How Long Did New Mexico’s Slave Code Last?

The 1859 New Mexico slave code was perceived in the territory as nothing more than a political concession made to Southern legislators in exchange for their support for statehood. The slave code only remained on the books for only two years.

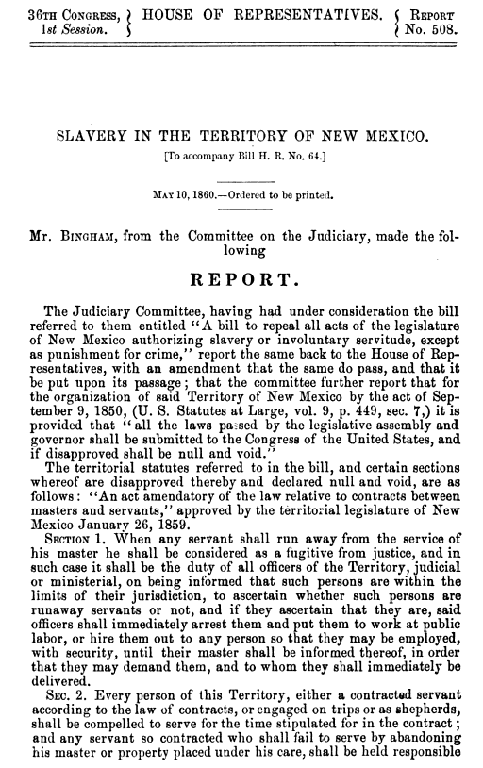

n 1859, the territorial legislature enacted a harsh slave code. One of the leading Republicans in the U.S. Congress, Representative John A. Bingham of Ohio, characterized the legislation as a statute that would have made even Caligula blush.1 On its face, the slave code presents a seeming historical paradox. Between 1848 and 1850, New Mexico’s bid for statehood set it up to become a free state. Sectional strife, however, led instead to the narrow passage of the Compromise of 1850—a measure that preserved the Union for what proved to be a fleeting moment and that denied New Mexico’s elevation to statehood.

New Mexico did not have a large population of black slaves. Very few American newcomers sought to expand the “peculiar institution” into the territory’s desert landscapes because they could not sustain plantation agriculture. The slave code was the product of political wrangling in Washington D.C. between Miguel A. Otero, Sr., the territorial delegate to Congress, and Southern legislators. Recognizing the political significance of statehood, several Democratic Congressmen, including Representative Ruben Davis of Mississippi, approached Otero with the promise of their support in exchange for the creation of a slave code in New Mexico.

Otero was himself a Democrat, as were several key territorial leaders appointed during the administration of James Buchanan. Governor Abraham Rencher, territorial secretary Alexander M. Jackson, U.S. marshal Charles P. Clever, and editor James L. Collins of the Santa Fe Gazette were among them. Although Republicans used their knowledge of conversations between Otero and Democratic legislators in Washington to argue that the slave code was not favored by the people of the territory and instead the product of backroom deals, Otero consistently denied such charges. He repeated the well-worn justification that the slave code “will tend to elevate our own class of free laborers.”2 His words echoed similar arguments made throughout the South in an effort to cast slavery as beneficial both socially and economically.

New Mexico’s socioeconomic system was quite a bit more complex than the dichotomy between Northern free labor and Southern slave labor that typically defined national political discourse. Many poor nuevomexicanos and Pueblos were subject to peonage, or forced labor required to pay off debts. Large landholders, predominantly the Rico class prior to 1848, provided items necessary to agricultural production, like seeds, tools, and livestock, that their impoverished countrymen and women could not afford. Typically, peons were rarely able to repay their debts fully and they labored on the lands of their patrón indefinitely.

“Peones were rarely able to repay their debts fully and they labored on the lands of their patrón indefinitely.”

As New Mexico was drawn into the national conflict over slavery, many in the Eastern United States conflated the idea of peonage with chattel slavery. From the perspective of Washington, D.C., the bid for statehood in the early territorial period became inextricably tied to the sectional strife that devolved into Civil War in 1861. Back in New Mexico, debate over the slave code was far more contentious and complex. The bill itself, solemnized in the territorial legislature in February 1859, was titled, “An Act for the Protection of Property in Slaves in this Territory.” Prominent territorial policy makers, including Donaciano Vigil (San Miguel County), Juan José Sánchez (Valencia County), and Albino Chacón (Taos County) supported the measure’s passage. They also separated its provisions from legislation dealing with escaped peon servants in the territory. The law only applied to black slaves brought to New Mexico from outside the territory. It specifically excluded indigenous slaves, still a major component of New Mexican society, although a later iteration of the law added a provision “for the protection of Indian property.”3

Despite the seemingly high level of support for the measure among New Mexico’s powerbrokers, a large section of the local population opposed the law. Led in the territorial legislature by Samuel B. Watrous (Mora County) and Speaker of the House Levi J. Keithly (San Miguel County), opponents of the measure attempted to repeal the law in December 1859. Repeal supporters viewed the slave code as the attempt of outside interests to impose their will on New Mexico. As one supporter of repeal noted, “The subject was never discussed, nor even mooted before the people, but was got up near the close of the session and hurried through, when the country did not dream of anything of the kind.”4

New Mexico territory became a major component of debates over slavery that raged in the U.S. Congress in early 1860. Anti-slavery Republicans introduced a measure to strike down the slave code. Due to New Mexico’s territorial status, Congress retained veto power over legislation crafted in Santa Fe. In the end, attempts to quash the law at both the national and territorial levels failed. Following the outbreak of Civil War with the conflict over Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, in April 1861, New Mexico’s territorial legislature overwhelmingly affirmed the territory’s loyalty to the Union. To illustrate their resolve, representatives in both chambers almost unanimously voted to repeal the slave code in December 1861.

The New Mexico slave code remained on the books for a short two years, and its passage did not create a new influx of African American slaves to the territory. Its story, however, highlights three major trends in the territorial history of New Mexico. First, the territory was much more tightly connected to the struggle between North and South than typically assumed. Second, the struggle for statehood depended on many distinct factors, foremost among them the whims of the U.S. Congress. Negative racial perceptions toward New Mexico’s people and (unfounded) misgivings about their ability to participate effectively in representative government were among the others. Finally, the creation and dissolution of the slave code illustrates the types of ethnic tensions that ran hot in the territory.

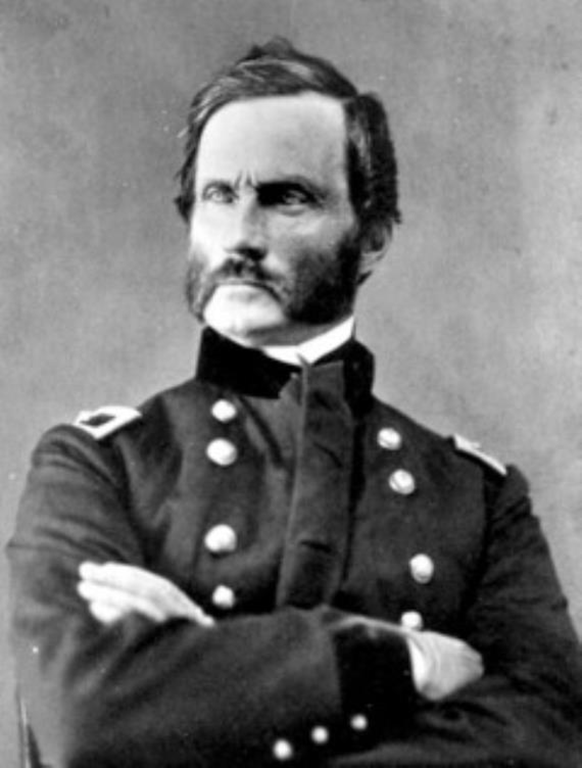

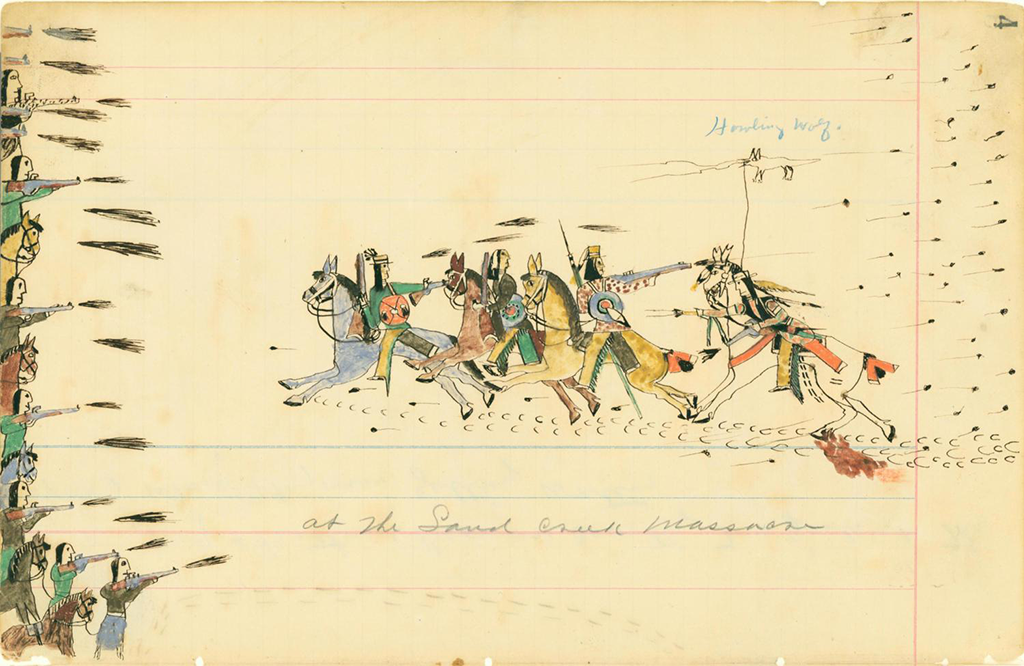

During the early territorial period, New Mexico was the site of intense battles between Union and Confederate forces. Union forces effectively repelled Confederate troops from the territory in the 1862 Battle of Glorieta Pass, and James H. Carleton, military commander of the department of New Mexico, turned his attention toward Native Americans. His desire to relocate Mescalero Apaches and Navajos to the doomed Bosque Redondo reservation was translated into horrific reality through the efforts of Christopher “Kit” Carson. The Treaty of 1868 ended the failed “Reconstruction experiment” at Bosque Redondo and returned the Navajo people to their homeland. Political corruption and lawlessness, evidenced in the Colfax and Lincoln County Wars a decade later, perpetuated the idea that New Mexico remained ill-prepared for statehood. From the perspective of Washington, D.C., the territory still lacked modernization and Americanization.