Two separate ceremonies held two weeks apart in Santa Fe marked Mexico’s independence from Spain. The first was held on December 31, 1821, by order of Agustín de Iturbide, Mexico’s first (and only) emperor. Organized by Facundo Melgares, the event focused on the tres garantías (or three guarantees) ensured by the brand-new Mexican empire: Catholic Religion, Union, and Independence. In Santa Fe, on a stage erected near the Palace of the Governors, Don Juan Bautista Vigil y Alarid led ceremonies that focused on symbols of each of the three items guaranteed by the Mexican government. Three images, a lamb and lion engaged in an embrace, a liberty tree fed by four rivers, and a representation of Agustín de Iturbide, graced the stage as speakers extolled the virtues of the Catholic faith, union, and independence.

Striking quite a different tenor, the second ceremony took place on January 6, 1822—the feast day of Los Reyes (the three Wise Men, or the Magi). During this procession, nuevomexicanos turned out in the bitter cold through all hours of the night to honor those that had sought out the Christ child, according to Catholic legend. The occasion was marked with parades, patriotic plays, masses, music, rifle fire, Pueblo dances, and a ball sponsored by the governor. The January festivities clearly illustrated the tight connections between the Catholic faith and the idea of Mexican nationality. Future commemorations of Mexican independence held on the 16th of September followed a similar pattern.

What did these processions mean to nuevomexicanos? Although we cannot know with certainty, most of New Mexico’s mixed-heritage residents likely reacted with much the same feeling as Pueblo people who heard Oñate’s first strains of the requerimiento. Most hoped to continue with their daily routines in the remote desert landscape that they called home without interference from the government in Mexico City. In certain respects, they got their wish. Political infighting and economic devastation linked to the independence effort meant that Mexican officials largely ignored conditions in the north. Officials’ indifference and their outright inability to provide support, however, also translated into the erosion of peace and a renewal of cycles of retributive violence between nuevomexicanos and their nomadic neighbors.

Post-Mexico Independence

WITH BRANDON MORGAN, PH.D.

The Mexican nation’s shaky foundations are explained in part by the conditions under which it gained independence from Spain. Following Napoleon’s 1808 installation of his brother Joseph on the Spanish throne, resistance movements sprang up across the Spanish Empire. In Iberia, a representative body called the cortés formed at Cádiz to rule in the name of Fernando VII. Similar cortés took shape in the empire’s major urban centers, such as Buenos Aires. Although their stated purpose was to maintain Spanish governance until the return of the rightful king, the cortés hoped to create conditions in their respective regions for liberal governance. Early nineteenth-century liberalism was based on Enlightenment ideals such as constitutional government and the protection of individual liberties, including freedom of speech, to assemble, and of religion. In New Spain, however, the conservative viceroy and his closest advisors opposed such notions. They vocally opposed the liberal Constitution of 1812 issued by the cortés in Cadíz and hoped to maintain traditional social and political structures.

Mexico City’s leadership considered liberalism to be an invitation to uprising and social reordering. Even before the Cadíz Constitution was issued, their fears seemed to take shape when criollo priest Miguel de Hidalgo y Costilla incited his parishioners to action with the Grito de Dolores. Hidalgo’s was a popular movement—most of his parishioners were poor natives or mestizos—that called for independence from the “gachupines” (a derogatory term for Spaniards). The independent status that they imagined was based solely on their call for an end to “bad government” under the watchful eye of the Virgen de Guadalupe.

Within a few months, Hidalgo had nearly 50,000 at his command. As numbers grew, however, the father of Mexico’s independence was unable to maintain discipline among his troops. In Guanajuato, for example, his forces killed 500 Spanish soldiers and civilians. Although it appeared that they would next turn against the capital, Hidalgo’s forces instead marched northward for unknown reasons.

After Hidalgo’s capture and execution in Chihuahua in mid-1811, another priest, Padre José María Morelos, took up the charge. Unlike Hidalgo, Morelos was of mestizo background—likely with both indigenous and African heritage. His platform was more clearly defined and much more troubling to Mexico City leadership. Morelos called for social and racial leveling. As he declared, “The lovely nonsense that divided Indians, mulattoes, and mestizos into distinct ‘qualities’ of human beings is henceforth abolished. From now on, all are to be called americanos.”1 He held a broad democratic vision that would include all as citizens of the Mexican Republic. As some of his reforms took hold at the local and regional level in the area south of Mexico City, New Spain’s criollo elite threatened genocide in an attempt to quash the movement. Royal forces captured and executed Morelos in 1815.

Although strains of Hidalgo and Morelos’ popular movements for independence continued under other leaders, specifically Vicente Guerrero, Mexico’s final break from Spain came under much more conservative auspices. Much to the relief of viceregal authorities in Mexico City, Fernando VII revoked the Cadíz Constitution when he returned to the throne in 1814 on the heels of Napoleon’s defeat. In 1820, liberal members of the Spanish military staged a revolution that forced the king to reverse his decision and accept the constitution that had been drafted by the cortés in his absence. Fernando’s decision to allow for constitutional rule alarmed conservatives in Mexico City, who ultimately decided that independence from Spain would be the only way to maintain the traditional social, economic, and political order—an order in which they held immense power. On August 24, 1821, Spain’s envoy in Mexico City signed the treaty that recognized the independence of the Mexican nation.

General Agustín de Iturbide led the successful charge for independence by enlisting the aid of his political and social opposition, including Vicente Guerrero. He declared himself the first emperor of Mexico in September 1821. As the events of Mexico’s independence movement illustrate, autonomy from Spain meant very different things to different groups of people. Many throughout Mexico championed the liberal ideals of Hidalgo and Morelos, others supported the conservative old guard, and still others (including most nuevomexicanos) wanted simply to be left alone. In the 1940s, historian Lesley Byrd Simpson coined the idea that historically there have been “many Mexicos.” In the early years following independence that concept was borne out by the difficulty of constructing a common national identity among peoples who held different customs and beliefs, spoke different languages, and faced different day-to-day concerns, but who lived in the territory defined as the Mexican nation.

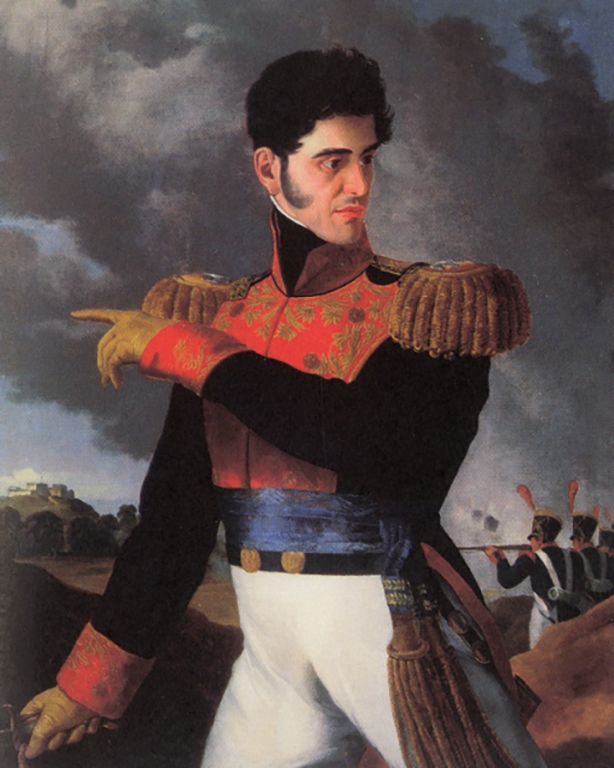

By 1824, Iturbide’s empire met its end when a coalition led by Vicente Guerrero and the wily Antonio López de Santa Anna enacted a successful coup. Iturbide’s decision to dissolve Congress galvanized the opposition. Like the composition of Mexico itself, the opposition included men of various ideological, economic, and ethnic backgrounds. Although the most prominent ideological and political divide was between federalists (generally liberals) and centralists (generally conservatives), such factionalism was never drawn along clear-cut lines. Instead, opportunism, economic concerns, pragmatism, and a number of other factors often caused Mexican leaders to alter their ideological or political stances. Put differently, for example, federalists tended to be regional elites while centralists were national elites. Both groups contained wealthy figures who traced their lineage—at least in part—to Europe.

Following the coup against Iturbide, federalists held power in Mexico City. The Mexican Constitution of 1824 was drafted under their purview, and it reflected the critical difference between their faction and the centralists—the desire for a federal system of government. Federalists hoped to maintain regional autonomy by creating a government in which power was shared between state and local governments and the national government in Mexico City. The key to their vision of the republic was shared governance (much like the U.S. system). Centralists, on the other hand, wished to curb regional political authority by placing more power in the hands of the national government.

The 1824 Constitution of the United States of Mexico (or Estados Unidos Mexicanos) designated nineteen “independent, free, and sovereign” states and four territories that remained more tightly under the auspices of Mexico City.2 The document was based heavily on the 1812 Cadíz Constitution and that of the young U.S. republic. The Mexican constitution guaranteed individual liberties, freedom of speech, assembly, and press and the division of power between executive, legislative, and judicial branches. Of necessity, it embraced the stipulation from the Cadíz Constitution that political authority rested principally in regional ayuntamientos. Unlike the U.S. Constitution, it established the Catholic faith as the official state religion and maintained special privileges for clergy and military officers, called fueros. In terms of political inclusion, it went far beyond its U.S. counterpart, ending (in theory, at least) all distinctions based on race or caste and extending the vote to all Mexican males. Any person born within Mexico’s national borders was granted citizenship—including nomadic peoples who did not recognize Mexican sovereignty.

Under the 1824 Constitution, New Mexico was given territorial status, meaning that it operated under the jurisdiction of the national government rather than as an autonomous political entity. Technically, nuevomexicanos depended on Mexico City officials for legislation and governance, but the national government never implemented any territorial laws. Civil officers replaced royal appointees in certain administrative posts. Local ayuntamientos performed most of the work of governance and they operated with very little oversight from the national government, leaving the New Mexico territory self-governing by default.

In certain ways, these were welcome developments. Yet in other respects, especially in terms of dealing with Comanches, Apaches, Navajos, and Utes, nuevomexicano officials required economic and military support from the central government that was never forthcoming. New Mexico remained an impoverished frontier region that consistently failed to raise enough revenue to run its government effectively. Spanish subsidies that had provided gifts to solidify peace with nomadic peoples ended with independence, and Mexican officials were both unwilling and unable to renew them. Beginning in the early 1830s, one of the most devastating periods of Comanche and Apache warfare took hold throughout northern Mexico.

Figures like Padre Martínez played the crucial role of helping nuevomexicanos identify with the Mexican nation. His personal influence as someone who cared for the best interests of most people, despite his elevated economic status, enabled him to act as an ambassador of sorts. Yet even Martínez realized that not everything associated with independence was positive for New Mexico. Despite its promise to enhance New Mexico’s economic situation, the Santa Fe Trade brought newcomers from the United States whose ideas about race and ethnicity caused them to look down on nuevomexicanos. Many who traveled the Santa Fe Trail established homes and families in New Mexico and other areas in the Mexican north.

What was the Santa Fe Trail?

Near the end of the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, Santa Fe was part of a commercial highway called the Santa Fe Trail. Santa Fe connected New Mexico’s economy with the United States to the east: Colorado, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Missouri. After the U.S.-Mexican War, the economic route played a vital role in the United States expansion into the west. The documentary below was created to celebrate the 175th anniversary of the Santa Fe Trail from the point of view of the Hispanic and Native American people of the territory of New Mexico.

Santa Fe Trail Beginning in 1821, the Santa Fe Trail opened trade connections not only between Missouri and New Mexico, but it also created trade avenues that extended along existing lines, such as the Camino Real and canals and overland routes to the eastern seaboard. The Santa Fe Trail played an instrumental role in reorienting New Mexico’s economy toward the United States.

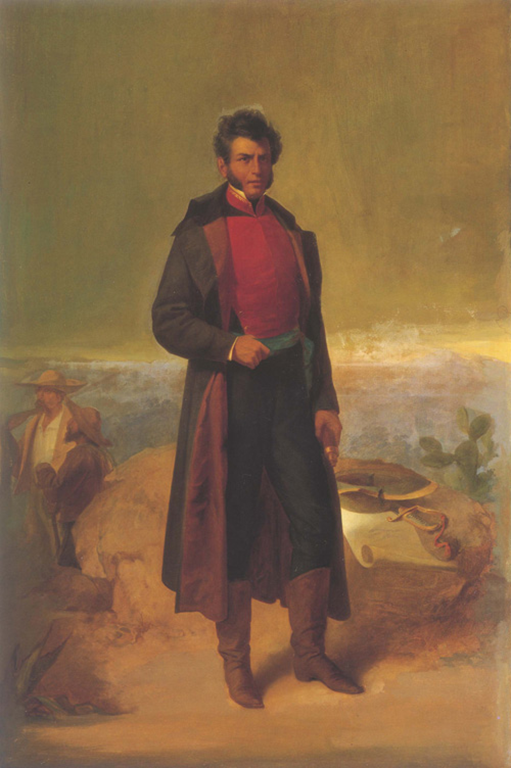

This is the only known image of Manuel Armijo, governor of New Mexico, on several different occasions during the Mexican period. Armijo is a much-maligned figure in New Mexico history due to his favoritism of Americans in land-grant proceedings, as well as his surrender of Santa Fe without a fight in 1846.

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Particularly onerous to Padre Martínez and some other nuevomexicano politicians was Governor Manuel Armijo and his practice of granting land to Santa Fe traders. Under the Mexican administration, regional officials played a larger role in granting land and resources. Governors held the authority to approve or veto grants made by town councils. During his various periods of service as New Mexico’s governor (1827-1829, 1837-1844, and 1845-1846), Armijo approved the majority of grants created by the territory’s ayuntamientos—in all, nearly sixteen million acres. Many such grants were made to American traders who were also close associates of Armijo and his rico nuevomexicano associates. The governor claimed that his actions were to solidify Mexico’s hold on northern hinterlands, an argument that dovetailed nicely with prevalent ideas in Mexico City about increasing the population in order to prevent national territory from falling into the hands of nomadic peoples or the United States. Padre Martínez, on the other hand, accused Armijo of “the mean and ambitious desire of delivering a portion of this Department into the hands of some foreigners.”3