The History of New Mexico

Collapse

Expand

-

Chapter 13: The Great Depression & The New Deal

- The Great Depression & The New Deal

- Artist Colonies & Rural Reformers

- Depression Comes to New Mexico

- Dennis Chávez & The Hispanic New Deal

- Indian New Deal & Navajos

- References & Further Reading

In late-1937 Procopio Carabajo, a forty-six-year-old father of eight children who lived in Bernalillo, learned that the Works Progress Administration (WPA) would no longer allow him to work on federal projects geared toward alleviating the economic stress of the Great Depression. WPA administrators terminated him from the relief rolls due to his status as an “alien,” illegally present in the United States.

As Carabajo reported to the Albuquerque Journal, he had no idea that he was not recognized as a legal resident of New Mexico. Originally from Chihuahua, he crossed the border with his father in 1900 when he was nine years old. At that time the Border Patrol did not exist and authorities lightly regulated travel across the international boundary. Customs officials were primarily concerned with the international movement of cattle and goods, not people—with the exception of Asians who had been denied access to the United States under the Exclusion Act of 1882.

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

Beginning in 1912, Carabajo actively participated in electoral politics by voting. He also married and started a family. All of his eight children had been born in the United States and enjoyed U.S. citizenship. His oldest son, Robert, had enrolled with the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) in New Mexico. His youngest son was only four months old when Procopio learned the news that he would no longer be eligible for New Deal relief programs. Without the aid of the WPA, it would be very difficult for a man like Carabajo to find work at all.

According to WPA administrators interviewed by the Albuquerque Journal, a new federal law passed in June of 1937 required them to ascertain the citizenship status of all who worked on New Deal programs. Pete Rose, the WPA Employment Manager for New Mexico, reported that he had no idea how many non-citizens were currently on the bureau’s rolls because applicants had not been required to identify themselves by citizenship status prior to 1937. Carabajo and another man not identified by name in the report learned of their denial on the basis of non-citizenship when they reported to the County Clerk’s Office to re-register for benefits.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

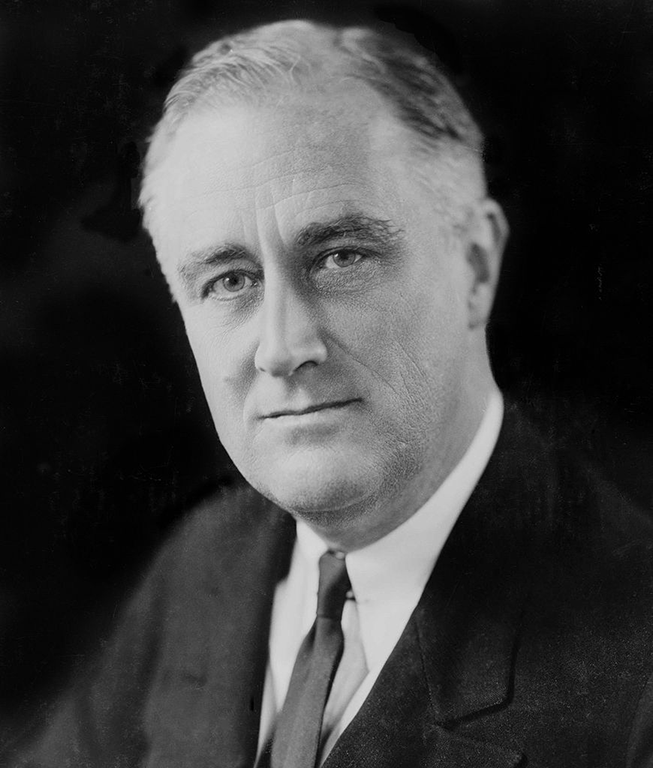

Carabajo’s case illustrates the unforeseen issues created by federal initiatives to “clean up” New Deal relief rolls in the late 1930s. Even President Franklin D. Roosevelt, remembered for creating the Welfare State in the United States, had reservations about deficit spending to support his New Deal economic recovery programs. When he urged Congress to pull back from such spending in 1937, the country entered a new recession, dubbed the “Roosevelt Recession” by contemporary observers and historians alike.

Agencies like the WPA sought to pare down their spending through a purge of non-citizens from federal programs. The focus on people called “illegal aliens” in the common speech of the time could be traced back to a 1933 Department of Labor effort to “voluntarily repatriate” Mexican nationals to their country of origin as a means of freeing up relief funds for white American citizens. Such repatriation programs were disingenuous at best, targeting all people of Mexican heritage, whether U.S. citizens or not, through a campaign based on fear. Deportation raids, the requirement that all Mexican-heritage people carry identification papers at all times, and concentrated radio campaigns instilled fear amongst the Mexican American populace. The result was the forced relocation to Mexico of thousands of people from places ranging from Gary, Indiana, to Los Angeles, California.

In New Mexico, the general atmosphere that inspired the repatriation campaigns also impacted nuevomexicanos who once again found that the legal promise of U.S. citizenship held little meaning in daily life. The cases of Carabajo and others like him also illustrate the continued arrival of new immigrants to New Mexico, despite the fact that the vast majority of Mexican-heritage people in the state were descended from those who lived in the area at the time of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

Courtesy of Herald-Examiner Collection, Los Angeles Public Library

According to Pete Rose, Carabajo and any other Mexican-heritage people in New Mexico illegally could pay a fee of $20 to register as residents. Although Procopio Carabajo never again appears in the historical record, we can assume that if he was unable to pay the fee, his son’s participation with the CCC would have been the family’s economic support. Others in similar situations, however, were not so lucky.

Just a few days after reporting on Carabajo’s situation, on November 28, 1937, the Albuquerque Journal ran a story that outlined the burden placed on women due to the WPA focus on eliminating undocumented people from its rolls. In addressing women’s status, WPA administrators looked to a 1922 law that addressed the citizenship of those who married “aliens.” Under that law, any woman who married a non-citizen prior to 1922 lost her citizenship status and was classified as an “alien” along with her husband. Men who married non-citizen women were not subject to the loss of their U.S. citizenship.

The WPA used the same standard to decide which women qualified for participation in its programs. According to an article in the Albuquerque Journal, women who married non-citizens prior to 1922 lost their citizenship by virtue of their marriage. The paper’s editors made the tongue-in-cheek assessment that the “only ‘sensible’ thing for a woman” in such circumstances to do was to get a divorce. In making such an analysis, the Albuquerque Journal cast the WPA measures as unjust.

Labor struggles also became a vehicle for political debate in New Mexico during the Great Depression, often at the expense of laborers. As reported in the July 18, 1936, edition of The Nation, New Deal liberals and others used racism to root out those who attempted to organize unions in New Mexico and the Southwest. A man named Jesús Pallares was deported for his efforts to unionize laborers in the coal mines of Madrid, New Mexico.

According to a report in The Nation, Pallares was “a skilled miner and an accomplished musician.”1 Like Carabajo, he arrived in New Mexico from Chihuahua during an era in which border enforcement focused on customs concerns rather than the migration of certain categories of people. Unlike Carabajo, he worked as a miner following his participation in the Mexican Revolution. He worked first in a mine in Dawson, and then in Gallup, New Mexico. During his tenure with the Gallup-American Coal Company, a subsidiary of Kennecott Copper, he attempted to organize his fellow workers for better wages and conditions. As a result, company officials fired him.

Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 089521.

Struggling to support himself, his wife, and their four children, he finally found employment in the Madrid coal mines after many months without an income. As was the case in many mining towns throughout the American West, Madrid was a company town. Despite the guaranteed right to collective bargaining, included in provisions of Section 7-a of the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA), the union in Madrid catered to the owners’ interests at the expense of the workers.

A veteran of unionization due to his experiences in Gallup, Pallares took steps to create an alternate union that would represent the demands of laborers in Madrid. Organization there was much more difficult than had been the case in Gallup. Although the coal company created a union to nominally comply with Section 7-a, Pallares quickly learned the “union” was more concerned with the bosses’ issues than those of the workers.

Pallares’ efforts to create a meaningful workers’ union at Madrid led him to association with the Liga Obrera de Habla Española (Spanish-Speaking Workers’ League). The league was the most prominent promoter of working nuevomexicano and Mexican nationals’ rights in New Mexico. Officials labeled it an anarchist, or radical, organization in an attempt to strip it of legitimacy. Ultimately, Pallares’ tireless work to advocate for workers’ rights came to naught when he was deported in the summer of 1936.

The experiences of Carabajo, women married to “aliens,” and Pallares are all connected. Despite initial analyses, New Mexico’s peoples’ were disproportionately impacted by the Great Depression. The state was a place where migration from Mexico impacted the demographic makeup of local communities. Additionally, artists and reformers applied their idealized observations of Mexico in the 1920s to the day-to-day situation of nuevomexicanos and Native Americans in New Mexico. Based on their observation of Mexican efforts to bring indigenous peoples into the nation after the Mexican Revolution, reformers in New Mexico similarly patterned their educational and social reforms.

Their romanticized characterizations of New Mexico’s peoples as examples of an earlier, pre-industrial way of life subsequently skewed federal officials’ responses to the crisis of the Great Depression. Reformers, such as Mary Austin, Mabel Dodge Luhan, and John Collier, applied their conceptions of New Mexico as outsiders to address the crises faced in the state due to the Depression. Reformers’ understandings, however, missed the key issues facing New Mexico’s peoples. Despite the best efforts of reformers who hoped to reverse cultural and economic loss, the Great Depression negatively impacted New Mexico, just as it did most other locales throughout the nation. Reformers often misunderstood the key economic, social, and cultural problems in New Mexico, and therefore failed to address the needs of the people they most hoped to touch through New Deal programs.