The History of New Mexico

Collapse

Expand

-

Chapter 14: World War II Era: Manhattan Project & Growing Federal Presence in New Mexico

- World War II Era: Manhattan Project & Growing Federal Presence in New Mexico

- World War II

- Manhattan Project

- Site Y

- Testing the Bomb

- Impact on Local Communities

- References & Further Reading

One evening in their home at the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos, then referred to by the codename “Site Y,” Phyllis Fisher jokingly suggested a name to her husband, Leon, for the baby that the couple was expecting. In a playful tone, she quipped that the name “Uranium Fisher” would be perfect. In response, Leon became visibly agitated and yelled at her to never again mention that word. She protested, “I only said ‘Ur-,’” but she was unable to finish the word before he clapped his hand over her mouth.1

Somewhat perplexed by her husband’s response, Phyllis looked up the term “uranium fission” in a dictionary later that evening and learned that it was a process that could potentially produce an extremely powerful explosion. Although she must have had some clues about her husband’s work at Site Y, he and other participants of the Manhattan Project had been prohibited from sharing details—or even cursory information—about their work with anyone, including their spouses.

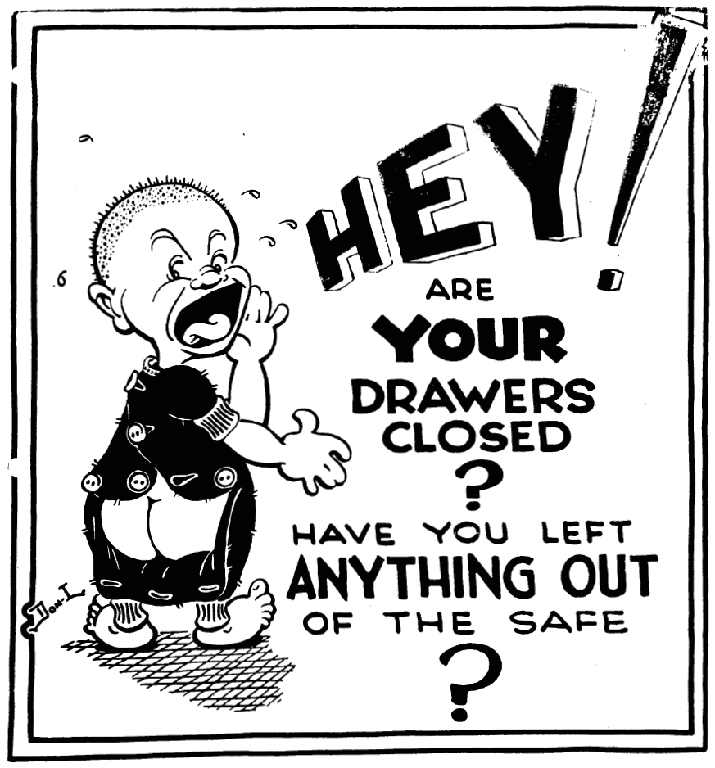

As historian Jon Hunner has explained, life at Site Y was defined by the requirement of secrecy. Scientists and their wives dealt with the nature of their assignment in various ways. Anger, resentment, humor, and defiance were among the responses to the strict censorship that was prevalent in wartime Los Alamos.

Courtesy of Los Alamos National Laboratory

Richard Feynman, a physicist on the project, made a personal crusade out of challenging the censors. When his wife Arline contracted tuberculosis and underwent treatment at an Albuquerque hospital, the couple used code in their letters to one another. Code was strictly forbidden and it occasioned Feynman’s frequent arguments with the censors assigned to the project. Over time, he learned what types of information the censors would allow and he “won bets with fellow workers by phrasing forbidden subjects in such a way that the censors had to allow the offending letter to pass.”2

More typically, secrecy and confinement at Site Y inspired participation in community and social events. Residents organized clubs for hiking, skiing, square dancing, and theater, among other activities. One of the prominent rumors that circulated in Santa Fe was that the facility on the Hill was a hospital for pregnant members of the Women’s Army Corps (WAC). That rumor was likely fueled by the more intimate way in which many couples dealt with the situation at Site Y. Medical facilities were overwhelmed by the high rate of pregnancies and births.

The young children of the physicists, engineers, military personnel, and other project participants made sense of the situation as best as they could. Later in life, Claire Ulam Weiner recalled attending parties as a girl where men huddled in the corners engaged in hushed conversations. She grew up thinking that such behavior was typical of all fathers.

As Hunner points out in his study of family life in Los Alamos, “Children and silence, like secrecy and families, are antithetical.”3 The situation of five-year-old Ellen Wilder Reid underscores the impact of the atmosphere on young children. Not long after their arrival at Site Y, Ellen’s brother accidentally smashed her thumb while they were throwing rocks into a nearby stream. Due to a lack of housing, her family had been living in a tent just outside the facility’s gates.

Courtesy of Los Alamos National Laboratory

When her father attempted to rush her to the hospital inside the gates, the sentry refused to allow her entry because she did not possess the proper security clearance. Only after an argument with the guard and a phone call to officials inside the facility were they permitted to enter. Based on the experience, young Ellen learned that something intensely secret was taking place inside the fences. As she attempted to figure out what the secret was, she “saw only ugly buildings” at Site Y.4 Her efforts to make sense of the situation led her to believe that ducks on Ashley Pond were the reason for the secrecy. After all, the ducks seemed much more interesting and worthy of protection than the buildings by the reasoning of a five-year-old.

Courtesy of Los Alamos National Laboratory

Secrecy and enforced silence shaped the community at Los Alamos. Such measures were intended to prevent the Axis Powers from gaining access to nuclear technology and to prevent the proliferation of atomic weaponry across the globe. Yet such was not to be the case. Years after the war had ended, director J. Robert Oppenheimer concluded that secrecy during the Manhattan Project was part of the problem. He felt that history might have played out differently “if we had acted wisely” and not been swayed by “the delusions of the effect of secrecy.”5

Immediately after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the laboratory and community of Los Alamos was thrust into the limelight. The following December, to celebrate, physicists and their families traveled a short distance to San Ildefonso Pueblo to witness the Pueblo’s traditional deer dance, an annual occasion. Unlike most deer dances, this one combined square dancing with traditional Pueblo music, dances, and foods. In the midst of the festivities, the governor of the Pueblo shouted “this is the atomic age, this is the atomic age.”6

Beyond wartime tourism and the postwar celebration, however, residents of the atomic community of Los Alamos wished to maintain separation from the surrounding area. Although many of the fences around the nuclear facilities at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and Hanford, Washington, came down within a few years of the war’s end, residents of Los Alamos demanded that the fences be maintained, and they remained in place until 1957.

The people of San Ildefonso and Santa Clara Pueblos had little choice in the initial decision to locate the secret nuclear facility in the isolation of northern New Mexico. The federal government, upon recommendation of Oppenheimer and General Leslie R. Groves, appropriated about forty-three square miles of lands that had belonged to San Ildefonso, Santa Clara, and the Spanish land grant of Ramón Vigil. By some estimates, there are at least 2,400 different sites in the surrounding canyons and forests that have been contaminated since Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) opened. Radioactive pollutants, such as strontium-90, uranium, plutonium, and tritium, as well as industrial waste, including lead and mercury, were emitted into local landscapes.7

Without their knowledge, much less their permission, the people at San Ildefonso and Santa Clara were subjected to radioactive fallout from the initial experiments at Site Y, as well as later research at LANL. Despite the shared celebrations in 1945, officials from Los Alamos did not meet formally with representatives of any of the local Pueblos until the 1990s to discuss the impact of the labs on tribal lands. Due to proximity, however, much of the environmental effects of work at the labs has been felt by the Pueblos. A zone called Area G, for example, borders San Ildefonso lands and about 380,000 cubic-feet of radioactive waste has been located there since the early 1970s.

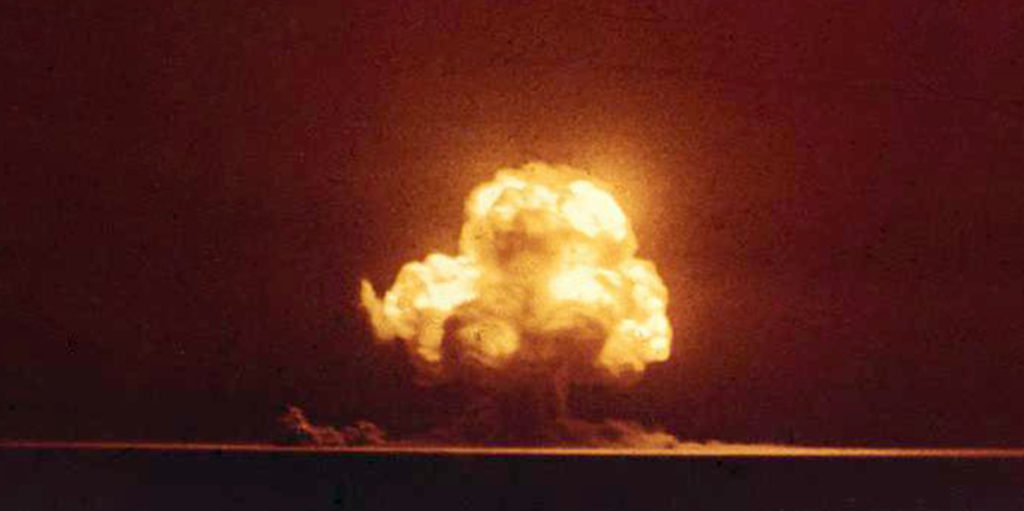

The work at Los Alamos altered the trajectory of the entire world. Following the development of atomic technology, nature itself was transformed and global politics shifted. Radioactive elements, such as tritium and strontium-90, can be found in trace amounts in landscapes and wildlife species around the world. Such was not the case prior to 1945.

Los Alamos National Laboratory and Sandia National Laboratory formed an integral part of New Mexico’s economy, a reality that continues today. Both facilities expanded the role of the federal government in the state and boosted its economic growth. At the same time, however, LANL and Sandia provide examples of continued colonial relationships between New Mexico’s peoples and the U.S. central government. Los Alamos was imposed on the state as a necessity of the race to victory in World War II.

Despite the prosperity and social stability evident in majority-Anglo Los Alamos, neighboring nuevomexicano communities have not shared in the wealth. Poverty continues to plague the northern part of the state. Various observers suggest that nuevomexicano and Pueblo cultural traditions are to blame. However, Father Casimiro Roca, priest at the Santuario de Chimayó since 1959, explained the situation in a different way: “People are poor here not because they are trying to hold onto the past but because they are paid too little, receive a poor education, and have few options.”8 Military spending during World War II ended the Great Depression, but the rise of the military-industrial complex in New Mexico has done little to alleviate the economic and social trends that had been current since the decade of the 1930s.