The History of New Mexico

Collapse

Expand

-

Chapter 4: Spanish Colonization of New Mexico, 1598-1700

- Spanish Colonization of New Mexico, 1598-1700

- Toward New Mexico

- Oñate & Initial Spanish Colonization

- Oñate's Troubled Tenure

- Building a Royal Colony

- "The First American Revolution"

- References & Further Reading

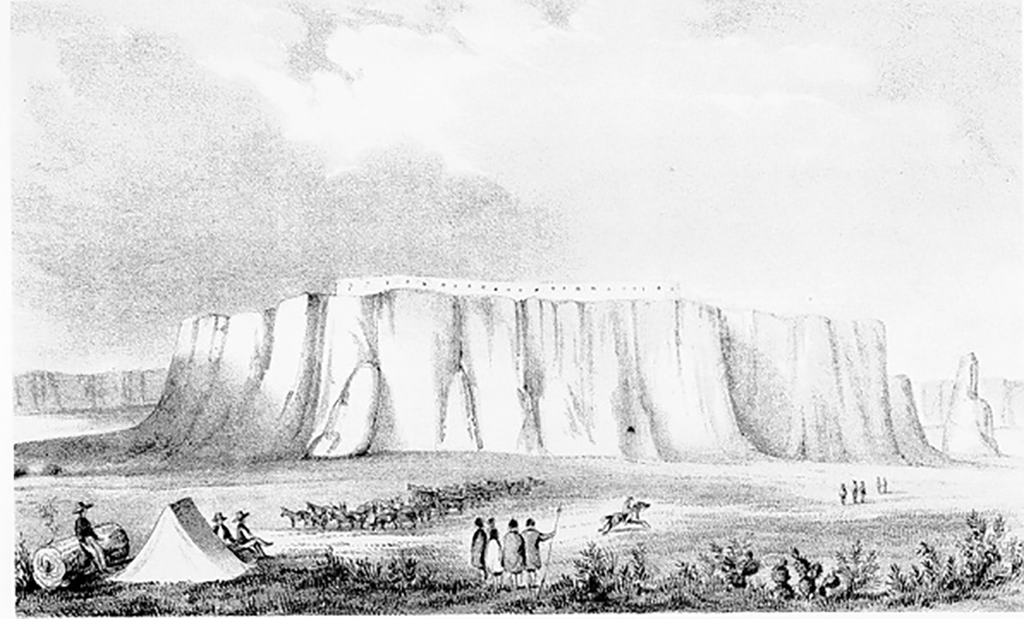

Conflict with Pueblo peoples and the isolation of the Spanish colony from other points in New Spain defined Oñate’s tenure as governor. By the fall of 1598 he initiated a tour of the pueblos in order to further solidify the Spanish hold over the colony. In late October, he took oaths of allegiance from leaders of Acoma Pueblo. He seemed unaware that the Acoma people had invited him there in order to kill him. Atop the 365 foot-high mesa that housed their community, some Acomas attempted to lure him into one of their kivas where a number of armed warriors waited to ambush him. Not completely trusting of the Acoma, Oñate declined the tour at the behest of his men.

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

After unwittingly escaping the Acoma plot, Oñate set out on a mission to locate the Pacific. A heavy snowfall prevented the governor from completing his journey, and as his group made their way back toward San Juan they received word that Oñate’s nephew, Juan de Zaldívar, had been killed at Acoma along with others under his command. Furious at the news, he returned to San Juan where he learned the details of the skirmish. Survivors of the battle reported that Acoma warriors approached their camp to invite Zaldívar and a few others to tour the pueblo. Once atop the mesa Zaldívar’s group initiated trade for food, as was their usual practice. Without warning, Acoma warriors attacked and then tossed the bodies of Zaldívar and his twelve companions off of the mesa toward the rest of the party. The frightened survivors fled in three groups to warn the colonists at San Juan, the Franciscans in their missions, and to report the attack to Oñate.

Unfortunately for Pueblo peoples elsewhere in New Mexico, the Acoma Revolt (as the Spaniards referred to the incident) created an atmosphere of fear and apprehension toward all natives. When Oñate returned to San Juan, he found a heavily armed guard around the settlement. Oñate called a council of war to consider what action to take. Above all, Oñate and his advisors recognized that they were greatly outnumbered by the pueblos. Such had typically been the case for Spanish explorers and conquistadors. The established practice was to divide and conquer native peoples by finding and exploiting existing divisions and antagonisms between them. Also well-established was the use of “display violence or the theatrical use of violence” that enhanced the weight of the performances discussed above.4 Oñate understood that through a display of violence, he could assert Spanish dominance in an isolated place where the colonists were in the minority.

Much historical debate has surrounded the Acoma Massacre or Battle of Acoma Pueblo that took place in January 1599. The mere fact that it is remembered by so many different titles illustrates this point. Depending on perspective, the violent skirmish was viewed alternately as a “Revolt” (Spanish perspective) or a “Massacre” (Acoma perspective). Additionally, modern interpretations of the event have either taken one of these two sides or used the term “battle” in an attempt to be more objective. The recent work of historians and anthropologists has recognized the capacity of language to tilt the balance of power. Some even argue that words themselves can enact violence. The description that follows attempts to take these multiple and varied perspectives into account.

After much discussion at San Juan, Oñate elected to allow Vicente de Zaldívar, brother of the fallen Spanish leader and another of his nephews, to lead the assault against Acoma. Although vengeance certainly motivated the Spaniards, Oñate’s orders to his nephew illustrate his recognition of the Spaniards’ tenuous position in New Mexico. His response to the events at Acoma was calculated to enhance the ability of the colony to thrive in the midst of tens of thousands of potentially hostile Pueblo peoples. He instructed Zaldívar to position his men for battle upon their arrival at Acoma, but to first “summon the Indians of Acoma to accept peace once, twice, and thrice, and urge them to abandon their resistance, lay down their arms and submit to the authority of the king, our lord, since they have already rendered obedience to him as his vassals.”5

According to reports of those in his company, Zaldívar complied with his uncle’s orders. After extending the invitation to a peaceful return to Spanish subjection on January 21, 1599, he asked that the warriors responsible for the attack be handed over to him. He assured the Acoma people that they would “be justly dealt with.” At that point, he assessed the situation before taking further action. If the Acomas’ strength appeared too strong, Oñate had advised him not to commence an attack. If he appeared to have any advantage, Oñate’s instructions were to “punish all those of fighting age as you deem best, as a warning to everyone in this kingdom.” The governor was clearly concerned with the colonists’ ability to maintain control over the region. He additionally ordered Zaldívar that if he should see fit to show mercy to the Acomas following the battle (he assumed that the Spaniards would be victorious), “you should seek all possible means to make the Indians believe that you are doing so at the request of the friars with your forces. In this manner they will recognize the friars as their benefactors and protectors and come to love and esteem them and to fear us.”6

Despite some calls for negotiation, Acoma’s leaders readily dismissed Zaldívar’s demands and he moved his soldiers into positions on two opposite sides of the pueblo. Their taunts and insults struck fear into the hearts of many of the Spanish troops, as Pérez de Villagrá later reported. Spaniards recalled that during the night following their arrival, the Acoma people engaged in “huge dances and carousals, shouting, hissing . . . challenging the enemy to fight.”7 The army’s interpreters also reported that they vowed to go to war against the Keres, Tigua, and Zia people due to their collusion with the colonizers. The Acoma warriors’ attitude toward other local peoples illustrates the often deep divides between the various groups that the Spaniards’ collectively called the Pueblos.

“You shall seek all possible means to make the Indians believe that you are doing so at the request of the friars with your forces. In this manner they will recognize the friars as their benefactors and protectors and come to love and esteem them and to fear us.”

– Juan de Oñate

On the morning of January 22, Zaldívar once again demanded that that Acoma people surrender unconditionally. This time his request was met with a volley of arrows. Zaldívar withdrew his forces and waited until about three o’clock that afternoon to commence the assault on the pueblo. His strategy worked: the Acoma warriors focused on the soldiers that ascended the main ladders toward the pueblo above, completely ignoring the backside of the bluff. A small group of Spaniards hoisted a small cannon toward the pueblo from the rear. The first day of battle ended with the surrender of many of the Acoma people, although many warriors held out by hiding in the surrounding caves.

As the fighting continued into its second day, Zaldívar realized that the Acoma warriors were killing women and children rather than have them fall prisoner to the Spaniards. Accordingly, he issued orders that his men capture as many of the women and children as possible in order to prevent their deaths. By midday, he ordered his men to proceed with no quarter. The Spaniards set fire to all of the Acoma peoples’ homes and belongings. Not until the next day did the last of the warriors surrender. According to the Spaniards’ estimates, about eight hundred Acoma people lay dead. None of the Europeans had been killed, and only a few had been wounded.

Reportedly, all of the survivors, about five hundred total, were taken to Santo Domingo to stand trial. It had been estimated, however, that somewhere around 6,000 people were living at Acoma in 1598. Many of Acoma’s people were able to escape the Spaniards’ wrath, although their town had been leveled during the fighting. At Santo Domingo, the prisoners were charged with the murder of Juan de Zaldívar and twelve others. Captain Alonso Gómez Montesinos received the appointment to represent the defendants during their hearing, which ultimately lasted three days. Gómez Montesinos performed his task to the best of his ability, and he petitioned for the release of several prisoners that had not been present at Acoma on the day of the initial attack on Zaldívar and his men. Several other colonists also pleaded for leniency.

Yet, holding to his conviction that a show of force had to be made against the people of Acoma, Oñate issued an incredibly harsh sentence. All of the men over the age of twenty-five were condemned to have one foot cut off. They were then to serve select Spaniards for a period of twenty years. Men between the ages of twelve and twenty-five and women older than twelve were also sentenced to twenty years of labor. Children under the age of twelve were placed in the charge of the Franciscans.

Courtesy of Dorothy Sloan Rare Books

In recent years, historians have debated whether or not the mutilations actually occurred. Documents indicate that the punishment was later limited to twenty-four Acoma warriors, rather than applied to all men over twenty-five years old. Yet, no evidence of the act itself remains in the historical record. Whether or not the sentence was carried out, Oñate’s goal was clear. He used intimidation to force the submission of much larger groups of indigenous peoples. Significantly, he was required to use brutal methods to suppress the Tompiro people in 1601.

Much of the rest of Oñate’s tenure in New Mexico was occupied with exploration missions and the continuance of intimidation through violence. Shortly after the trial of the Acoma prisoners, he relocated the capital of New Mexico across the Rio Grande to the Tewa Pueblo of Yúngé. His methods of coercion seemingly worked in the short term because the Yúngé people offered no resistance to the Spanish occupation of their homes. Most of them relocated to San Juan, and Oñate renamed the new capital San Gabriel. The move also illustrates Oñate’s strategy to prevent further violence between the colonists and the pueblos. He hoped that by placing distance between the groups, he would be able to build a strong Spanish colony in the midst of overwhelmed natives.

His dreams were short lived. Although the colonists knew that New Mexico did not promise quick riches, most were not prepared for its isolation, rugged topography, and arid climate. Even with the promise of encomienda, survival was a constant struggle for a group of people that was used to milder climates and fertile soil. By the spring of 1601, word reached Viceroy Velasco that many of the colonists, specifically a group of seventy-three settlers that reached New Mexico in December 1600, “complained that they had received reports, information, and letters, telling of much greatness and riches, and that they had been defrauded.”8 Many had given up prosperous estates in order to join the new colony. They reported that food and clothing were always in short supply in New Mexico, despite Oñate’s promises to the contrary.

Oñate’s near-constant exploration journeys added fuel to the fire. In the fall of 1601, while the governor was away on an expedition to locate the fabled city of wealth known as Quivira, about two-thirds of the colonists (four hundred or so) fled the province. Their decision was significant because desertion was considered a crime punishable by the loss of title and prestige, and, in certain cases, death.

In November 1601, following his unfruitful journeys in the Great Plains, Oñate returned to San Gabriel to the news that most of his colony had deserted. In this instance, his brutal methods were not directed toward Pueblo peoples. As was his character, he moved quickly to prevent the entire failure of the venture in which he had invested his life and material possessions. He issued a sentence of death by beheading for the leaders of what he deemed to be a mutiny, and he sent Vicente de Zaldívar to return them to New Mexico. Zaldívar, however, found that the group had already reached safety and royal protection far to the south in Nueva Galicia. Instead of returning the deserters, Zaldívar spent the next few years working to defend his uncle against charges of abuse against both native peoples and colonists, as well as the mismanagement of the colony.

Oñate’s governorship continued its downward spiral until he preemptively resigned in June 1606 in order to avoid impending removal by royal officials. The final years of his governorship witnessed further excursions against recalcitrant Pueblo peoples. In 1603, Oñate reportedly killed a Taos leader during an expedition to quash a rebellion there against Spanish domination. That murder was added to the long list of charges against him. In 1604, he led another excursion to the Gulf of California in search of the Pacific Ocean. In all, his calculated violence against Spaniards and Pueblos alike and his absenteeism left New Mexico on the verge of abandonment in 1607. Only a few hundred colonists and a handful of Franciscans remained in the desolate far northern frontier. Although Oñate was able eventually to clear many of the charges against him, he was unable to reverse the sentence of lifetime banishment from the New Mexico colony.