The History of New Mexico

Collapse

Expand

-

Chapter 10: Americanizing & Modernizing Ethnic Identities

- Americanizing & Modernizing Ethnic Identities

- "Apache Wars" & The Border

- Creating The Land of Enchantment

- Spanish-American Ethnic Identity

- References & Further Reading

Along with forging new connections with the burgeoning national economy and creating a new tourist image of New Mexico, the railroad gave rise to new towns and caused existing ones to split in two. Raton, Gallup, Springer, and Deming were among the new settlements inspired by the railroad. All were inhabited by predominantly white populations. By comparison, established towns like Las Vegas and Albuquerque maintained their majority hispano populations.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

The railroad drastically altered the existing demographic and urban landscape. Albuquerque, for example, split in two. New Town, the present-day downtown area, was constructed around the rail depot, primarily by whites. Hispano residents maintained Old Town a few miles to the west of the depot. Despite claims by some territorial officials, most notably Governor L. Bradford Prince, that New Mexico was the site of tri-cultural harmony (cooperation between hispanos, Pueblos, and whites), such characterizations glossed over the tension, conflict, and segregation that also accompanied the developments of the late-nineteenth century.

In the midst of such changes, as well as protracted efforts to Americanize New Mexico’s people, many nuevomexicanos began to describe themselves as “Spanish American” when they spoke English. When speaking Spanish, they often used the term “Hispano-americano.” By doing so, they attempted to push back against programs that targeted the Spanish language, and also to accommodate the prevailing power structures in the territory that promoted Americanization and modernization. As historian John Nieto-Phillips argues, the new mode of self-identification was a strategic decision that emphasized nuevomexicanos Spanish ethnicity and American nationality in order to distance them from “the ‘Mexican’ label that Anglo-Americans had used to disparage them.”19

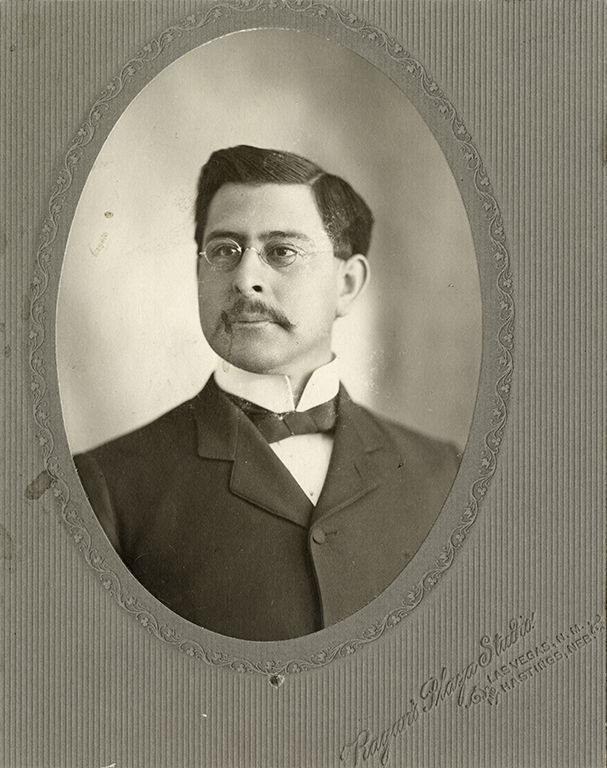

Influential ricos, such as Eusebio Chacón, were the first proponents of the shift to identification as Spanish-American rather than nuevomexicano, mexicano, or Mexican. Chacón was born in Peñasco in 1870. He attended the Jesuit College in Las Vegas, New Mexico, before going on to earn a law degree from Notre Dame University in 1889. Soon after, he moved to his parents’ new hometown of Trinidad, Colorado, where he edited the Spanish-language El Progreso newspaper. His ideas influenced hispano communities from Las Vegas northward into southern Colorado.

Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 050356

Chacón was known for his eloquent and fiery speeches in defense of nuevomexicano society and identity. In order to emphasize that his people had a long heritage of education and civilization, he disassociated from his family’s Mexican past in favor of their distant Spanish ancestors. In a 1901 speech delivered in Spanish in Las Vegas, for example, Chacón asserted, “I am Spanish American as are those who hear me. No other blood circulates through my veins but that which was brought by Don Juan de Oñate and by the illustrious ancestors of my name.”20

As we have seen, New Mexico was a place of ethnic and cultural conflict and accommodation since its earliest history, not an “island of pure Spanishness” as Stanford folklorist and native New Mexican Aurelio Espinosa asserted. The pressing question, then, becomes why nuevomexicanos created and adopted a means of identifying themselves that erased other elements of their heritage.

Although a study of genealogical records fails to support Chacón’s claims, the construction of Spanish American identity was a significant element of nuevomexicano efforts to portray themselves as worthy of equal treatment within the United States. Spanish American identity was also a major component of the statehood struggle. Emphasis on their Spanish patrimony helped New Mexico’s hispanos to claim a clear connection to a white, European heritage. The nineteenth-century construction of Spanish American identity has a persistent legacy that continues within many northern New Mexico communities to this day.

A heated exchange in the New York Times in 1882 between a resident of Trinidad and L. Bradford Prince, then Chief Justice of the Territorial Supreme Court, illustrates the type of acrimony that many white Americans held toward New Mexico’s people. The anonymous resident of Trinidad wrote a letter to the editor under the headline “Greasers as Citizens,” in which he argued that New Mexico should never become a state because “about two-thirds the population of the Territory is the mongrel breed known as Mexicans—a mixture of the Apache, negro, Navajo, white horse-thief, Pueblo Indian, and old-time frontiersman with the original Mexican stock.” Prince responded that no African American heritage existed in the territory, and that Pueblo and Spanish intermixture never took place because the two “races . . . are as separate in such respects as if a Chinese wall ran between.”

Prince emphasized both the Spanish heritage of New Mexico’s people as well as their loyalty to the United States—something that always seemed to be in question. He reminded the readers of the New York Times that nuevomexicanos had volunteered to serve the Union during the Civil War and that they had accepted nearly 20,000 white newcomers to their territory in the few years that Prince had served there. To bolster his argument that New Mexicans were civilized, loyal, educated, law-abiding, and hospitable, Prince presented them as having a white, European heritage by characterizing them as “the worthy sons of the Conquistadores.”21

As people of white, European descent, Prince also asserted their right to speak and write in the Spanish language. Some other observers referred to New Mexicans’ “refusal” to speak English as an act of treason. Prince instead touted the regular publication of over forty newspapers in the territory, “part are printed in English, part in Spanish, and part in both languages.”22 Indeed, New Mexico’s print history dated back to Father Antonio José Martínez who promoted various forms of publishing following the arrival of the first printing press via the Santa Fe Trail in 1834. From Prince’s perspective, the preponderance of newspapers illustrated New Mexicans’ preparedness to govern themselves and to join the union as a full-fledged state. Prince’s arguments, while pro-nuevomexicano, misrepresented the level of ethnic intermixture that characterized the territory. He also incorrectly denied the place of African Americans in New Mexico.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

Eusebio Chacón’s generation was the first to come of age in the crucible of competing interests that simultaneously forced nuevomexicanos to accommodate to white Americans’ expectations of them and pushed them to create innovative means of preserving their unique heritage, language, and history. Figures like Jesús María Hilario Alarid, Eleuterio Baca, and Enrique H. Salazar, among many others, edited Spanish-language and bilingual newspapers in the territory. Many other nuevomexicanos wrote down oral traditions that had been passed down in their families and submitted them for publication in the periodicals.

New Mexico’s strong Spanish-language print culture served as a vehicle to preserve nuevomexicano history and perspectives, while simultaneously emphasizing New Mexicans’ Spanish American heritage. Others also picked up the line of reasoning that legitimized New Mexico as a Spanish American territory. In the early twentieth century, scholars like Aurelio Espinoza and historian Herbert Eugene Bolton asserted the value of understanding the Spanish past in New Mexico and the Southwest. Literary figures in northern New Mexico, including José de Cena, Cleofas Jaramillo, Adelina “Nina” Otero-Warren, and Fabiola Cabeza de Baca-Gilbert published novels, fliers, and cookbooks to preserve nuevomexicanos’ Spanish language, folklore, genealogy, clothing, music, and food.

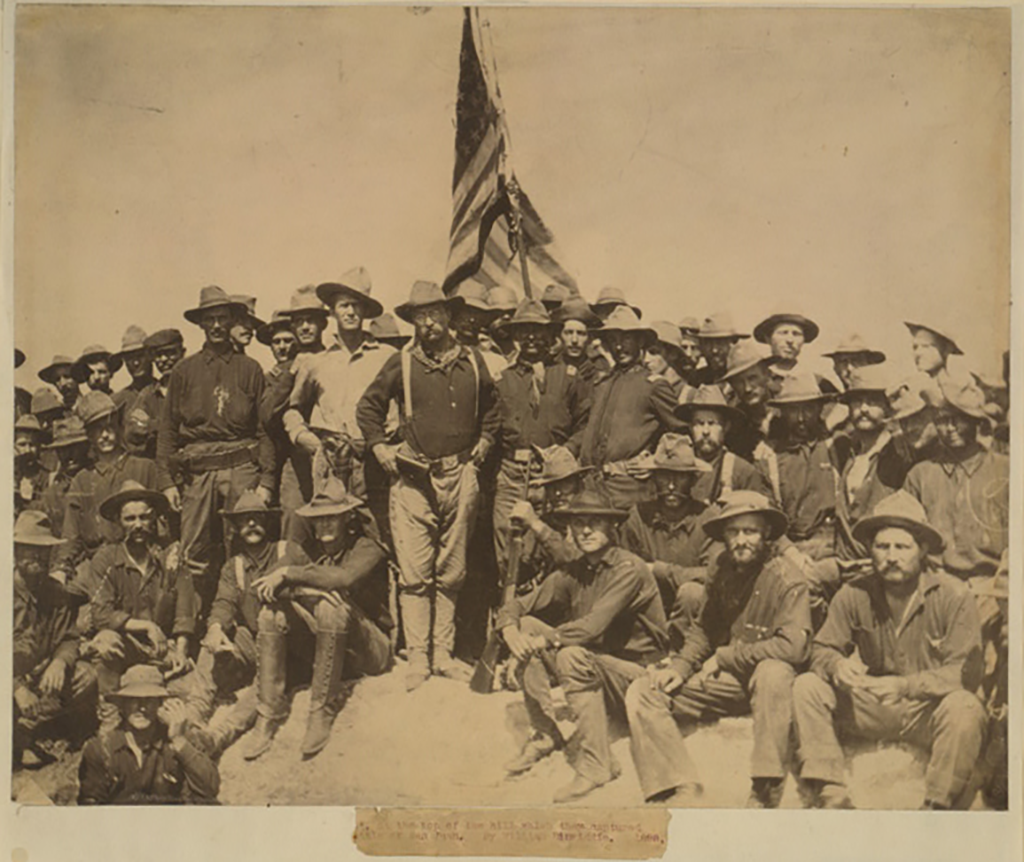

During the Spanish-Cuban-American War of 1895-1898 the claim to Spanish American identity became more complicated because Spain was an enemy of the United States. To negotiate that new reality, New Mexicans emphasized the “American” element of their chosen identity by volunteering in large numbers for service in the conflict. About 350 men served with Theodore Roosevelt’s famed Rough Riders in Cuba, and nearly 400 others in other regiments.

Courtesy of Donald Deesen Collection, Southwest Center for Research, University Libraries, University of New Mexico

Maximiliano Luna and George Washington Armijo were among the most decorated and celebrated New Mexicans to serve in the war. Luna came from a prominent Rio Abajo family and he had served as sheriff of Valencia County prior to his service in the war. He demanded to fight on the front lines of the conflict as a “man of pure Spanish blood” in order to show not only his individual dedication and loyalty to the United States, but also that of all nuevomexicanos.23 Luna served honorably with the Rough Riders in Cuba, and was then assigned to the Philippine theater where he was killed in combat.

Armijo’s given names emphasized his parents’ desire to showcase their dedication to the United States. Unlike Luna, he survived the war and built a career in the military. Both of these men and many of the hundreds of others who fought in the Spanish-Cuban-American War hoped that their efforts would hasten the statehood process. Indeed, some saw Luna as a martyr for the cause of statehood. Of course, many New Mexicans understood statehood as the signal that their full citizenship rights would finally be guaranteed.

The assertion of Spanish American ethnic identity countered the racial hierarchy that placed white Americans at the top. Rico New Mexicans asserted their place as leaders in the territory by asserting their Spanish American heritage, and they also presented an image of New Mexico’s history and peoples that challenged the racist notions of those opposed to statehood. In sum, Spanish American ethnic identity was an effort to create an ideal whose cultural roots were white and European, thus allowing New Mexicans to claim a heritage that they believed was on par with that of white Americans.

The reputed gains of Spanish American ethnic identity, however, came at a cost. Nieto-Phillips also reminds us that despite prominent nuevomexicanos’ adoption of their new identity, there is little evidence of how poorer nuevomexicanos reacted. Many, it appears, supported their patrones’ political ambitions and views, but few lower-status New Mexicans left records of their perceptions of claims to pure Spanish heritage.

By the first years of the twentieth century, Prince, Chacón, and others emphasized a concept that has since become known as the tri-cultural myth: the idea that people of Spanish, Anglo, and Pueblo descent lived in harmony in New Mexico.24 Such notions overemphasized cooperation and negated a history of conflict and resistance that accompanied efforts to Americanize and modernize New Mexicans’ sense of ethnic heritage. The myth also ignored the presence of African Americans, Asian Americans, and people of other ethnicities in New Mexico.

The conclusion of long years of war against Native Americans (including campaigns against the Navajos and various Apache bands) in 1886 signaled that the territory was safe for capitalist development. The Santa Fe Railroad and Fred Harvey Company rushed to monopolize the tourism industry in New Mexico, and, as they did, each corporation reinvented and reproduced New Mexican peoples and cultures. Within the context of Americanization and modernization, many nuevomexicanos constructed a Spanish American ethnic identity for themselves.

Despite the harmony suggested in the tri-cultural myth, other segments of New Mexican society employed militancy and violence to resist the changes wrought in the territory in the late nineteenth century. Among them were Las Gorras Blancas, or the White Caps. Additionally, many poor nuevomexicanos simply sought to eke out a living for themselves and their families within the burgeoning capitalist economy. Their methods of resistance and accommodation are the subject of the next chapter.