The History of New Mexico

Collapse

Expand

-

Chapter 13: The Great Depression & The New Deal

- The Great Depression & The New Deal

- Artist Colonies & Rural Reformers

- Depression Comes to New Mexico

- Dennis Chávez & The Hispanic New Deal

- Indian New Deal & Navajos

- References & Further Reading

During his campaign for the presidency in 1932, Franklin D. Roosevelt promised that he would provide a New Deal for the American People. Once he took office in March of 1933, his campaign promise began to take shape in the form of a bank holiday and a slate of new legislation designed to improve the U.S. economy. Roosevelt’s program, called the New Deal, included job creation programs and spending initiatives. In an effort to find creative solutions to the nation’s grave economic problems, the New Deal created an “alphabet soup” of agencies known by their acronyms. The CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps), NYA (National Youth Administration), and WPA (Works Progress Administration, renamed the Works Projects Administration in 1939) are just a few examples.

Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration

In the landslide election that brought Roosevelt into office, many other Democrats also received the support of their local constituencies. New Mexico was no exception. The Depression era broke the long dominance of the Republican Party on state politics. Representative, then Senator, Dennis Chávez rose to prominence as a strong supporter of the New Deal who had a knack for bringing its benefits to New Mexico’s people.

Chávez was one of New Mexico’s native sons. He was born Dionisio Chávez on April 8, 1888, in rural Valencia County. After completing the eighth grade, he dropped out of school to support his family economically as a grocery delivery boy. Despite his lack of formal education, Chávez always loved history and had an intense interest in politics. In that regard, he followed in the footsteps of his father who was active in the local Republican Party. Although he gained his father’s affinity for politics, when he made his own career Chávez did so as a Democrat.

As he worked his delivery job, he also found time to read extensively and to attend night school. When he was seventeen years old, he was hired to work at the Albuquerque engineering department and he moved to the city. In Albuquerque, Chávez participated in the local movement for statehood and after an unsuccessful campaign for the county clerk’s office, he earned a position with Democratic Senator Andreius A. Jones’ staff in Washington, D.C. While there, he attended Georgetown Law School.

Upon his return to Albuquerque he established a law office and once again set his sights on state politics. During the 1920s, he served in the state legislature and in 1930 he won election to the U.S. House of Representatives. In the 1934 election, he unsuccessfully challenged Republican Senator Bronson Cutting. Following his narrow loss, Chávez alleged that Cutting had committed voter fraud. As he returned from Washington to address the charges, Cutting was killed in a plane crash. Governor Tingley subsequently appointed Chávez to fill the senate seat vacated by Cutting’s tragic death.

As historian María E. Montoya has recounted, Dennis Chávez was snubbed by his Senate colleagues on his first day of service in Washington. When Vice President John Nance Garner called on Chávez to receive the oath of office, Oregon Senator Charles I. McNary raised the issue that a full quorum was not present. The objection seemed strange because the chamber was full; accordingly, the vice president proceeded with the oath. During roll call, however, six senators stood and turned their backs on Chávez as he walked to the front of the room and they then left the chamber.

Montoya has pointed out that the senators’ treatment of Chávez may have been based on any combination of several factors. They may have disapproved of the way he had benefited from the death of their former associate. Their protest may have also been a signal that they believed a Mexican American was unfit for service in the elite congressional body.

Interestingly, the story was only mentioned briefly in Chávez’s personal papers, not in the Congressional Record. Whether or not it is entirely based on fact, the story has been retold as an emblematic example of “how poorly New Mexicans, particularly Mexican Americans and Native American citizens, had been treated by the federal government and eastern lawmakers.” Indeed, Chávez himself once quipped, “If they [Mexican Americans] go to war, they’re Americans; if they run for office, they’re Spanish Americans; but if they’re looking for a job, they’re damned Mexicans.”13

Between 1934 and 1962, when he died of cancer, Chávez overcame such preconceived notions to build a strong reputation for New Mexico and its people in the Senate. As an advocate for New Mexico’s hispano population, he constructed what has been referred to as the Hispanic New Deal—a specific subset of policies and programs that were geared toward nuevomexicanos. Chávez understood the need for New Mexico’s people to gain education and experience in modern vocations that would allow them to increase their skills and provide for their communities long after the depression.

Still, much of the Hispanic New Deal funding was channeled into the types of programs that earlier reformers hoped to enact to preserve their notions of the pre-industrial New Mexican village. Agencies like the CCC, WPA, and NYA were not unique to New Mexico, but they were adapted to the specific needs of nuevomexicanos, at least from the perspective of program administrators. Often times, nuevomexicanos, and even Senator Chávez, realized that New Mexicans’ needs were unfulfilled by New Deal agencies.

Senator Chávez, state legislators, and reformers made a concerted effort to keep young nuevomexicano men in CCC camps within the state in order to keep potential conflicts and discrimination to a minimum. The CCC employed men between the ages of 18 and 25 on conservation projects. CCC enrollees built trails and facilities in National Forests and National Parks, participated in soil conservation projects, worked with the grazing service, and aided in the construction of dams under the purview of the national Bureau of Reclamation.

CCC camps were organized following the pattern of the U.S. military. Participants slept in barracks and were expected to go to bed and wake up at specified times. They did not typically run military-style drills, but they were organized into regimented groups to complete their work. Each enrollee received $30 per month, but they only received $5 of that amount for personal use. The other $25 went to their families, enabling many to withdraw from relief rolls.

Educational opportunities were often provided in CCC camps to combat illiteracy, promote vocational skills, and, in New Mexico, to promote nuevomexicano customs. Each camp had an educational advisor, and teachers came from nearby public schools or from among the enrollees themselves. The educational experience varied greatly from camp to camp. At the Redlands, New Mexico, camp, enrollees formed their own school where they shared whatever skills and knowledge they had with one another. The camp near Las Cruces offered high school diplomas, and the educational program associated with the camp at Santa Fe later became a trade school. Classes were typically held in the evenings once the work day had ended, and participation was voluntary. Many enrollees took advantage of the training, and attendance was often as high as seventy percent.

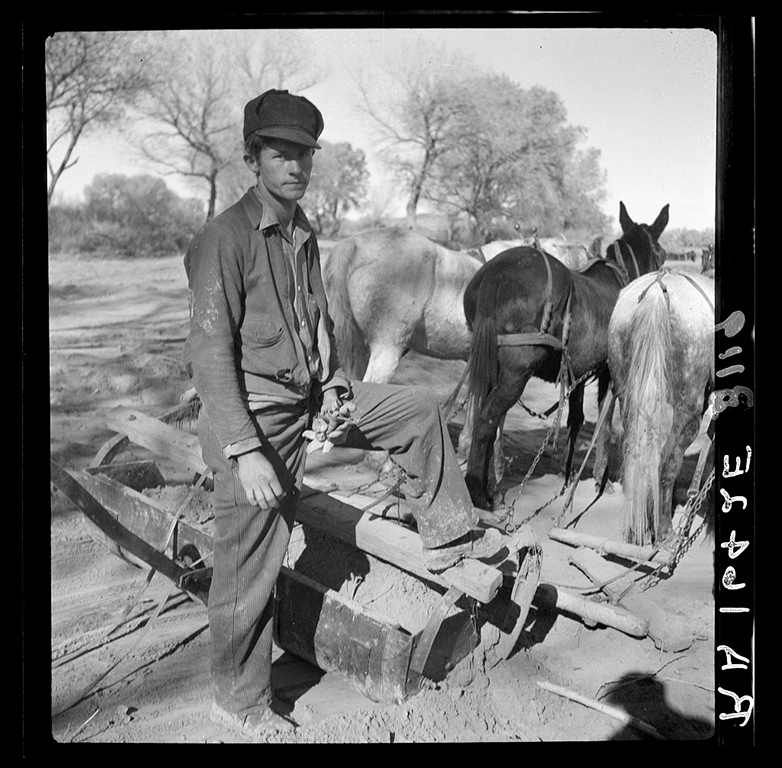

One of the tasks that CCC enrollees performed in New Mexico was to instruct nuevomexicano farmers in modern methods of soil conservation, including the practice of terracing and contour plowing. Because the camps in northern New Mexico tended to be between ninety and ninety-five percent hispano, young nuevomexicanos were the ones to work with other hispanos on farming techniques. Although there were some conflicts in the nuevomexicano-dominated CCC camps, they were relatively free from racial tensions.

Such was not the case in southern New Mexico’s integrated camps. Out-of-state Anglo American CCC enrollees complained that they had to share tents with “greasers.” On one occasion a boxing match turned into a riot and an Anglo enrollee was beaten to death in the melee. In Chaves County, enrollees levied complaints that they had not received the pay that was due to them. They also charged that medical facilities were lacking, theft and fighting were commonplace among enrollees, and that nuevomexicanos experienced racial discrimination from Texan and eastern New Mexican Anglo enrollees. Anglo Americans were reportedly upset “when the native New Mexicans spoke in Spanish among themselves.”14

Those nuevomexicanos who worked in CCC camps outside of New Mexico tended to be more vocal about discrimination than other hispano-American enrollees. At the camp in Duncan, Arizona, a group of “Spanish-speaking boys” from New Mexico reported that they had been denied underwear and harassed by camp officers. They sent their grievance to the national CCC director in Washington, D.C., who subsequently ordered an investigation. When other hispanos in the camp declared that they were “extremely satisfied” with conditions there, the investigator concluded that the nuevomexicanos were “unduly sensitive.”15

Historian Suzanne Forrest has shown, however, that nuevomexicanos were more likely to report discrimination than their hispano counterparts from other parts of the country due to their long tradition of political participation. Unlike political officials in Texas or California, New Mexican officials clearly understood the need to work with the state’s nuevomexicano majority. New Mexico hispanos saw the political system as a possible avenue to redress their problems—including discrimination—whereas other hispanos often did not.

As was the case throughout the United States, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) oversaw a number of programs that created work for New Mexican artisans, writers, educators, and artists. WPA projects included cultural initiatives to catalog and preserve oral histories from people of various backgrounds across the state. They also provided funds to improve infrastructure in New Mexico’s cities and towns, including works of art in public spaces. In concert with the Emergency Education Act (EEA), the WPA funded salaries for teachers. The programs also provided money for the construction of schools in rural areas. In northern New Mexico, as had been common since the Spanish colonial era, women often worked as plasterers on the school-houses.

Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 155221.

The unique drive of the Hispanic New Deal focused education efforts on literacy and traditional craft production to a greater extent than on vocational programs, despite Senator Chávez’s efforts to reverse that trend. Such programs emphasized the production of items like santero artwork, woven goods, and furniture. Along with reviving the creation of hispano and Native American craft goods, WPA agents taught New Mexicans how to market their items and support themselves.

The small town of Chupadero stood as a case study in the success of such programs. Unfortunately, it was the exception rather than the rule. With the help of rural education teams, residents who had formerly transported wood on burros for sale in Santa Fe produced rawhide and wood furniture, as well as saddles and harnesses. The sale of such goods allowed nearly all of the small town’s families to end their reliance on the relief rolls and support themselves economically by the end of 1933.

Similarly, residents of Taos successfully turned craft production into a successful economic venture. The town’s first vocational school opened its doors in September of 1933 and paved the way for the creation and sale of hispano and Pueblo craft items. There, Brice Sewell, supervisor of Industrial Education and Rehabilitation for the State of New Mexico, devised programs with a very narrow focus and purpose. In order for Taos hispanos’ products to compete with machine-produced goods, he believed their crafts needed to be both aesthetically pleasing and long lasting. They also had to appear authentic to appeal to tourists. Although Sewell truly believed that craft production would alleviate northern New Mexico’s economic woes, Forrest has also illustrated that his programs “also severely limited their options.”16 In other states, vocational programs also included training in trades such as auto mechanics and welding, as well as education in finance and commerce.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

Literacy programs made a marked impact in the lives of nuevomexicanos in rural areas throughout the northern part of the state. In Nambé, a 78-year old man (he remained anonymous in the WPA study) who had never previously had any formal schooling remarked, “We viejos (elderly) in this class tonight, we have a chance which we never had before . . . to learn things which we have needed for so long.”17 At the same community meeting, another elderly community member who remained illiterate encouraged those present to take advantage of the programs that were offered to them so that they could create a brighter future for their descendants.

New Deal educational initiatives also included women’s work programs, designed to pick up where underfunded cultural initiatives of the 19-teens and 1920s had left off. County Home Demonstration Agents, who were typically Anglo American women, traveled to rural villages to help nuevomexicanas modernize their means of food preservation, child rearing, hygiene, and sewing practices.

As had been the case in 1920s efforts to assimilate immigrant women, such programs highlighted the tension between reformers’ desire to preserve the perceived purity of native cultural practices and their drive to improve elements of hispano culture that they deemed outdated. Indeed, one of the central aims of an initiative in 1940 that specifically focused on women who had just given birth was to overcome “native superstitions” associated with birth. Health administrators wanted to end the “fear attached to bathing a mother during the first forty days after childbirth or exposing them to fresh air and sunshine.”18

WPA Federal Writers and Civil Works of Art projects served the dual purpose of providing work to writers and artists while simultaneously preserving regional histories and art techniques. Many of the writers employed by the WPA were Anglos who traveled across New Mexico to meet with hispanos, Pueblos, and Navajos of various social and economic backgrounds to record their oral histories. Due to language barriers, nuevomexicano writers also found jobs as interpreters with the project which produced a plethora of documentation on the state’s folklore and history, primarily in English and Spanish.

One of the most widely remembered aspects of the Federal Writers Project was the American Guide Series. Writers in every state produced a guidebook that described each city and town, as well as essays that described local history, sites of interest, and a series of photographs. The Federal Writers Project was most active between 1936 and 1940, and manuscripts based on its interviews are scattered throughout New Mexico’s various archives, including the Center for Southwest Research at the University of New Mexico, the State Records Center and Archives, and the Fray Angélico Chávez Library in the Palace of the Governors. A large portion of the manuscripts have been digitized through the U.S. Library of Congress.

Likewise, local artists of all ethnic backgrounds were commissioned under the auspices of the WPA Public Works of Art project to create paintings and sculptures that reflected local styles. Musicians also compiled traditional songs and dances for historical preservation.

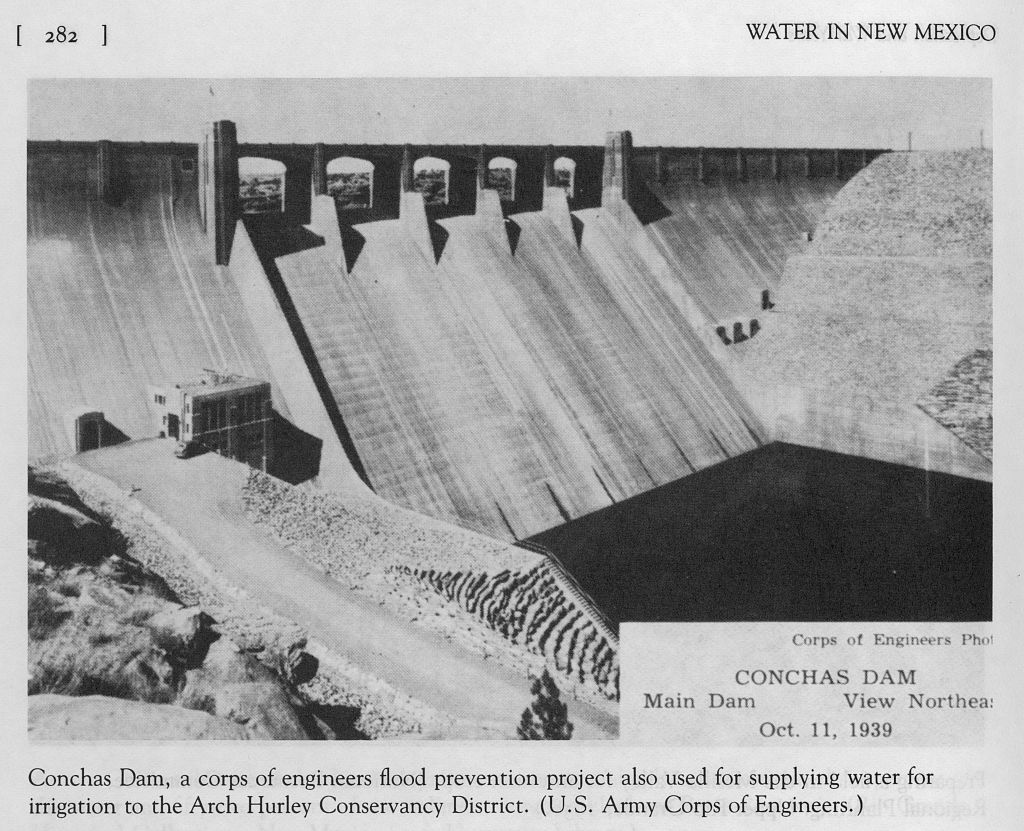

Many of the New Deal projects that most impacted New Mexico came to the state in the form that they did through the efforts of Senator Dennis Chávez. He worked tirelessly to bring federal dollars to the state in the 1930s, and he focused his attention on projects that would allow nuevomexicanos to develop vocational skills that would help them succeed in the modern economy. He also backed water projects and initiatives to investigate land reform. The Conchas Dam project and the creation of new irrigation canals from the Rio Grande were among his pet projects.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

In the archive of Senator Chávez’s congressional and personal papers held at the Center for Southwest Research are numerous personal appeals from New Mexicans for relief during the depression. Similar to the countless letters written to President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his wife Eleanor, nuevomexicanos felt that Senator Chávez stood as their personal advocate in Congress. Indeed, Chávez’s advocacy for nuevomexicano issues during the New Deal often came at the expense of, or at least without consideration for, other groups of people in New Mexico.

When Congress passed the Taylor Grazing Act in 1934, Chávez worked to ensure that its provisions applied only to Navajos and Pueblos—not to nuevomexicanos. Senator Chávez also spearheaded a study of land grant titles in northern New Mexico. The result was that the terms of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ensured nuevomexicano rights to Spanish and Mexican Grants. As we will see in Chapter 15, such Congressional initiatives held little value.

W.T. Mullarky (photographer). Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 075000.

Chávez’s efforts shielded nuevomexicanos from the federal impetus toward livestock reduction. He recognized that animals equaled livelihood for most of the residents of the state. Yet his actions brought him into direct conflict with the head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, John Collier, who staunchly supported the conclusion that an overabundance of livestock wrought ecological damage across the Southwest. Despite Navajos’ reliance on mustangs, cattle, goats, and especially sheep, Collier pushed the livestock reduction program among them and other Native American peoples, as will be discussed in detail below.

During the New Deal era, other measures were taken to eliminate the partido system which, for all intents and purposes, was a form of debt peonage. As a result, New Mexico villagers received plots of land and loans to enable agricultural activity. The problem was that small-scale farming was no longer economically viable by the late 1930s, due to the rise of agribusiness. Without supplements, like seasonal, migratory wage labor, nuevomexicano villagers could no longer support themselves financially.

Despite some reformers’ realization that the Great Depression had impacted nuevomexicanos and Native Peoples, they still failed to dissociate their romanticized notion of pre-industrial lifeways from New Mexico’s diverse peoples. Their ways of thinking informed later efforts to address both cultural issues and the problem of poverty in the state. Although they did not realize it, they had framed the problems of New Mexico in a way that did not help nuevomexicanos or indigenous peoples as they attempted to face the economic, social, and political realities of the twentieth century.

Although political officials and reformers realized the impact of the Great Depression on New Mexico’s diverse peoples by the mid-1930s, they still failed to comprehend the extent to which New Mexico had been integrated into the national economy. Following decades of attempts to aid nuevomexicanos, by the end of the 1980s, five of the six poorest counties in New Mexico were between sixty-nine and eighty-seven percent hispano. The other was sixty-six percent Native American. Within those counties, thirty-two percent of the overall population lived beneath the federal poverty line.

As far as most of the people in such communities were concerned, food stamps and other forms of federal relief were “as little enough compensation for the loss of their old grant lands and no more than their due.”19 Historian Suzanne Forrest cites reports in the July and November 1937 Albuquerque Journal as the foundation for such attitudes, and other scholars and observers have continued to argue that an overemphasis on cultural preservation and a lack of work ethic explain the continuance of poverty in northern New Mexico.

Such explanations are problematic, however, because they fail to take into account the economic, political, and social structures that have taken root in New Mexico over the course of hundreds of years and three colonization projects. Colonialism has a strong legacy among nuevomexicanos and Native Americans in the area. As we will see in more detail in Chapter 14, racism and a lack of educational and economic opportunities cannot simply be written off as cultural issues. Economic and political contexts also play a role.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

The Hispanic New Deal made important contributions to the livelihood of northern New Mexicans and it provided a framework for preserving the area’s rural villages. Success stories like that of Chupadero and Taos illustrate that the WPA alleviated the suffering occasioned by the Great Depression. Yet vocational programs that focused on small-scale agricultural pursuits and the sale of craft items did not create a vital economy and many of the core issues that contributed to the area’s poverty were not addressed by New Deal programs.

After the New Deal and World War II, money for schools, literacy programs, job assistance, and cultural production was no longer available to the extent that it had been. By the late twentieth century, produce from family farms was barely enough to provide for basic subsistence. Few village industries developed as a result of earlier vocational initiatives, with the exception of the weavers of Chimayó. Locations, like Chimayó, Chupadero, or Taos, with proximity to tourist traffic, fared better in terms of marketing locally produced goods than other villages located off of the main highways. Senator Chávez recognized the need for more training in vocations, technologies, and skills that already seemed to be displacing things like craft production and agriculture during the 1930s and 1940s. Despite his ability to bring federal funds to New Mexico, such programs were generally the exception rather than the rule during the Depression era.