The History of New Mexico

Collapse

Expand

-

Chapter 9: Territorial New Mexico

- Territorial New Mexico

- Civil War in New Mexico

- The Navajo Long Walk

- New Mexico as "Wild West"

- References & Further Reading

Along with creating the conditions in which Navajos and Mescaleros were able to return to a portion of their respective homelands, the close of the Civil War created an influx of immigration to New Mexico from the east. Men who had served on both sides of the conflict either came alone or brought their families to the territory in search of the opportunity to start over and, hopefully, make a fortune by exploiting New Mexico’s lands, resources, and people.

New Mexico’s territorial status facilitated such ambitions. By keeping the area under the direct jurisdiction of Washington, D.C., longstanding New Mexico residents were allowed only second-tier U.S. citizenship. As voiced with much vitriol and racism by South Carolina Senator John C. Calhoun regarding the addition of the Mexican cession to the United States, “Ours, sirs, is the Government of a white race. The greatest misfortunes of Spanish America are to be traced to the fatal error of placing these colored races on an equality with the white race.”24 Despite vocal criticism of Calhoun’s position, notably from Representative Joseph M. Root of Ohio, a majority of U.S. Congressmen actively worked to ensure that the inclusion of nearly 100,000 former residents of Mexico would not end white Americans’ domination over those they referred to as the “colored races.”

Within such a context, Anglo newcomers to New Mexico, whether government appointees to territorial office or immigrants, manipulated territorial politics with ease. A string of presidential appointees to the governor’s office proved to be more concerned with their personal enrichment than with the needs of the territory. Under the territorial system, democracy was virtually non-existent. Nearly a century earlier, the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 had established the protocol for the governance of new lands, as well as the process by which they could enter the Union as full-fledged states. The Compromise of 1850 added certain stipulations for New Mexico’s territorial system, including the presidential appointment of New Mexico’s entire judicial branch.

No matter the dealings in Washington, D.C., New Mexicans, Pueblos, and the territory’s indigenous peoples were coerced U.S. citizens—they did not choose to belong to the United States. However amiable their relations to U.S. officials might have been, from the arrival of Kearny’s Army of the West, they were forced at bayonet point to join the nation. Congress looked down on them, and believed that it was the steward of the people of the New Mexico Territory.

The territorial government was always a government of outsiders. The governor, territorial secretary, federal justices, attorney general, U.S. marshal, and commissioner of the land office were presidential appointees. Such officials came and went, depending on the whims of the electoral cycle and the administration itself. According to U.S. precedent, the only elected body was the territorial legislature. Territorial status greatly limited the potential for democracy and allowed unscrupulous people to take advantage. Tellingly, the position of territorial delegate to Congress—effectively a representative that lacked the ability to vote on any measure taken up by the national legislature—garnered the most political prestige during the territorial period.

Territorial constraints, coupled with the rise of a Gilded Age in the United States at the national level, paved the way for the rise of a political machine known as the Santa Fe Ring. Despite its ubiquitous appearance in territorial newspapers, existence of the Ring is a matter of dispute among modern historians. Of the very few books on the topic, only one, Chasing the Santa Fe Ring, by David L. Caffey, has been published recently (2014). As Caffey points out, part of the reason that doubts about its existence persist is the fact that adversaries of alleged Ring members conjured the term in an attempt to attack the actions of their political opponents. Indeed, territorial newspapers cast the Ring as either “a systematized organization of rascality” or as a body that advanced “individual interests at the expense of the general welfare.”25 Neither depiction was particularly flattering.

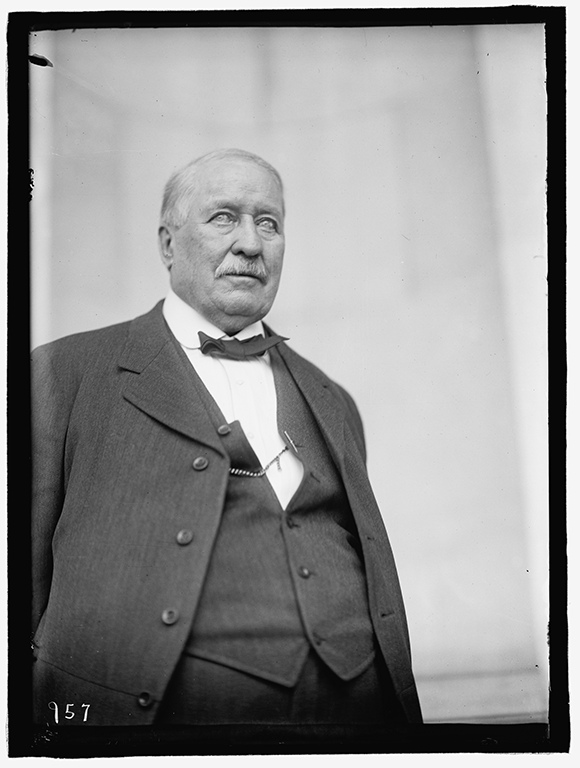

Courtesy of Library of Congress

As Caffey has also shown, academic historians have all too frequently taken at face value the partisan accusations levied in the territorial press. Although monographs on the Santa Fe Ring are few and far between, many historians of the territorial period mention the political machine as a powerful and negative force in nineteenth-century New Mexico. Of course, the Ring itself never published its minutes, never announced its incorporation. Neither did its alleged affiliates ever publicly acknowledge its existence. Its members were far too smart for that. Instead, we are left to infer the Ring’s actions from what we know of the American Gilded Age and of New Mexican politics in the late-nineteenth century. Similar political machines surfaced in the Utah, Colorado, and Arizona Territories, but none has garnered the romanticized legacy of the Santa Fe Ring.

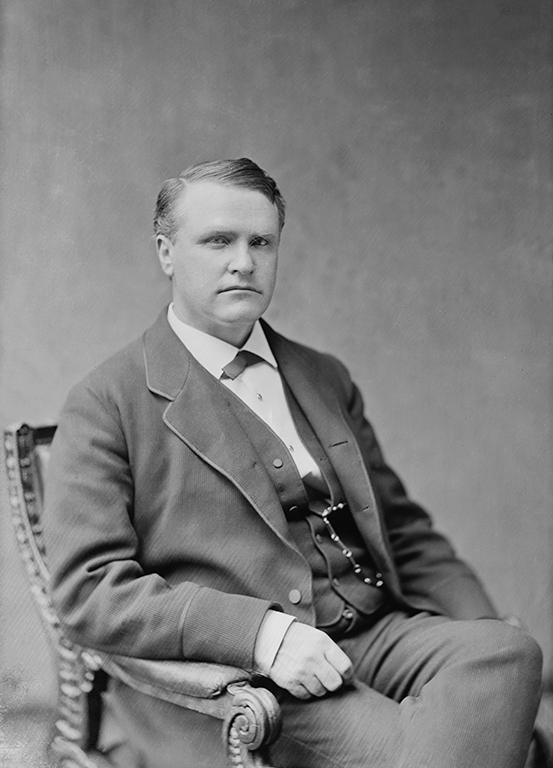

Courtesy of Library of Congress

All of that is owed, at least in part, to Thomas B. Catron—recognized ringleader of the New Mexico political machinery. After fighting for the Confederacy, he relocated to Santa Fe based on favorable reports from his former college roommate, Stephen B. Elkins. Not long after his arrival in Santa Fe, Catron opened a law practice and he immediately made important connections to key powerbrokers in the territorial government. In 1866 he was appointed to serve as District Attorney for the Third Judicial District in Mesilla, yet not until the following year was he admitted to the bar. This backwards series of events was suggestive of his future political and legal doings in the territory.

By 1872, Catron had received appointment as U.S. attorney, and he used his post as a means of acquiring power and wealth. In New Mexico, wealth was measured in land. In order to increase his control over lands, most of which were apportioned as Spanish or Mexican Land Grants protected under the provisions of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Catron needed connections to powerful people in the territorial power structure. The shadowy Santa Fe Ring provided precisely the types of ties that he coveted.

In 1860 Congress established the legality of Spanish and Mexican Land Grants in its settlement with Juan Bautista Vigil and his claim to one such grant. To address the problem of overlapping claims and contested boundaries, Congress also established the Office of Surveyor General for the territory. The Surveyor General was to investigate disputes and offer solutions that would then require approval from the General Land Office and, finally, Congress itself. As with most other territorial offices, that of Surveyor General was an appointed position subject to the whims of patronage politics. Quite often, the Surveyor General was under the thumb of the Santa Fe Ring.

Under Spanish and Mexican administration, the grants had established a form of common-property land tenure. Under U.S. law, however, land claims were based on private-property forms of ownership. Despite the provisions of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and Congress’ settlement of Vigil’s claim, that key difference in legal recognitions of land tenure provided an opening for litigation that dispossessed New Mexican land grant heirs of their claims. When litigation against a particular grant was filed, the heirs typically did not have a strong enough command of the English language or the U.S. legal system to represent themselves in court. At that point, lawyers like Catron stepped in and promised to serve as counsel for the grantees. In a few noted cases, such as that of the Mora Grant, Catron disingenuously promised them that they needed to “temporarily” transfer their deeds to him in order for him to secure their grants. In other cases, land was the only means of payment available to the grantees.

By the end of his life, Catron acquired at least partial interest in no fewer than thirty-four different land grants. For a time, he owned more land than any other single person in the United States. His connection to the Maxwell Land Grant in north central New Mexico and the Carrizozo Ranch in Lincoln County highlight the ways that affiliates of the Santa Fe Ring promoted organized violence to acquire property and protect their interests. In the cases of the Colfax County (1875) and Lincoln County (1878) Wars, Catron, Elkins, and other prominent Ring affiliates did not directly commit acts of violence. In fact, they never did. Instead, others who hoped either to capitalize on their connection to the Ring or who stood in opposition to the political machine fought the battles.

Interestingly, the Santa Fe Ring, the Colfax County War, and the Lincoln County War were natural outgrowths of the attempt to establish American-style capitalism in New Mexico. The national and international press tended to paint the territory as a lawless place dominated in the 1870s and 1880s by bandits like Billy the Kid. By most reports, the accused bandits on horseback bore the blame for perpetuating lawlessness and violence. Their actions certainly did nothing to alleviate the situation, but the reality was that those who were supposed to bring law and civilization to the territory actually intensified its violent and unsettled conditions. Modernization, manifested as capitalist, private ownership of land and resources, compounded corruption and violence.

The Maxwell Land Grant was the linchpin of troubles in and around Colfax County. In 1864, Lucien B. Maxwell bought out all other heirs to the grant, most of whom were his in-laws, in order to become its sole owner. After only three years he decided to sell the tract and he requested a survey in order to determine its exact boundaries. Congress’ 1860 decision in a claim against the Ramón Vigil Grant upheld the provision of Mexico’s 1824 Colonization Law that limited individual grants to 97,000 acres. The Maxwell Grant was therefore set at 97,000 acres in size.

None other than Catron served as Maxwell’s legal advisor in 1869, and he persuaded the grant holder to sell to a group headed by Colorado politician Jerome Chaffee. Subsequently, Chaffee’s group created the Maxwell Land Grant and Railway Company to administer the grant, with Stephen Elkins as its president. With deed to the tract in hand, the Company hired W. W. Griffith, U.S. deputy surveyor, to conduct a new survey. Griffith’s survey redrew the tract at 2 million acres—a claim more than ten times the size of the original survey’s decision. Over the next few years, as the Company hoped to capitalize on the expansion of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad, they attempted to sell the property at a large profit to English investors. By the time competing survey claims finally established the tract at 1.7 million acres, the British syndicate had collapsed. In the spring of 1879 Catron himself purchased the massive tract for a vastly reduced price.

As all of the wrangling over the size and ownership of the grant played out, homesteaders attempted to stake their own claims. In many cases, they built homes, barns, and fences on lands they believed to be adjacent to the Maxwell Grant. Jicarilla Apaches, nuevomexicanos, and Anglo miners had long inhabited the region. Most had amicable relations with Lucien Maxwell. He understood the reciprocal responsibilities that a traditional patrón provided to those that lived on and near his lands. Inhabitants of the area were indebted to him for their place on the land, but they also relied on routines and norms that had never been guaranteed on paper.

Courtesy of Philmont Museum-Seton Memorial Library, Cimarron, NM

The Maxwell Land Grant and Railway Company and the English syndicate, however, relied on deeds and other tangible evidence of their right to transform the patterns of life that had long existed on the grant. As a private property regime worked to replace communal systems, conflicts erupted that resulted in murders and patterns of vengeance. No longer could locals expect redress from their patrón. Absentee company officials made decisions that impacted their access to vital resources without their input. Additionally, dissenting members of the Company began to resent the influence of the Santa Fe Ring. William R. Morley and Frank Springer emerged as the most prominent among them.

Palpable tensions erupted into violence over a seemingly petty matter in April of 1875. Catron charged Ada Morley, William’s wife, with mail fraud because she intercepted a letter that her mother had mailed at the Cimarron post office. Her mother, Mary Tibbles McPherson, noticed the cycles of corruption that marked territorial dealings during a visit from her home in Iowa. The letter was a denunciation of such activities to Washington officials. Catron tenaciously pursued what most locals considered to be an unjust prosecution of Ada Morley.

In the process another opponent of the Ring, Reverend Franklin J. Tolby, became increasingly more vocal. On the morning of September 14, 1875, as he traveled back to his home at Cimarron after completing worship services in Elizabethtown, an unknown attacker shot him twice in the back. His murder shocked the local community, and his friends and family members held partisans of the Santa Fe Ring responsible.

As the investigation played out, some of Tolby’s friends vigorously questioned and then murdered Cruz Vega, the regular letter carrier between Elizabethtown and Cimarron, for his alleged complicity in the killing. From Vega, they learned of others who had been involved in the reverend’s murder. Several were reportedly connected to the Santa Fe Ring. The last shots of the Colfax County War rang out in November after Manuel Cárdenas, an associate of Vega, testified that men with purported ties to the Ring had ordered Tolby’s murder. As he was transported away from the courthouse, Cárdenas was killed from ambush.

In an attempt to calm the situation, Governor Samuel Axtell ordered troops from Fort Union to maintain order in Cimarron. Yet Axtell was a known friend of the Ring so his actions, as well as the decision early in 1876 to attach Colfax County to Taos County for judicial proceedings, indicated how pervasive the power of the political machine had become. To many locals, the killings indicated just how far the territorial political machine was willing to go in order to control wealth and power in Colfax County.

The events of the Lincoln County War are more widely known, and more heavily romanticized, due to the involvement of Billy the Kid. In the 1860s, 1870s, and 1880s, Lincoln County comprised nearly the entire southeastern quadrant of New Mexico Territory. Sheep-herding and cattle ranching dominated all other economic pursuits, and contracts to deliver cattle to reservations, such as Bosque Redondo, proved quite lucrative.

Irish immigrants Emil Fritz, Lawrence G. Murphy, and James J. Dolan built a commercial empire in Lincoln based on the success of their government contracts at Fort Sumner and Fort Stanton (the Mescalero Agency after 1865), and Murphy and Dolan’s L. G. Murphy & Company held a commercial monopoly over Lincoln County. With their stranglehold on the economy came virtual control over the county’s government and political systems. Indeed, their operation was known to locals simply as “the House,” named for their imposing headquarters in Lincoln.

The mid-1870s brought perilous times for the House as several of its banking, mercantile, and ranching enterprises began to falter due to a nationwide economic downturn. In order to salvage the businesses, Murphy and Dolan secured loans from Catron. His loan of $20,000 saved part of the Murphy-Dolan empire, but a few of their holdings reverted to Catron when they failed to return to profitability. The store in Lincoln, some tracts of land, horses, hay, grain, and cattle herds, along with a tract near Roswell, were among them.

Such business dealings convinced residents of Lincoln County of the close ties between the House and the Santa Fe Ring. Once again, evidence of the Ring’s activities came through those who were most vocally opposed to it. In the case of Lincoln County, the opponents were John H. Tunstall, a London native who arrived in the United States in 1872 looking to make a fortune, and Alexander A. McSween. Tunstall made no secret of his ambition to grab as much land as possible in the West. He hoped to control a ring of his own. Indeed, Murphy and Dolan’s grip on Lincoln County was something he envied.

McSween was a lawyer who had worked as bill collector for the House before throwing his support behind Tunstall. Little of McSween’s personal life prior to his move to Lincoln is known, but he and his wife Susan arrived in Lincoln in 1873. His ties to the House fell apart, however, following the death of Emil Fritz in June of 1874. Tasked with collecting Fritz’s $10,000 life insurance policy, he traveled to New York in the fall of 1876. After paying fees on the policy and subtracting his own expenses, only about $3,000 remained. Rather than turn the money over to Murphy and Dolan, McSween deposited it in his personal account.

During McSween’s trip back east, in February of 1877, Tunstall had arrived in Lincoln and acquired land on the Rio Feliz. The following summer he opened up a mercantile in town in direct competition with the House. Those actions alone were enough to gain the ire of Murphy and Dolan, yet Tunstall hired McSween to represent him in legal matters. In order to chip away at the brash Englishman’s gains, Murphy and Dolan persuaded Fritz’s heirs to charge McSween with embezzlement. As a result, McSween was arrested and he appeared before Judge Warren Brisol and District Attorney William L. Rynerson, both known associates of Catron.

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Legal proceedings against McSween carried on between February and April 1877. Sheriff William Brady, a reliable associate of the House, carried out the Bristol’s decision to confiscate McSween’s property to pay the $8,000 bail. Like most Lincoln residents, Brady assumed that McSween and Tunstall were partners so he took control of the Tunstall store as well, the total far exceeding the $8,000 figure. Then, he moved to confiscate the Englishman’s cattle along the Rio Feliz.

McSween was a man who abhorred the House and wished to erode the power of Murphy and Dolan, but he equally abhorred violence. He never carried a gun, despite living in a time and place in which most people did. Tunstall, on the other hand, was not shy about the use of violence to achieve his ends. Although he dressed and spoke differently than most locals, anyone not aligned with the House tended to like him because they hoped that he could bring down Murphy and Dolan.

Tunstall therefore hired ranch hands that were not only hard workers, but who could also fight and handle a pistol. In the fall of 1877 an eighteen-year-old known then as Billy Bonney joined his payroll. Billy was born Henry McCarty, probably in New York, although some writers have variously posited his birthplace as Ohio, Illinois, or Indiana. Some have said that his birthdate was November 23, 1859, but that point has not been verified either. It is known that he moved with his mother, Catherine McCarty, to New Mexico territory where she married William H. Antrim in 1873. Catherine died of tuberculosis in the fall of 1874 in the family’s new hometown of Silver City.

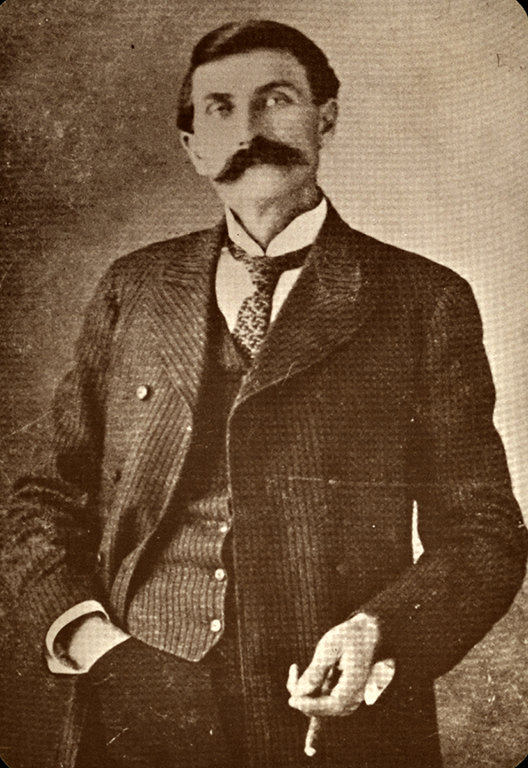

Courtesy of Library of Congress

After his mother’s death, accounts differ about young Henry’s stepfather. Some suggest that William Antrim was hardworking, but largely absent from his stepson’s life. Others indicate that the stepfather abandoned Henry. Although he had seemingly loved his life in Silver City, attending fandangos with the town’s Spanish-speaking residents and gaining a reputation for his charm, he fell into trouble and eventually made his way to Arizona and then to Lincoln County. By the time he found work with Tunstall, Billy was known by several aliases, including Kid Antrim and Billy Bonney. Not until his association with the violence of the Lincoln County War did he earn the moniker Billy the Kid.

Billy developed an intense level of respect and loyalty for Tunstall who, at the age of twenty-four, was just a few years his elder. After all, Tunstall was the first person to give Billy a legitimate chance to settle down and make a living. Billy joined others under the employ of Tunstall along the Rio Feliz in February 1878 to defend their employer’s cattle, and over the course of several days the Tunstall faction had several gunfights with members of Sheriff Brady’s posse. Then, on the evening of February 18, Brady’s deputy Billy Matthews and a few others encountered Tunstall and shot him down.

Matthews and Brady claimed that Tunstall was killed because he resisted arrest. Given the ongoing conflict between the two sides and the shaky legal ground that Brady used to justify his actions, however, most historians agree that Tunstall was murdered in cold blood. Billy certainly felt that way. Tunstall’s murder intensified the feud between the House and its enemies and initiated the Lincoln County War.

Over the course of the spring and summer of 1878, Billy led Tunstall’s men, known as the Regulators, against associates of the House and Sheriff Brady. Based on McSween’s experience with territorial and local authorities, the Regulators believed that there could be no justice in Lincoln County unless they made it for themselves behind a gun. Although Murphy and Dolan continued to back their network of gunslingers, their financial woes had worsened in early 1878. Strapped for cash, they mortgaged land and property, including the Carrizozo Ranch, to Catron for $25,000. As fighting intensified, Dolan dissolved the House and Murphy fled Lincoln and subsequently died in October of 1878 of alcohol-related complications.

Violence hit its crescendo in July. Between July 14 and 19, Regulators holed up in the Tunstall store, and then the McSween house, as open gunfire rattled the streets of Lincoln. In scenes that have been embellished and made legendary in films such as Chisum and Young Guns (among others), McSween ended up dead in the center of town and his house burned to the ground. During the “big killing,” as that week in July came to be known, Billy rose to prominence as the primary leader of the Regulators. Although the most intense fighting in Lincoln had come to a close, he helped the Regulators escape Dolan’s men, soldiers, and law officers for the next couple of years.

Courtesy of Buckner/Garrett Photograph Collection, New Mexico State Records Center and Archives (#55249)

New Sheriff Pat Garrett located Billy the Kid at the Maxwell residence at Fort Sumner in July of 1881, after the fugitive endured a broken promise of amnesty from the territorial governor, court appearances, and a bold escape from the Lincoln jail. Other Regulators had fled the territory, but Billy remained behind. Most researchers believe that he refused to flee because he was in love with Paulita Maxwell, daughter of Lucien Maxwell. Her brother, Pete, did not approve of the relationship, and he alerted Garrett of Billy’s presence at Fort Sumner. In the dead of the night, Garrett took Billy by surprise as he went to cut himself a slab of beef on the Maxwell’s porch. Realizing that he was not alone, an alarmed Billy pulled his pistol and repeatedly asked “¿Quién es?” (“Who is it?”) in the dark. No answer came except for the bullet from Garrett’s gun that killed him.

Billy the Kid looms large as a legend of the Wild West, and he has come to mean many different things to different groups of people since his short lifetime. Numerous authors and filmmakers have alternatively sought to find the man behind the myth or to advance legends about the Kid. While he was still alive he became something of a hero to nuevomexicanos and Mescaleros in Lincoln County. He spoke fluent Spanish and he challenged a legal and economic system that threatened to dispossess both groups of people of their lands and resources.

Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 105450

Following his partner’s death, Dolan continued the enterprise in Lincoln although the power of the House was forever diminished by the Lincoln County War. Susan McSween lost her husband, but was able to rebound and gain a reputation as the “Cattle Queen of New Mexico.”26 For his connections to the conflict that came to light during federal investigations of the events in Lincoln, Catron lost his position as U.S. Attorney. Yet he retained the land and property he had acquired from Murphy and Dolan, and his nefarious Santa Fe Ring remained intact.

Historian Kathleen P. Chamberlain has argued that Catron did not “truly represent the forces of modernization” because “his own interests often dominated to the detriment of the territory.”27 If we see modernization as the events and trends that solidified the hold of capitalism, private property, and U.S. party politics on the territory, however, Catron was instrumental in the modernization of New Mexico. Although it is easy to take modern systems of economics and governance for granted, many scholars have emphasized the reality that various processes of “creative destruction” or “original accumulation” must destroy former ways of regarding things like land tenure or economic exchange to open space for their successors. Violent events like the Colfax and Lincoln County Wars were part and parcel of that process.

Territorial status structured all political, economic, racial, and social interactions in New Mexico between 1848 and 1912. Miguel A. Otero, Stephen B. Elkins, and other delegates to the U.S. Congress understood that their principal duty was to negotiate support for statehood. Before any real progress toward that end could be made, however, Congressmen and other powerful Easterners sought evidence that New Mexico territory was a modern, American place. Terms like “modernization” and “Americanization” lack precise and consistent definitions; they are largely subjective. Yet in the late nineteenth century, both were tied up in the notions of capitalist economic systems, the rule of U.S. legal precedents, speaking the English language, and adherence to the Christian faith.

Bishop Jean B. Lamy arrived in New Mexico for the express purpose of normalizing and Americanizing Catholic practices in the Territory. Yet as was the case in attempts to militarize the territory, remove its indigenous peoples, and assert new modes of land tenure, nuevomexicano Catholics pushed back. As in the earlier period of Spanish colonization, American colonization of New Mexico inspired much resistance. Measures intended to stamp out the territory’s dominant cultures were never fully successful. As we will see in the next few chapters, attempts to modernize and Americanize New Mexico Territory came in various cultural and entrepreneurial forms. In response, nuevomexicanos and indigenous groups found unique means of resistance and cultural resilience.