Learning Objectives

Describe the major developmental theories in lifespan development

- Use psychodynamic theories (like those from Freud and Erikson) to explain development

- Explain key principles of behaviorism and cognitive psychology

- Describe the humanistic, contextual, and evolutionary perspectives of development

Understanding Theories

A theory guides and helps us interpret research findings as well. It provides the researcher with a blueprint or model to be used to help piece together various studies. Think of theories are guidelines much like directions that come with an appliance or other object that required assembly. The instructions can help one piece together smaller parts more easily than if trial and error are used.

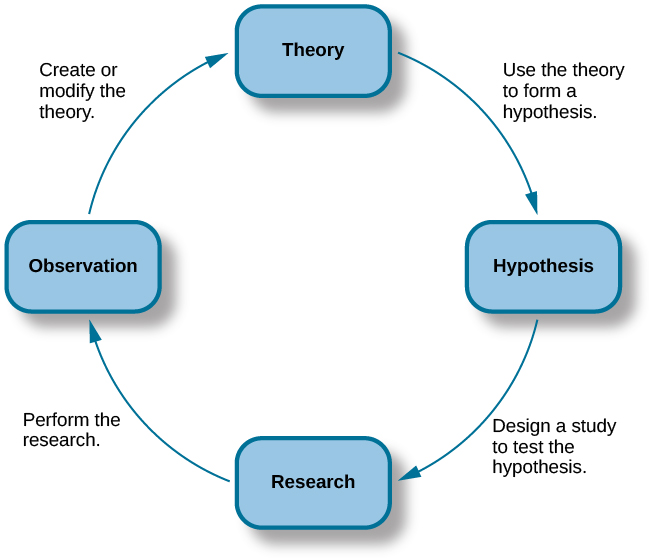

Theories can be developed using induction, where a theorist observes a number of single cases to determine patterns or similarities and then uses these observations to develop new ideas based on those examples. Established theories are then tested through research; however, not all theories are equally suited to scientific investigation. Some theories are difficult to test but are still useful in stimulating debate or providing concepts that have practical application. Keep in mind that theories are not facts; they are guidelines for investigation and practice, and they gain credibility through research that fails to disprove them.

What is a theory?

In lifespan development, we need to rely on a systematic approach to understanding behavior, based on observable events and the scientific method. There are so many different observations about childhood, adulthood, and development in general that we use theories to help organize all of the different observable events or variables. A theory is a simplified explanation of the world that attempts to explain how variables interact with each other. It can take complex, interconnected issues and narrow it down to the essentials. This enables developmental theorists and researchers to analyze the problem in greater depth.

Two key concepts in the scientific approach are theory and hypothesis. A theory is a well-developed set of ideas that propose an explanation for observed phenomena that can be used to make predictions about future observations. A hypothesis is a testable prediction that is arrived at logically from a theory. It is often worded as an if-then statement (e.g., if I study all night, then I will get a passing grade on the test). The hypothesis is extremely important because it bridges the gap between the realm of ideas and the real world. As specific hypotheses are tested, theories are modified and refined to reflect and incorporate the result of these tests. In essence, lifespan theories explain observable events in a meaningful way. They are not as specific as hypotheses, which are so specific that we use them to make predictions in research. Theories offer more general explanations about behavior and events.

Think of theories as guidelines, much like directions that come with an appliance or other object that required assembly. The instructions can help one piece together smaller parts more easily than if trial and error are used.

People who study lifespan development approach it from different perspectives. Each perspective encompasses one or more theories—the broad, organized explanations and predictions concerning phenomena of interest. Theories of development provide a framework for thinking about human growth, development, and learning. If you have ever wondered about what motivates human thought and behavior, understanding these theories can provide useful insight into individuals and society.

Throughout psychological history and still in the present day, three key issues remain among which developmental theorists often disagree. Particularly oft-disputed is the role of early experiences on later development in opposition to current behavior reflecting present experiences–namely the passive versus active issue. Likewise, whether or not development is best viewed as occurring in stages or rather as a gradual and cumulative process of change has traditionally been up for debate – a question of continuity versus discontinuity. Further, the role of heredity and the environment in shaping human development is a much-contested topic of discussion – also referred to as the nature/nurture debate. We’ll examine each of these issues in more detail throughout the course.

Psychoanalytic and Psychodynamic Perspective

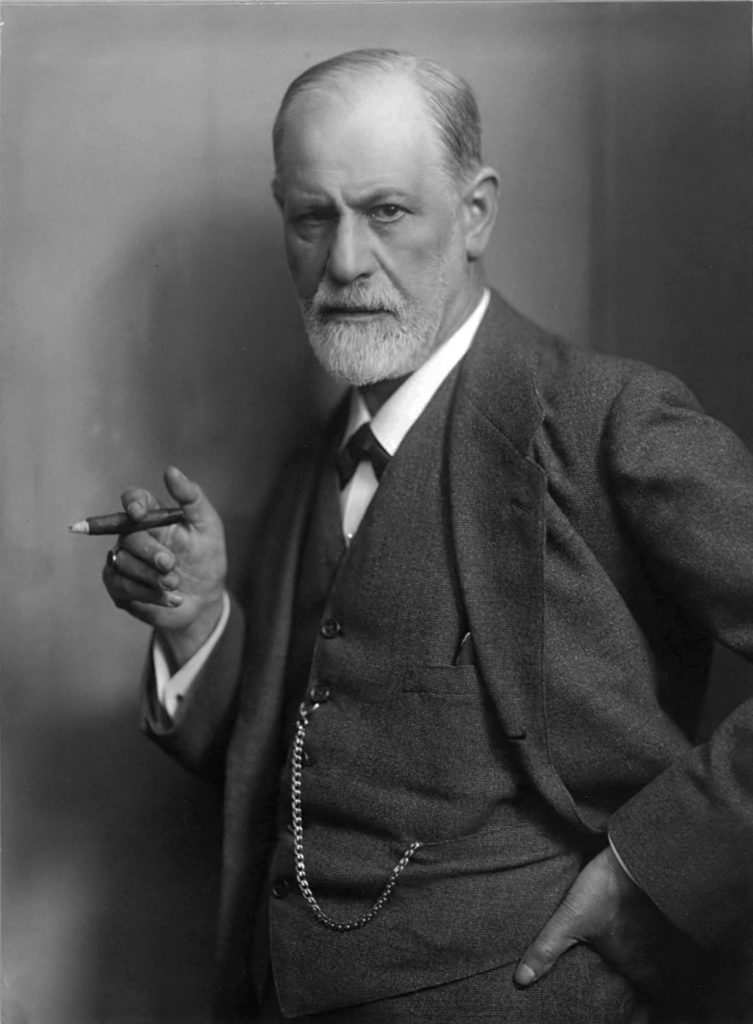

Sigmund Freud

Another name you are probably familiar with who was influential in the study of human development is Sigmund Freud. Sigmund Freud’s model of “psychosexual development” grew out of his psychoanalytic approach to human personality and psychopathology. In sharp contrast to the objective approach espoused by Watson, Freud based his model of child development on his own and his patients’ recollections of their childhood. He developed a stage model of development in which the libido, or sexual energy, of the child, focuses on different “zones” or areas of the body as the child grows to adulthood. Freud’s model is an “interactionist” one since he believed that although the sequence and timing of these stages are biologically determined, successful personality development depends on the experiences the child has during each stage. Although the details of Freud’s developmental theory have been widely criticized, his emphasis on the importance of early childhood experiences, prior to five years of age, has had a lasting impact.

Erikson’s Psychosocial Theory

Now, let’s turn to a less controversial psychodynamic theorist, the father of developmental psychology, Erik Erikson (1902-1994). Erikson was a student of Freud’s and expanded on his theory of psychosexual development by emphasizing the importance of culture in parenting practices and motivations and adding three stages of adult development (Erikson, 1950; 1968).

Background

As an art school dropout with an uncertain future, young Erik Erikson met Freud’s daughter, Anna Freud, while he was tutoring the children of an American couple undergoing psychoanalysis in Vienna. It was Anna Freud who encouraged Erikson to study psychoanalysis. Erikson received his diploma from the Vienna Psychoanalytic Institute in 1933, and as Nazism spread across Europe, he fled the country and immigrated to the United States that same year. Erikson later proposed a psychosocial theory of development, suggesting that an individual’s personality develops throughout the lifespan—a departure from Freud’s view that personality is fixed in early life. In his theory, Erikson emphasized the social relationships that are important at each stage of personality development, in contrast to Freud’s emphasis on erogenous zones. Erikson identified eight stages, each of which includes a conflict or developmental task. The development of a healthy personality and a sense of competence depend on the successful completion of each task.

Psychosocial Stages of Development

Erikson’s Psychosocial Theory

Now, let’s turn to a less controversial psychodynamic theorist, the father of developmental psychology, Erik Erikson (1902-1994). Erikson was a student of Freud’s and expanded on his theory of psychosexual development by emphasizing the importance of culture in parenting practices and motivations and adding three stages of adult development (Erikson, 1950; 1968).

Background

As an art school dropout with an uncertain future, young Erik Erikson met Freud’s daughter, Anna Freud, while he was tutoring the children of an American couple undergoing psychoanalysis in Vienna. It was Anna Freud who encouraged Erikson to study psychoanalysis. Erikson received his diploma from the Vienna Psychoanalytic Institute in 1933, and as Nazism spread across Europe, he fled the country and immigrated to the United States that same year. Erikson later proposed a psychosocial theory of development, suggesting that an individual’s personality develops throughout the lifespan—a departure from Freud’s view that personality is fixed in early life. In his theory, Erikson emphasized the social relationships that are important at each stage of personality development, in contrast to Freud’s emphasis on erogenous zones. Erikson identified eight stages, each of which includes a conflict or developmental task. The development of a healthy personality and a sense of competence depend on the successful completion of each task.

Erikson believed that we are aware of what motivates us throughout life and that the ego has greater importance in guiding our actions than does the id. We make conscious choices in life, and these choices focus on meeting certain social and cultural needs rather than purely biological ones. Humans are motivated, for instance, by the need to feel that the world is a trustworthy place, that we are capable individuals, that we can make a contribution to society, and that we have lived a meaningful life. These are all psychosocial problems.

Erikson’s theory is based on what he calls the epigenetic principle, encompassing the notion that we develop through an unfolding of our personality in predetermined stages, and that our environment and surrounding culture influence how we progress through these stages. This biological unfolding in relation to our socio-cultural settings is done in stages of psychosocial development, where “progress through each stage is in part determined by our success, or lack of success, in all the previous stages.”[1]

Erikson described eight stages, each with a major psychosocial task to accomplish or crisis to overcome. Erikson believed that our personality continues to take shape throughout our life span as we face these challenges. We will discuss each of these stages in greater detail when we discuss each of these life stages throughout the course. Here is an overview of each stage:

- Trust vs. Mistrust (Hope)—From birth to 12 months of age, infants must learn that adults can be trusted. This occurs when adults meet a child’s basic needs for survival. Infants are dependent upon their caregivers, so caregivers who are responsive and sensitive to their infant’s needs help their baby to develop a sense of trust; their baby will see the world as a safe, predictable place. Unresponsive caregivers who do not meet their baby’s needs can engender feelings of anxiety, fear, and mistrust; their baby may see the world as unpredictable. If infants are treated cruelly or their needs are not met appropriately, they will likely grow up with a sense of mistrust for people in the world.

- Autonomy vs. Shame (Will)—As toddlers (ages 1–3 years) begin to explore their world, they learn that they can control their actions and act on their environment to get results. They begin to show clear preferences for certain elements of the environment, such as food, toys, and clothing. A toddler’s main task is to resolve the issue of autonomy vs. shame and doubt by working to establish independence. This is the “me do it” stage. For example, we might observe a budding sense of autonomy in a 2-year-old child who wants to choose her clothes and dress herself. Although her outfits might not be appropriate for the situation, her input in such basic decisions has an effect on her sense of independence. If denied the opportunity to act on her environment, she may begin to doubt her abilities, which could lead to low self-esteem and feelings of shame.

- Initiative vs. Guilt (Purpose)—Once children reach the preschool stage (ages 3–6 years), they are capable of initiating activities and asserting control over their world through social interactions and play. According to Erikson, preschool children must resolve the task of initiative vs. guilt. By learning to plan and achieve goals while interacting with others, preschool children can master this task. Initiative, a sense of ambition and responsibility, occurs when parents allow a child to explore within limits and then support the child’s choice. These children will develop self-confidence and feel a sense of purpose. Those who are unsuccessful at this stage—with their initiative misfiring or stifled by over-controlling parents—may develop feelings of guilt.

- Industry vs. Inferiority (Competence)—During the elementary school stage (ages 7–12), children face the task of industry vs. inferiority. Children begin to compare themselves with their peers to see how they measure up. They either develop a sense of pride and accomplishment in their schoolwork, sports, social activities, and family life, or they feel inferior and inadequate because they feel that they don’t measure up. If children do not learn to get along with others or have negative experiences at home or with peers, an inferiority complex might develop into adolescence and adulthood.

- Identity vs. Role Confusion (Fidelity)—In adolescence (ages 12–18), children face the task of identity vs. role confusion. According to Erikson, an adolescent’s main task is developing a sense of self. Adolescents struggle with questions such as “Who am I?” and “What do I want to do with my life?” Along the way, most adolescents try on many different selves to see which ones fit; they explore various roles and ideas, set goals, and attempt to discover their adult selves. Adolescents who are successful at this stage have a strong sense of identity and are able to remain true to their beliefs and values in the face of problems and other people’s perspectives. When adolescents are apathetic, do not make a conscious search for identity, or are pressured to conform to their parents’ ideas for the future, they may develop a weak sense of self and experience role confusion. They will be unsure of their identity and confused about the future. Teenagers who struggle to adopt a positive role will likely struggle to find themselves as adults.

- Intimacy vs. Isolation (Love)—People in early adulthood (20s through early 40s) are concerned with intimacy vs. isolation. After we have developed a sense of self in adolescence, we are ready to share our life with others. However, if other stages have not been successfully resolved, young adults may have trouble developing and maintaining successful relationships with others. Erikson said that we must have a strong sense of self before we can develop successful intimate relationships. Adults who do not develop a positive self-concept in adolescence may experience feelings of loneliness and emotional isolation.

- Generativity vs. Stagnation (Care)—When people reach their 40s, they enter the time known as middle adulthood, which extends to the mid-60s. The social task of middle adulthood is generativity vs. stagnation. Generativity involves finding your life’s work and contributing to the development of others through activities such as volunteering, mentoring, and raising children. During this stage, middle-aged adults begin contributing to the next generation, often through caring for others; they also engage in meaningful and productive work which contributes positively to society. Those who do not master this task may experience stagnation and feel as though they are not leaving a mark on the world in a meaningful way; they may have little connection with others and little interest in productivity and self-improvement.

- Integrity vs. Despair (Wisdom)—From the mid-60s to the end of life, we are in the period of development known as late adulthood. Erikson’s task at this stage is called integrity vs. despair. He said that people in late adulthood reflect on their lives and feel either a sense of satisfaction or a sense of failure. People who feel proud of their accomplishments feel a sense of integrity, and they can look back on their lives with few regrets. However, people who are not successful at this stage may feel as if their life has been wasted. They focus on what “would have,” “should have,” and “could have” been. They may face the end of their lives with feelings of bitterness, depression, and despair.

| Stage | Approximate Age (years) | Virtue: Developmental Task | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0–1 | Hope: Trust vs. Mistrust | Trust (or mistrust) that basic needs, such as nourishment and affection, will be met |

| 2 | 1–3 | Will: Autonomy vs. Shame | Sense of independence in many tasks develops |

| 3 | 3–6 | Purpose: Initiative vs. Guilt | Take initiative on some activities, may develop guilt when success not met or boundaries overstepped |

| 4 | 7–11 | Competence: Industry vs. Inferiority | Develop self-confidence in abilities when competent or sense of inferiority when not |

| 5 | 12–18 | Fidelity: Identity vs. Role Confusion | Experiment with and develop identity and roles |

| 6 | 19–39 | Love: Intimacy vs. Isolation | Establish intimacy and relationships with others |

| 7 | 40–64 | Care: Generativity vs. Stagnation |

Contribute to society and be part of a family |

| 8 | 65+ | Wisdom: Integrity vs. Despair | Assess and make sense of life and meaning of contributions |

Strengths and weaknesses of Erikson’s theory

Erikson’s eight stages form a foundation for discussions on emotional and social development during the lifespan. Keep in mind, however, that these stages or crises can occur more than once or at different times of life. For instance, a person may struggle with a lack of trust beyond infancy. Erikson’s theory has been criticized for focusing so heavily on stages and assuming that the completion of one stage is a prerequisite for the next crisis of development. His theory also focuses on the social expectations that are found in certain cultures, but not in all. For instance, the idea that adolescence is a time of searching for identity might translate well in the middle-class culture of the United States, but not as well in cultures where the transition into adulthood coincides with puberty through rites of passage and where adult roles offer fewer choices.

By and large, Erikson’s view that development continues throughout the lifespan is very significant and has received great recognition. However, like Freud’s theory, it has been criticized for focusing on more men than women and also for its vagueness, making it difficult to test rigorously.

Behaviorism’s Perspective

Classical Conditioning

John B. Watson

The 20th century marked the formation of qualitative distinctions between children and adults. When John Watson wrote the book Psychological Care of Infant and Child in 1928, he sought to add clarification surrounding behaviorists’ views on child care and development. Watson was the founder of the field of behaviorism, which emphasized the role of nurture, or the environment, in human development. He believed, based on Locke’s environmentalist position, that human behavior can be understood in terms of experiences and learning. He believed that all behaviors are learned, or conditioned, as evidenced by his famous “Little Albert” study, in which he conditioned an infant to fear a white rat. In Watson’s book on the care of the infant and child, Watson explained that children should be treated as young adults—with respect, but also without emotional attachment. In the book, he warned against the inevitable dangers of a mother providing too much love and affection. Watson explained that love, along with everything else as the behaviorist saw the world, is conditioned. Watson supported his warnings by mentioning invalidism, saying that society does not overly comfort children as they become young adults in the real world, so parents should not set up these unrealistic expectations. His book (obviously) became highly criticized but was still influential in promoting more research into early childhood behavior and development.

Operant Conditioning

B.F. Skinner

Now we turn to the second type of associative learning, operant conditioning. In operant conditioning, organisms learn to associate a behavior and its consequence (Table 1). A pleasant consequence makes that behavior more likely to be repeated in the future. For example, Spirit, a dolphin at the National Aquarium in Baltimore, does a flip in the air when her trainer blows a whistle. The consequence is that she gets a fish.

Psychologist B. F. Skinner saw that classical conditioning is limited to existing behaviors that are reflexively elicited, and it doesn’t account for new behaviors such as riding a bike. He proposed a theory about how such behaviors come about. Skinner believed that behavior is motivated by the consequences we receive for the behavior: the reinforcements and punishments. His idea that learning is the result of consequences is based on the law of effect, which was first proposed by psychologist Edward Thorndike. According to the law of effect, behaviors that are followed by consequences that are satisfying to the organism are more likely to be repeated, and behaviors that are followed by unpleasant consequences are less likely to be repeated (Thorndike, 1911). Essentially, if an organism does something that brings about a desired result, the organism is more likely to do it again. If an organism does something that does not bring about a desired result, the organism is less likely to do it again. An example of the law of effect is in employment. One of the reasons (and often the main reason) we show up for work is because we get paid to do so. If we stop getting paid, we will likely stop showing up—even if we love our job.

Skinner believed that we learn best when our actions are reinforced. For example, a child who cleans his room and is reinforced (rewarded) with a big hug and words of praise is more likely to clean it again than a child whose deed goes unnoticed. Skinner believed that almost anything could be reinforcing. A reinforcer is anything following a behavior that makes it more likely to occur again. It can be something intrinsically rewarding (called intrinsic or primary reinforcers), such as food or praise, or it can be something that is rewarding because it can be exchanged for what one really wants (such as receiving money and using it to buy a cookie). Such reinforcers are referred to as secondary reinforcers.

Cognitive Perspective

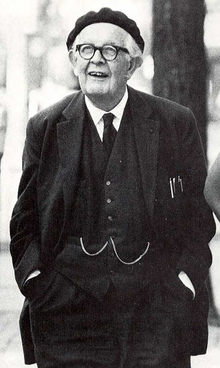

Jean Piaget

Jean Piaget (1896-1980) is considered one of the most influential psychologists of the twentieth century, and his stage theory of cognitive development revolutionized our view of children’s thinking and learning. His work inspired more research than any other theorist, and many of his concepts are still foundational to developmental psychology. His interest lay in children’s knowledge, their thinking, and the qualitative differences in their thinking as it develops. Although he called his field “genetic epistemology,” stressing the role of biological determinism, he also assigned great importance to experience. In his view, children “construct” their knowledge through processes of “assimilation,” in which they evaluate and try to understand new information, based on their existing knowledge of the world, and “accommodation,” in which they expand and modify their cognitive structures based on new experiences.

Modern developmental psychology generally focuses on how and why certain modifications throughout an individual’s life-cycle (cognitive, social, intellectual, personality) and human growth change over time. There are many theorists that have made, and continue to make, a profound contribution to this area of psychology, amongst whom is Erik Erikson who developed a model of eight stages of psychological development. He believed that humans developed in stages throughout their lifetimes and this would affect their behaviors. In this module, we’ll examine some of these major theories and contributions made by prominent psychologists.

The Humanistic Perspective

LEARNING OUTCOMES

- Describe the major concepts of humanistic theory (unconditional positive regard, the good life), as developed by Carl Rogers

- Explain Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

The Humanistic Perspective: A Focus on Uniquely Human Qualities

The humanistic perspective rose to prominence in the mid-20th century in response to psychoanalytic theory and behaviorism; this perspective focuses on how healthy people develop and emphasizes an individual’s inherent drive towards self-actualization and creativity. Humanism emphasizes human potential and an individual’s ability to change, and rejects the idea of biological determinism. Humanistic work and research are sometimes criticized for being qualitative (not measurement-based), but there exist a number of quantitative research strains within humanistic psychology, including research on happiness, self-concept, meditation, and the outcomes of humanistic psychotherapy (Friedman, 2008).

Carl Rogers and Humanism

One pioneering humanistic theorist was Carl Rogers. He was an influential humanistic psychologist who developed a personality theory that emphasized the importance of the self-actualizing tendency in shaping human personalities. He also believed that humans are constantly reacting to stimuli with their subjective reality (phenomenal field), which changes continuously. Over time, a person develops a self-concept based on the feedback from this field of reality.

Figure 1. The phenomenal field refers to a person’s subjective reality, which includes external objects and people as well as internal thoughts and emotions. The person’s motivations and environments both act on their phenomenal field.

One of Rogers’s main ideas about personality regards self-concept, our thoughts and feelings about ourselves. How would you respond to the question, “Who am I?” Your answer can show how you see yourself. If your response is primarily positive, then you tend to feel good about who you are, and you probably see the world as a safe and positive place. If your response is mainly negative, then you may feel unhappy with who you are. Rogers further divided the self into two categories: the ideal self and the real self. The ideal self is the person that you would like to be; the real self is the person you actually are. Rogers focused on the idea that we need to achieve consistency between these two selves.

Unconditional Positive Regard

Human beings develop an ideal self and a real self, based on the conditional status of positive regard. How closely one’s real self matches up with their ideal self is called congruence. We experience congruence when our thoughts about our real self and ideal self are very similar—in other words when our self-concept is accurate. High congruence leads to a greater sense of self-worth and a healthy, productive life. Conversely, when there is a great discrepancy between our ideal and actual selves, we experience a state Rogers called incongruence, which can lead to maladjustment.

According to Rogers, parents can help their children achieve their ideal self by giving them unconditional positive regard, or unconditional love. In the development of self-concept, positive regard is key. Unconditional positive regard is an environment that is free of preconceived notions of value. Conditional positive regard is full of conditions of worth that must be achieved to be considered successful. Rogers (1980) explained it this way: “As persons are accepted and prized, they tend to develop a more caring attitude towards themselves” (p. 116).

The Good Life

Rogers described life in terms of principles rather than stages of development. These principles exist in fluid processes rather than static states. He claimed that a fully functioning person would continually aim to fulfill their potential in each of these processes, achieving what he called “the good life.“ These people would allow personality and self-concept to emanate from experience. He found that fully functioning individuals had several traits or tendencies in common:

- A growing openness to experience–they move away from defensiveness.

- An increasingly existential lifestyle–living each moment fully, rather than distorting the moment to fit personality or self-concept.

- Increasing organismic trust–they trust their own judgment and their ability to choose behavior that is appropriate for each moment.

- Freedom of choice–they are not restricted by incongruence and are able to make a wide range of choices more fluently. They believe that they play a role in determining their own behavior and so feel responsible for their own behavior.

- Higher levels of creativity–they will be more creative in the way they adapt to their own circumstances without feeling a need to conform.

- Reliability and constructiveness–they can be trusted to act constructively. Even aggressive needs will be matched and balanced by intrinsic goodness in congruent individuals.

- A rich full life–they will experience joy and pain, love and heartbreak, fear and courage more intensely.

TRY IT

Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Abraham Maslow (1908–1970) was an American psychologist who is best known for proposing a hierarchy of human needs in motivating behavior. Maslow described a pattern through which human motivations generally move, meaning that in order for motivation to occur at the next level, each level must be satisfied within the individual themselves. These stages include:

- physiological needs: the main physical requirements for human survival, including homeostasis, food, water, sleep, shelter, and sex.

- safety needs: the need for personal, emotional, financial, and physical security. Once a person’s physiological needs are relatively satisfied, their safety needs take precedence and dominate behavior. In the absence of physical safety – due to war, natural disaster, family violence, childhood abuse, institutional racism, etc. – people may (re-)experience post-traumatic stress disorder or transgenerational trauma. In the absence of economic safety – due to an economic crisis and lack of work opportunities – these safety needs manifest themselves in ways such as a preference for job security, grievance procedures for protecting the individual from unilateral authority, savings accounts, insurance policies, disability accommodations, etc. This level is more likely to predominate in children as they generally have a greater need to feel safe.

- love and belonging: the need for friendships, intimacy, and belonging. This need is especially strong in childhood and it can override the need for safety as witnessed in children who cling to abusive parents. Deficiencies within this level of Maslow’s hierarchy – due to hospitalism, neglect, shunning, ostracism, etc. – can adversely affect the individual’s ability to form and maintain emotionally significant relationships in general.

- esteem: the typical human desire to be accepted and valued by others. People often engage in a profession or hobby to gain recognition. Esteem needs are ego needs or status needs. People develop a concern with getting recognition, status, importance, and respect from others. Most humans have a need to feel respected; this includes the need to have self-esteem and self-respect.

- self-actualization: Maslow describes this level as the desire to accomplish everything that one can, to become the most that one can be. Individuals may perceive or focus on this need very specifically. For example, one individual may have a strong desire to become an ideal parent. In another, the desire may be expressed athletically. For others, it may be expressed in paintings, pictures, or inventions. Some examples of this include utilizing abilities and talents, pursuing goals, and seeking happiness.

Furthermore, this theory is a key foundation in understanding how drive and motivation are correlated when discussing human behavior. Each of these individual levels contains a certain amount of internal sensation that must be met in order for an individual to complete their hierarchy. The goal in Maslow’s theory is to attain the fifth level or stage of self-actualization.

Figure 2. Diagram of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is often portrayed in the shape of a pyramid with the largest, most fundamental needs at the bottom and the need for self-actualization and transcendence at the top. In other words, the crux of the theory is that individuals’ most basic needs must be met before they become motivated to achieve higher-level needs.

WATCH IT

Watch as Maslow’s hierarchy of needs comes to life in this quick video.

You can view the transcript for “Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs” here (opens in new window).

TRY IT#

GLOSSARY

- congruence:

- an instance or point of agreement or correspondence between the ideal self and the real self in Rogers’ humanistic personality theory

- humanism:

- a psychological theory that emphasizes an individual’s inherent drive towards self-actualization and contends that people have a natural capacity to make decisions about their lives and control their own behavior

- Maslow’s hierarchy of needs:

- a motivational theory in psychology comprising a five-tier model of human needs, often depicted as hierarchical levels within a pyramid. Needs lower down in the hierarchy must be satisfied before individuals are motivated to attend to needs higher up

- phenomenal field:

- our subjective reality, all that we are aware of, including objects and people as well as our behaviors, thoughts, images, and ideas

- self-actualization:

- according to humanistic theory, the realizing of one’s full potential can include creative expression, a quest for spiritual enlightenment, the pursuit of knowledge, or the desire to contribute to society. For Maslow, it is a state of self-fulfillment in which people achieve their highest potential in their own unique way

Evolutionary Perspective

Figure 1. A portrait of Charles Robert Darwin. In the distant future I see open fields for far more important researches. Psychology will be based on a new foundation, that of the necessary acquirement of each mental power and capacity by gradation. — DARWIN, CHARLES (1859). . P. 488 – VIA WIKISOURCE

Evolutionary psychology has its historical roots in Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection. In The Origin of Species, Darwin predicted that psychology would develop an evolutionary basis, and that a process of natural selection creates traits in a species that are adaptive to its environment.

Using Darwin’s arguments, evolutionary approaches claim that one’s genetic inheritance not only determine such physical traits as skin and eye color, but also certain personality traits and social behaviors. For example, some evolutionary developmental psychologists suggest that behavior such as shyness and jealousy may be produced in part by genetic causes, presumably because they helped increase the survival rates of human’s ancient relatives.[1][2][3]

Behavioral Genetics

The evolutionary perspective encompasses one of the fastest-growing areas within the field of lifespan development: behavioral genetics. Behavioral genetics is a field of scientific research that uses genetic methods to investigate the nature and origins of individual differences in behavior and studies the effects of heredity on behavior. Behavioral geneticists strive to understand how we might inherit certain behavioral traits and how the environment influences whether we actually displayed those traits. It also considers how genetic factors may influence psychological disorders such as schizophrenia, depression and substance abuse.[4][5][6]

LINK TO LEARNING

In Stanford, professor and author of Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers, Robert Sapolsky’s Ted Talk, Sapolsky describes how our history and biology influence our behavior. This tour of our individual and collective history provides an enlightening overview of behavioral genetics.