found a way to support themselves economically while simultaneously preserving elements of their cultures. In other ways, they were forced to adhere to Anglo American characterizations of their traditions.

Courtesy of KansasMemory.org, Kansas State Historical Society

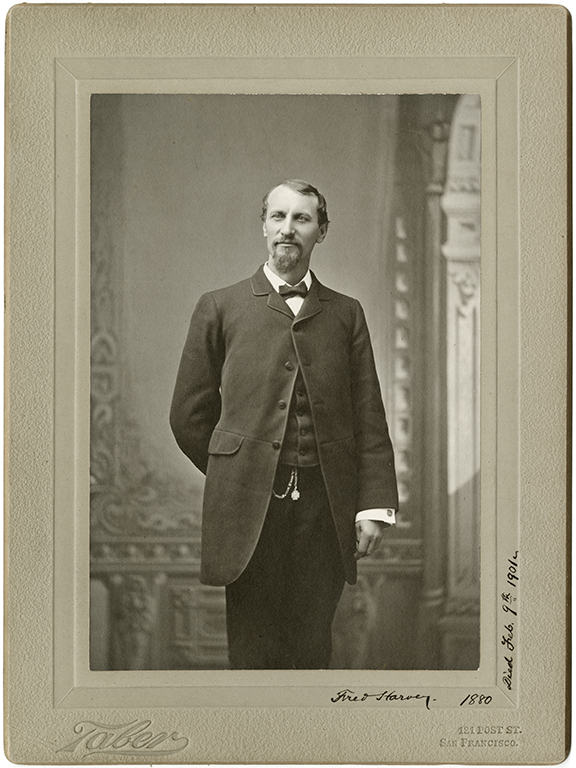

The person that was most clearly associated with remaking New Mexico for tourism was Fred Harvey. Harvey was born in London in 1835, and he immigrated to the United States at age fifteen in 1850. In New York City he labored as a busboy and dishwasher in order to get on his feet. He worked in several other restaurant jobs before moving to New Orleans and then St. Louis. Eventually he secured a position as a mail clerk for the Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy Railroad. He realized a great need for lodging and concessions along the railroads, and although he pitched his ideas to his bosses at the Burlington Railroad, it was Santa Fe Railroad president Charles F. Morse that agreed to give him his first break.

In 1876, with Morse’s approval, Harvey opened his first dining room at the Topeka depot on the Santa Fe line. Over the next twenty-five years, he built the country’s first major chain organization. When he died in 1901, the Fred Harvey Company consisted of fifteen hotels, forty-seven restaurants, and thirty dining cars. His son Ford continued the operation after his father’s death from the company’s Kansas City, Missouri, headquarters.

Harvey was most famous for his Harvey Houses, which were either stand-alone dining establishments or combination restaurant and hotel establishments along the Santa Fe Railroad. Several of them were in New Mexico and Arizona territories. His New Mexico locations included the La Fonda Hotel off the plaza in Santa Fe, the Ortiz Hotel in Lamy, the Alvarado Hotel in Albuquerque, and the Castañeda Hotel in Las Vegas, as well as lunchrooms in Las Vegas, Lamy, Albuquerque, Gallup, Belen, and Deming.

During his life, Harvey became one of the most prominent boosters of New Mexico and the Southwest at the national level. The Santa Fe Railroad was his partner in the creation of a romanticized Native American image for the region. In their repackaged rendition, Native peoples represented two sides of the same coin: modernity mixed with ancient traditions. As was the case for boosters and reformers around the turn of the twentieth century, despite idealized admiration for what they perceived as New Mexicans’ pre-modern lifeways, the outsiders never wanted to give up the modern world completely. When push came to shove, they tended to favor the modern over the traditional. Indeed, the Santa Fe Railroad illustrated this tension by naming its newest locomotives things like “Super Chief.”

The Grand Canyon became one of Fred Harvey’s main attractions and all of the other elements of his enterprise revolved around it. The Santa Fe Railroad hired architect Mary Colter to design Hopi House, a building that resembled the actual Hopi village of Old Oribi. Colter employed a crew of Hopis to aid in construction and give the building the look and feel of authenticity. Inside, Colter designed a Harvey House hotel and lunchroom meant to appear as if they had been taken straight off of First Mesa. Of course, the structure also boasted all of the modern amenities that tourists had come to expect.

Construction efforts included prehistoric-looking watchtowers set up at intervals along the Grand Canyon’s rim, suggesting that Native peoples had always used them to gaze upon the canyon’s expanses. The reality was that they were made to seem that way in order to appeal to tourists. The Santa Fe Railroad and Fred Harvey Company employed Hopi people to live at Hopi House, where they also publicly practiced their trades of weaving and pottery. Tourists paid for the opportunity to witness them at their craft, and had the chance to purchase Hopi wares in the gift shop.

Hopi people did not historically inhabit the Grand Canyon itself, but company promoters considered them to be more “picturesque” than the Havasupai people whose homeland included the canyon. Havasupai men and women did get jobs and at the new tourist sites, but their work was typically done behind the scenes as janitors and maintenance laborers.

Courtesy of Gaylon Emerzian

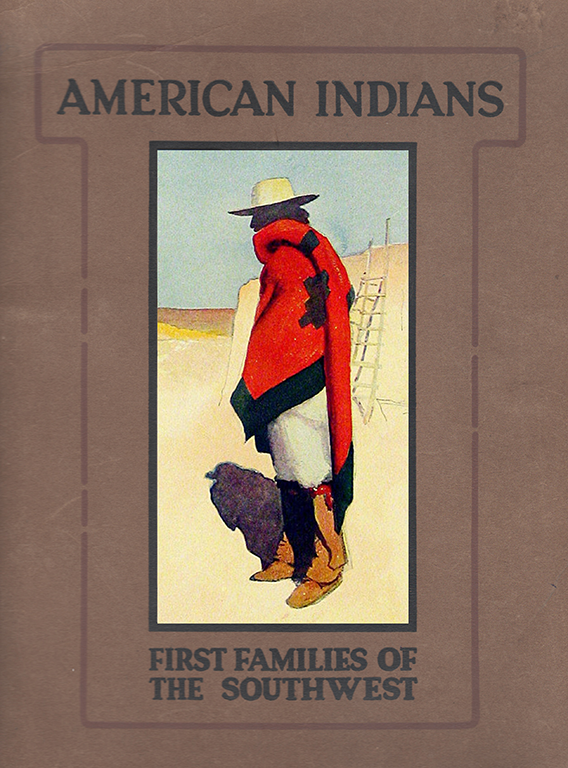

As is the case in the tourist industry, the Land of Enchantment created in New Mexico and Arizona by the Santa Fe Railroad was highly selective. Native peoples were presented to tourists in ways that would appeal to their tastes and sensibilities. And the railroad and Fred Harvey Company made a great deal of money in the process. A Fred Harvey Company pamphlet, titled “American Indians: First Families of the Southwest,” was published in 1920 to illustrate the idea that Native families were essentially the same as Anglo American families in terms of gender roles, parent-child relationships, and family activities (including work and play). The reality, however, was that many Native peoples traditionally observed gender roles that assigned women to positions of power and influence. Many Pueblos were and are matrilineal.

The emphasis on the proper role of “respectable” white women was also a major factor in the Harvey Company’s business model in the form of the Harvey Girls. Fred Harvey worked hard to create an elegant atmosphere in his restaurants, complete with all the markers of Eastern and Midwestern dining respectability, including fine china, linens, silver, and flowers on each table. Young, white, single women worked as servers in this environment. The first Harvey Girls were hired to work at the Raton, New Mexico, Harvey House in 1883.

Courtesy of Northern Arizona University, Cline Library

Newspapers throughout the Midwest and Eastern United States ran advertisements that sought “young women 18 to 30 years of age, of good character, attractive and intelligent, as waitresses in Harvey Eating Houses in the West.”18 Over 100,000 young ladies left their homes to seek out opportunity in a time that offered very few prospects for women in the workplace. The Harvey Company paid $17.50 per month—a generous wage for women in the late nineteenth century. In order to stabilize the labor force, Harvey Girls agreed to remain single for a period of at least one year after their date of hire. Despite that provision, many of them married when they got the chance. Following a period of intense training, the new employees were sent to a dormitory near their place of work. A matron presided over each home to maintain a set of strict rules that were intended to promote high moral standards among the women.

In their trademark black dresses and white aprons, Harvey Girls contrasted with the women of the red light districts of many Western cities and towns. The girls quickly became shorthand for the reputation of the Fred Harvey Company. By contrast, African American or Hispanic women worked behind the scenes as cooks, dishwashers, and maids. Along the Santa Fe Railroad and in Fred Harvey restaurants and hotels, complex notions of race and gender organized labor and promoted New Mexico and the Southwest to the rest of the nation.

Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 053568

Famously, the city of Santa Fe took cues from the success of the Santa Fe Railroad and Fred Harvey Company to remake its own image. Between the 1880s and the 1920s, Santa Fe boosters and politicians hired a series of architects, photographers, and anthropologists to create a unique style for the municipality that drew on Pueblo and Spanish-colonial era architectural designs. In the construction of the La Fonda Hotel the visions of city fathers and railroad magnates dovetailed. Although the building at the current hotel site on the edge of the Santa Fe Plaza was an inn during Spanish Colonial times, the current structure was erected in 1922 in the newly devised Pueblo Revival Style architecture. The Fred Harvey Company was once again on the leading edge of cultural tourism, and Santa Fe, touting itself as “the city different,” was one of the first culturally reimagined cities in the nation.