The History of New Mexico

Collapse

Expand

-

Chapter 13: The Great Depression & The New Deal

- The Great Depression & The New Deal

- Artist Colonies & Rural Reformers

- Depression Comes to New Mexico

- Dennis Chávez & The Hispanic New Deal

- Indian New Deal & Navajos

- References & Further Reading

Although the assertion that the Great Depression did not greatly impact New Mexico was overstated, the state was no stranger to poverty. The decade of the 1920s was characterized by the disenchantment embodied by writers, artists, and reformers. It was also defined by new economic prosperity and wealth for some Americans. That prosperity, however, was unevenly distributed across the nation. While some people drove new automobiles, others continued to walk or use draft animals. Some enjoyed the benefits of electricity and new household technologies, as others continued their day-to-day lives without.

Most nuevomexicanos did not benefit from the benefits of the 1920s economic upturn. New Mexico reported one of the highest rates of poverty in the nation, as well as high figures for infant mortality during the decade. Partido agriculture continued to dominate rural areas, especially in the north. On the eve of the stock-market crash in October 1929, the average rural family had only six acres of land under cultivation from which they typically made about $100 per year. At that rate, most families barely met subsistence standards.

Increased property taxes and debts required of partidarios combined to trap nuevomexicanos in a cycle of indebtedness. In exchange for new loans, they were forced to promise the next supply of wool from their sheep or the next agricultural harvest. In response, the men of many northern New Mexican communities became migratory laborers in an attempt to raise funds to pay their families’ debts. Across the Southwest, by traveling to pick sugar beets, work on railroad construction, or labor in mines and on cattle ranches, nuevomexicano families created what historian Sarah Deutsch has termed “regional communities.”12

Courtesy of Library of Congress

Nuevomexicanas generally maintained the family lands while their husbands and sons worked migratory jobs. Reformers targeted the women not only because they wanted to modernize processes that were typically viewed as women’s work, but also because women had taken on larger roles in their home communities due to the seasonal labor required of men to support their families’ village lifeways. Despite the continued perception that nuevomexicano villages remained pre-industrial, the need for migratory labor highlighted the ways in which local communities were actually incorporated into the national economy.

When the Great Depression began, nuevomexicanos’ seasonal jobs evaporated and their families were devastated. In some cases, the ranchers, farmers, or railroad companies simply cut back production. More typically, white men were given preference in the fields that Southwestern hispanos and Mexican migrants had formerly worked. During the 1930s, calls for the return of “alien” Mexican laborers to their home country limited job opportunities across the nation. Despite their U.S. citizenship, administrators in the U.S. Department of Labor, farm owners, and business proprietors drew no distinction between nuevomexicano men and Mexican migrants.

As a result, the northern New Mexican villages revered by artists and reformers faced extinction. During the first few years of the Great Depression, nuevomexicanos accounted for 80% of the state’s relief load. Also, those nuevomexicanos who attempted to maintain their seasonal jobs faced the specter of deportation to Mexico as programs to repatriate undocumented Mexican laborers intensified.

Depression conditions might have forced nuevomexicano villagers off of their lands, as was the case with the impoverished “Okies” and “Arkies.” Due to reformers’ ongoing fascination with the village, the state’s hispano populations instead received relief in the form of a unique Hispanic New Deal. Additionally, unlike californios and tejanos who had lost access to their respective states’ political systems in the nineteenth century, nuevomexicanos preserved a tradition of political participation and access that was further solidified following statehood.

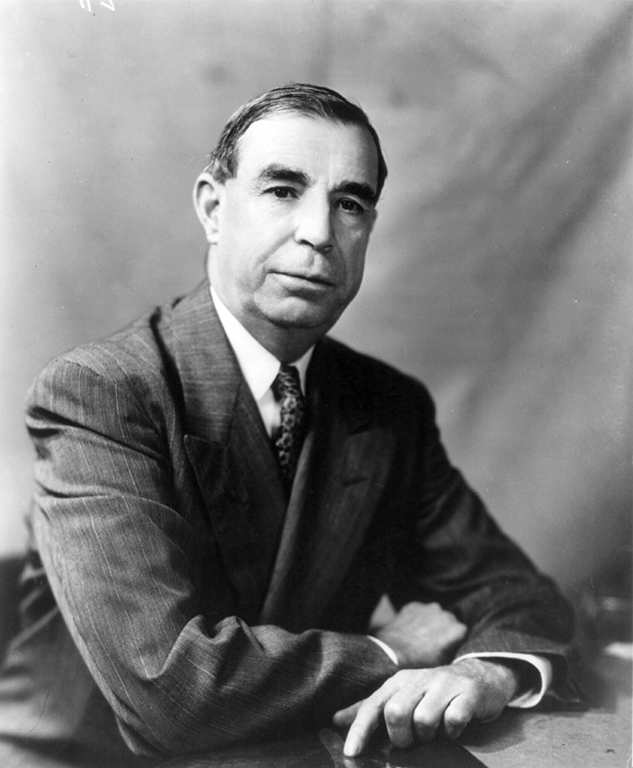

Courtesy of Library of Congress

Nuevomexicanos believed that they could turn to their elected officials to gain recourse for their problems. The Otero and Chávez families had maintained a place in the territorial government, and Governor Octaviano Larrazolo and Senator Dennis Chávez stand out as examples of hispano politicians in New Mexico in the three decades following statehood. Nuevomexicanos appealed to their elected officials in letters, meetings, and at the ballot box, whereas many hispanos in other parts of the Southwest did not.

Anglo-American officials, such as Governor Clyde Tingley, also often stood as advocates of the state’s hispano populations. In an effort to prevent people who he termed “alien migratory workers” from entering his state, Colorado Governor Edwin Johnson declared martial law along the state line with New Mexico. The Colorado National Guard prevented nuevomexicanos and Mexican migrants from traveling to work in the state. Within a few months, however, nuevomexicano laborers petitioned Governor Tingly to take action and he threatened to boycott goods from Colorado. The threat was enough to convince Governor Johnson to back down.