As a unique nuevomexicano society took shape along the Rio Grande corridor, power relations among the region’s nomadic peoples shifted. Inspired by their prowess on horseback, Utes expanded their territorial control into Navajo lands in the San Juan Basin in the early 1700s. Their presence also threatened New Mexican settlements. As had been the case since the arrival of the Coronado entrada, independent indigenous peoples vastly outnumbered those loyal to the Spanish crown.

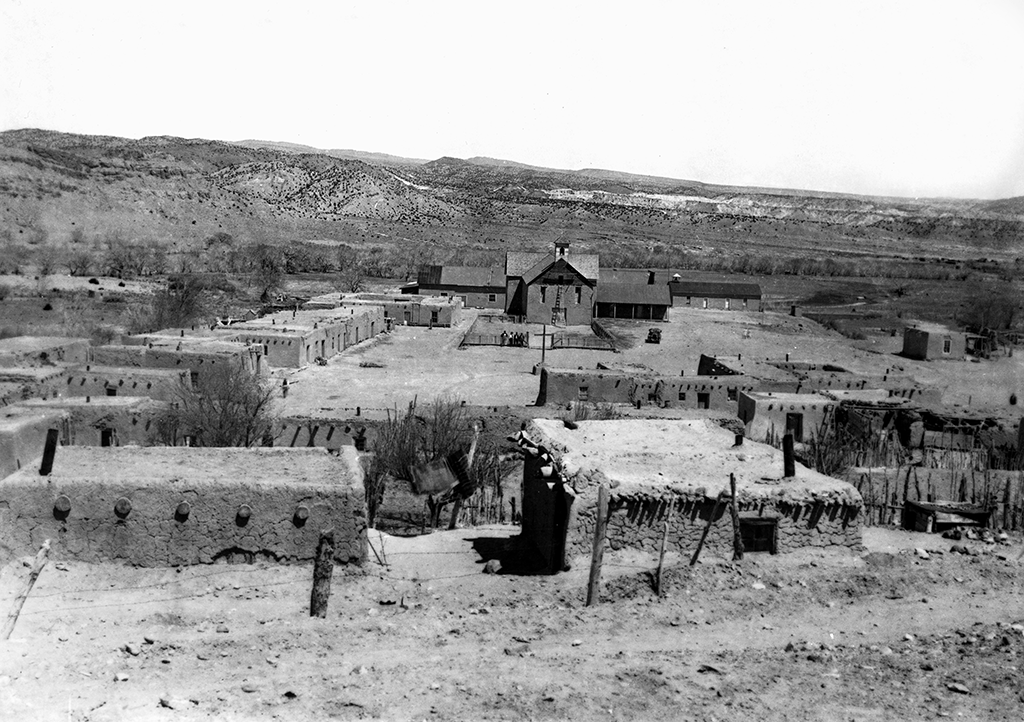

Social, political, and economic life in New Mexico was shaped by the demographic disparity. In 1716, Ute warriors attacked Taos. Abiquiú, a small community of about twenty families that had developed along the Chama River during the late 1730s, endured frequent Ute and Navajo raids. In 1747, a combined Ute and Comanche attack forced the settlers to abandon their homes. Three years later, Spanish authorities in New Mexico backed the resettlement of the community a few miles upstream at its present-day location. Many of those who resettled Abiquiú were genízaros from the areas of Santa Fe and Santa Cruz de la Cañada.

Within the context of ongoing violence, in the summer of 1750 a contingent of nearly 130 Comanche men arrived on the outskirts of Taos looking to trade. Despite misgivings that the traders posed a threat, Governor Tomás Vélez Cachupín allowed a trade fair to transpire. Cachupín, who had taken office the previous year, recognized that existing policies had done nothing to quell conflict and instead had left the colony economically broken. He advocated a program of diplomacy, noting that nomadic peoples “must be ruled more with . . . policies of peace than those which provoke incidents of war.”1

Pragmatically, Cachupín also warned the Comanche traders that any raid or attack, no matter how minor, would be an act of war. Although the warning dissuaded the traders from violence, in November a separate Comanche band led a daring raid against Pecos. At the head of an army raised from the presidio of Santa Fe, Cachupín engaged the Comanches far to the east in what later became known as the Battle of San Diego Pond. Aided by the element of surprise, the nuevomexicano forces subdued their opponents after a bitterly cold afternoon of bloodshed. Forty-nine Comanches surrendered and Cachupín’s men captured over 150 horses and mules. All of the others perished.

That episode solidified the governor’s resolve to realign ties between the New Mexico colony and the various nomadic peoples that surrounded it. Recognizing the developing state of conflict between Ute and Comanche bands, in 1752 Cachupín spearheaded a peace arrangement with a group of Ute headmen. Over the next few decades, the alliance with the Utes helped to diminish the threat of Comanche attacks. Pleased with the results, Cachupín noted that “the friendship of this Ute nation and the rest of its allied tribes is of the greatest consideration because of the favorable results which their trade and good relationships bring to this province.”2

New trade outposts sprang up in the areas beyond principal New Mexican settlements, like Galisteo, Pecos, Santa Fe, and Taos. Despite economic and military ties to Ute allies, such places continued to face the specter of periodic Comanche and Navajo raids. Somewhat paradoxically, the trade that transpired at outposts like Abiquiú also contributed to increased violence. Trading posts were particularly attractive to certain groups of Comanches and Navajos. Bloody contests between settlers and nomadic peoples were all too commonplace between 1750 and the 1770s.

Not content with the state of affairs, Governor Cachupín, in 1754, established a schedule of protocols and prices to govern trade fairs between settlers and Comanches at Taos. He recognized that, despite the devastation that was often wrought through raiding, the New Mexico colony’s fragile economy depended on the Comanche presence at the annual trade events. Due to a lack of currency in New Mexico, the pricing arrangement established equivalencies between common New Mexican commodities and goods that Comanches typically brought to exchange. By the mid-eighteenth century, Comanche wares included traditional items, such as buffalo hides, supplemented by ammunition, arms, and other finished goods acquired from French traders.

Cachupín’s combination of pragmatism and military prowess earned him a reputation among the Comanches as the “captain who amazes.”3 Despite his best efforts, however, the New Mexico colony floundered throughout the eighteenth century. Nomadic raids, coupled with a lack of transportation to and from the colony (the Camino Real was the only official trade corridor), contributed to the problem. As difficult as those issues were, a crisis beyond the governor’s control exacerbated matters. The economic and political decline of the Spanish Empire on a global level also meant that the isolated colony received little if any, support.

As this brief account of Cachupín’s tenure illustrates, during the eighteenth century, nuevomexicanos united in confronting the problems of violent raids, economic decline, and social discord. By the 1780s, new leadership in Madrid took measured steps to reverse the overall decline of the Spanish Empire in the form of legislation that has since been known as the Bourbon Reforms. In New Mexico, the Bourbon Reforms, although imperfect, created the conditions for a lasting peace with Comanches, Navajos, and Utes that began in 1786 and lasted until Mexico gained its independence from Spain in 1821. During the period of peace, unique expressions of cultural and religious life emerged in New Mexico.