The History of New Mexico

Collapse

Expand

-

Chapter 8: U.S. Conquests of New Mexico

- U.S. Conquests of New Mexico

- War of North American Invasion

- "The Border Crossed Us"

- References & Further Reading

U.S. Political & Ideological Context

As early as the pre-revolutionary period, Americans looked to expand westward. Among British colonists’ many grievances against the government in London was the enforcement of the Proclamation of 1763, which forbade expansion beyond the Appalachian Mountains. Although the term Manifest Destiny was not coined until 1845 in John O’Sullivan’s work in the Democratic Review, the idea that the United States had the right to expand westward from ocean to ocean was nothing new. O’Sullivan placed a label on the expansionist emphasis of the political discourse that took shape during the Election of 1844. Prior to that time, sectional differences based on slavery expressly prevented the annexation of lands west of the Mississippi River. The fear was that the balance of free and slave states that had been struck by the Compromise of 1820, or Missouri Compromise, would be shattered if the United States expanded to the Pacific Ocean.

Once the United States gained its independence, slavery divided North and South. Many Northerners looked to the West as a means of perpetuating the Jeffersonian ideal of the yeoman farmer. Southerners hoped that the West would provide an opportunity to expand and solidify the institution of slavery as a viable economic system. Congressional negotiations, like the Missouri Compromise, maintained a tense unity between the states. The specter of westward expansion, however, promised to undermine the unquiet union. For precisely this reason, President Martin Van Buren refused Texas’ pleas for annexation in 1836.

Concerns about Oregon Territory and the potential annexation of Texas and California changed the calculus in 1844. By the early 1840s, the United States became more and more preoccupied with the Oregon Territory, part of an area which had been disputed by Russia, Spain, Britain, and the United States earlier in the century. An 1818 agreement between the United States and Britain allowed fur trappers from both nations to work in Oregon—by that time Russia and Spain no longer attempted to assert their claims. Most American settlers chose the Willamette Valley, between California and the Columbia River, for their homesteads. U.S. officials also hoped to secure Pacific ports along the Oregon coast to facilitate trade with China and other points in Asia.

A protracted economic downturn placed stress on people in what were then the western states following the Panic of 1837. Hard times acted as a push factor which prompted many to traverse the Oregon Trail in the early 1840s. A torrent of booster literature, including trappers’ and traders’ journals, missionary accounts, travelers’ accounts, reports financed by the government, and letters to friends and relatives from those already in Oregon contributed to the rise of “Oregon Fever.” Over 1,000 men, women, and children had undertaken the six month overland trek between Independence, Missouri, and the Willamette Valley by the late spring of 1843. Most of these people heralded from Missouri, Kentucky, and Tennessee, and they looked to Oregon as a place where they could make a new start as independent family farmers. Over the next two years, another 5,000 reached Oregon Territory.

Some of those who had intended to make their way to the Willamette Valley instead ended up in Mexican California, settling near Sacramento. Other Americans had arrived in the early 1830s both overland and by sea. As in the case of Oregon, booster literature targeted potential migrants to northern California. In the late 1830s, Alta California was only sparsely inhabited by Mexican citizens and indigenous peoples along the line of presidios and missions that had been established along the coast by Juan Bautista de Anza and others in the late 1700s.

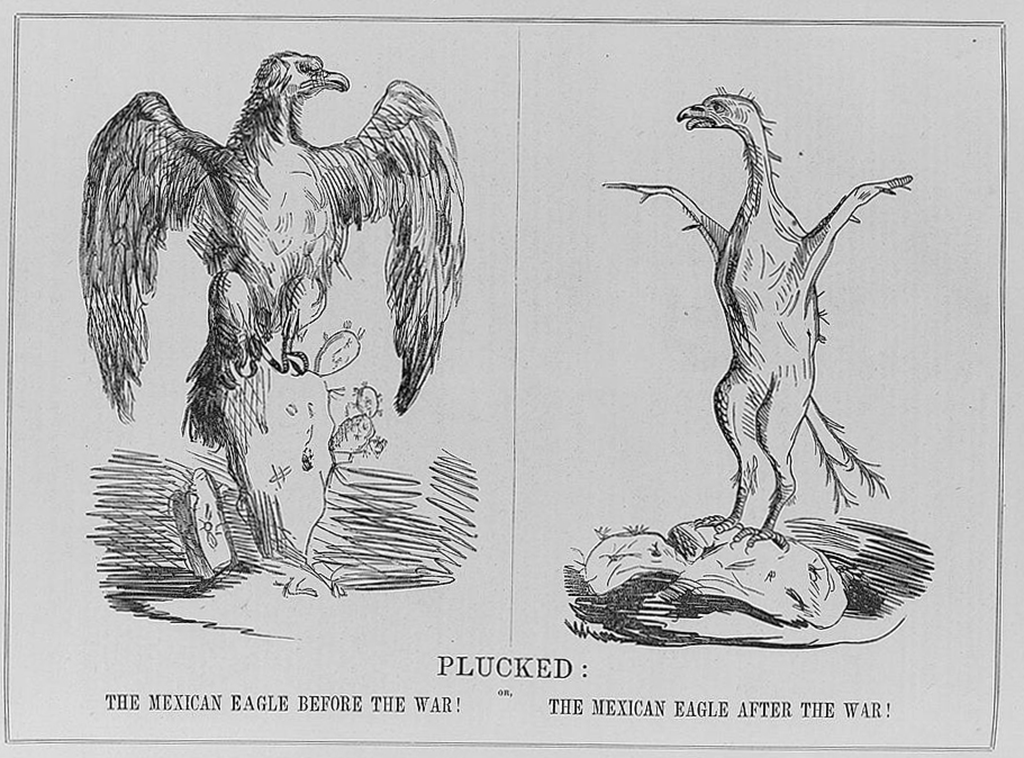

Courtesy of New York Public Library

As was the pattern in New Mexico and much of Mexico’s northeastern states, U.S. newcomers during the 1830s tended to adopt Mexican cultural and social patterns. Many intermarried into local rico and mestizo families in order to expand their stake in California cattle ranching, the main economic enterprise there. A few, like Thomas Oliver Larkin who arrived in California in 1832, plotted for eventual annexation to the United States. Generally, these men were either squatters or landowners of questionable legality. Larkin, on the other hand, had constructed a successful mercantile enterprise in Monterey. In 1843, he was named U.S. consul in the same city. He penned a series of letters that in part inspired a new wave of migration to northern California. Those who arrived between 1843 and 1846, however, were cut from a different cloth than earlier arrivals. They tended to arrive overland rather than by sea, and very few intermarried into californio families. Rather than integrate into the local culture, they stood apart—a development that seemed to play into Larkin’s dream of Americanizing the region.

“Our manifest destiny is to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions.”

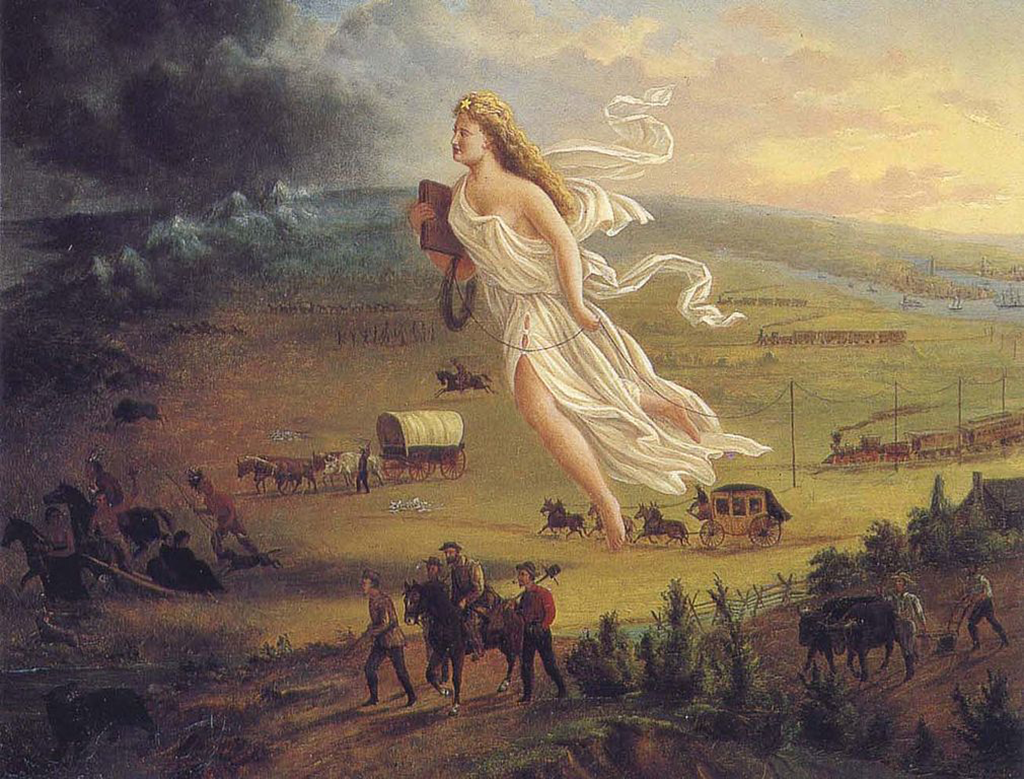

Migrations to Oregon and California coincided with the growth of a mentality of Manifest Destiny throughout the United States. Like all ideologies, Manifest Destiny was not all-pervasive in the 1840s, but it was quite influential. As defined by John O’Sullivan in the Democratic Review: “Our manifest destiny is to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions.”4 Manifest Destiny described the Unites States’ providential mission to extend its systems of democracy, federalism, and individual freedom to all between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Expansion across North America was ordained to accommodate the rapidly expanding population of the United States. O’Sullivan argued that the U.S. “true title” to the continent superseded any other nations’ or peoples’ competing claims to territory and resources based on prior discovery or settlement. Unlike many others, however, O’Sullivan insisted that the way to continental domination was to be peaceful through “Anglo-Saxon emigration.”5 Although not produced until 1872, John Gast’s “American Progress” offers a striking visual representation of the ideals of Manifest Destiny.

Painted by John Gast

Despite the growth of expansionist feeling due to migrations to Oregon and California, most Americans had not bought into Manifest Destiny during the first few years of the 1840s. Issues surrounding the potential proliferation of slavery kept westward expansion on the back burner. The electoral campaign of 1844 placed westward expansion front and center, however, and served to alter public opinion. As the election neared, rumors abounded that Britain wished to annex California to pay debts owed it by Mexico and that the British also had designs on Texas and Spanish Cuba. Fears of British incursions into North America caused Northern Democrats to call for an end to the joint occupation of Oregon, and Southern Democrats renewed their calls for the annexation of Texas. President John Tyler, who hoped for reelection on the Democratic ticket in 1844, championed a bill to annex Texas. With the prospect of Oregon entering the nation as a free state to maintain the balance of compromise, the Texas’ annexation became less controversial.

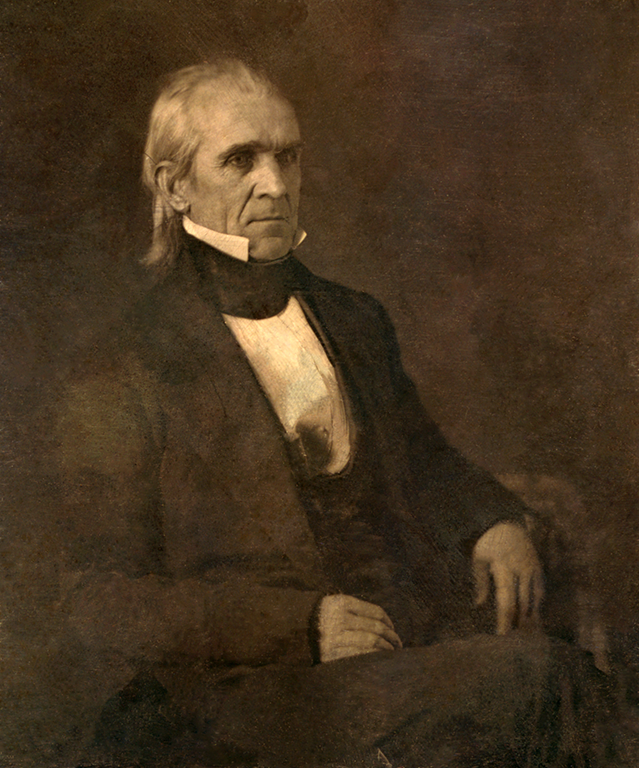

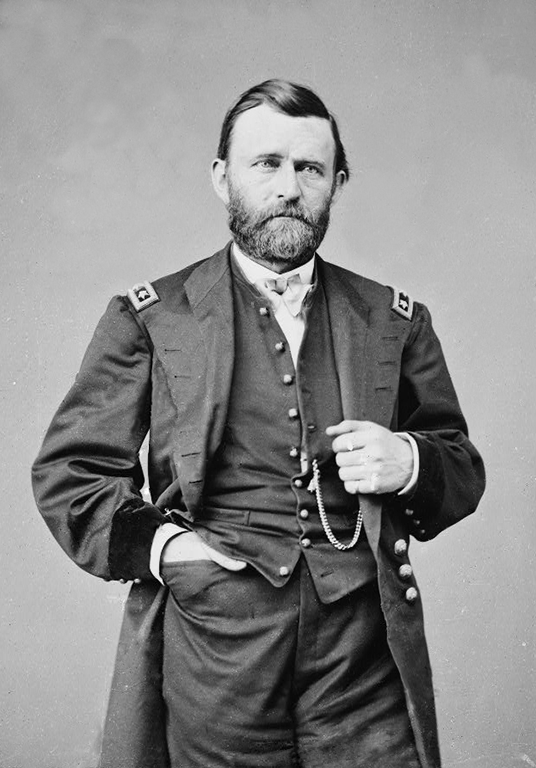

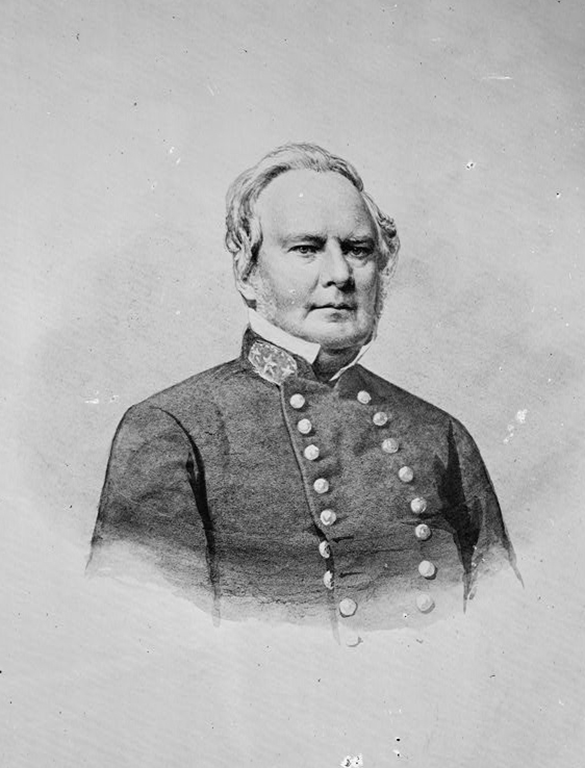

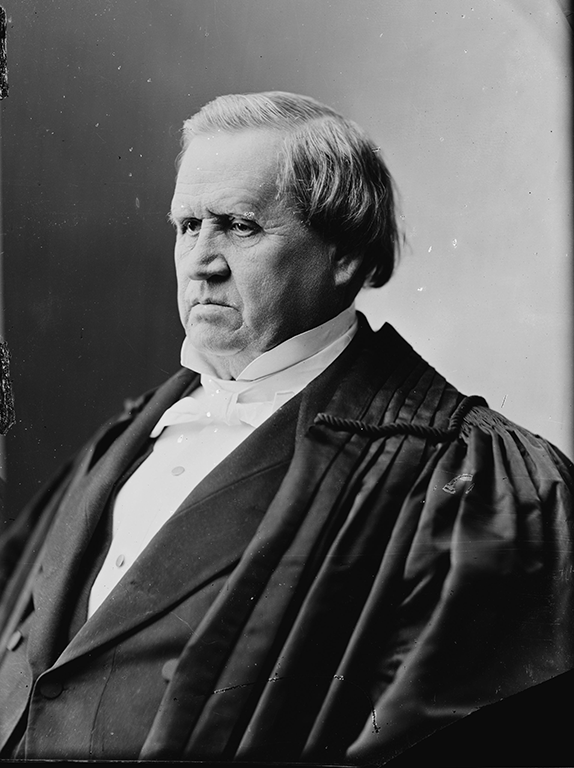

Courtesy of Matthew Brady

Unfortunately for Tyler, the Democratic Party passed him over in 1844. Instead, dark-horse candidate James K. Polk got the nod. Known as “Young Hickory” due to his personal and ideological association with Andrew Jackson (whose nickname was “Old Hickory”), Polk championed the cause of westward expansion as a candidate for the presidency. He was a Southerner, born in North Carolina and educated in law at the state university. As a young man, Polk moved to Tennessee where he established himself as a successful lawyer and planter. He also built a promising political career, spending fourteen years in Congress—four as Speaker of the House—and two years as governor of Tennessee. During the campaign, his slogan was “54° 40’ or fight!” He trumpeted his party’s assertion that both Texas and Oregon already belonged to the United States by virtue of the large Anglo-American populations in both regions.

Polk considered his victory over Whig Henry Clay to be a mandate on the Democratic Party’s expansionist platform. Over the course of his term in office, the United States expanded its boundaries to the Pacific Ocean, taking not only California, Oregon, and Texas, but also everything in between—the New Mexico Territory. As president, Polk’s intense ambition and work ethic took a physical toll. He died at the age of fifty-four, only three months after leaving office. The annexation of Texas was the spark that ignited the war of conquest that allowed for the realization of Polk’s expansionist proposals. John Tyler signed the bill for Texas’ annexation during his last days in office, and on December 29, 1845, Texas became a full-fledged state in the union.

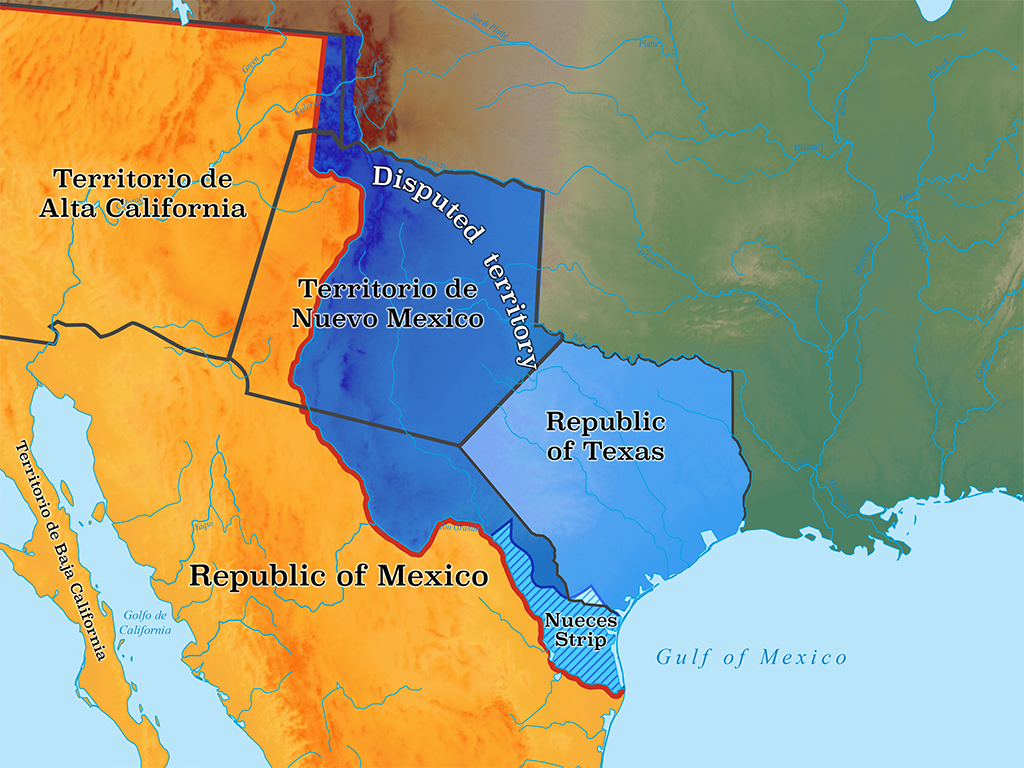

Origins of War

President Polk hoped to engineer a war with Mexico in order to realize his dreams of westward expansion. Texas’ claim on immense tracts of disputed land aided his efforts. Despite the dismal failure of the Texan-Santa Fe Expedition, the Republic of Texas had not relinquished its assertion that the Rio Grande formed its southern and western border. The Congress in Mexico City never ratified nor recognized the two Treaties of Velasco as legitimate, and held that the Nueces River was the southernmost extent of Texas territory. Even if Mexico had recognized Texas’ independence, it had been part of the dual state of Coahuila y Texas when it broke away from Mexico. Much of the disputed land was within the confines of the state of Tamaulipas. The territory in between the Nueces River and Rio Grande, known as the Nueces Strip, remained hotly contested up to the outbreak of war in May 1846.

The president did his best to keep the disputed nature of the Nueces Strip quiet. In July 1845, Polk sent General Zachary Taylor to the Nueces River with 3,500 soldiers under his command. At the same time, he sent John Slidell, a Congressman from Louisiana, to Mexico City with orders to negotiate the purchase of California and New Mexico for up to $30 million. As late as December 1845, however, Mexican officials refused to receive Slidell. They issued a statement that the annexation of Texas was illegal and that they would not treat with any representative of the nation that had perpetrated such an affront.

Polk predicted the outcome of Slidell’s mission and worked through other channels to achieve his ends. He hoped to sponsor an independence movement in California similar to that of Texas a decade earlier. Secretary of State James Buchanan advised Consul Thomas Oliver Larkin in Monterey to encourage Mexican residents of California to join American settlers in a declaration of independence from Mexico. Larkin was then to garner support for annexation to the United States. To support this covert proposal, John C. Frémont was dispatched on another exploration mission into California.

Courtesy of Mexicanec

All of the various pieces of Polk’s strategy initiated the gravitation toward war, but events did not move quickly enough for the president’s liking. In January 1846, before Mexican President José Joaquín de Herrera officially rejected Slidell’s diplomatic overtures, Polk ordered General Taylor to move his forces from their base at Corpus Christi to the northern bank of the Rio Grande—a highly provocative move. By late March, Taylor had positioned his men within striking distance of the Tamaulipas city of Matamoros. Mexican troops under General Pedro de Ampudia arrived shortly thereafter and announced their intentions to prevent further U.S. incursions into Mexican territory. The two generals exchanged diplomatic, though sharply worded, correspondence to assert their respective refusals to back down.

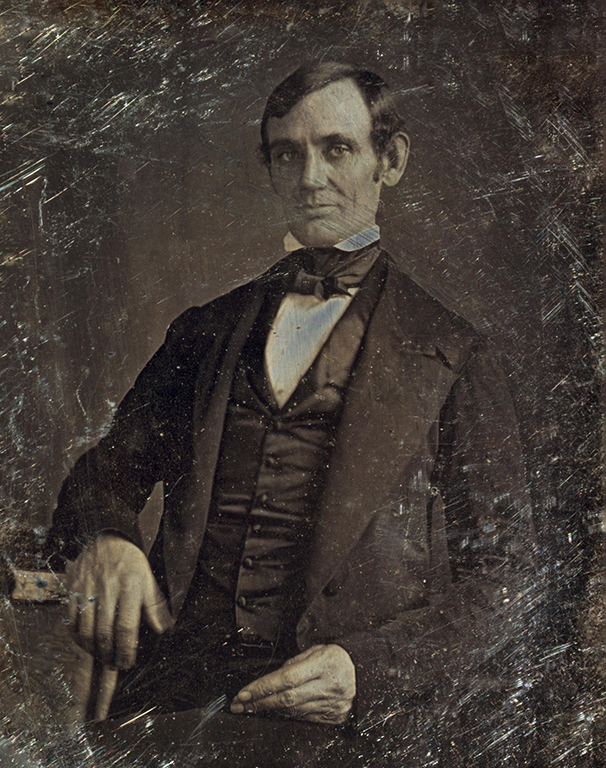

Courtesy of Library of Congress

In mid-April, Polk learned from Slidell that the purchase of California and New Mexico was impossible. Realizing that U.S. expansion could come only through war, the president grew increasingly impatient. General Taylor’s unstated purpose was to ignite a war with Mexico, but his presence so near Matamoros had not yet accomplished that end. As Ulysses S. Grant, who was among Taylor’s forces, later stated in his personal memoirs: “We were sent to provoke a fight, but it was essential that Mexico should commence it.”6 During his presidential term, Grant famously lamented that the nation had blood on its hands for initiating the war with Mexico. President Polk and many other Democrats in Congress, however, did not hold similar qualms against using war with their southern neighbor to achieve their expansionist goals.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

With no movement in the standoff between Taylor and Ampudia, Polk drafted a war speech and decided to take it to Congress anyway. Just before he did, news of a skirmish on April 25 between U.S. and Mexican forces that left “some sixteen [American soldiers] killed or wounded” reached Washington D.C.7 After hastily revising his speech, Polk approached Congress for a declaration of war. He framed the relationship between the United States and Mexico as one in which Americans had been forced to patiently endure a series of diplomatic, economic, and military abuses from its southern neighbor. Under such circumstances, and considering that “Mexico has passed the boundary of the United States, has invaded our territory, and shed American blood upon American soil,” a declaration of war was warranted.8 Despite some dissent from Whig Congressmen, including Representative Abraham Lincoln, Polk’s tactics proved effective, and the United States declared war on Mexico on May 13, 1846.

From the Mexican perspective, however, the situation looked quite different. Due to the controversy over the Nueces Strip, Mexican military and political officials alike considered their actions to be in defense against a U.S. invasion of their territory. Polk’s assertion that “American blood” had been shed upon “American soil” was untenable. Indeed, the title that has been given to the conflict south of the Rio Grande is telling. In Mexico, it is known as the “War of North American Invasion” or the “U.S. Invasion.” Following the U.S. declaration of war, most Mexicans echoed the sentiments expressed in the daily El Tiempo: “The American government acted like a bandit who came upon a traveler.”9 Many Mexicans attempted to arm themselves and join the effort to hold off the invasion, and most did not believe that the conflict would be as one-sided in favor of the United States as it proved to be. One of the major reasons for lopsided military contests was the reality that, for Mexico, the U.S. initiated a second war. As historian Brian DeLay has demonstrated, northern Mexico had already been devastated by the War of a Thousand Deserts. Under the circumstances, Mexican soldiers and citizens alike found it extremely difficult to repel U.S. forces.

U.S. “Occupation” of New Mexico

In August of 1846, Kearny led the [glossary_exclude]Army of the West[/glossary_exclude] into New Mexico. Governor Armijo had abandoned the forces organized to contest the Americans, and Kearny was able to take control of the region–at least nominally–without firing a shot.

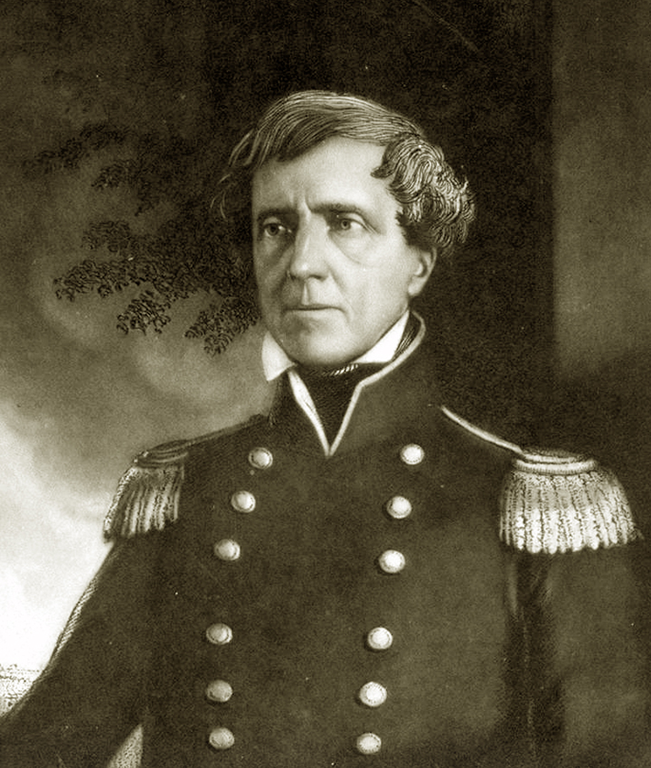

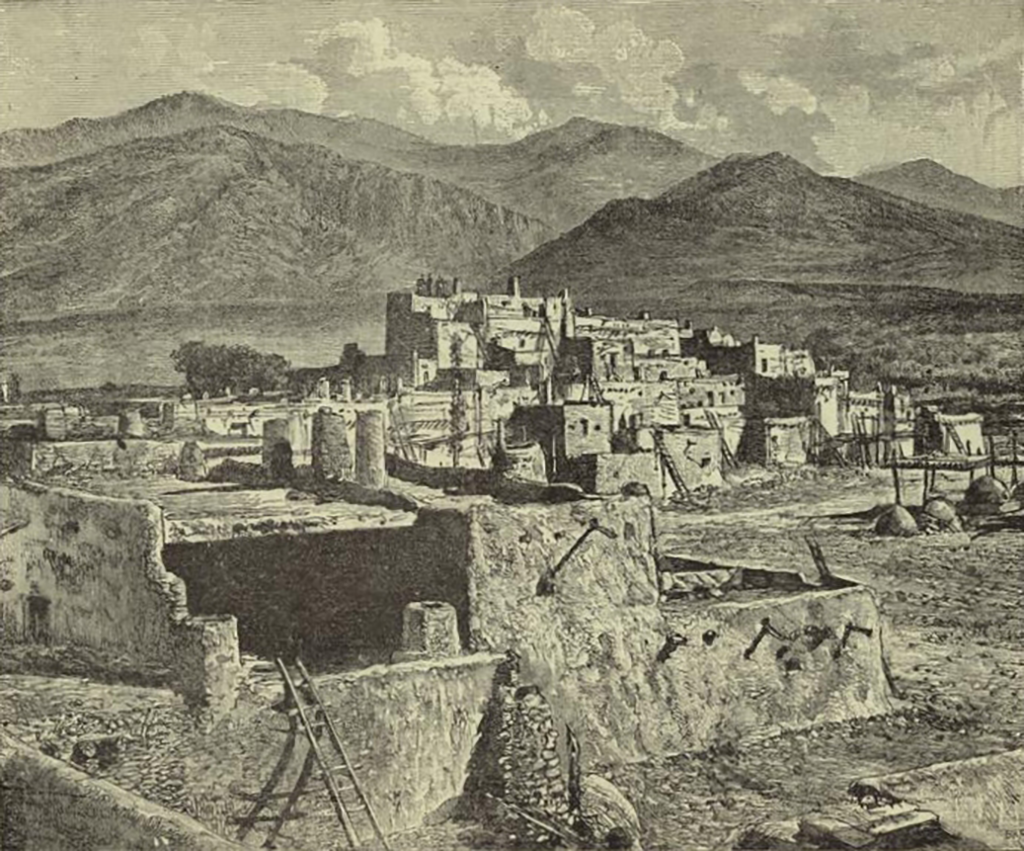

Engraved by Y.B. Welch for Graham’s Magazine

The conquest by Brigadier General Stephen Watts Kearny of Santa Fe on August 18, 1846, was marked as a bloodless event. While it was true that he was able to take possession of key New Mexico towns such as Las Vegas and the capital city without any major battles, recent scholarship has shown the idea of U.S. “bloodless occupation” of New Mexico to be a myth. Most nuevomexicanos were shocked and bewildered by the sweeping ability of the Army of the West to capture their department. After marching into Las Vegas on August 15, Kearny made a speech before the town. He promised that nuevomexicanos would be included in the actions of the U.S. republic from that day forth, and he leveraged local apprehensions about native attacks in his discourse. As recorded by William Emory, Kearny stated: “The Apaches and the Navajhoes [sic] come down from the mountains and carry off your sheep, and even your women, whenever they please. My government will correct all this.”10 As circumstances had it, the Army of the West arrived in Las Vegas not long after Navajo raiders had stolen its residents’ sheep and cattle. Kearny understood the impact of the War of a Thousand Deserts on nuevomexicanos, and he leveraged that knowledge to facilitate the conquest.

President Polk had hoped that the Army of the West could capture New Mexico without firing a shot. In an effort to protect the Santa Fe Trade and hasten the overall war effort, he ordered Kearny to occupy (rather than conquer) the territory. Due to this charge, many of the reports issued by Kearny and his men emphasized their means of “peaceful persuasion” in New Mexico.11 Their tenor contributed in part to the creation of the idea that most nuevomexicanos passively allowed, or even invited, the Army of the West to take control of their homeland. The writings of Santa Fe traders, principally Josiah Gregg, also provided fodder for early U.S. historians of the Southwest, such as Hubert Howe Bancroft, who sought to justify the U.S.-Mexico War with the ideology of Manifest Destiny. Their work ignored New Mexican sources and overlooked military reports that discussed nuevomexicano resistance.

Interestingly, the actions of Governor Manuel Armijo also contributed to the myth of bloodless occupation. As a beneficiary of the Santa Fe Trade, Armijo depended on the U.S. economy for his wealth. Yet he also had his own reputation to consider as the Army of the West approached Santa Fe. He had been riding high due to his capture of the Texan-Santa Fe expedition a few years earlier. The 1,600-man Army of the West, however, presented a far more formidable threat than the nearly 300 starving and dehydrated Texans. Although he led a group of 1,800 volunteers to meet Kearny on August 14, three days later Armijo decided to disband his forces and retreat to Chihuahua. Kearny marched into the capital city uncontested.

In a letter to Mexican President Mariano Salas, Armijo explained his actions.12 He argued that many of his volunteers had deserted and the trained officers agreed with his decision to retreat rather than mount a suicidal stand against Kearny. Armijo also cited the longstanding problem of military security in New Mexico and the north. He criticized Mexico City officials for failing to provide sufficient numbers of soldiers and armaments to defend against Navajos, Apaches, and Comanches in the years leading up to the U.S.-Mexico War.

Despite Armijo’s efforts to redeem his reputation, a group of prominent nuevomexicanos also wrote the Mexican president to condemn the former governor’s cowardice. They argued that Armijo had sufficient time to raise local militiamen and to request reinforcements from Chihuahua, but that the governor simply failed to act. According to their letter, most nuevomexicanos planned to resist the Army of the West but had been abandoned by their leader in the moment of necessity. Even Donaciano Vigil––who had counseled Armijo to retreat due to the superiority of the U.S. force––condemned him after the fact for abandoning New Mexico.

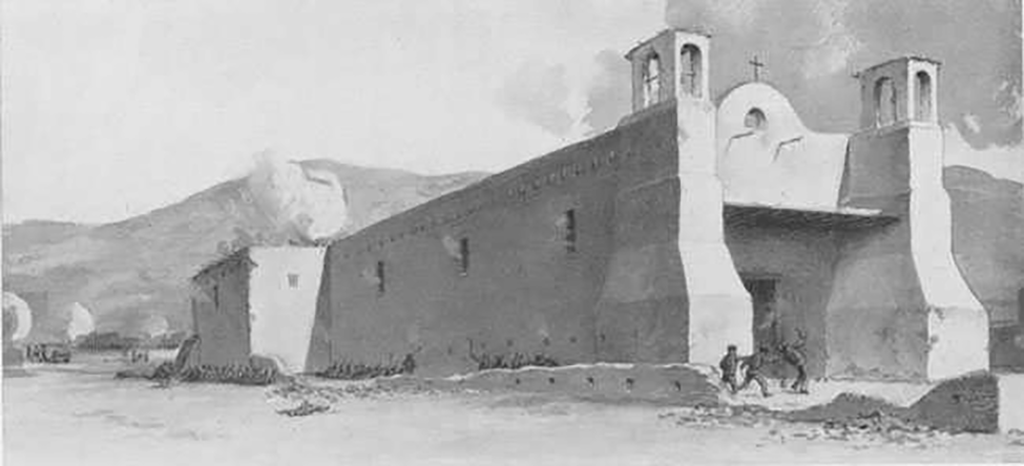

Painted by Henry Cheaver Pratt

The conflicting correspondence leaves many questions unanswered, and it seems that Armijo and prominent nuevomexicanos alike wrote for the purpose of justifying their own actions. If the New Mexicans had been willing to fight, why did they not do so despite Armijo’s retreat? On the other side of the situation, why did Armijo abandon New Mexico? His motives were much more complex and murky than his letter made them seem. In an effort to comply with Polk’s order to peacefully occupy New Mexico, Kearny enlisted the aid of the well-connected trader James Magoffin. Magoffin and Armijo knew one another personally, and they held a closed-door meeting in late July or early August that also included the governor’s second-in-command, Diego de Archuleta. Magoffin’s mission was to persuade Armijo to surrender Santa Fe without a fight. Archuleta reportedly was incensed at the offer and he nearly persuaded Armijo to walk out of the meeting. Rumors abounded at the time (and in later historians’ accounts) that Archuleta and Armijo received a bribe from Magoffin to allow Kearny to take control of New Mexico.

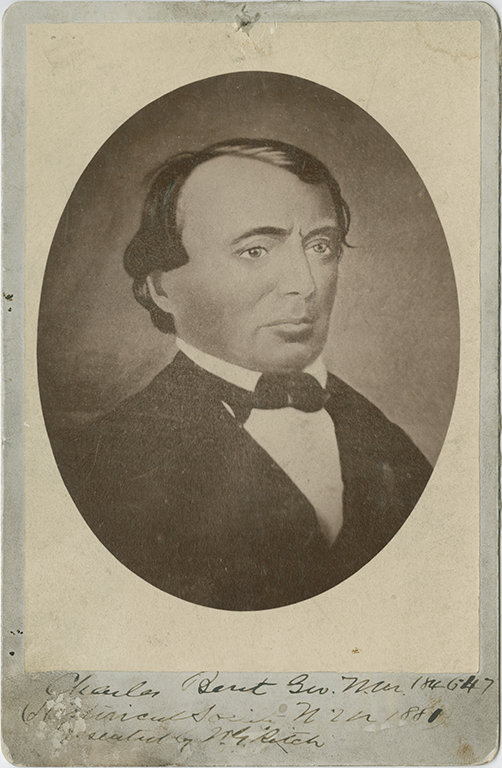

Courtesy of New Mexico Magazine Archival Collection

Whatever their reasoning, Kearny established a military government in New Mexico which displaced nuevomexicanos in favor of Anglos at the territorial level. At the local level, Kearny worked to ensure the continued leadership of existing ayuntamientos, alcaldes, and judges. Charles Bent, partner with his brother William in Bent’s Fort on the Santa Fe Trail, was named governor under the Kearny Code which went into effect as the legal code for U.S.-occupied New Mexico on September 22, 1846. Governor Bent had a family in Taos with his wife, María Ignacia Jaramillo, an older sister of Josefa Jaramillo, Christopher “Kit” Carson’s wife. Indeed, Bent had informed Kearny that Armijo would be hesitant to fight the Americans if he did not receive reinforcements from Chihuahua or Sonora. Bent’s role in Kearny’s diplomatic maneuvering was well rewarded.

Armijo’s Lieutenant Governor, Juan Bautista Vigil y Alarid, hesitantly accepted Kearny’s occupation of Santa Fe. In a tone that inferred his desire to defy the superior Army of the West, Vigil y Alarid pointed out that his people would let officials in Washington D.C. and Mexico City formally decide whether or not they were to become U.S. citizens, as Kearny had proclaimed. Historians Robert J. Rosenbaum and Carlos R. Herrera have argued that Vigil y Alarid chose accommodation as a form of resistance, whereas Armijo decided to withdraw in order to fight another day. Rosenbaum has outlined a continuum of nuevomexicano resistance which ranged from acts of withdrawal, to accommodation and assimilation, to outright armed revolt. Because withdrawal and accommodation can also be considered forms of submission, nuevomexicano resistance to the U.S. occupation tended to be overlooked.13

Courtesy of Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), No. 152218

Donaciano Vigil and Antonio José Otero were the only nuevomexicanos to serve in the territorial government under the Kearny Code. Vigil and Vigil y Alarid had aided Kearny and his advisors in drawing up the legal code. Vigil was named secretary under Governor Bent, and Otero served as one of the territory’s judges. All of the other territorial-level posts, however, were granted to friends and associates of Charles Bent who lived in and around Taos. Despite Vigil and Otero’s efforts to use their posts to preserve their culture under U.S. rule, most other nuevomexicanos were infuriated by the new government that had not allowed for any type of democratic process. Kearny appointed all of the leaders to their positions and shortly thereafter moved on to aid the war effort in California, with Kit Carson as his guide.

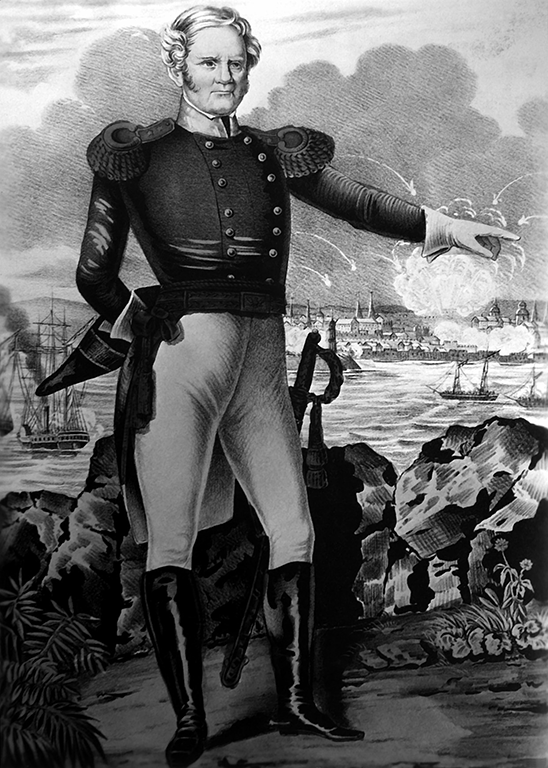

Courtesy of Library of Congress

Colonel Sterling Price remained in Santa Fe with a small contingent of troops to maintain peace. Most nuevomexicanos in rural areas removed from Santa Fe adopted a form of withdrawal to deal with U.S. rule. They attempted to ignore the new administration and continue with their lives as normally as possible under the circumstances. Almost immediately after Kearny left New Mexico, conditions grew increasingly unsettled. Padre Antonio José Martínez openly opposed the U.S. conquest and he was a target of Governor Bent’s ire due to his opposition to land grants that had been generously given to American traders in the new governor’s social circle.

In his reports to his superiors during 1846 and 1847, Colonel Price repeatedly underscored smoldering unrest just beneath the surface in New Mexico. The clearest evidence of open nuevomexicano resistance to the American takeover is found in Price’s correspondence and in communications between nuevomexicano rebels and Mexico City officials. In October 1846, for example, Tomás Ortiz and Diego de Archuleta outlined their plans for a general uprising to begin on December 19. In an effort to garner more support, they pushed the date back to December 24. In the meantime, the group organized its own shadow government with Ortiz as governor and Archuleta as military commander.

The plot was quashed before it began when Donaciano Vigil learned of the planned insurrection. Most of the instigators were arrested, but Ortiz and Archuleta managed to escape and unrest continued. Governor Bent declared the affair resolved in early January, however, and ordered all residents to avoid any future plans for rebellion. Support for armed resistance was widespread; figures like Padre Martínez and Archuleta who represented a sector of the rico elite, combined with mestizos from Taos (including Manuel Cortez and Pablo Montoya), people from Taos Pueblo, and, by the summer of 1847, some Apache bands all joined the armed resistance to U.S. occupation of New Mexico.

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Despite Governor Bent’s proclamations, revolt erupted in northern New Mexico in mid-January. Underestimating the magnitude of the hostilities, Bent traveled to his Taos home to personally address the unrest. On January 19, 1847, a force led by Pablo Montoya, “the self-styled Santa Anna of the north,” and Taos Pueblo headman Tomasito killed Bent in his own home in the presence of his wife and children. Six other Anglo territorial officials met their deaths during what came to be known as the Taos Revolt. The insurgents also worked to destroy land-grant documentation in order to revert local lands and resources to nuevomexicano communities.

Courtesy of Az81964444

Some historians have characterized the Taos Revolt as a massacre separate from the unsuccessful December plot. Yet revisionists have illustrated that the subsequent actions of those involved in the Taos insurrection indicate that their primary goal was to thwart U.S. control of New Mexico. The day after Bent’s assassination, General Jesús Tafoya issued a formal declaration of war against the United States on behalf of the Rio Arriba region. That same day Colonel Price also found evidence of a planned insurrection in Rio Abajo. In response, Price moved to head off the Taos rebels with 353 men and four howitzer cannons.

The two sides met at La Cañada, where five hundred nuevomexicanos stood against Price. Despite their superior numbers, they lost the day and Tafoya was counted among the dead. In February, nearly seven-hundred nuevomexicanos again challenged Price at Embudo Pass. This time, they were able to force the Americans to retreat to Taos where Price confronted another rebellion at the Pueblo. After a heated battle, Price’s forces emerged victorious. The best estimates indicate that about two-hundred nuevomexicanos lost their lives in confrontations with Colonel Price during the first two months of 1847. Pablo Montoya was executed following the Battle of Taos, and eight other rebels were convicted of treason and hanged as well. They were tried in the court system established by the Kearny Code, which meant that the jury was dominated by Anglo newcomers. Following the executions, President Polk formally reprimanded Price for his actions. Because the United States and Mexico were still at war, the Taos insurgents should have been treated as prisoners of war, not tried for treason. Despite Kearny’s pronouncement of U.S. citizenship for nuevomexicanos, they could not legally be considered such until the territory was officially incorporated into the nation by the U.S. Congress.

Despite Price’s swift suppression of the uprising, the insurgency continued through the summer and early fall of 1847. As violence erupted between the Taos insurgents and Price’s force, Manuel Cortez instigated a guerrilla war from his home in Mora. Reinforcements under the command of Jesse I. Morin arrived in Mora in early February to quell dissension there. From the surrounding mountains, Cortez and his supporters raided Morin’s army rather than attempt to face them in a head-on conflict. After a few weeks of guerrilla fighting, Morin ordered the execution of captured rebels and laid waste to the town of Mora. His forces burned wheat fields in surrounding areas to prevent Cortez’s men from subsisting off of the land. After the annihilation of the town, Morin led his men back to Santa Fe.

Cortez did not give up the fight, however, and he began to recruit native allies, including Apache people. Their raids on U.S. camps inspired retaliation against nuevomexicano villages which frequently resulted in the deaths of civilians. Such actions further solidified anti-American sentiment in the region and sharpened Cortez’s resolve. By August 1847 U.S. military officials far from New Mexico declared that the conflict was over, but Colonel Price knew better. He learned that Cortez had received a commission from the Mexican government to continue the struggle and that a large army was taking shape in Chihuahua for the purpose of moving against Santa Fe. Although war preparations in both Chihuahua and Durango continued for the next few months, such efforts came to naught when U.S. and Mexican officials signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in February of 1848.

Although the efforts of Cortez, Montoya, Tomasito, and Tafoya failed to reverse the U.S. conquest of New Mexico, their continued struggle provides clear evidence of nuevomexicano resistance. Kearny’s keen diplomacy did allow for the bloodless occupation of Santa Fe in August 1846, but that single event did not mean that nuevomexicanos were willing to accept conquest without a fight. Even after the ratification of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, nuevomexicanos, Pueblo peoples, Apaches, and Comanches persisted in their struggle to maintain their cultures and identities as residents of a U.S. territory.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

By early 1847, U.S. troops controlled most of northern Mexico. Although Mexican forces were able to win some important battles, the devastation wrought by the War of a Thousand Deserts played a major role in preventing them from turning the tide in the overall war effort. U.S. military and political officials debated different means of forcing the Mexican government to capitulate. Initially, they hoped that victories throughout the Mexican north would be sufficient to force negotiations in Mexico City. Even after California was captured in the fall of 1846 and the vital ports of Tampico and Veracruz fell under U.S. control, the Mexican people were unwilling to concede defeat. Any politician who attempted to negotiate would have appeared weak and unpatriotic.

Courtesy of U.S. Army (NARA 111-SC-4969992)

Within that context, Antonio López de Santa Anna was able to mount a brief resurgence in the arena of public opinion with his campaigns against Taylor’s forces in the north. Political unrest in Mexico City, however, forced him to return to the capital to resolve the turmoil before moving against U.S. forces. Although Mexican military and political officials faced opposition and defeat on all sides, they continued to hold out. By early 1847, General Winfield Scott led 14,000 men from the port city of Veracruz in a campaign to capture Mexico City. Along the way, some of the men read History of the Conquest of Mexico by Walter H. Prescott and imagined themselves on a mission similar to that of Hernán Cortés. Several of Scott’s officers, such as P. G. T. Beauregard, Robert E. Lee, and George Meade, were trained at West Point and later rose to notoriety during the U.S. Civil War.

On September 12 and 13 of 1847, Scott’s forces waged the Battle of Mexico City, which resulted in the defeat of Mexican forces and the U.S. occupation of the Mexican capital. Famously, during the assault on Chapultepec Castle, Mexico’s school for military cadets, several teenage boys gave their lives when they refused to retreat before the American onslaught. Today, they are remembered as los niños heroes (the boy heroes), and their memory is preserved with a large monument in Chapultepec Park.

Photograph by Thelmadatter

Santa Anna’s loss of Mexico City once again undermined his political power and he was forced to resign. An interim government was left to decide what measures to take. Despite Scott’s victory, guerrilla warfare continued in the streets of the capital and American casualties continued. Leaders of the liberal faction of Mexican politics, which had descended from the Federalist cohort of pre-war years, including influential figures like future president Benito Juárez, Melchor Ocampo, and Ponciano Arriaga, urged continued resistance. Ocampo said, “give the people arms and they will defend themselves.” At the same time, peasant rebellions broke out across Mexico alongside continued resistance against U.S. troops. Mexico City leaders favored a quick settlement with the United States in order to prevent a widespread peasant uprising. As historian Leticia Reina summarized the issue: “The Mexican government preferred coming to terms with the United States rather than endanger the interests of the ruling class.”14

As a result, Mexico ceded California, New Mexico, and Texas under the terms of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, an area that represented nearly half of Mexico’s national territory. The treaty itself was the result of tense negotiations between American representative Nicholas Trist and Bernardo Couto, Miguel Atristain, and Luís Gonzaga Cuevas who were members of a special commission to represent Mexico’s interim government which had formed at Querétaro. Although President Polk pushed Trist at the eleventh hour to negotiate for all of Mexico’s territory and even attempted to recall him, the negotiations had already been completed and the document signed on February 2, 1848. In exchange for the ceded territory, the United States paid Mexico an indemnity of $15 million.

From the perspective of the Mexican commission, Article VIII,Article IX, and Article X were the most important elements of the treaty. They specifically addressed the rights of Mexican citizens living in the ceded territories. Although it appeared to some that the Mexican government had left those people to their own devices, the representatives sought to protect their rights as best they could through the treaty itself. Article VIII guaranteed Mexicans living in the ceded territory the right to retain their homes and property. They were given a period of one year to decide whether to retain Mexican citizenship or to become U.S. citizens. If they made no such declaration within the year, they would become American citizens by default. Either way, the article was designed to allow them the continued rights of full citizenship.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

Article IX stipulated that those who elected to become U.S. citizens would be “incorporated into the Union . . . and be admitted, at the proper time . . . to the enjoyment of all the rights of citizens of the United States.”15 In the meantime, they would be allowed to practice the Catholic faith without interference, a major concern of the negotiators, and enjoy liberty and property rights. The Mexican commission’s original draft included clearer phrasing that specified all Mexicans to be treated as the equals of other American citizens at all times, but those stipulations were omitted by the U.S. Congress during the ratification process. Article X directly addressed Spanish and Mexican land grants in the ceded territories. It stipulated that all such grants remain intact as outlined by Spanish or Mexican law. The U.S. Congress, however, struck Article X from the treaty as one of the terms of ratification.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

Alterations in place, the U.S. Congress ratified the treaty on March 10, 1848. Although Mexican officials questioned Nathan Clifford, the U.S. Ambassador to Mexico, about the alterations, the Mexican Congress also ratified the treaty shortly thereafter on March 19, 1848. Ratification passed by the narrowest of margins: it was approved by one vote. A memorandum of understanding, titled the Querétaro Protocol, arranged between Clifford and Mexican negotiators convinced many Mexican legislators that the interests of their fellow citizens in the ceded territories would be guaranteed despite the changes to the treaty. Others were not so sure. Ultimately, after the crushing defeat in the war, Mexican policymakers believed that they were in no position to challenge the treaty. As the detractors had feared, American officials ignored the Quéretaro Protocol once official dealings concluded.