The History of New Mexico

Collapse

Expand

-

Chapter 14: World War II Era: Manhattan Project & Growing Federal Presence in New Mexico

- World War II Era: Manhattan Project & Growing Federal Presence in New Mexico

- World War II

- Manhattan Project

- Site Y

- Testing the Bomb

- Impact on Local Communities

- References & Further Reading

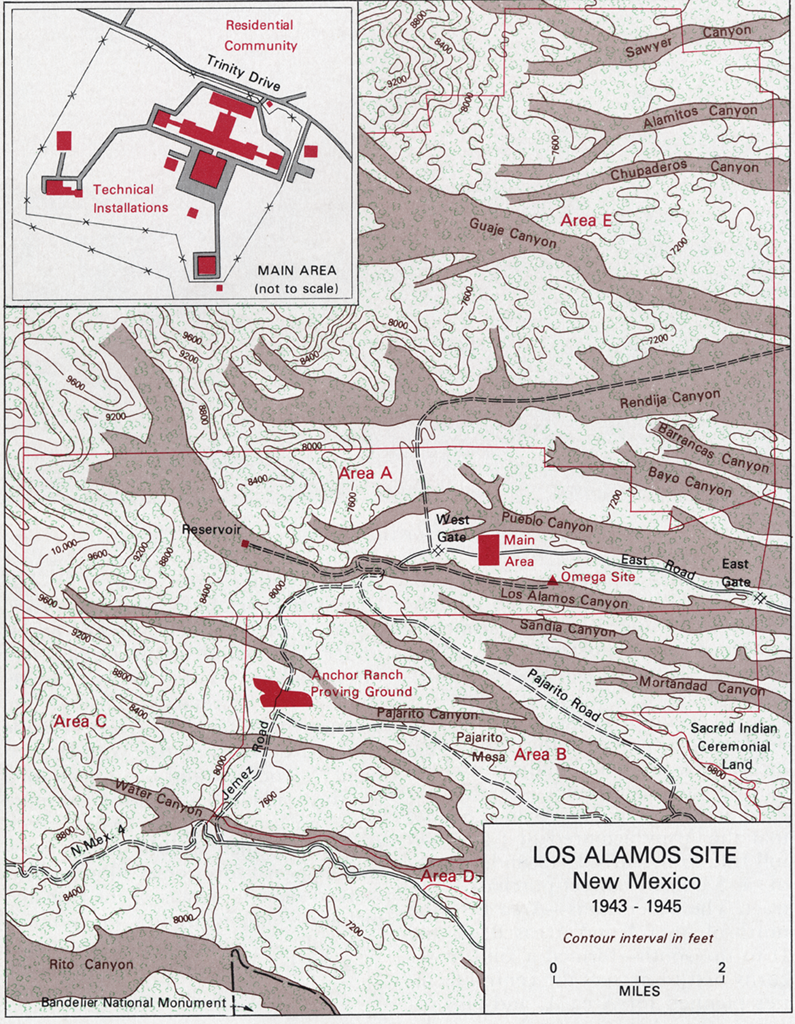

In early 1943, the town of Los Alamos did not exist. In fact, it did not appear on any maps of New Mexico until after World War II had ended. Oppenheimer and Groves never intended to create a community at the site of the secret Manhattan Project facility. Neither did they fully comprehend the ways in which their work would transform New Mexico and the world.

Prior to the development of the lab, Pajarito Plateau was home to a boys’ ranch school. It was an isolated, pristine space where young men lived and learned in wilderness conditions. During his career at Berkeley, Oppenheimer spent summers at a cabin in the area. He realized that the locale not far from the Jemez Mountains provided an abundance of open space in a place where most people would never expect to find an atomic weapons laboratory. He also loved the northern New Mexico wilderness, and welcomed the opportunity to carry out the project there.

T. Harmon Parkhurst (photographer). Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 001318.

Site Y, as the laboratory was first designated, was also ideal due to its proximity to uranium mines in western New Mexico, near Grants and Gallup. The open deserts near Alamogordo in the southern part of the state later provided an ideal site for a test detonation of the first atomic bomb. As later analysts have commented, New Mexico is something of a “Nukes-R-Us.” If New Mexico were to secede from the nation today, it would be the third largest nuclear power on earth.13

Courtesy of Los Alamos National Laboratory

Today, the nuclear industry is the economic backbone of northern New Mexico. About thirteen percent of the residents of nearby communities are directly employed at Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) and another thirty percent are indirectly employed at the labs through contractors with ties to the facility. As geographer Jake Kosek has pointed out, “much of the nuclear cycle takes place on indigenous lands: from uranium mining on Navajo lands; the design and building on Pueblo lands; testing in the indigenous outback of Australia and the South Pacific and here in the United States on Shoshone-Paiute land; and the national nuclear waste dump, also on Shoshone lands.”14

Initially, Oppenheimer and Groves decided to move between thirty and forty scientists and their families to Site Y to create a unified, top-secret effort. The facility that they pioneered later became known as the Special Weapons Laboratory. The scope of the Manhattan Project far exceeded initial expectations, however. By the end of the war, there were over 6,500 scientists and their families living at the site.

Los Alamos proved to be the ideal location for the project, and it hastened progress on atomic technology, just as Oppenheimer had hoped. The site was extremely remote; a single dirt road led to the entry gate, facilitating surveillance of everyone and everything that came and went. Those assigned to work at the laboratory reported to an office in Santa Fe where they presented their credentials and were then transported by bus to Site Y. All mail was also delivered to Santa Fe, and the site was alternatively known by its post office box number, P.O. Box 1663. The laboratory was one of the most tightly shielded secrets of World War II.

Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory (photographer). Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 030187

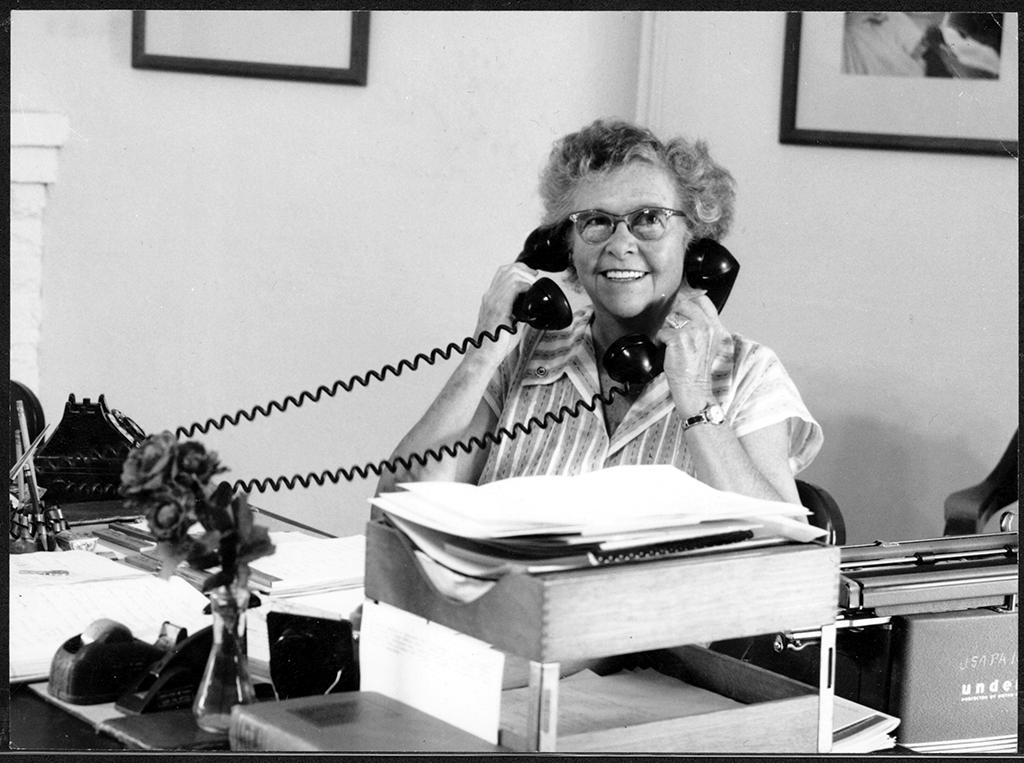

Dorothy McKibbin led the office at 109 East Palace Avenue in Santa Fe where new members of the Manhattan Project first reported. A widow in her mid-forties, McKibbin was one of the “unsung heroines of the Manhattan Project.”15 She ushered every new recruit to the project onto the buses that took them to Site Y. She also had to discreetly turn away those who arrived at her office looking for information about the secret activities that were taking place on the Pajarito Plateau. McKibbin was the face of a project that, to the public, did not exist.

Among those who reported to the site were European scientists included in the self-imposed exile—the Brain Drain. Not only physicists, but also engineers, psychologists, sociologists, and other public intellectuals fled Europe for Great Britain and the United States. It is estimated that they numbered nearly 25,000. European physicists joined their American counterparts at Site Y in support of the Manhattan Project. Their ages ranged from 19 to 60 years old, and many remained at Los Alamos after the war when the burgeoning Cold War ensured the continuation of nuclear research and development.

Notable among those at Site Y were Niels Bohr, who escaped from Nazi-occupied Denmark; Enrico Fermi, who fled fascist Italy; Edward Teller, originally from Hungary; Victor Weisskopf, an Austrian-born Jewish physicist; and Hans Bethe, a German Nobel Prize winner. Along with the well-known scientists were hundreds of others, called the Special Engineer Detachment (SED). Los Alamos was arguably the most stimulating intellectual community in the world during the war.

Not only did the physicists and engineers focus on atomic development. Many of them followed other intellectual pursuits as well. Oppenheimer, for example, spoke nine different languages. He had learned to read Sanskrit because of his interest in Hinduism and his desire to read the Vedic texts in their original language. Nearly all of the scientists took an interest in local history and cultures. Fermi, Bohr, and Oppenheimer toured nearby San Ildefonso Pueblo and sites at Bandelier National Monument.

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

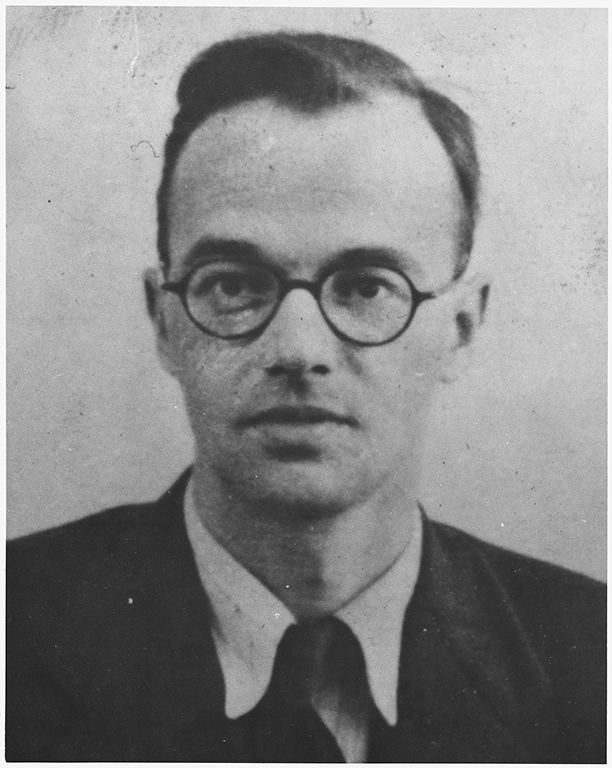

Although General Groves had been hesitant to relocate the project to New Mexico due to security concerns, Site Y remained secret until the end of the war. As noted at the beginning of this chapter, even the physicists’ wives did not know what their husbands were actually working on. Following the war’s conclusion, British-German scientist Klaus Fuchs passed information about the Manhattan Project to Soviet informants—reportedly at a pizza parlor in Santa Fe. Otherwise, a veil of secrecy shrouded Los Alamos.

Local construction companies from Santa Fe, as well as nuevomexicanos from small towns in Rio Arriba County, hired on to build the facility, so New Mexicans knew that the federal government was active on the Pajarito Plateau. They did not know what the facility was for, however. In that context, a series of rumors spread throughout northern New Mexico. Some believed that the facility was a poison gas factory, others that it was the manufacturing site of space ships, and still others that it was a hospital for pregnant members of the Women’s Army Corps (WAC). Interestingly, Oppenheimer spread a counter-rumor that the facility was the development site of a semi-electric rocket.