Learning Objectives

- Review the fundamental principles of [glossary_exclude]causal attribution[/glossary_exclude].

- Compare and contrast the tendency to make person attributions for unusual events, the covariation principle, and Weiner’s model of success and failure.

- Describe some of the factors that lead to inaccuracy in [glossary_exclude]causal attribution[/glossary_exclude].

We have seen that we use personality traits to help us understand and communicate about the people we know. But how do we know what traits people have? People don’t walk around with labels saying “I am generous” or “I am aggressive” on their foreheads. In some cases, we may learn about a person indirectly, for instance, through the comments that other people make about that person. We also use the techniques of person perception to help us learn about people and their traits by observing them and interpreting their behaviors. If Frank hits Joe, we might conclude that Frank is aggressive. If Leslie leaves a big tip for the waitress, we might conclude that Leslie is generous. It seems natural and reasonable to make such inferences because we can assume (often, but not always, correctly) that behavior is caused by personality. It is Frank’s aggressiveness that causes him to hit, and it is Leslie’s generosity that led to her big tip.

Although we can sometimes infer personality by observing behavior, this is not always the case. Remember that behavior is influenced by both our personal characteristics and the social context in which we find ourselves. What this means is that the behavior we observe other people engaging in might not always be that reflective of their personality—the behavior might have been caused by the situation rather than by underlying person characteristics. Perhaps Frank hit Joe not because he is really an aggressive person but because Joe insulted or provoked him first. And perhaps Leslie left a big tip in order to impress her friends rather than because she is truly generous.

Because behavior is determined by both the person and the situation, we must attempt to determine which of these two causes mainly determined the behavior. The process of trying to determine the causes of people’s behavior is known as causal attribution (Heider, 1958). Because we cannot see personality, we must work to infer it. When a couple we know breaks up, despite what seemed to be a match made in heaven, we are naturally curious. What could have caused the breakup? Was it something one of them said or did? Or perhaps stress from financial hardship was the culprit?

Making a causal attribution is a bit like conducting a social psychology experiment. We carefully observe the people we are interested in, and we note how they behave in different social situations. After we have made our observations, we draw our conclusions. We make a personal (or internal or dispositional) attribution when we decide that the behavior was caused primarily by the person. A personal attribution might be something like “I think they broke up because Sarah was not committed to the relationship.” At other times, we may determine that the behavior was caused primarily by the situation—we call this making a situational (or external) attribution. A situational attribution might be something like “I think they broke up because they were under such financial stress.” At yet other times, we may decide that the behavior was caused by both the person and the situation.

Attributions for Success and Failure

Still another time when we may use our powers of causal attribution to help us determine the causes of events is when we attempt to determine why we or others have succeeded or failed at a task. Think back for a moment to a test that you took, or perhaps about another task that you performed, and consider why you did either well or poorly on it. Then see if your thoughts reflect what Bernard Weiner (1985) considered to be the important factors in this regard.

Weiner was interested in how we determine the causes of success or failure because he felt that this information was particularly important for us: Accurately determining why we have succeeded or failed will help us see which tasks we are at good at already and which we need to work on in order to improve. Weiner also proposed that we make these determinations by engaging in causal attribution and that the outcomes of our decision-making process were made either to the person (“I succeeded/failed because of my own person characteristics”) or to the situation (“I succeeded/failed because of something about the situation”).

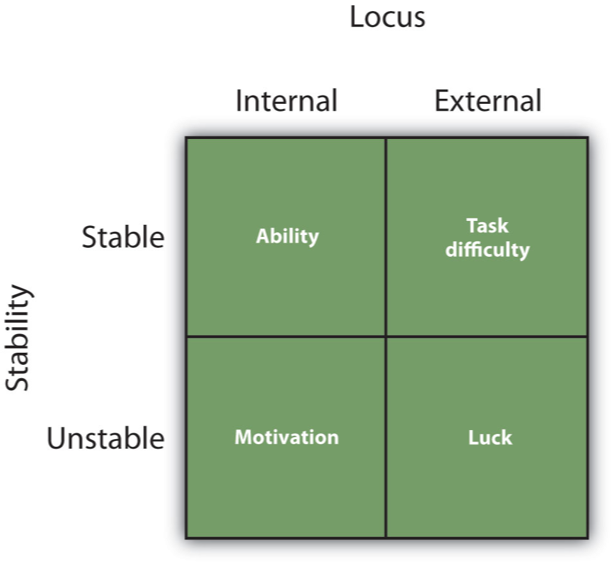

Weiner’s analysis is shown in Figure 4.5 “Attributions for Success and Failure”. According to Weiner, success or failure can be seen as coming from personal causes (ability or motivation) or from situational causes (luck or task difficulty). However, he also argued that those personal and situational causes could be either stable (less likely to change over time) or unstable (more likely to change over time).

If you did well on a test because you are really smart, then this is a personal and stable attribution of ability. It’s clearly something that is caused by you personally, and it is also a stable cause—you are smart today, and you’ll probably be smart in the future. However, if you succeeded more because you studied hard, then this is a success due to motivation. It is again personal or internal (you studied), but it is also unstable (although you studied really hard for this test, you might not work so hard for the next one). Weiner considered task difficulty to be a situational cause—you may have succeeded on the test because it was easy, and he assumed that the next test would probably be easy for you too (i.e., that the task, whatever it is, is always either hard or easy). Finally, Weiner considered success due to luck (you just guessed a lot of the answers correctly) to be a situational cause, but one that was more unstable than task difficulty.

It turns out that although Weiner’s attributions do not always fit perfectly (e.g., task difficulty may sometimes change over time and thus be at least somewhat unstable), the four types of information pretty well capture the types of attributions that people make for success and failure.

Overemphasizing the Role of the Person

One way that our attributions are biased is that we are often too quick to attribute the behavior of other people to something personal about them rather than to something about their situation. This is a classic example of the general human tendency of underestimating how important the social situation really is in determining behavior. This bias occurs in two ways. First, we are too likely to make strong personal attributions to account for the behavior that we observe others engaging in. That is, we are more likely to say “Leslie left a big tip, so she must be generous” than “Leslie left a big tip, but perhaps that was because she was trying to impress her friends.” Second, we also tend to make more personal attributions about the behavior of others (we tend to say “Leslie is a generous person”) than we do for ourselves (we tend to say “I am generous in some situations but not in others”). Let’s consider each of these biases (the fundamental attribution error and the actor-observer difference) in turn.

When we explain the behavior of others, we tend to overestimate the role of person factors and overlook the impact of situations. In fact, the tendency to do so is so common that it is known as the fundamental attribution error (correspondence bias).

In one demonstration of the fundamental attribution error, Linda Skitka and her colleagues (Skitka, Mullen, Griffin, Hutchinson, & Chamberlin, 2002) had participants read a brief story about a professor who had selected two student volunteers to come up in front of a class to participate in a trivia game. The students were described as having been randomly assigned to the role of a quizmaster or of a contestant by drawing straws. The quizmaster was asked to generate five questions from his idiosyncratic knowledge, with the stipulation that he knew the correct answer to all five questions.

Joe (the quizmaster) subsequently posed his questions to the other student (Stan, the contestant). For example, Joe asked, “What cowboy movie actor’s sidekick is Smiley Burnette?” Stan looked puzzled and finally replied, “I really don’t know. The only movie cowboy that pops to mind for me is John Wayne.” Joe asked four additional questions, and Stan was described as answering only one of the five questions correctly. After reading the story, the students were asked to indicate their impression of both Stan’s and Joe’s intelligence.

If you think about the setup here, you’ll notice that the professor has created a situation that can have a big influence on the outcomes. Joe, the quizmaster, has a huge advantage because he got to choose the questions. As a result, the questions are hard for the contestant to answer. But did the participants realize that the situation was the cause of the outcomes? They did not. Rather, the students rated Joe as significantly more intelligent than Stan. You can imagine that Joe just seemed to be really smart to the students; after all, he knew all the answers, whereas Stan knew only one of the five. But of course this is a mistake. The difference was not at all due to person factors but completely to the situation—Joe got to use his own personal store of esoteric knowledge to create the most difficult questions he could think of. The observers committed the fundamental attribution error and did not sufficiently take the quizmaster’s situational advantage into account.

The fundamental attribution error involves a bias in how easily and frequently we make personal versus situational attributions to others. Another, similar way that we overemphasize the power of the person is that we tend to make more personal attributions for the behavior of others than we do for ourselves and to make more situational attributions for our own behavior than for the behavior of others. This is known as the actor-observer difference (Nisbett, Caputo, Legant, & Marecek, 1973; Pronin, Lin, & Ross, 2002). When we are asked about the behavior of other people, we tend to quickly make trait attributions (“Oh, Sarah, she’s really shy”). On the other hand, when we think of ourselves, we are more likely to take the situation into account—we tend to say, “Well, I’m shy in my psychology discussion class, but with my baseball friends I’m not at all shy.” When our friend behaves in a helpful way, we naturally believe that she is a friendly person; when we behave in the same way, on the other hand, we realize that there may be a lot of other reasons why we did what we did.

You might be able to get a feel for the actor-observer difference by taking the following short quiz. First, think about a person you know—your mom, your roommate, or someone from one of your classes. Then, for each row, circle which of the three choices best describes his or her personality (for instance, is the person’s personality more energetic, relaxed, or does it depend on the situation?). Then answer the questions again, but this time about yourself.

| Row | Personality Trait | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Energetic | Relaxed | Depends on the situation |

| 2. | Skeptical | Trusting | Depends on the situation |

| 3. | Quiet | Talkative | Depends on the situation |

| 4. | Intense | Calm | Depends on the situation |

Richard Nisbett and his colleagues (Nisbett, Caputo, Legant, & Marecek, 1973) had college students complete exactly this task—they did it for themselves, for their best friend, for their father, and for the newscaster Walter Cronkite. As you can see in Table 4.4 “The Actor-Observer Difference”, the participants checked one of the two trait terms more often for other people than they did for themselves and checked off “depends on the situation” more frequently for themselves than they did for the other person—this is the actor-observer difference.

| Person | Trait Term | Depends on the Situation |

|---|---|---|

| Self | 11.92 | 8.08 |

| Best Friend | 14.21 | 5.79 |

| Father | 13.42 | 6.58 |

| Walter Cronkite | 15.08 | 4.92 |

Like the fundamental attribution error, the actor-observer difference reflects our tendency to overweight the personal explanations of the behavior of other people. However, a recent meta-analysis (Malle, 2006) has suggested that the actor-observer difference might not be as strong as the fundamental attribution error is and may only be likely to occur for some people. For example, there is some suggestive evidence the actor-observer difference is less likely for people we know better.

The tendency to overemphasize personal attributions seems to occur for several reasons. One reason is simply because other people are so salient in our social environments. When I look at you, I see you as my focus, and so I am likely to make personal attributions about you. It’s just easy because I am looking right at you. When I look at Leslie giving that big tip, I see her—and so I decide that it is she who caused the action. When I think of my own behavior, however, I do not see myself but am instead more focused on my situation. I realize that it is not only me but also the different situations that I am in that determine my behavior. I can remember the other times that I didn’t give a big tip, and so I conclude that my behavior is caused more by the situation than by my underlying personality. In fact, research has shown that we tend to make more personal attributions for the people we are directly observing in our environments than for other people who are part of the situation but who we are not directly watching (Taylor & Fiske, 1975).

A second reason for the tendency to make so many personal attributions is that they are simply easier to make than situational attributions. In fact, personal attributions seem to be made spontaneously, without any effort on our part, and even on the basis of only very limited behavior (Newman & Uleman, 1989; Uleman, Blader, & Todorov, 2005). Personal attributions just pop into mind before situational attributions do.

Third, personal attributions also dominate because we need to make them in order to understand a situation. That is, we cannot make either a personal attribution (e.g., “Leslie is generous”) or a situational attribution (“Leslie is trying to impress her friends”) until we have first identified the behavior as being a generous behavior (“Leaving that big tip was a generous thing to do”). So we end up starting with the personal attribution (“generous”) and only later try to correct or adjust our judgment (“Oh,” we think, “perhaps it really was the situation that caused her to do that”).

Adjusting our judgments generally takes more effort than making the original judgment does, and the adjustment is frequently not sufficient. We are more likely to commit the fundamental attribution error—quickly jumping to the conclusion that behavior is caused by underlying personality—when we are tired, distracted, or busy doing other things (Geeraert, Yzerbyt, Corneille, & Wigboldus, 2004; Gilbert, 1989; Trope & Alfieri, 1997).

I hope you might have noticed that there is an important moral about perceiving others that applies here: We should not be too quick to judge other people! It is easy to think that poor people are lazy, that people who harm someone else are mean, and that people who say something harsh are rude or unfriendly. But these attributions may frequently overemphasize the role of the person. This can sometimes result in overly harsh evaluations of people who don’t really deserve them—we tend to blame the victim, even for events that they can’t really control (Lerner, 1980). Sometimes people are lazy, mean, or rude, but they may also be the victims of situations. When you find yourself making strong personal attribution for the behaviors of others, your experience as a social psychologist should lead you to stop and think more carefully: Would you want other people to make personal attributions for your behavior in the same situation, or would you prefer that they more fully consider the situation surrounding your behavior? Are you perhaps making the fundamental attribution error?

Self-Serving Attributions

You may recall that the process of making causal attributions is supposed to proceed in a careful, rational, and even scientific manner. But this assumption turns out to be, at least in part, untrue. Our attributions are sometimes biased by affect—particularly the fundamental desire to enhance the self. Although we would like to think that we are always rational and accurate in our attributions, we often tend to distort them to make us feel better. Self-serving attributions are attributions that help us meet our desires to see ourselves positively (Mezulis, Abramson, Hyde, & Hankin, 2004).

I have noticed that I sometimes make self-enhancing attributions. If my students do well on one of my exams, I make a personal attribution for their successes (“I am, after all, a great teacher!”). On the other hand, when my students do poorly on an exam, I tend to make a situational attribution—I blame them for their failure (“Why didn’t you guys study harder?”). You can see that this process is clearly not the type of scientific, rational, and careful process that attribution theory suggests I should be following. It’s unfair, although it does make me feel better about myself. If I were really acting like a scientist, however, I would determine ahead of time what causes good or poor exam scores and make the appropriate attribution regardless of the outcome.

You might have noticed yourself making self-serving attributions too. Perhaps you have blamed another driver for an accident that you were in or blamed your partner rather than yourself for a breakup. Or perhaps you have taken credit (internal) for your successes but blamed your failures on external causes. If these judgments were somewhat less than accurate, even though they did benefit you, then they are indeed self-serving.

Research Focus

How Our Attributions Can Influence Our School Performance

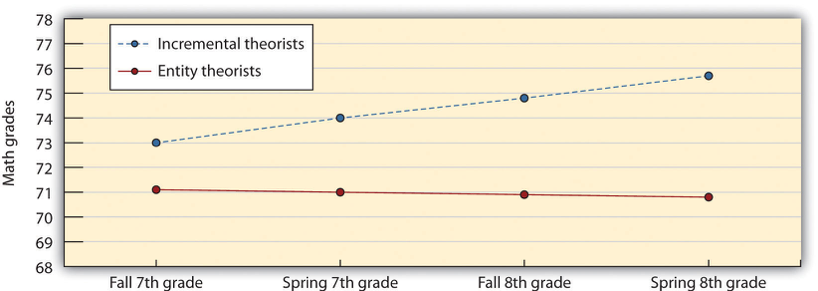

Carol Dweck and her colleagues (Blackwell, Trzesniewski, & Dweck, 2007) tested whether the type of attributions students make about their own characteristics might influence their school performance. They assessed the attributional tendencies and the math performance of 373 junior high school students at a public school in New York City. When they first entered seventh grade, the students all completed a measure of attributional styles. Those who tended to agree with statements such as “You have a certain amount of intelligence, and you really can’t do much to change it” were classified as fixed or entity theorists, whereas those who agreed more with statements such as “You can always greatly change how intelligent you are” were classified as growth or incremental theorists. Then the researchers measured the students’ math grades at the end of the fall and spring terms in seventh and eighth grades.

As you can see in int the following figure, the researchers found that the students who were classified as incremental theorists improved their math scores significantly more than did the entity students. It seems that the incremental theorists really believed that they could improve their skills and were then actually able to do it. These findings confirm that how we think about traits can have a substantial impact on our own behavior.

Attributional Styles and Mental Health

As we have seen in this chapter, how we make attributions about other people has a big influence on our reactions to them. But we also make attributions for our own behaviors. Social psychologists have discovered that there are important individual differences in the attributions that people make to the negative events that they experience and that these attributions can have a big influence on how they respond to them. The same negative event can create anxiety and depression in one individual but have virtually no effect on someone else. And still another person may see the negative event as a challenge to try even harder to overcome the difficulty (Blascovich & Mendes, 2000).

A major determinant of how we react to perceived threats is the attributions that we make to them. Attributional style refers to the type of attributions that we tend to make for the events that occur to us. These attributions can be to our own characteristics (internal) or to the situation (external), but attributions can also be made on other dimensions, including stable versus unstable, and global versus specific. Stable attributions are those that we think will be relatively permanent, whereas unstable attributions are expected to change over time. Global attributions are those that we feel apply broadly, whereas specific attributions are those causes that we see as more unique to specific events.

You may know some people who tend to make negative or pessimistic attributions to negative events that they experience—we say that these people have a negative attributional style. These people explain negative events by referring to their own internal, stable, and global qualities. People with negative attributional styles say things such as the following:

“I failed because I am no good” (an internal attribution).

“I always fail” (a stable attribution).

“I fail in everything” (a global attribution).

You might well imagine that the result of these negative attributional styles is a sense of hopelessness and despair (Metalsky, Joiner, Hardin, & Abramson, 1993). Indeed, Alloy, Abramson, and Francis (1999) found that college students who indicated that they had negative attributional styles when they first came to college were more likely than those who had a more positive style to experience an episode of depression within the next few months.

People who have extremely negative attributional styles, in which they continually make external, stable, and global attributions for their behavior, are said to be experiencing learned helplessness (Abramson, Seligman, & Teasdale, 1978; Seligman, 1975). Learned helplessness was first demonstrated in research that found that some dogs that were strapped into a harness and exposed to painful electric shocks became passive and gave up trying to escape from the shock, even in new situations in which the harness had been removed and escape was therefore possible. Similarly, some people who were exposed to bursts of noise later failed to stop the noise when they were actually able to do so. In short, learned helplessness is the tendency to make external, rather than internal, attributions for our behaviors. Those who experience learned helplessness do not feel that they have any control over their own outcomes and are more likely to have a variety of negative health outcomes (Henry, 2005; Peterson & Seligman, 1984).

Another type of attributional technique that people sometimes use to help them feel better about themselves is known as self-handicapping. Self-handicapping occurs when we make statements or engage in behaviors that help us create a convenient external attribution for potential failure. For instance, in research by Berglas and Jones (1978), participants first performed an intelligence test on which they did very well. It was then explained to them that the researchers were testing the effects of different drugs on performance and that they would be asked to take a similar but potentially more difficult intelligence test while they were under the influence of one of two different drugs.

The participants were then given a choice—they could take a pill that was supposed to facilitate performance on the intelligence task (making it easier for them to perform) or a pill that was supposed to inhibit performance on the intelligence task, thereby making the task harder to perform (no drugs were actually administered). Berglas found that men—but not women—engaged in self-handicapping: They preferred to take the performance-inhibiting rather than the performance-enhancing drug, choosing the drug that provided a convenient external attribution for potential failure.

Although women may also self-handicap, particularly by indicating that they are unable to perform well due to stress or time constraints (Hirt, Deppe, & Gordon, 1991), men seem to do it more frequently. This is consistent with the general gender differences we have talked about in many places in this book—on average, men are more concerned about maintaining their self-esteem and social status in the eyes of themselves and others than are women.

You can see that there are some benefits (but also, of course, some costs) of self-handicapping. If we fail after we self-handicap, we simply blame the failure on the external factor. But if we succeed despite the handicap that we have created for ourselves, we can make clear internal attributions for our success. But engaging in behaviors that create self-handicapping can be costly because they make it harder for us to succeed. In fact, research has found that people who report that they self-handicap regularly show lower life satisfaction, less competence, poorer moods, less interest in their jobs, and even more substance abuse (Zuckerman & Tsai, 2005). Although self-handicapping would seem to be useful for insulating our feelings from failure, it is not a good tack to take in the long run.

Fortunately, not all people have such negative attributional styles. In fact, most people tend to have more positive ones—styles that are related to high positive self-esteem and a tendency to explain the negative events they experience by referring to external, unstable, and specific qualities. Thus people with positive attributional styles are likely to say things such as the following:

“I failed because the task is very difficult” (an external attribution).

“I will do better next time” (an unstable attribution).

“I failed in this domain, but I’m good in other things” (a specific attribution).

In sum, we can say that people who make more positive attributions toward the negative events that they experience will persist longer at tasks and that this persistence can help them. But there are limits to the effectiveness of these strategies. We cannot control everything, and trying to do so can be stressful. We can change some things but not others; thus sometimes the important thing is to know when it’s better to give up, stop worrying, and just let things happen. Having a positive outlook is healthy, but we cannot be unrealistic about what we can and cannot do. Unrealistic optimism is the tendency to be overly positive about the likelihood that negative things will occur to us and that we will be able to effectively cope with them if they do. When we are too optimistic, we may set ourselves up for failure and depression when things do not work out as we had hoped (Weinstein & Klein, 1996). We may think that we are immune to the potential negative outcomes of driving while intoxicated or practicing unsafe sex, but these optimistic beliefs are not healthy. Fortunately, most people have a reasonable balance between optimism and realism (Taylor & Armor, 1996). They tend to set goals that they believe they can attain, and they regularly make some progress toward reaching them. Research has found that setting reasonable goals and feeling that we are moving toward them makes us happy, even if we may not in fact attain the goals themselves (Lawrence, Carver, & Scheier, 2002).

Adapted from “Chapter 6.2: Initial Impression Formation” and “Chapter: 6.3 Individual and Cultural Differences in Person Perception” of Principles of Social Psychology, 2015, used according to creative commons CC BY-NC-SA 4.0