The History of New Mexico

Collapse

Expand

-

Chapter 16: Into the 21st Century

- Into the 21st Century

- Lowrider Culture

- Rock Your Mocs

- Indigenous Resistance Tour of UNM

- Jemez Pueblo & Valles Caldera

- Ending Remarks

In 1997, eighty-five years after achieving statehood, the state legislature decided to commission a statue of Po’pay as the second piece from New Mexico to be included in the National Statuary Hall Collection in Washington, D.C. The first statue was a likeness of Senator Dennis Chávez that was donated to the collection in 1966.

In 1999, Jemez Pueblo sculptor Cliff Fragua received the commission to create the likeness of the leader of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. After six years of work, the seven-foot statue created from pink Tennessee marble was unveiled. Fragua’s own description of his portrayal of Po’pay is poignant enough to quote at length:

In my rendition, he holds in his hands items that will determine the future existence of the Pueblo people. The knotted cord in his left hand was used to determine when the Revolt would begin. As to how many knots were used is debatable, but I feel that it must have taken many days to plan and notify most of the Pueblos. The bear fetish in his right hand symbolizes the center of the Pueblo world, the Pueblo religion. The pot behind him symbolizes the Pueblo culture, and the deerskin he wears is a humble symbol of his status as a provider. The necklace that he wears is a constant reminder of where life began, and his clothing consists of a loincloth and moccasins in Pueblo fashion. His hair is cut in Pueblo tradition and bound in a chongo. On his back are the scars that remain from the whipping he received for his participation and faith in the Pueblo ceremonies and religion.1

Cliff Fragua

Courtesy of Indian Pueblo Cultural Center

The presence of Po’pay’s likeness in the nation’s capital is a powerful testament to the resilience and fortitude of Pueblo peoples. Their vibrant traditions and stories have not only survived centuries of colonialism, but they continue to flourish. Indeed, if they were able to visit the present, figures like Juan de Oñate and General James H. Carleton would be surprised at the vibrancy of Pueblo, Navajo, and Apache cultures today. During their respective lifetimes, they believed that indigenous peoples were destined to fully assimilate into the colonial religious and social practices.

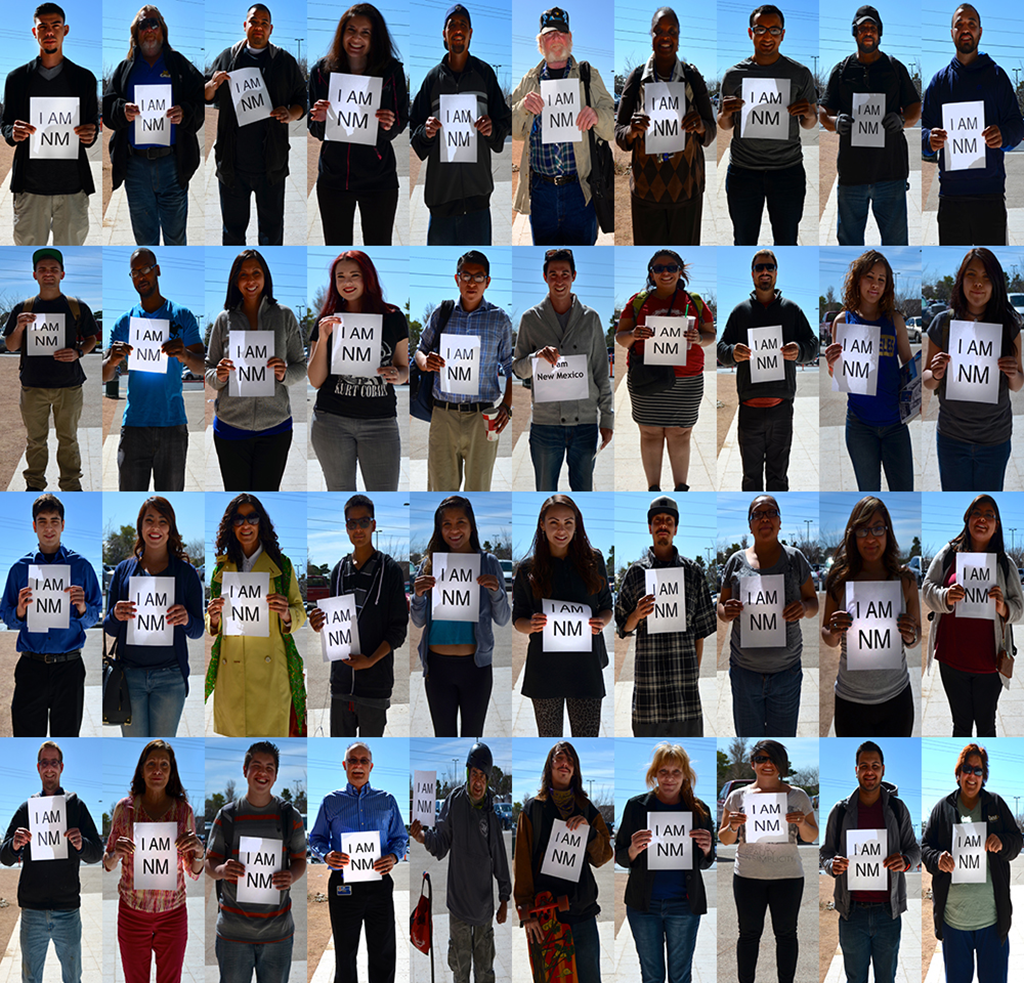

New Mexico’s varied histories emphasize the value of understanding other groups of people on their own terms. This region’s past is complex and heavily contested. It remains a place that is conflicted between its roots in indigenous, Spanish, Mexican, and U.S. stories. People of all ethnic backgrounds, not only Native American, Hispano, and Anglo-American have made New Mexico their home, and all have a unique perspective on the meaning of the place and its past.

In this brief final chapter, I hope to emphasize once again that there is no such thing as “New Mexico History” in the singular. Instead, New Mexico’s past is comprised of multiple stories and traditions. Conflict, accommodation, and resilience are among the central themes of these histories. Although the idea of tri-cultural harmony originally posited by Governor L. Bradford Prince in the late nineteenth century is problematic, New Mexico has long been a place where peoples of diverse worldviews have worked out their differences. At times intense violence has marked regional conflicts; at others compromise and accommodation carried the day.

As the people of New Mexico enter the twenty-first century and look toward the future, many problems persist. Poverty among rural nuevomexicano and Native American peoples has yet to be resolved. Atomic developments have devastated local environments. Yet New Mexico is also known as the Land of Enchantment, a place of beauty where differences are appreciated. The notion that New Mexicans—whatever their cultural or ethnic background—can work out divisive, harsh differences provides hope for the future. As we learn from our past, we are better able to understand one another and create a more harmonious society.

The descriptions, links, and videos that follow provide a lens into New Mexico in the early twenty-first century. Native American and nuevomexicano people continue to shape local society, even as they struggle to assert their rights to full U.S. citizenship. In terms of protecting and providing civil rights for all, much progress has been made. By learning the lessons of New Mexico’s diverse histories, the future can be a place where new strides toward equality become a reality.

Courtesy of Students, Faculty and Staff of Central New Mexico Community College