LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- Identify the subject and verb in a sentence.

- Recognize different sentence styles.

- Understand different sentence constructions.

The foundation of all good sentences is a strong subject and verb.

Building Sentences

Like an architect can create walls, bridges, arches, and roads with the same bricks, you can create sentences that serve varying functions using the building blocks of words. Just as an architect plans different features in an edifice to create a strong and beautiful building, a writer must use a variety of sentence structures to capture readers’ interest. And like a builder must begin with a solid foundation, your sentences need to begin with clear, strong words. The more practice you have putting sentences together, the more interesting your writing will become.

First, let’s work on clarity through specificity. “Le bon mot,” or “the right word,” is key, and it begins with nouns and verbs.

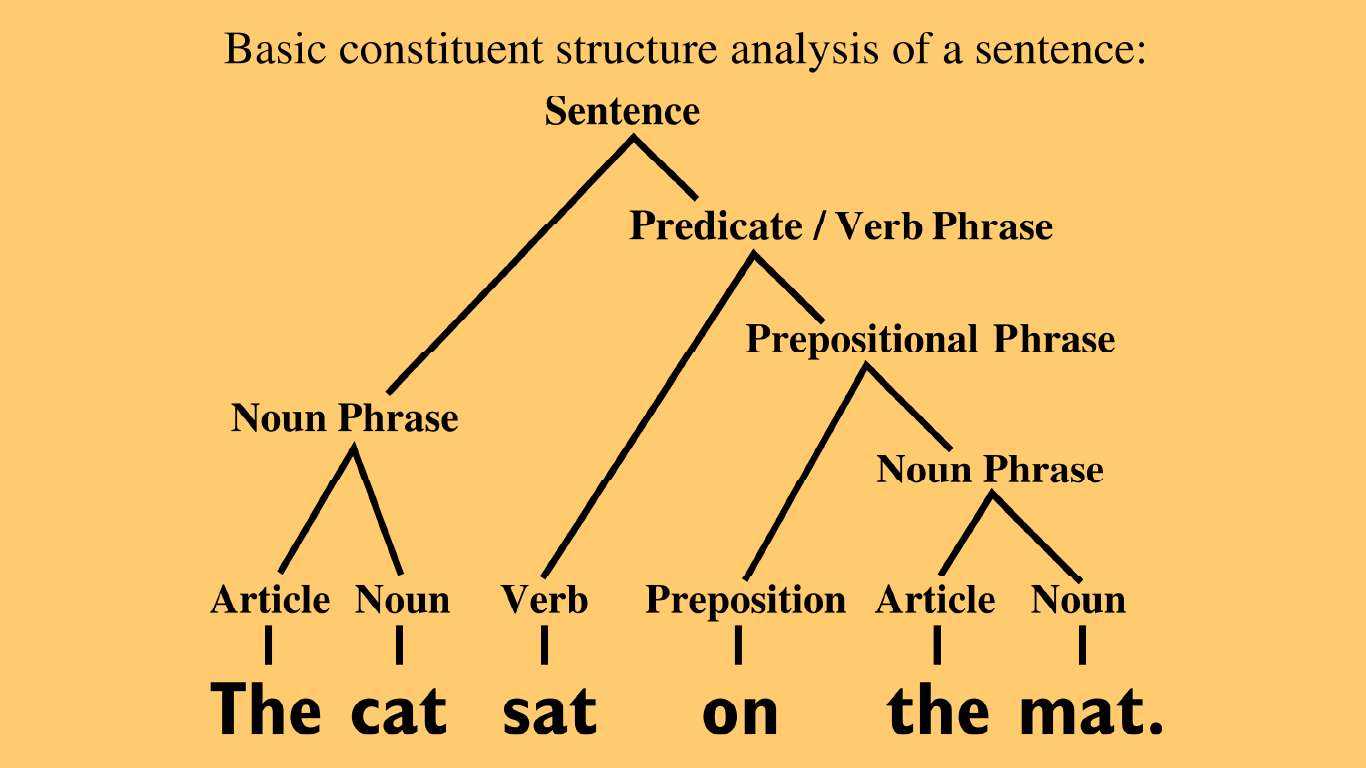

Subjects and Verbs

Despite contrary trends in the popular press, formal writing still requires of a sentence both a subject and a verb.

- Jesus wept.

- The schooner capsized.

- She died.

- They won.

- Paris seduces.

- It is.

- These are all sentences.

You already know that you need a subject and a verb to create a sentence. What you may not know is that these are the two most important parts of a sentence. The more specific the noun, the more your reader will be able to picture what it is you’re talking about (“schooner” is more specific than “boat,” “Paris” more specific than “France”). Pronouns work well when the antecedent is clear. While repeating a noun can get ponderous, unidentifiable pronouns confuse the reader.

Verbs, too, captivate when they’re exact. Adjectives and adverbs, it’s said, were invented for those who don’t know enough verbs. Take the sentence “Paris seduces,” for example. You could just as easily say, “Paris is seductive,” but the use of the verb “to be” makes the sentence less active and alive.

From this solid base, you can begin adding your objects and clauses to create more complex sentences.

Classifying Sentences by Structure

Sentences can be classified by their structure or by their purpose. You’ll want to keep both in mind as you write.

Structural classifications for sentences include simple sentences, compound sentences, complex sentences, and compound-complex sentences.

You’ll want to have a mix of sentence types in almost anything you write, as varying length and complexity keeps the reader’s attention. The sing-song nature of same-length sentences seems to trigger a lullaby response in our brains, and our eyes can’t help but droop. In addition to the rhythm of it, though, you’ll communicate more substance with varying sentence lengths.

Simple Sentences

- A simple sentence consists of a single independent clause with no subordinate clauses. For example:

- I love chocolate cake with rainbow sprinkles.

- “Without love, life would be empty.” This sentence contains a subject (life), a verb (would be) and two types of modifiers (without love and empty).

Simple sentences are often used to introduce a topic or present a new thought in an argument —for example, “Juries are charged with rendering impartial verdicts,” or “Income taxes are high in Scandinavian countries.” You may notice that with both these examples, the reader is likely to start formulating objections or opinions about the topic right away. As a writer, you can use simple sentences in this way. Writing a simple sentence to begin a paragraph can have the reader making your argument for you before you’ve even begun to state your point.

Compound Sentences

A compound sentence consists of multiple independent clauses with no subordinate clauses. These clauses are joined together using conjunctions, punctuation, or both. For example:

- I love chocolate cake with rainbow sprinkles, and I eat it all the time for breakfast.

- Together we stand; united we fall.

You can feel the power of that second example. Using a semicolon without a conjunction adds drama to a compound sentence, especially when you’re comparing two concepts and the independent clauses are of approximately equal length.

Compound sentences connected with “and” make connections between ideas. The sentence, “It’s clear that we do have the means to end poverty worldwide, and every moment we hesitate means one more child dies of hunger,” exposes the connection between having the means to end poverty and the consequences of not employing those means.

Using “but” takes exception with the first clause: “Eileen treats her boyfriend like a servant, but he isn’t going to stand for that for long.”

You can use a semicolon to show a relationship between clauses: “Bats are nocturnal; they are active only at night.”

“However,” “nonetheless,” and “still” are often used as qualifiers between independent clauses. For example, “There were no luxuries like pillows in the convent; however, some residents did find ways to create comfort.”

You can show causation using “therefore” and “thus,”—for example, “The countries that are least committed to reducing fossil fuel use are the largest; therefore, we are unlikely to stave the crisis.”

You can show emphasis using connectors like, “moreover,” and “furthermore.” “Hilda has not done her chores in a week; moreover, she has been eating twice her share at dinner.”

Complex Sentences

A complex sentence consists of at least one independent clause and one subordinate clause. For example:

- “While I love him dearly, I will rehome my pterodactyl for the sake of the community.”

- “Those who eat chocolate cake will be happy.” In this case, the subordinate clause, “who eat chocolate cake” is in the middle of the sentence.

“If-then” sentences are complex sentences: “If Americans don’t change their dietary habits, the medical system will soon be bankrupt.” (Notice that the “then” is implied.)

Other connectors for complex sentences include “because,” “although,” “so that,” “since.”

- “I have had strong convictions since I was old enough to reason.”

Compound-Complex Sentences

A compound-complex sentence (or complex-compound sentence) consists of multiple independent clauses, at least one of which has at least one subordinate clause. For example:

- “I love my pet pterodactyl, but since he’s been eating neighborhood cats, I will donate him to the city zoo.” Here, the subordinate clause is, “since he’s been eating neighborhood cats.”

- “Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you what you are.” This sentence contains two independent clauses (one before and one after the comma), and each independent clause contains a subordinate clause (“what you eat” and “what you are”).

There are countless variations of compound-complex sentences, and while they can be complicated, they are often necessary in order to make complete connections between ideas. Don’t make the mistake, though, of using them unnecessarily. Break thoughts into new sentences when you can. When you do use one, try to insert a simple sentence after it. Your reader may need a rest.

Selecting Sentence Construction

- North Americans eat a lot of fast food. They also have a high rate of disease.

- North Americans eat a lot of fast food, and they have a high rate of disease.

- If North Americans continue to eat a lot of fast food, they will continue to have a high rate of disease.

- If North Americans, who eat a lot of fast food, continue to do so, they will likely continue to have a high rate of disease, as proper nutrition is vital to immune function.

In looking at the various sentence forms above, you can see that each sentence gives you a different feel. Can you see how each might be appropriate in different contexts? The simple sentences might work in an introduction to begin to draw the parallel. The compound sentence makes the connection clear. The complex sentence sounds more like a lesson in its “if-then” format, and the compound-complex sentence packs all the information into one conclusive sentence. Which of these sounds most convincing as an argument? Which allows you to draw your own conclusion ?

Classifying Sentences by Purpose

English sentences can also be classified based on their purpose: declarations, interrogatives, exclamations, and imperatives. When you’re composing a paper, you’ll want to clarify the purpose of your sentences to be sure you’re selecting the appropriate form.

Declarations

A declarative sentence, or declaration, is the most common type of sentence. It makes a statement. For example:

- “Most Americans must work to survive.”

- “I love watching the parrots migrate.”

Because you’ll be relying on statements most of the time, you’ll want to vary the structure of your declarative sentences, using the forms above, to be sure your paragraphs don’t feel plodding. One declaration after the next can lull the reader into complacency (or, worse, sleep).

Interrogatives

An interrogative sentence, or question, is commonly used to request information. For example:

- “Do you know what it’s like to have to go to work to be able to eat?”

- “Why has the sky suddenly turned green?”

While you don’t want to overuse the interrogative in an essay, it does serve to wake the reader up a bit. You’re asking the reader to find the answer within him- or herself, rather than simply digesting fact after fact. Helping the reader formulate questions about the topic early can engage readers by accessing their curiosity.

Exclamations

An exclamatory sentence, or exclamation, is a more emphatic form of statement that expresses emotion. For example:

- I have to go to work now!

- Get away from me!

“Show some restraint!” is the general guideline for using exclamations in a paper. And yet, there are times when it won’t seem amateurish or overly hard-hitting. When you’re exposing a contradiction in your opposition’s views, for example, or an inconsistency between views and behaviors, you can signal the importance of this diversion with an exclamation. Recognize, though, that using exclamations only sparingly will bolster your credibility. Like the boy who cried wolf, if you get a reputation for yelling all the time, people will begin to ignore you, even when it really matters.

Imperatives

An imperative sentence tells someone to do something (and may be considered both imperative and exclamatory). This may be in the form of a request, a suggestion, or a demand, and the intended audience is the reader.

- Go to work.

- Trust me!

Imperatives can be effective in making an argument. You can introduce evidence with an imperative (e.g., “Consider the current immigrant crisis in Europe”). You can use an imperative to transition from a counter-argument: “Don’t be fooled by this faulty logic.” You might include an imperative in your conclusion, if you’re including a call to action: “Act now to end human trafficking.”

Checking for Appropriate Sentence Structure and Purpose

In the revision stage of writing, make sure to make a pass over the paper with an eye toward sentence construction. Are there too many interrogatives or exclamations? Does the prose sound convoluted because I use too many compound-complex sentences?

Do I sound condescending because I’m using too many simple sentences? Do the connectors I’m using fit with this particular sentence?

Enjoy constructing your argument using the forms sentences can take. Designing a paper using your skill with sentence structure can feel thoroughly satisfying.

Introduction to Inflection

In the context of grammar, inflection is altering a word to change its form, usually by adding letters.

In English grammar, “inflection” is the broad umbrella term for changing a word to suit its grammatical context. You’ve probably never heard this word before, but you actually do it all the time without even thinking about it. For example, you know to say “Call me tomorrow” instead of “Call I tomorrow”; you’ve changed the noun “I” to fit the context (i.e., so it can be used as a direct object instead of a subject).

A word you might have heard before, especially if you’ve taken a foreign language like Spanish, is “ conjugation.” Conjugation is the specific type of inflection that has to do with verbs. For example, you change a verb based on who is performing the verb: you would say “You call me,” but “She calls me.” Again, you know to do this automatically.

Nouns and Pronouns

We often need to change nouns based on grammatical context. For example, if you change from singular to plural (e.g., from “cat” to “cats,” or from “syllabus” to “syllabi”), you’re “inflecting” the noun. Similarly, if you’re changing the pronoun “I” to “me,” or “she” to “her,” the person you’re referring to isn’t changing, but the word you use does, because of context. “She calls I” is incorrect, as is “Her calls me”; you know to instead say “She calls me.”

Verbs

To recap, “conjugation” refers to changing a verb to suit its grammatical context. This can mean changing the verb based on who is performing the verb (e.g., “you read,” but “she reads”) or based on the time the action is occurring, also known as the verb’s “tense” (e.g., “you walk” for the present, and “you walked” for the past).

Adjectives

You also might need to change some adjectives based on the grammatical context of the rest of your sentence. For example, if you’re trying to compare how sunny today’s weather is to yesterday’s weather, you would change the adjective “sunny” to “sunnier”: “Today is sunnier than yesterday.”

Adverbs

Inflecting adverbs is very similar to how you change adjectives. For example, if you want to compare how quickly two students are learning math, you would change the adverb “easily” to “more easily”: “Huck is learning his fractions much more easily than Tom is.”

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Points

- In English grammar, ” inflection ” refers to changing a word to suit its grammatical context (e.g., making a noun plural when you’re talking about more than one, making a verb past tense when you’re talking about something that has already happened).

- In English, there are many rules that tell you how to change words to suit context, but there are also quite a few exceptions that you’ll just have to memorize.

- Pronouns and nouns change form depending on whether they are the subject (i.e., the actor) or the direct or indirect object (i.e., the thing being acted upon) of a sentence.

Key Terms

- conjugation: The creation of derived forms of a verb from its principal parts by inflection.

- declension: The inflection of nouns, pronouns, articles, and adjectives.

- inflection: In the grammatical sense, modifying a word, usually by adding letters, to create a different form of that word.

Grammar Basics Key Takeaways

Key Points

- To create a strong sentence, begin with a specific subject and a strong verb.

- Sentences can be classified by their structure or by their purpose.

- Structural classifications for sentences include: simple sentences, compound sentences, complex sentences, and compound-complex sentences.

- Particular connectors are used to impart particular meanings in compound and complex sentences.

- Classification categories for sentences by purpose include declarations, interrogatives, exclamations, and imperatives.

- In the revision stage of writing, it’s useful to go over the paper with an eye toward the appropriateness and variety of sentence construction.

Key Terms

- simple sentences: A single independent clause with no subordinate clauses.

- complex sentence: At least one independent clause and one subordinate clause.

- compound-complex sentence: Multiple independent clauses, at least one of which has at least one subordinate clause.

- declarative sentence: A statement or declaration about something.

- exclamatory sentence: An emphatic form of statement that expresses emotion.

- imperative sentence: A statement that tells the reader, in the form of a request, suggestion, or demand, to do something.

- compound sentence: Multiple independent clauses with no subordinate clauses.

- interrogative sentence: Also called a question, it is commonly used to request information.

The Grammar Basics section is adapted from multiple sources:

- “What is Grammar?” from Rhetoric and Composition, used according to Creative Commons CC BY-SA 3.0,

- “21.1 Parts of Speech.” from Appendix A: Writing for Nonnative English Speakers, used according to Creative Commons CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

- And Introduction to English Grammar and Mechanics from Lumen Learning, by Boundless.com, used according to Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0