In the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, it seemed that disputes over land, resources, and the place of former Mexican citizens in the United States had been resolved. Such was not the case, however. Even the outwardly straightforward issue of surveying the new international border between the two nations presented a series of problems. In Texas and California, tejanos and californios were quickly outnumbered by Anglo American migrants and they lost much of their political and economic power.

Nuevomexicanos, on the other hand, continued to comprise the majority of New Mexico’s population well into the twentieth century. In order to prevent their full inclusion in national affairs, at least in part, Congress refused to approve New Mexico’s statehood for sixty-four years. Nuevomexicanos sought to maintain their unique cultural heritage and ties to friends and family members in Mexico despite continued legal schemes that robbed them of their rights as heirs of Spanish and Mexican land grants. They also fought a constant battle to defend their use of the Spanish language. Although some decided to accept the offer of the Mexican government to resettle south of the new border, most struggled to hold on to land and possessions that their families had claimed for hundreds of years.

Although their identification with the Mexican nation was gradual and transient, nuevomexicanos had not actively sought to exchange their ties to Mexico for U.S. citizenship—a status that gave them second class standing in their own homeland. As Chicano activists would remark much later, nuevomexicanos held that “the border crossed us.” Such sentiment has lasted to the present among Mexican-heritage peoples in

In 1849, however, the border crossed Mexican residents of several northern Chihuahua towns in a far more literal way. In order to understand the events that transpired when the Rio Grande (Rio Bravo del Norte) changed course in 1849, we need to also consider the Mexican government’s efforts to repatriate Mexican citizens in the ceded territories. During the treaty negotiations the question of whether or not the rights of citizens in the lost territories would be protected loomed large in Mexican officials’ minds. As President Manuel de la Peña y Peña remarked, “their future has been the gravest difficulty I have had in the negotiations; and . . . had it been possible, the territorial cession would have been extended with the condition that the Mexican populations be set free.”16

The preoccupation that Mexican people would not receive equal citizenship rights in the United States dated to the early 1800s. In 1822 Mexico’s Ambassador to the United States reported that Americans openly considered themselves racially superior to Mexican people. Coupled with the well-known American penchant for expansion, this news stoked fears of an eventual invasion. An 1839 story in La Luna, a Chihuahua newspaper, warned that if such an invasion occurred, Mexicans would be “sold as beasts” because “their color was not as white as that of their conquerors.”17 Indeed, Mexican commentators on racial attitudes in the United States justifiably feared that their compatriots would be counted with African Americans in such an event, and possibly subjected to slavery.

During New Mexico’s tenure as part of the Mexican Republic, nuevomexicanos forged a sense of Mexican identity based on symbols and rituals. As was the case in all emergent nation-states, flags, coins, seals, medals, and public performances allowed disparate peoples far from national seats of power to adopt a shared sense of belonging and purpose. This process began in Santa Fe when the Mexican flag was raised in the plaza at the first independence celebrations. Additionally, rituals, such as the requirement that land grantees chant verbatim the words “Long live the president and the Mexican nation” in order to take possession of their grants, constructed a sense of Mexican identity.18

In 1848, New Mexico was the most populous of the lost provinces. Non-indigenous inhabitants numbered nearly 60,000. Not long after ratification of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the Congress in Mexico City approved a measure to help the residents of its former territories relocate to Mexico. The law passed on June 14, 1848, set aside 200,000 pesos (taken from the U.S. indemnity payment) to help “diminish the disgrace” of Mexican nationals living in the ceded territories by offering them a means of repatriation. Although the term repatriation is defined as the process of returning displaced peoples to their home countries, historians have also applied it to the case of the people crossed by the new international boundary. In their case, however, they had to leave behind their homes in order to rejoin what many considered to be their nation of origin.

The Mexican legislature appointed three commissioners, one for each of the lost territories, to act as repatriation agents. The New Mexico commission was the anchor for the others because it was the most populous of the ceded regions. Father Ramón Ortiz, parish priest at El Paso del Norte (today’s Ciudad Juárez) was the official representative for New Mexico. As outlined in the legislation, heads of household that emigrated to Mexico were to receive twenty-five pesos for each family member over the age of fourteen and twelve pesos for each minor. Such payments were intended to defray the costs of relocation.

Additionally, state governments, particularly along the newly established border, donated lands upon which the repatriates could settle. Governor Angel Trías of Chihuahua welcomed the opportunity to provide lands for the resettlement of nuevomexicanos in the northern part of his state. Like other northern governors, he believed that the increased population would guard against filibusters and the incursions of indios bárbaros alike. In January of 1849, he presented a plan to hasten repatriation efforts that the state legislature quickly approved. A land survey established a colony named Guadalupe on the south bank of the Rio Grande, to the south of El Paso del Norte.

With the support of Governor Trías, Father Ortiz began his journey northward toward Santa Fe. Delayed by harsh winter snowstorms, Ortiz reached Santa Fe in March of 1849 to share information about the Mexican repatriation program and recruit potential emigrants. Despite the weather, Ortiz was quite optimistic. While he waited out the winter in his parish, he received twenty petitions for resettlement from nuevomexicanos living near El Paso del Norte. The unexpected success led him to estimate that between 2,000 and 4,000 families would relocate to Chihuahua.

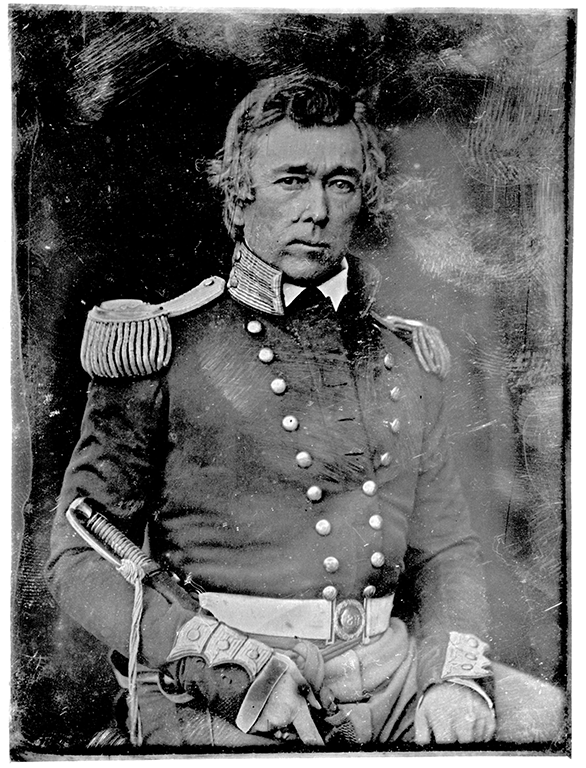

Accompanied by associate Manuel Armendáriz, Ortiz met with territorial governor John M. Washington and territorial secretary (lieutenant governor) Donaciano Vigil when he reached Santa Fe. The territorial officials welcomed Ortiz and Armendáriz, promising to aid their efforts in whatever way possible, even offering transportation to facilitate the commissioners’ travels in the territory. Municipal officials were less enthusiastic about Ortiz’s presence, however, fearing that the offer of resettlement would intensify political and social conflicts that had abated since the Taos Revolt, but that had not completely disappeared.

Only a couple of weeks after that initial meeting, Ortiz found that 900 of the approximately 1,000 families that resided at San Miguel del Vado, about 60 miles east of Santa Fe, wished to repatriate. In his account of his work, Ortiz wrote that he had barely arrived in the town when its residents approached him to express their desire to relocate to Mexico. He recalled, “Although they knew they would lose all their property, notwithstanding the guarantees of the peace treaty, they preferred to lose all rather than belong to a government in which they had fewer guarantees and were treated with more disregard than the African race.”21

“Ortiz found that 900 of the approximately 1,000 families that resided at San Miguel del Vado, about 60 miles east of Santa Fe, wished to repatriate.”

Energized by the encounter, Ortiz then traveled toward Taos. While at Pojoaque Pueblo, he received an order from Donaciano Vigil that he immediately abandon his registration campaign. Vigil claimed that Ortiz had created grave disturbances among the local population. Disheartened, the priest returned to Santa Fe where he learned that local authorities had also prohibited him from registering families for repatriation. Over the course of the next few days, Vigil vacillated. After a meeting with Ortiz he rescinded the order to cease and desist. Not long thereafter he once again demanded that the priest halt his activities. In the interim, Ortiz registered two hundred Santa Fe families for repatriation.

U.S. officials, including Vigil, at the territorial and municipal levels ultimately opposed the repatriation campaign because of its potential to depopulate the New Mexico territory and because they feared that it could further polarize its already divided inhabitants. At the time statehood seemed an attainable goal, but if the population diminished at all New Mexico would no longer meet the minimum requirements for joining the Union. According to Vigil’s final order, Ortiz could not register any other individuals or families until territorial officials obtained the signatures of those who wished to maintain their Mexican citizenship. By taking that step, Vigil tied the repatriation project to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo’s provision that residents of the ceded territories be allowed one year to declare their citizenship intentions. Despite the inclusion of such a provision in the treaty, no system for the declaration of citizenship existed because the territorial government repeatedly blocked the creation of such a mechanism.

Municipal officials employed the language of nationalism to discourage nuevomexicano emigration. In May 1849, the territory’s official periodical, the Santa Fe Republican, cast Mexican authorities in a negative light with the assertion that the repatriation program was not in the potential repatriates’ best interests. The editorial, written in Spanish, argued that meager funding was evidence that the Mexican government was not truly invested in the effort. In return for leaving behind all of their property and most of their possessions, the migrants would face the raids of nomadic peoples in the New Mexico-Chihuahua borderlands. Based on such information, the Republican admonished readers that the Mexican authorities “clearly do not wish you to return to the ranks of their family.”22 Most nuevomexicanos recognized that they were to be relegated to second-class citizenship if they remained in their homes. The Republican and other repatriation opponents claimed that they would face the same fate if they relocated.

In reality, the Mexican government was never able to adequately fund the program or provide for the needs of the repatriates. Historians had long interpreted the Mexican government’s efforts as benevolent and protective of its lost citizens. Based on archival research in little-consulted municipal archives throughout Chihuahua and New Mexico, historian José Angel Hernández has argued instead that the Mexican state was “an institution distantly attending to repatriation as if it were a colonial afterthought.”23 Despite the promise of subsidies, most who emigrated to Mexico did so voluntarily, on their own dime. This is not to say that the administrators involved were devoid of good intentions, but the divisions within Mexico following the U.S.-Mexico War meant that material support for repatriation was inadequate and rare.

Father Ortiz tenaciously worked to salvage the situation. Prohibited from registering potential repatriates in New Mexico, he returned to Chihuahua in an attempt to shore up resources. He hoped to secure from the state legislature and municipal governments funds, lands, seeds, tools, and materials to support resettlement, despite seemingly insurmountable obstacles. According to his best estimates, nearly 80,000 people were willing to relocate to Chihuahua. Based on that number, at least $1.6 million, 145,000 bushels of corn, and 39,000 bushels of beans were needed to support the repatriates as they worked to bring their own lands under cultivation.

In an effort to overcome the conflict with New Mexican authorities, Ortiz sent Manuel Armendáriz to Mexico City as his liaison. Armendáriz worked to persuade Mexican authorities to provide additional aid for repatriation, including diplomatic support in Washington, D.C. The Mexican ambassador to the United States attempted to intervene with the complaint that U.S. officials had mistreated Ortiz, an official emissary from Mexico. In response, U.S. officials claimed that they had no way of knowing if Ortiz acted in official capacity since no provision for repatriation was made in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. To address the conflict, the Mexican government appointed Armendáriz as Consul to New Mexico.

In the midst of such political wrangling, in late 1849 the Rio Grande shifted its course to a new channel. The event was no surprise to locals. The river typically changed course depending on seasonal snowpack and usage patterns. Indeed, the name used in Mexico and Latin America, Rio Bravo del Norte (Bravo meaning ferocious, bad-tempered, or stubborn), reflects this reality. The negotiations for the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which had drawn the international boundary, occurred in central Mexico among officials without such local knowledge, and based on the inaccurate, although current, Disturnell map.

Based on the treaty, which used the Rio Grande as the border between the two nations, once the river shifted the Chihuahua towns of Socorro, Isleta, and San Elizario were technically on the American side of the boundary. American military forces hastily occupied the towns. Residents decided to leave their homes for the recently established civil colony of Guadalupe rather than run the risk of another armed conflict. Once in Guadalupe, they petitioned for aid under the auspices of the repatriation legislation of 1848. Little by little, resources in Chihuahua were made available for them.

“Due to the caprice of nature, its residents found themselves in the United States despite their allegiance to Mexico.”

The town of Doña Ana was also impacted by the shifting river. Due to the caprice of nature, its residents found themselves in the United States despite their allegiance to Mexico. Following General Kearny’s occupation of New Mexico in 1846, Colonel Alexander Doniphan led troops southward to pacify residents of New Mexico beyond the northern Rio Grande corridor. As a result, Doña Ana’s people felt the pressure of colonization for nearly three years before the river shifted channels. The alteration in natural geography provided them the needed catalyst to action.

In early 1850, in part due to the movement of the river and in part due to the occupation of Doña Ana by Doniphan’s troops, those who wished to retain Mexican citizenship—about 60 families led by Rafael Ruelas—relocated voluntarily to a site that was later recognized as the civil colony of La Mesilla. Their numbers gradually increased due to migrations of families from other areas in New Mexico. Scholars have argued that the claim of 2,000 residents by the end of 1850 was likely exaggerated, yet the civil colony of La Mesilla grew quickly under the oversight of Father Ortiz. The reason for the argument against that figure is one American observer’s report that La Mesilla was home to between 600 and 700 people as of March 1851. At about that time, a binational border commission passed through La Mesilla.

River Changes Course

WITH Brandon morgan

Boundary surveyors from both nations met in El Paso del Norte in 1850 and learned that the border drawn by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, based on the Disturnell map, did not correspond to physical geography. Accordingly, these representatives of international diplomacy were required to make compromises based on what they found on the ground. On the American side, John Russell Bartlett and William Emory helped to negotiate the new boundary and Pedro García Conde represented Mexican interests. Because the Disturnell map suggested that El Paso del Norte was located near the actual location of present-day Roswell, New Mexico, the binational commission was forced to draw the international border as its members moved from El Paso del Norte toward the west.

The border commission’s eventual agreement seemed in many ways to favor Mexico. It is no surprise, then, that the negotiations were never approved by the U.S. Congress. Subsequent disputes, such as that over the Chamizal district in El Paso, also underscore the contentious nature of the agreements. Disagreement characterized relations between inhabitants of the new civil colonies as well. Most of the first residents of Guadalupe, for example, came from the towns of Socorro, Isleta, and San Elizario. Because they had relocated when the river first changed course, they occupied the best lands for their own use. By April of 1850, however, about six hundred families from various sites in New Mexico had joined them. The newcomers felt slighted because they were unable to gain access to lands and resources already claimed by the earlier settlers.

Abundant harvests in 1851 and 1852 helped to alleviate the tension in Guadalupe, but deeper concerns plagued the civil colony of La Mesilla. Upon learning that the border commission had officially placed the colony in Chihuahua, its residents held a fiesta in the town square. Despite Father Ortiz’s best efforts to organize the migrants from places including Albuquerque, Belen, Tomé, and Socorro, and even with the creation of a new colony—Santo Tomás de Yturbide—on the southern end of La Mesilla, local resources were not enough to support the settlements. The impulse for repatriation was much stronger than Mexican legislators ever hoped. Accordingly, insufficient resources for the large numbers of migrants characterized the early period of repatriation after the U.S.-Mexico War.

When James Gadsden finalized the Treaty of La Mesilla in 1853, La Mesilla was declared legally and officially within the territorial limits of the United States. Although Gadsden had hoped to acquire far more territory, including, perhaps, Chihuahua, Sonora, Nuevo León, and Coahuila, the treaty limited the newest territorial gain to a 29,670 square mile parcel, known as the La Mesilla strip. As fate had it, none other than Antonio López de Santa Ana was the Mexican president who negotiated the purchase. To this day, he is vilified as the person that twice lost large swaths of Mexican territory. Indeed, the inhabitants of La Mesilla have been called “los vendidos de Santa Ana” (those who Santa Ana sold out).

Although we might think that mesilleros would have been determined to reassert their Mexican citizenship in 1853, such was not the case. The territorial governor of New Mexico, James S. Calhoun, tried to force claims to La Mesilla and other areas held by Chihuahua in early 1851 when he rejected the boundary commission’s settlement. Eventually, those that had migrated to La Mesilla were willing to recognize the New Mexico, and by extension United States’, claim when the Mexican government proved unable and unwilling to make good on the promises of the 1849 repatriation legislation. They realized that they were considered pawns in both nations’ territorial ambitions, and, by 1853, they decided to throw in their lot with the United States.

As historian José Angel Hernández has suggested, “Repatriation, therefore, became a vehicle that trapped Nuevo Mexicanos within seesawing efforts to populate national peripheries.”24 Such was the reality for “los vendidos de Santa Anna.” In 1853 they resigned to see what their place in the United States might be—despite earlier warnings that they would be afforded as few rights as slaves in the American South. The Mexican government’s failings, both at the national level and at the state level (Ortiz began to work through the auspices of the Chihuahua government after New Mexico territorial officials denied him access to local populations), meant that nuevomexicanos who wished to assert their Mexican citizenship had to do so without any outside support whatsoever. Despite the promise of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, they sacrificed their own properties and resources to assert Mexican citizenship—if they chose to do so.

The case of Pueblo peoples and nomadic indigenous groups, such as Apaches, Navajos, Utes, and Comanches, was even less fortunate. The citizenship rights afforded them by the Mexican Republic disappeared under U.S. jurisdiction. Greed and desire for resources ostensibly unutilized by indigenous peoples provided a justification for the continuance of Manifest Destiny even after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo had been signed and solemnized. Such was the basis for the period of “Indian Wars” that characterized much of New Mexico’s early territorial period, to which we will turn in the next chapter.