The History of New Mexico

Collapse

Expand

-

Chapter 9: Territorial New Mexico

- Territorial New Mexico

- Civil War in New Mexico

- The Navajo Long Walk

- New Mexico as "Wild West"

- References & Further Reading

“This is why, this is why we are here,” Luci Tapahonso’s aunt told her. “Because our grandparents prayed and grieved for us.”9 As is the case for most, if not all Navajo people today, the Long Walk and the subsequent Treaty of 1868 remain a present fixture of their tribal, and personal, identity—despite the fact that nearly 150 years have passed.

Tapahonso wrote poems based on the stories told her by family members in an effort to preserve the horrors that her people faced in 1864 as they were forced to take the Long Walk from their homeland, the Dinétah, to the inhospitable Bosque Redondo on the Pecos River in east-central New Mexico. Between 1864, when over 8,500 Navajos arrived at Hwéeldi (their place of suffering), and 1868, when they were allowed to return home, about 2,500 of them died or were killed.

The Long Walk was the Navajo Trail of Tears—a tragic episode that illustrates the violence and cruelty of the U.S. conquest of the American West. The Treaty of 1868 was something of an anomaly in the history of relations between the U.S. government and Native American peoples. Unlike most other cases, the treaty guaranteed that the majority of the Diné homelands would remain under the purview of the tribe. Accordingly, Navajos still consider the Treaty of 1868 a moment of victory. Historian Peter Iverson has characterized the Long Walk as a “story of tears and triumph.”10

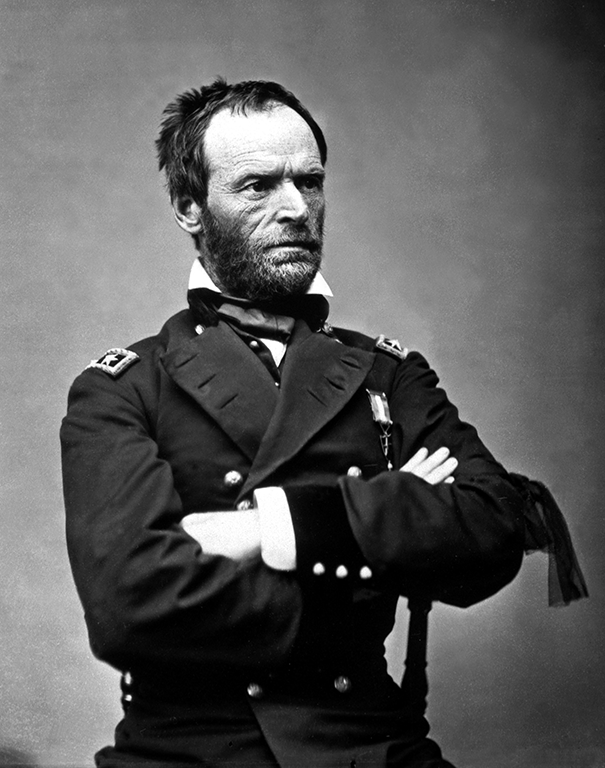

To understand this bleak portion of Navajo history, we must also examine the actions of those who worked to ensure that New Mexico become part of the United States, not only in terms of territory but also in terms of culture—something that U.S emissaries could never quite attain, no matter how hard they tried. Once the threat of a Confederate invasion had faded into the background, the military commander of the New Mexico department, General James H. Carleton, turned his attention toward dealings with Native Americans. Carleton arrived in the territory as the Brigadier General of the California Volunteers. He led the California Column, and in August of 1862 Carleton replaced Colonel Canby as commander of the district.

A career military man, Carleton wanted to see action in the fight against the Confederacy. His first commission had come at the age of twenty-five as a Lieutenant in the Maine Militia in 1838. In the early 1840s, he served at Fort Leavenworth and he accompanied Stephen Watts Kearny’s expedition to South Pass in 1845. During the U.S.-Mexico War, he fought in the battle of Buena Vista. Carleton was highly principled and rigid in his outlook on military procedure and protocol. Yet his tenure in New Mexico meant that he would not see action in any of the major battles of the Civil War.

Disappointed, Carleton poured all of his energy into alleviating what he and other U.S. military officers considered to be New Mexico’s “Indian problem.” According to journalist and historian Hampton Sides, he presided “over New Mexico virtually as a dictator” during his four years as military commander.11 Although he never took the title of military governor, Carleton instituted martial law throughout the territory and required residents to carry passports in an effort to locate Confederate sympathizers. Despite such efforts, his attempt to rid New Mexico of Confederates bore little, if any, fruit.

Carleton left his mark on New Mexico in the form of his attitude toward and treatment of Native Americans, particularly the Mescalero Apaches and the Navajos. Longstanding interactions between nuevomexicanos, Navajos, and Apaches were quite complex, including periods of peace punctuated by bursts of violence. Carleton, and many of the officers under his command, refused to understand the sophisticated relationship of indigenous people to the territory. Indeed, he “had little respect for Indians and viewed them as the main obstacle to stability in New Mexico.”12 Like so many other Americans of his time, Carleton was a proponent of Manifest Destiny. From his perspective, all indigenous peoples were “savages,” little more than hurdles to be overcome.

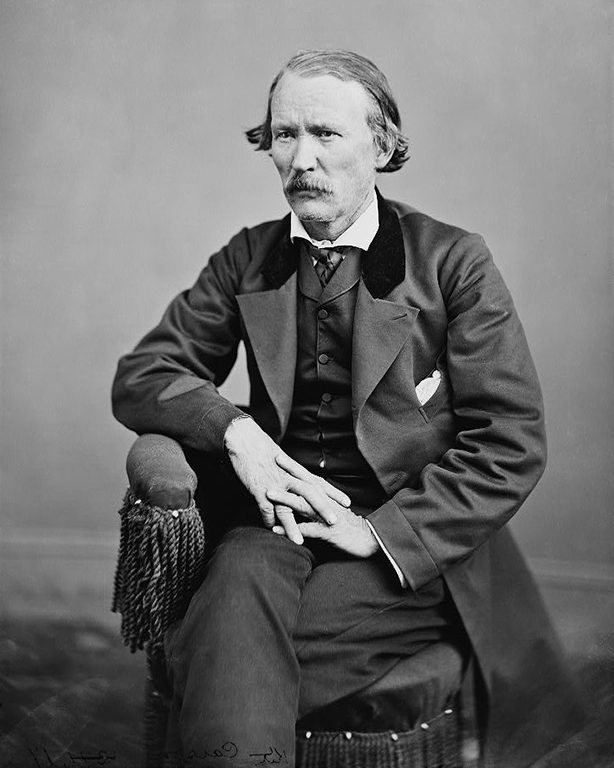

Courtesy of Library of Congress

Christopher “Kit” Carson, on the other hand, understood well the complexities of social relations in New Mexico and the larger American West. Despite his legendary status, his life was in many ways typical of Americans who migrated to New Mexico between the early 1820s and the 1840s. At the age of fourteen, after an unfulfilling stint as a saddle apprentice in Old Franklin, Missouri, Carson struck out for new fortunes in the West. The year was 1826. David Workman, his master saddle maker, offered one penny for his return in the October 6 edition of the Missouri Intelligencer. Offering a reward for escaped apprentices was common practice at the time, but the low value placed on Carson’s return suggests that Workman supported his decision to strike out on his own.

Over the next several years, as Carson came of age, he worked as a trapper in Taos, served as a Spanish interpreter in Chihuahua, learned the mining trade at Santa Rita, and then returned to beaver trapping in Arizona, California, and New Mexico. Contrary to what has become popular belief, he never vindictively targeted Native Americans. Instead, he was a product of his time and place. As historian Barton H. Barbour has shown, “If Carson once symbolized the positive aspects of America’s ‘great westward movement,’ he now epitomizes its negative aspects: the theft of Native Americans’ lands and usurpation of their sovereignty, the immoral American takeover of New Mexico, and so on.”13

Courtesy of Meeting of Frontiers and Library of Congress

Barton makes his case by invoking the concept of presentism. During Carson’s own lifetime, his role in expanding U.S. territory was applauded. Now, however, we have recognized the ways that the American conquest of North America destroyed native peoples and cultures. Although some today cast Carson as a “genocidal Indian Killer,” his relationships with Native Americans were far more nuanced.14 Like all peoples of the Mexican North (the American West after 1848), he understood that indigenous peoples harbored their own conflicts, took captives from other tribes, and either fought against or accommodated to the presence of people of European descent. Within that context, certain Native American bands were enemies, others were friends, and still others were neither. For Anglo Americans in the Mexican north, connections could be forged with hispanos while simultaneously maintaining a sense of American identity. Such was the milieu of Kit Carson.

Courtesy of SeeSpont Run

Indeed, over the course of his life Carson was married to two Native American women and one nuevamexicana, a woman from a prominent Taos family named Josefa Jaramillo. Their union produced eight children. Carson also served as U.S. Indian Agent for northern New Mexico between 1854 and 1861 when he joined the New Mexico Volunteers. Due to his extensive interactions with various indigenous peoples, he was better prepared for the post than most who were appointed to serve as Indian Agents. He took issue with Carleton’s characterization of all indigenous peoples as “savages.” Contrary to Carleton’s 1862 “shoot to kill policy” aimed at forcing Mescalero relocation to Bosque Redondo, Carson believed that the Apaches would instead make great allies of the Union in their battle against the Confederacy.

Still, Carson was a man of profound contradictions. Despite his experience with indigenous cultures, he felt a deep-seated sense of duty to his superiors. Despite his verbal knowledge of English, Spanish, and several indigenous languages, Kit Carson was illiterate. Additionally, he realized that he owed his national renown (he was the subject of popular dime novels during his own lifetime) to his association with John C. Frémont. Therefore, in 1862 when General Carleton called him up at the age of fifty-two to carry out a campaign against the Mescalero people, he could not say no.

By contrast, Navajo people understood their relationship to the United States in very different terms. Following the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, all of New Mexico transferred to U.S. jurisdiction, including the lands of the Navajos, Utes, Apaches, and Comanches. Yet no indigenous leaders attended the treaty negotiations or had any voice in the proceedings that ended the war. U.S. officials initiated a “process of dispossession” in New Mexico as soon as they occupied the territory in 1846.15 From the Navajo perspective, General Kearny’s promise to nuevomexicanos and Pueblos that the U.S. government would protect them from hostile nomads was akin to a declaration of war.

Kearny believed that a series of treaties could end long-standing conflict between Navajos and residents of the Rio Grande corridor. As was also the case with Mescalero and Chiricahua Apache bands, however, treaties actually compounded violence and resentment. Several factors contributed to that outcome. U.S. officials often assumed that when they made a treaty with one headman or band that they had made an agreement with the entirety of the tribe. Such was not the case. Additionally, many treaties were the result of duress. Military skirmishes such as the one that left chief Narbona dead in the fall of 1849 left Navajos no other choice than to sign proposed treaties.

The U.S. Senate ratified the treaty borne of that conflict, which allowed the U.S. government to establish military outposts on Navajo land, on September 9, 1850. Yet such an outcome was not typical. More often than not Congress refused to ratify documents that represented painstaking compromises between indigenous peoples and U.S. agents in the field. Following the murder of respected elder Narbona, his son-in-law Manuelito harbored anger and animosity toward the U.S. government. Along with Barboncito, he led efforts to remove Fort Defiance from Diné lands, after General William Thomas Harbaugh Brooks was appointed commander of the outpost in 1857 and following the failure of the Senate to ratify several proposed treaties. Brooks believed that the Navajos were too headstrong and that they “can only be prosperous when a strong arm, and one that they dread, is over them and ready to strike at any time.”16

In the early morning hours of April 30, 1860, one thousand Navajos followed Manuelito and Barboncito in a daring attack on Fort Defiance. Only the superior weaponry of the Third Infantry prevented the Navajos from taking control of the fort. Colonel Canby sought to force the removal of the Navajos from their homeland as punishment, but the Confederate threat forced him to turn his attention elsewhere. Instead, he signed a treaty with Barboncito, Manuelito, Armijo, and Ganado Mucho that defined an eastern boundary intended to prevent Navajo raids on New Mexican settlements. Once again, the Senate failed to ratify the pact. This repeating pattern of broken promises and misunderstandings perpetuated violence between the U.S. military and New Mexico’s independent indigenous peoples.

In the late 1850s, the practice of forcing Native Americans onto reservations gained traction at the national level. Carleton and other architects of U.S. Indian policy in the West conceived of reservations as places of protection and refuge for indigenous peoples. He envisioned the Bosque Redondo Reservation as a place where Mescaleros and Navajos would become literate in English, convert to Protestant Christianity, and develop a peaceful temperament. There, “the old Indians will die off and carry with them the latent longings for murder and robbing: the young ones will take their places without these longings: and thus, little by little, they will become a happy and contented people.”17 Additionally, Carleton wished to remove Navajos because, “based on no particular evidence,” Carleton also believed Navajo country to be resource rich.18

Such notions about the value and purpose of reservations were built on highly inaccurate assumptions about Navajo culture. Carleton pictured the Diné as an inherently warlike people with no true sense of connection to the lands they inhabited. Nothing could have been further from the truth. Navajos believed that the creator had placed them in the center of four sacred mountains, Blanca Peak, Mount Taylor, San Francisco Peaks, and Mount Hesperus. Similarly, the Mescalero and Chiricahua peoples held that the creator had granted sacred homelands to them as well. The cultural and social identity of each tribe was based on their connection to the land. Indeed, disconnection from the land often meant disconnection from tribal identity. Navajos rarely allowed rescued captives to re-enter their society.

Kit Carson’s campaign to remove them from the Dinétah was therefore an affront on various levels. First, under direction from Carleton, he waged war on the Mescaleros from his base at Fort Stanton. In 1862 about 400 families arrived at their new home on the Bosque Redondo, on the Pecos River in the shadow of the newly erected Fort Sumner. Driven by a sense of duty to Carleton, Carson remained deeply conflicted about the idea of forced relocation. Although privately he doubted the ability of Bosque Redondo to be a success, Carson was not one to voice such concerns.

In the early 1860s, Indian reservations were a new idea and those involved in their creation often referred to them as in the experimental stage. Looking to the earlier relocation of the Five Civilized Tribes as a precedent, Carleton singled out an area that he had visited in 1854 for the reservation site. As he traveled along the Pecos River, he encountered a region commonly referred to as Bosque Redondo. By his account, it was an ideal location for a fort because of its proximity to timber. He also described it as containing thousands of acres of arable land.

Courtesy of Center for Southwest Research, University Libraries, University of New Mexico (William A. Keleher Collection)

Despite Carleton’s recommendations, Bosque Redondo was none of those things. Even prior to the arrival of the Mescaleros and Navajos, a board of army officers tasked with finding a suitable reservation location issued a negative report. They found the site too remote from supply depots and too far removed from grazing lands. Virtually everything, including construction materials, food, fuel, and animals, would have to be shipped in at great expense. Also, their report stated that the water of the Pecos was not ideal for drinking and the valley was susceptible to seasonal flooding. In short, Bosque Redondo could not readily support a large population.

Carleton ignored such warnings and moved forward with his ill-conceived removal plan. Once Kit Carson had completed his campaign against the Mescaleros, he turned his attention to the Navajos. Realizing that the Diné would never leave the Dinétah willingly, he knew that he had to break their spirit as a people and attack the heart of their sacred homeland—Canyon de Chelly. As historian Peter Iverson reminds us, “although Carson has garnered most of the attention devoted to the effort to force the Diné into exile, he did not act by himself.”19 Due to conflicts between Navajos and Utes, he enlisted Ute scouts. He also relied on Zunis and Hopis for their detailed knowledge of local landscapes.

Beginning in the summer of 1863, Carson and his troops initiated a scorched-earth policy to break the will of the Navajos and force their surrender. Led by Ute scouts, they destroyed Navajo orchards and fields, and they killed their sheep and cattle. After leaving the Diné no means of subsistence, they returned to Fort Wingate to await their surrender.

In spite of such harsh measures, or perhaps because of them, far fewer Navajos turned themselves in at Fort Wingate than Carson had anticipated. Stories of abuse and even murder at the hands of the troops, combined with Carson’s indiscriminate tactics that targeted all Navajos, whether men, women, or children, whether hostile or willing to make peace, led most Diné to conclude that this was a campaign of extermination. Bi’éé Łichíí’í (Red Shirt, the name Navajos used for Kit Carson) seemed to offer no quarter.

Near the end of 1863 Delgadito became the first headman to lead his band of 187 people to Fort Wingate. After officially agreeing to Carson’s terms of surrender (relocate to Bosque Redondo or face death), he and three others traveled throughout the Dinétah with a message from Carson that if they moved to the reservation, the Diné would be left to live in peace. By the end of January 1864 Delgadito returned to the fort with 680 more people.

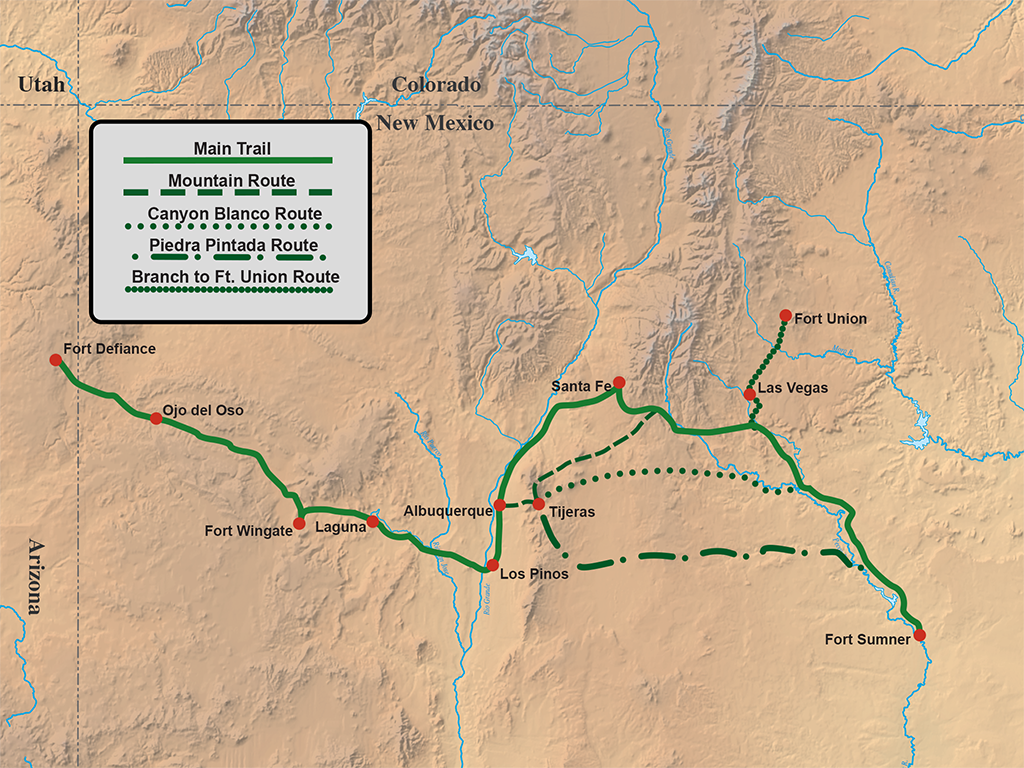

Although we speak of the Long Walk, in reality there were a series of forced marches that took place between August 1863 and late 1866. At times only a few people made the trek; in other instances hundreds did so. By one estimate, the largest single group numbered 2,400 people. Several different trails led from the Dinétah to Bosque Redondo, and the shortest among them covered a distance of 350 miles. The intense suffering endured along the trail and at Hwéeldi left an indelible mark on the collective and individual identities of Diné people. Given their options, however, most felt that they had no choice but to relocate. Over 8,000 people made the journey and nearly 2,500 died en route or in the squalid conditions of Bosque Redondo.

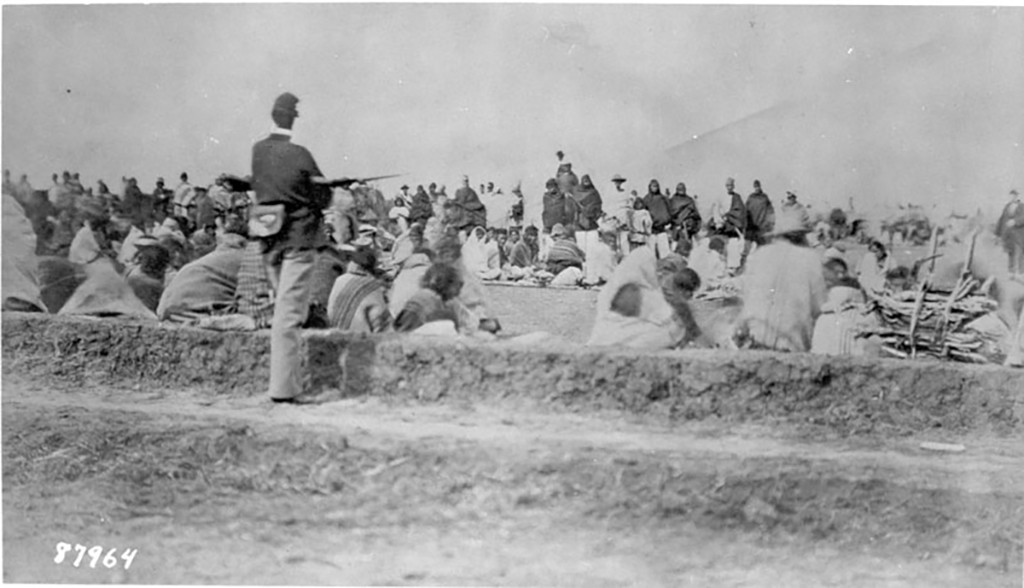

Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 001817

The Long Walk experience varied depending upon the size of the group and the whims and abilities of the officers in charge of the march. Some soldiers worked to protect those under their charge. Others took advantage of the Diné people. Those in the care of the largest groups often had no means of preventing attacks against the Navajos by nuevomexicanos and Pueblos. Nuevomexicanos and Pueblos along the Rio Grande corridor saw themselves as victims of Navajo raiding, and, to them, the Long Walk was a justified punishment. People across the territory targeted Navajos (and Apaches) for anything that went wrong.

“Several different trails led from Dinétah to Bosque Redondo, and the shortest among them covered a distance of 350 miles.”

In their oral traditions, some Diné admit that some among them frequently raided New Mexico settlements. Yet nuevomexicanos, Pueblos, and Anglo New Mexicans also participated in violent actions against the Navajos in their own country. Indeed, the countless campaigns in the Dinétah during the Mexican period highlight the long history of violence perpetrated by all sides. Still, with Carleton in charge of the New Mexico department and Kit Carson in the field, Navajos found themselves in an indefensible position. As they journeyed across the territory, most of them on foot and without sufficient provisions, they were defenseless against the retributive attacks waged against them.

If they survived attacks along the way, soldiers often added to the misery of leaving their sacred homeland by pushing them to travel at a faster pace than they were comfortably able. Certain officers gained reputations for marching them at a rate of about twenty miles per day. Many died under the stress. According to Curly Tso, “It was horrible the way they treated our people. Some old handicapped people, and children who couldn’t make the journey, were shot on the spot, and their bodies were left behind for the crows and coyotes to eat.” Others remember that some among them committed suicide rather than face death by starvation or freezing temperatures. Gus Bighorse told his children and grandchildren that “some families jump right down [tall cliffs] because they don’t want to be shot by the enemy. They commit suicide.”20 For Bighorse, witnessing the suicides was more difficult to bear than seeing other members of his party shot down by nuevomexicano raiders or the soldiers.

Diné women confronted sexual violence perpetrated against them by some of the soldiers that had been charged with their protection. Despite Carleton’s express order that the Navajos be safeguarded, the stark realities of a mission of expulsion and relocation meant that such could not be the case. Pregnancy and childbirth became an added burden. As Gus Bighorn remembered, “If a woman is in labor with a baby, she is killed.” Luci Tapahonso’s family memories recount the case of two women who were about to give birth and were thus unable to keep up with the group: “Some army men pulled them behind a huge rock, and we screamed out loud when we heard the gunshots. The women didn’t make a sound but we cried out loud for them and their babies.”21

Life in Hewéeldi provided no relief, despite Carson’s promise of peace in exchange for relocation. Carleton had anticipated 3,000 to 4,000 Navajos, but nearly 8,000 required support at Bosque Redondo. Problems abounded from the get-go. Traditionally, Mescaleros and Navajos had been enemies, something that Carleton apparently never considered. Tensions ran high as they attempted to live together in the 160-acre spread provided to them.

Inter-tribal tensions were eclipsed, however, by the poor living conditions at Hwéeldi. Army rations were not enough to support the nutritional needs of the people interned in the reservation, and, to make matters worse, Navajos were unaccustomed to cooking with items like white flour, beans, and coffee. The bacon they received was often rancid, creating conditions for disease to flourish and spread. Dysentery and other ailments spread among the population. As predicted by the army review board, the Pecos River contained highly alkaline water—under the best conditions it was undrinkable.

Despite Carleton’s assertion that Navajo people were “savage” or “barbaric,” in reality their lives in the Dinétah were far more “civilized” than those they were able to build in Hwéeldi. In November of 1865 Mescalero people fled into the surrounding mountains rather than face death in the reservation. Although most Navajo leaders, like Barboncito and Delgadito led the people to Hwéeldi, it is no wonder that others, like Manuelito, resisted. Recent research has shown that far more Navajos than previously thought stayed behind in the Dinétah.

Despite Carson’s fall 1864 assault on the sacred stronghold of Canyon de Chelly, Manuelito and hundreds of others fled to avoid capture. Historian Peter Iverson has shown that the percentage of Navajos removed to Bosque Redondo has been exaggerated. In the past, historians believed that virtually all Navajos made the trek to Bosque Redondo. Yet Manuelito and hundreds of others refused to submit. After years of resistance, lack of food and resources forced Manuelito to lead his band toward Hweeldi in 1866–one of the last Diné headmen to do so. A large number of other Navajos continued to resist.Although only about 1,000 or so in number, those who avoided relocation are remembered with pride by many Diné people. Oral traditions hold that those who remained in Monument Valley “conquered the United States.”22

Almost as soon as they arrived at Bosque Redondo, Navajo people looked to the time when they would return to the Dinétah. The creator had ordained those lands specifically for them, so, to them, the restoration of their homeland was a foregone conclusion. Navajo elders performed a ceremony in which the sign of the coyote indicated their return if they would but endure at Hwéeldi.

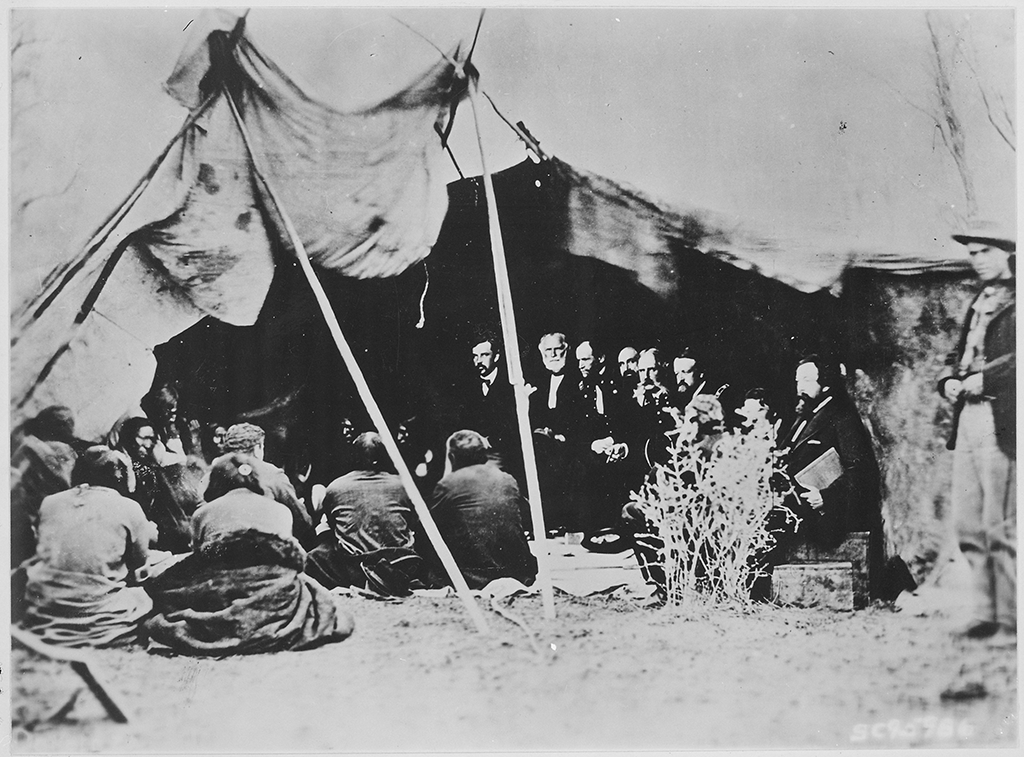

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

In 1866, Carleton was replaced as military commander of New Mexico Territory. Criticism from locals and Washington, D.C., politicians combined against him. Among the most damning evidence of his failure in the territory was the Bosque Redondo. When General William T. Sherman visited the reservation at the head of a peace commission to investigate conditions there in 1868, he found that all of the accusations against Carleton were justified.

Barboncito stepped forward as the spokesperson for negotiations with Sherman. Upon examination of Hwéeldi, Sherman sympathized with the plight of the Navajos, and he realized that the “experiment” at Bosque Redondo had to be abandoned. In the discussions of what was to become of the Diné, Barboncito delivered a moving speech in which he implored Sherman to send him and his people “to no other country other than my own.” In the end, they negotiated the Treaty of 1868 that provided for the return of the Diné to their homeland. Despite their pleas to guarantee to them the entire Dinétah, they instead received a large portion of their traditional homelands, a place they call the Diné Bikéyah. Despite the suffering that they endured, Navajos today take comfort in the reality that most indigenous peoples in the United States were completely removed from the lands endowed to them by their creators. The Treaty of 1868 placed the Diné in a position to rebuild a sense of tribal identity.

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

As a descendant of Mescaleros interned at Bosque Redondo recalled the significance of his ancestors’ resistance to removal, he commented, “the only thing we were doing was fighting for what was ours.”23 Such was the general feeling among those who had been removed to the Bosque Redondo. The Mescaleros escaped from the reservation and maintained their place in south central New Mexico Territory for the next decade. In the end, however, they were confined to reservation lands, albeit lands more hospitable than those along the Pecos River. The Navajo people, by contrast, continue to define their strength and resilience as a people by looking to the Treaty of 1868. Barboncito’s query to General Sherman says it all: they were returned to their sacred homelands, limited to a surprisingly small extent.