The History of New Mexico

Collapse

Expand

-

Chapter 6: New Mexico & The Battle for North America

- New Mexico & The Battle for North America

- Imperial Competition in North America

- Bourbon Reforms & New Mexico

- Late Colonial Age

- References & Further Reading

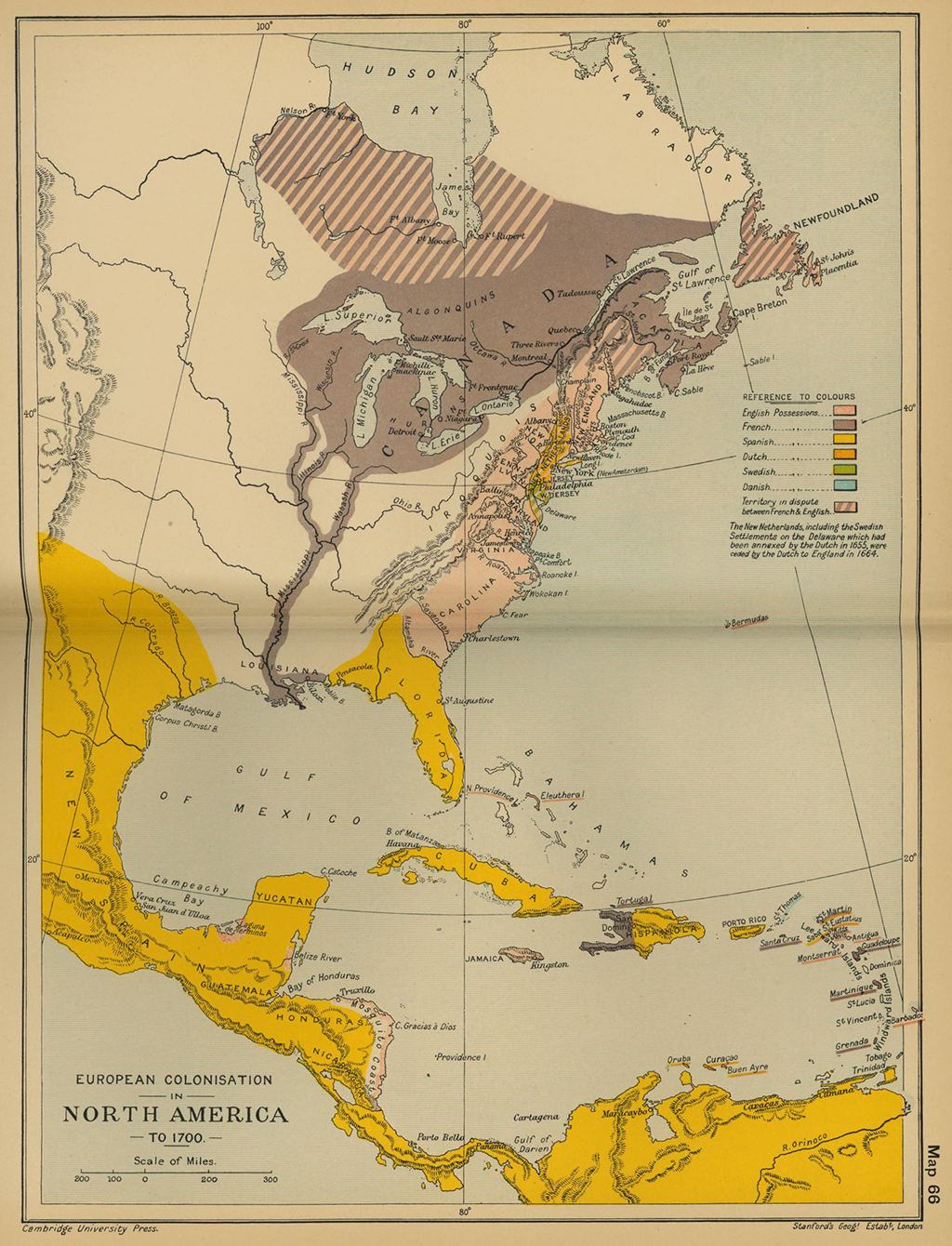

Courtesy of Library of Congress

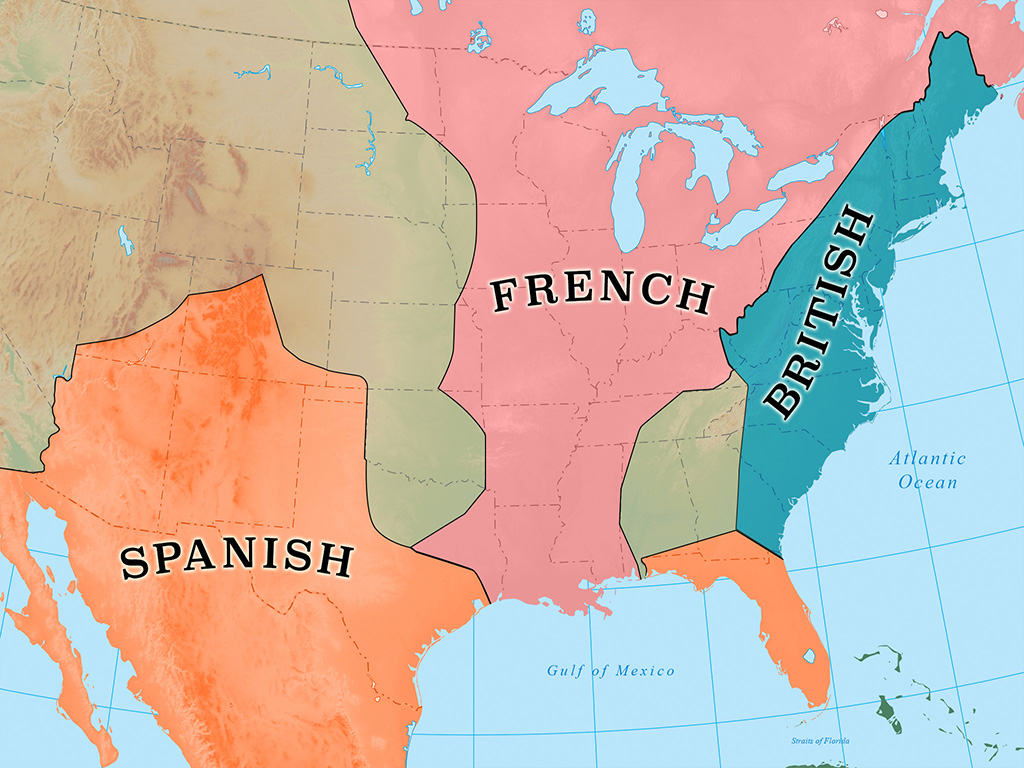

To understand late-eighteenth century relations between nuevomexicanos and Comanches, we must also consider the types of competition that defined relations between North America’s various inhabitants between the late 1600s and late 1700s. The French and the British sought to build North American empires to compete with Spain’s hold over most of the hemisphere. As each European empire worked to gain the advantage over the others, they also had to contend with a wide variety of indigenous peoples who sought to preserve their homelands and lifeways. As in the case of Pueblo savvy in negotiating the conflicts between various Spanish factions in seventeenth-century New Mexico, other peoples, such as the Illinois, Oendats (also called Hurons), and Iroquois, adeptly played Europeans off of one another to their own advantage whenever possible.

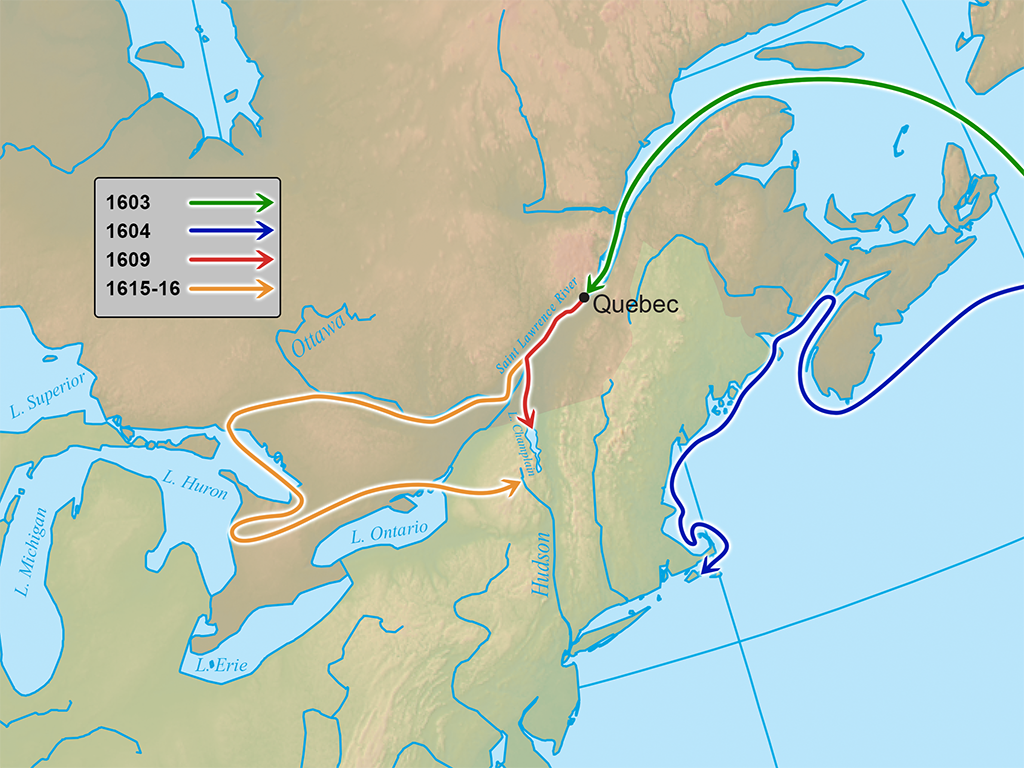

French settlement in North America began along the St. Lawrence River in the northeast. By the mid-sixteenth century, French explorers had established a series of fortified trading posts near the mouths of the St. Lawrence and Hudson Rivers. Much like the Portuguese, the French worked to create a commercial empire based on trade with native peoples. In the case of the area that became known as New France, French explorers sustained a lucrative trade with the Huron people and their allies for fish and beaver pelts.

Early settlements were lightly populated forts established for the sole purpose of preserving the French foothold in the region. By the early seventeenth century, however, French officials realized that they needed a stronger presence if they were to hold their claims against Dutch and British encroachment. To that end, in 1608 Samuel de Champlain led an expedition up the St. Lawrence River to establish the city of Quebec. Within a few years of one another, Quebec, Jamestown (1607), and Santa Fe (1610) were all founded as the French, British, and Spanish sought to shore up their own territorial claims against one another. Although those cities were distant from one another, geographic knowledge was limited. Each new colony was evidence of the respective empire’s desire to protect its place in North America.

Courtesy of University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin

Much like the Spanish, the French followed a model of inclusion relative to native peoples. They had realized early on that their place in the St. Lawrence River valley was tenuous; a handful of Frenchmen established initial ties with the Hurons, who numbered between 15,000 and 20,000. The French quickly realized that their very existence depended on friendly relations with indigenous peoples. Amicable contact with Hurons also shored up the fur trade that was the basis for Quebec’s economy. Early British attempts to colonize Roanoke were a known example of what could happen if Europeans attempted to subjugate native peoples when they were in a precarious position themselves.

After 1663 Quebec became a royal colony, under the purview of King Louis XIV who issued an official policy to promote intermarriage between French colonists and indigenous peoples in order to strengthen France’s place in North America. Specifically, the policy was an attempt to address the issue of meager population growth in the colony. Despite efforts to attract European migrants through a system of indentured servitude and enticements to bring orphaned children or widowed women, known as filles du roi (king’s daughters), the population of French-heritage colonists remained small—especially when compared to the large numbers of indigenous peoples in the St. Lawrence River area. The French learned to create peace with natives through a Jesuit-led conversion effort that was far more willing to accept blended belief systems than the Spanish mission system. They also established strong trade relations with Huron and other peoples as they continued to migrate throughout the Great Lakes region, down the Mississippi River. The French remembered that “Native Americans thought of trade not simply as an economic activity but rather as one aspect of a broader alliance between peoples,” a lesson that was often lost on Spanish settlers.4

Courtesy of Library and Archives Canada, Acc. no 1996-371-1

With LaSalle’s 1682 navigation of the Mississippi River, French explorations began to impact the course of New Mexico’s histories. As he sailed south, La Salle made the initial French claim on the area that became known as Louisiana, in honor of King Louis XIV. By 1683 La Salle had returned to France to propose the creation of a new French colony near the mouth of the Mississippi that would serve as a springboard to further exploration and settlement in the region. With royal support, on August 1, 1684, he embarked on his colonization mission. In part, his proposition depended on France and Spain’s continued hostilities, which seemed likely because they had been fierce competitors for centuries. Two weeks after he set sail, however, the two kingdoms negotiated a peace settlement.

Courtesy of National Gallery of Art, Washington

Courtesy of Library of Congress

No longer interested in waging war against New Spain, Louis XIV withdrew royal assistance for La Salle’s venture. The small expedition of about 280 people was left to its own devices. Although La Salle left France with four ships, by the time he reached the Gulf of Mexico only one remained. One ship had been taken by pirates and another ran aground in the West Indies. A third ship remained in the Caribbean rather than continue the seemingly disastrous mission. As La Salle attempted to locate the mouth of the Mississippi, he miscalculated and became lost. Eventually, his crew disembarked on the present-day Texas mainland where they constructed a base of operations from which La Salle intended to locate the river overland. The forty or so who remained with the expedition fanned out in all directions for the purposes of exploration and opening relations with local native peoples. In the process of their various journeys, La Salle’s companions became fed up with his leadership and initiated a mutiny that resulted in his murder in March 1687. Exposure, disease, and conflicts with hostile native peoples had taken a great toll on the French survivors by that point.

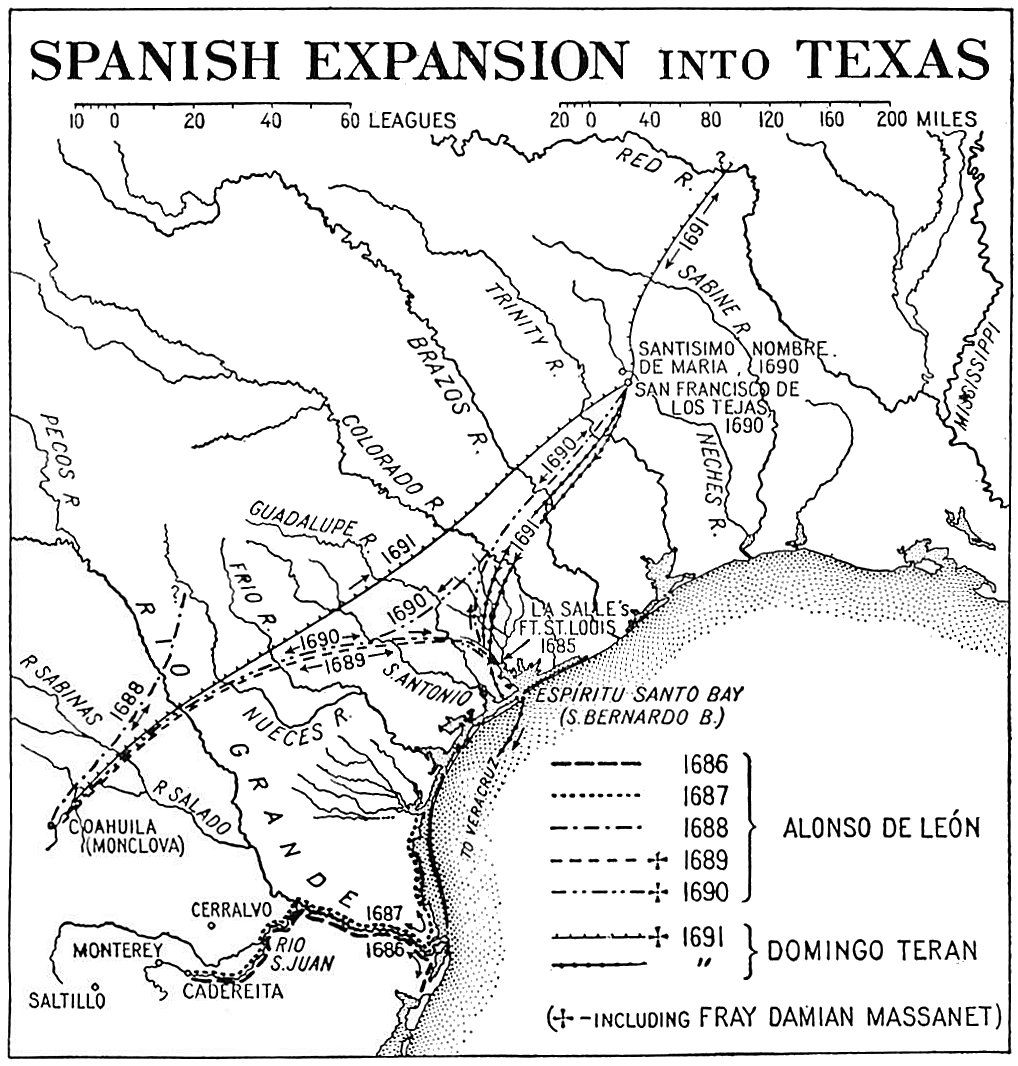

Although French officials maintained secrecy about the true aims of La Salle’s mission, Spanish officials learned in 1686 of his intent to establish a French stronghold that would isolate Florida from northern New Spain. Worried about the implications of such a development, they hastily organized an expedition to locate La Salle. Over the next three years, a total of six Spanish expeditions combed the area of present-day Texas in search of the French colonists. Some of the earlier expeditions located abandoned forts that La Salle’s group had constructed, but not until 1689 did the Spaniards learn about La Salle’s fate.

A party led by Alonso de León, governor of Coahuila, located two French survivors, Jean L’Archevêque and Jacques Grolet (progenitors to New Mexico’s Archibeque and Gurulé families), who were then living among native peoples in east Texas. From them, they learned of the disastrous results of the French attempt to colonize Louisiana. Although León did not know at the time, L’Archevêque had played a direct role in La Salle’s murder. In an effort to evade capture and prosecution by French officials, L’Archevêque joined León’s group. He later accompanied Vargas during the reconquest of New Mexico.

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Following León’s report of his findings, officials in Mexico City and Madrid quickly decided to expand the Spanish presence in the area between New Mexico and Florida. Other French explorers followed La Salle and solidified France’s claims on the Mississippi River corridor. To hold off further French advances, the first town in what became known as Texas was settled in the early 1690s. Over the next three decades, several small mission-presidio complexes sprung up in Texas. Although Spanish officials pointed to these settlements as evidence that the Spanish Empire controlled the area, the reality on the ground was far more precarious for Texas’ first European settlers. Due to their small numbers, Spanish Texans remained at the mercy of native peoples, such as the Caddos, Lipan Apaches, and Comanches. The settlers were obligated to exchange gifts with the natives on their terms, a grudging recognition of indigenous political and economic power.

By Texas’ early days, Comanche bands had already begun to build dominance on the southern plains. Their use of the horse and European weaponry, acquired through trade with French merchants, contributed to their ability to construct an empire. Although Spanish, and later Mexican, officials refused to acknowledge it, Comanches dominated the borderlands through the mid-nineteenth century. Only recently, historians have recovered Comanche perspectives on this period of the region’s history, enabling them to tell the story of their strength and prowess. Unlike European models of expansion and political control, the Comanche model of empire was not based on claiming land or imposing borders. Instead it was based on the trade of goods and captives, building new kinship ties, dominance in warfare, and raiding.

With such factors at play, colonial Texas remained in an insecure position. The town of San Antonio de Béxar was established in 1718 and it quickly became the political and economic center of Spanish Texas. Commonly referred to as Béxar during the colonial era, San Antonio was a way station between missions in East Texas and the Rio Grande corridor. In an effort to strengthen the settlement, Spanish officials promoted migration from Spain, Cuba, the Canary Islands, and northern New Spain. Most people had no desire to relocate, however, no matter the incentives. There was no guarantee of safety against indigenous peoples in Texas. As late as 1742, Spanish Texas only held about 1,800 colonial settlers. At the 1790 census, Texan settlers numbered only about 2,500.

Along with providing the impetus to colonize Texas, the French presence in Louisiana also impacted nuevomexicanos in the form of new trade opportunities. Much of the trade with New Mexico arrived through indigenous middlemen. At the turn of the eighteenth century, for example, Apache traders first arrived at Pecos and Taos with French finished goods. The addition of European wares to the annual trade fairs was a welcome development in the colony because manufactured goods were expensive and rare. Spanish imperial economic policies placed tight restrictions on the way that trade was organized. Certain merchants were designated as official traders, and no others were legally allowed to exchange goods in Spanish domains. In the northern frontier of New Spain, merchants based in Ciudad Chihuahua claimed the official monopoly on trade along the upper Camino Real. This type of system was intended to keep all of the empire’s wealth within the empire itself. Scholars have termed this type of tightly regulated economic system mercantilism. Although all European empires were mercantilist in the eighteenth century, Spain’s system was the most byzantine.

Photograph by Robert Norment

Trade in French goods through native intermediaries was both exciting and troublesome for New Mexico’s administrators. On the one hand, the goods were sorely needed in the colony. On the other, trade outside of the official channels was a violation of Spanish law. Due to isolation and longstanding efforts to maintain peaceful relations with regional nomadic peoples, officials tended to look the other way when indigenous traders entered New Mexico’s markets. Trade provided an important channel of communication and negotiation that quickly transformed into raiding and warfare anytime it was closed off. Indeed, native raids took a toll on New Mexico’s population throughout the eighteenth century. Apache bands threatened settlements along the Rio Grande corridor. Western land-grant communities in the area between Albuquerque and Mount Taylor (Sierra de Cebolleta) tried to fend of Navajo raids. Far northern settlements feared the Ute people, and in the northeast Comanches worked to enhance their dominance through raiding. In that context, officials capitalized on any opportunity to build friendlier relations based on trade.

The presence of French merchants and explorers themselves, however, presented a different conundrum for nuevomexicano officials. In 1706 Juan de Ulibarrí, one of Albuquerque’s founders, heard rumors that the French had forged ties with Pawnee people on the central plains near the Platte River. French traders trekked from Natchitoches in western Louisiana to Santa Fe between 1719 and 1721. Just as the trading party set out, Governor Antonio Valverde learned from Apache allies that the French had established two towns among the Pawnee, each “as large as that of Taos.” The Apaches also reported that the Pawnees used French firearms in a recent skirmish between their two peoples. To round out the report, they added that the French among the Pawnees had insulted Spanish honor by derisively calling them women. That same year, French forces attacked outposts in east Texas, led an offensive on Pensacola in Spanish Florida, and declared war against Spain in Europe.

Within the context of perceived French aggression, Valverde outfitted an expedition of forty-five nuevomexicanos and sixty indigenous allies under the command of lieutenant governor Pedro de Villasur. In July 1720 Villasur’s group set out on a path toward the north with orders to spy on the French and to verify the news conveyed by the Apaches. Jean L’Archevêque went along as interpreter. Much to Villasur’s surprise, the march between Santa Fe and El Cuartelejo (a site in present-day southern Colorado) passed without incident. Earlier nuevomexicano forays into the area had been confronted by Comanche war and raiding parties there. As the group made its way toward the confluence of the North and South Platte rivers in present-day central Nebraska, Villasur saw no sign of the alleged French settlements.

On August 13, just as Villasur’s men made final preparations to return to New Mexico, a combined Pawnee and Otoe force attacked. Despite their best attempts to defend themselves, the nuevomexicanos were taken off guard. Only thirteen members of the expedition survived to tell the tale in Santa Fe. Villasur and L’Archevêque were counted among the casualties. When the horrified survivors told their tale, fear of impending attack spread across the colony. Nuevomexicanos believed that the French must have put the Pawnee and Otoe peoples up to the massacre. Governor Valverde organized improved defenses around New Mexico’s perimeter. The story of the Villasur massacre, as well as several other nuevomexicano campaigns against native peoples between the 1690s and 1720 were recorded via paintings made on hides. Known as the Segesser Hide Paintings, their origins are obscure. Historians, such as Thomas Chávez, believe, however, that a father-son pair with the surname Tejeda created them. The younger Tejeda served under Villasur and was killed in the battle. If the hypothesis is true, the senior Tejeda painted a remembrance of the mission in which his son, and painting partner, had been killed.

By 1721, France and Spain had once again negotiated peace. During the short period of their aggressions, however, Spanish Texas was strengthened by the addition of new presidios and military units. New Mexico seemed to be in a vulnerable position, and Governor Valverde prepared the colony for the worst. As French weapons and goods filtered into the Taos trade fair, nuevomexicanos ignored trade prohibitions and armed themselves in any way that they could.

When the French threat subsided, the practice of acquiring French goods through Apache and Comanche traders only grew. In 1739 Pierre and Paul Mallet, French traders from Illinois, made their way to New Mexico with six companions. New Mexico officials reported that the Mallet party entered Santa Fe without any merchandise, having lost it during a rough river crossing. As they waited for word from the viceroy on what to do with the Frenchmen, the outsiders received great hospitality for a period of about nine months. Ultimately, the official word was that the Mallets had to leave or face arrest—the trade prohibition would be enforced.

The official report of the lost merchandise may have been a fabrication to hide the fact that nuevomexicanos had traded with the Mallets. Suffering due to scarcity of manufactured goods, and weary of the Chihuahua merchants’ exorbitant prices, at least one frustrated nuevomexicano sent a shopping list with the Frenchmen when they left New Mexico. When the trading party returned to Illinois, French merchants there drew two conflicting conclusions based on the experience. First, Spanish officials had prohibited their entry into northern New Spain. Second, and somewhat contradictorily, nuevomexicanos wanted access to new wares and trade options. As a result, French traders occasionally tried their luck in New Mexico during the rest of the eighteenth century.