In June 1527, a group of about five hundred Spaniards under the leadership of Pánfilo de Narváez set out from the port of Cádiz, Spain, to explore an area known in their collective imagination as La Florida. After crossing the Atlantic and stopping at several points in the Spanish Caribbean, the group made landfall on the western coast of Florida.

Panfilo de Narváez’s Route from Cádiz

The Narváez expedition set out from Cádiz, crossed the Atlantic, and was shipwrecked on the western coast of Florida. Ultimately, Narváez and most of the expeditionaries lost their lives. Only Álvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca and three others survived the ordeal.

By that time, only about two-thirds of the initial force remained. Narváez’s express goal was to subdue indigenous groups in the peninsula that were rumored to possess grand cities and great wealth, much like that of the Aztec Empire in central Mexico. He and his men may have even hoped to locate the fabled Fountain of Youth, which had been one of the targets of Juan Ponce de León’s earlier expedition to Florida.

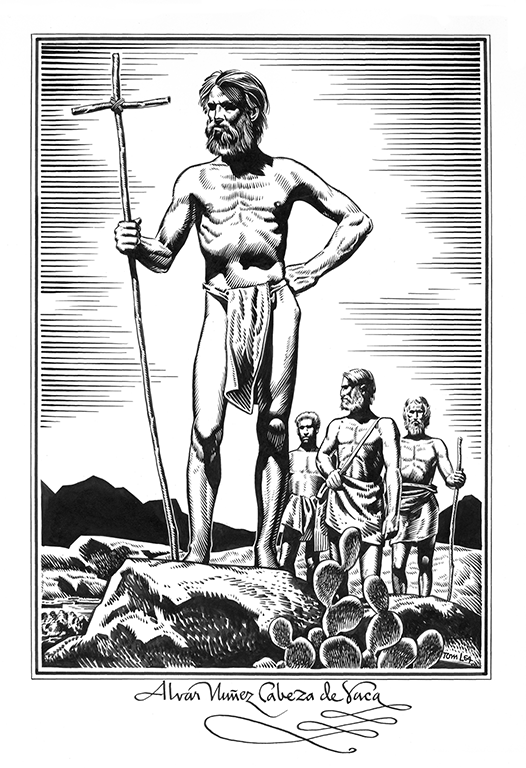

The party’s treasurer (tesorero) was an Andalusian man named Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca. Although he could have had no idea when he joined the expedition, tragic turns of events would lead him far afield from La Florida. Despite low levels of supplies upon their landing, Narváez marched the force inland to locate the Apalachee tribe. Rather than finding large cities lined with gold and silver, the expedition instead became lost. After months of battling hostile peoples (none of whom possessed items deemed to be of value to the Europeans) and illness, only 242 men emerged from the Florida swampland at the shores of Apalachee Bay.

In dire straits, in September 1528 the men built five makeshift rafts from horse hides and attempted to sail across the Gulf of Mexico to New Spain. One of the crafts was captained by Cabeza de Vaca. Due to murky understanding of the region’s geography, the Spaniards believed that the trip would be a quick jaunt. Instead, they were battered by the current of the Mississippi River and then caught in the throes of a hurricane. Three of the boats were lost, including Narváez’s “flagship.” The other two eventually washed up onto the shore of present-day Galveston Island, Texas. The forty survivors referred to the island as Malhado (Misfortune). Although the survivors attempted to salvage the rafts, they were carried out to sea by a large wave.

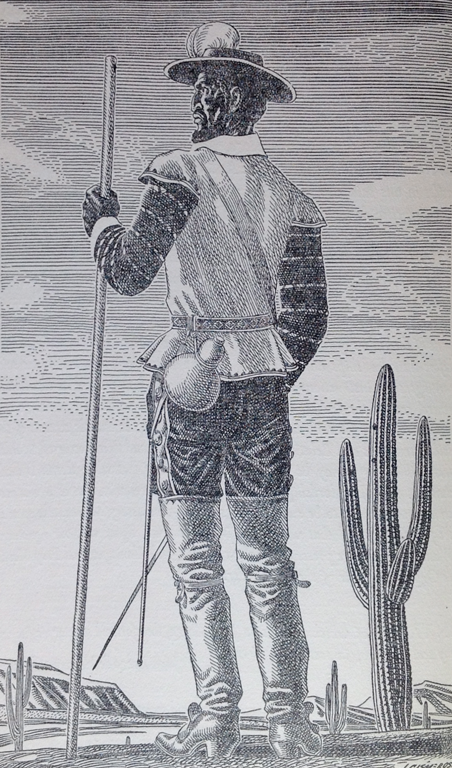

Local Cavoque and Han peoples soon captured the men and placed them in bondage. The Europeans passed as captives from one native group to another over the next few months. Unaccustomed to drudgery and difficult living conditions, many Spaniards contracted devastating illnesses and died. Six years later, only four survivors remained: Cabeza de Vaca, Andrés Dorantes de Carranza, Alonso del Castillo Maldonado, and a Moroccan slave named Esteban (also referred to by the diminutive “Estevanico” in some of the records). Esteban was the first known person of African descent to reach what became the continental United States. He had been sold into slavery in 1513 at a Portuguese trading port on the coast of his homeland. Although he was raised in the Muslim faith, many scholars believe that he had converted to Catholicism at some point because Muslims were not allowed to travel across the Atlantic. In 1520, Dorantes de Carranza bought him and later took him along on the harrowing Narváez expedition.

After such experiences, the group maintained an escort that, at times, included as many as six hundred indigenous allies as they made their way south toward New Spain. Cabeza de Vaca became convinced that if these people were to be converted to Christianity and Spanish ways of life, they would have to be persuaded through kindness, “the only certain way.” In early 1536, the party encountered a Spanish slaving expedition that escorted them south to Culiacán. Upon seeing the other Europeans, however, Cabeza de Vaca implored his native companions to flee. He understood all too well the brutal intentions of his countrymen. In his own words, he remembered looking out over an area that had been recently looted by the slavers: “With heavy hearts we looked out over the once lavishly watered, fertile, and beautiful land, now battered and burned, and the people thin and weak, scattering and hiding in fright.”2 As soon as Cabeza de Vaca had moved on, the slaving party captured and enslaved many of those that had accompanied him.

Upon their arrival in Mexico City the four survivors received a hero’s welcome. They had traveled 2,800 miles on foot and made contact with a variety of peoples in the far north. Although they never set foot in the territory that later became known as Nuevo México, they traded for copper bells which, as they understood, had originated at a great and lavish population center even further to the north. Such stories whetted the appetite of Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza who commissioned a reconnaissance party, led by Fray Marcos de Niza and Esteban, to investigate. Their findings led to the entrada (the Spanish term used to describe formal entry into new territory) headed by Francisco Vásquez de Coronado in early 1540.

Cabeza de Vaca’s Route

This map provides a rough estimate of the route followed by Cabeza de Vaca and his companions after their shipwreck in Florida. Although the group never set foot in present-day New Mexico, their tales of wealth and large-scale societies to the north inspired the entrada headed by Francisco Vázquez de Coronado in 1540

Cabeza de Vaca’s story is not only important to New Mexico’s histories because it spurred further Spanish exploration of the far north, however. His experiences provide a fleeting glimpse of an alternative pattern for Spanish-indigenous relations during the colonial period. As historian Richard White put it, “Cabeza de Vaca’s journey to this extraordinary world ends up in a very ordinary world, a world of Spanish slavers and Indian victims. But in between, in that moment, there was a vision of how something else might have happened. It never would really fully happen, but would appear in glimpses again and again as Indians and whites interacted in the continent.”3 Outnumbered and desperate, Cabeza de Vaca’s group initiated peaceful relations with natives. Rather than assuming their own physical and cultural superiority, they relied on native peoples for survival. In return, they learned to respect the peoples they encountered as human beings.

As Spanish explorers imagined a new Mexico in the far north after Cabeza de Vaca’s return, they thought in strikingly different terms. Although they faced many of the same issues, including the problem of being vastly outnumbered by indigenous peoples in an isolated land, they instead applied other patterns of Spanish exploration and conquest that had been in place since the time of the Iberian Reconquest (La Reconquista, circa 711-1492). Among these patterns, as outlined by historian Matthew Restall, were the “use of legalistic measures to lend a veneer of validity to the expedition,” “an appeal to higher authority” for legitimacy, focus on precious metals, large societies, the use of native allies to divide and conquer, the location of interpreters, and “the use of display violence, or the theatrical use of violence.”4